Arts & Culture

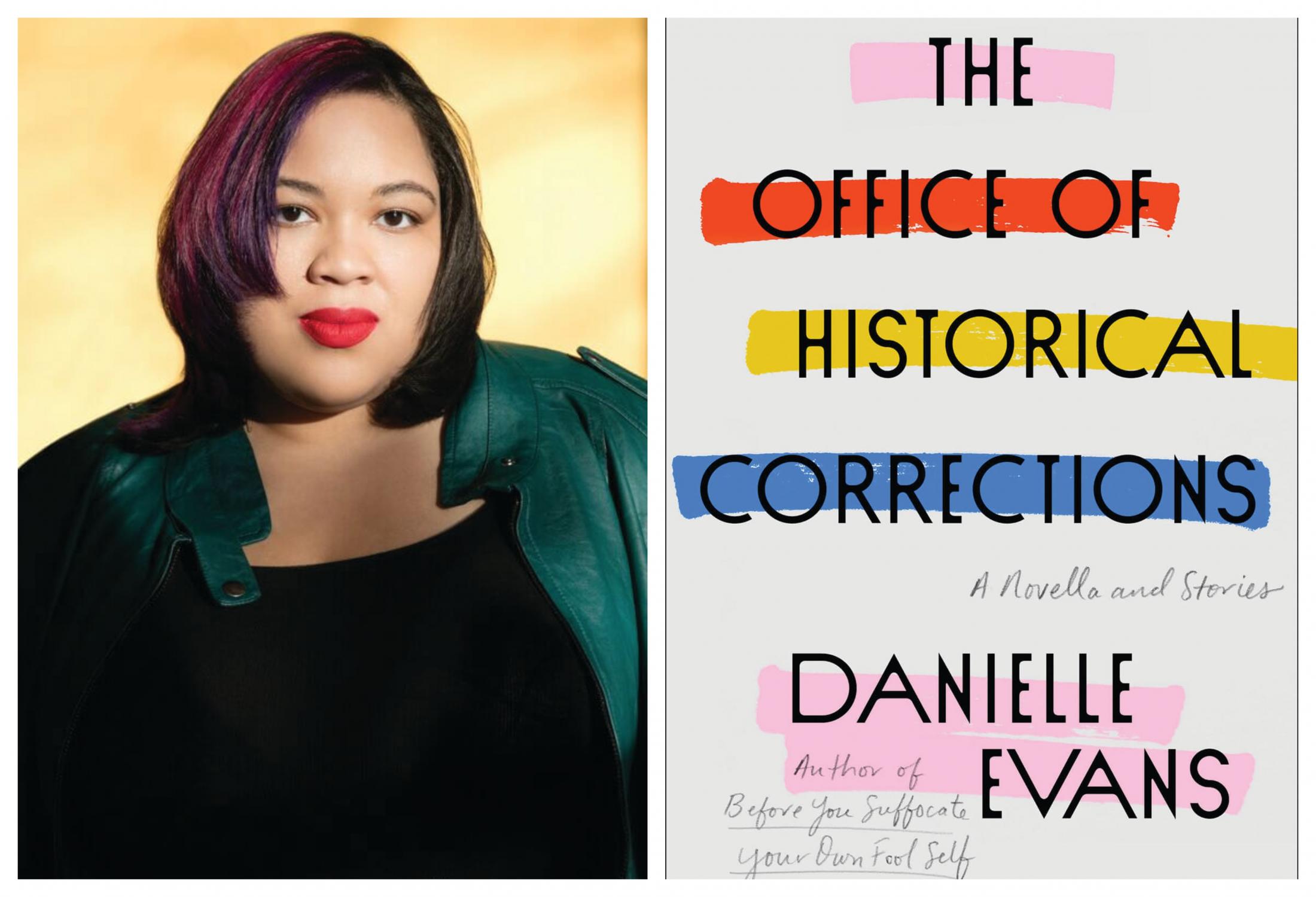

Danielle Evans Discusses Her Acclaimed Collection of Smart, Unpredictable Tales

'The Office of Historical Corrections' is informed, exquisite writing that demands to be read.

Danielle Evans was born in 1983 in Alexandria, Virginia, which means she is old enough to appreciate what the integration of the federal government—and the middle-class jobs that came with it—meant for Black families.

It also means the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars instructor is young enough to appreciate the surreal nature of a highway named after Jefferson Davis mere miles from the nation’s capital. Evans lived in several states growing up as she pursued her academic, teaching, and writing careers—all of which informs the short stories in her acclaimed recent collection, The Office of Historical Corrections.

These smart, intimate, unpredictable tales of mostly young Black women seem at once ahead of their time, as if looking back on current moment of racial reckoning, yet plausible enough that they could be headlines in tomorrow’s newspapers. The book’s informed, exquisite writing, however, demands to be read today.

We’re curious where your story ideas come from. A federal agency named The Office of Historical Corrections, which is both the title of the last story and the book, feels like it could almost exist.

Often for me, something goes from random idea to story when I can find a connection between two things that don’t feel connected. Strange things happen in the world all the time, so part of being a writer is just being observant. In the beforetime [pre-COVID], I took a lot of public transit, and I got a lot of my strange ideas—what just happened?—on public transit. The original spark for the novella came years ago when I was on the Metro in D.C. I was overhearing people having a wildly wrong conversation about a historical event.

The ramifications of history, both personal and political, inevitably impact the characters.

Often the story for me is in these strange intersections. The long-term questions I’ve been asking myself are about history, about responsibility, about agency, privilege, and fundamentally how privilege operates. I do think part of the project of this book for me, I realized about halfway through, is how a narrative changes if you just choose differently who the protagonist is. That’s true in a sometimes very personal way. It’s also true in the story we tell about the country or the story of history. If white Americans are the protagonists of the American story, then yeah, maybe we have hundreds of years of building better white Americans.

Other stories are very timely, especially “Boys Go to Jupiter,” which is about youthful transgressions, unintended and otherwise, racism, social media, and grief.

So I’ve been writing about the strangeness of diverse or multicultural spaces that are invested in this iconography for a really long time. In fact, originally, I thought that story was going to be a novel, based on a controversy that happened at a college in the 1990s that brought about a huge public debate. But I think part of what makes that story feel topical is social media. I am interested in social media and interested in social media as a story question because so much [today] is about who we understand ourselves to be and the difference between our public lives and private lives.