When Barry Levinson’s Diner was first released in 1982, it was a hit with audiences and critics alike. Famously, The New Yorker critic Pauline Kael was an early champion of the film, calling it “that rare autobiographical movie that is made by someone who knows how to get the texture right.” Roger Ebert gave it 3.5 out of 4 stars and compared it to classics like American Graffiti and Fellini’s I Vitelloni. (This was all the more extraordinary as it was Levinson’s first film.)

It was nominated for Best Original Screenplay at the Academy Awards. And it launched the careers of a host of young actors, including Mickey Rourke, Kevin Bacon, Ellen Barkin, and Steve Guttenberg.

In 2012, on the occasion of the film’s 30th anniversary, Vanity Fair wrote an article crediting Diner for creating an entire genre of comedy—the hangout comedy, where a group of people, often young men, sit around cracking wise, boasting (read: lying) about their sexual prowess, and passing the time. That genre was popularized in shows like Seinfeld and Friends and seen in the films of Quentin Tarantino (although in his case, the jocular patter is usually interrupted by a sudden spray of bullets). In 2006, it landed on AFI’s list of “100 Years…100 Laughs,” at No. 57.

But something I’ve noticed lately: People don’t talk about Diner as much as they used to. When British film publication Sight and Sound came out with its once-a-decade “Greatest Films of All Time” list in 2022, it didn’t make the cut. Notably, John Waters’ Pink Flamingos did (it was No. 211). When Diner’s 40th anniversary rolled around in 2022, there was little fanfare, save an Entertainment Weekly online interview with Levinson and a few of the film’s stars.

Somehow, the film seems to be out of critical and popular favor, perhaps seen as passe, a relic of the 20th century.

With all that in mind, I rewatched Diner last night, for the first time in about 20 years and I’m going to skip right to the headline:

Diner: Still Great.

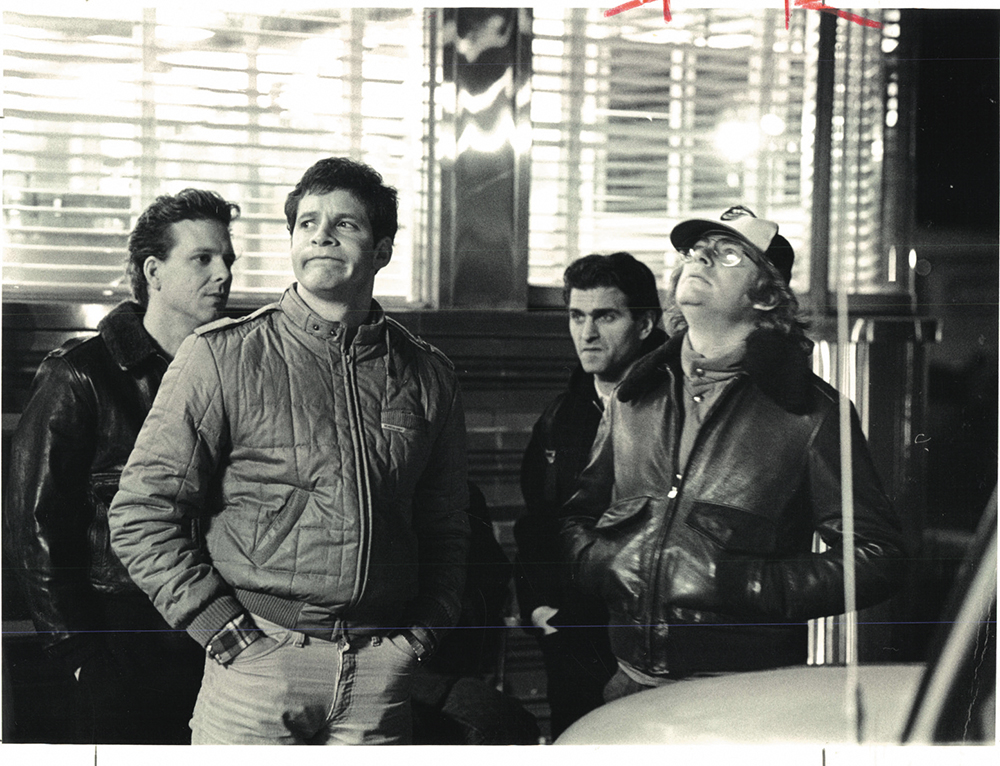

Just in case you’ve never seen it: Diner tells the story of six young men on the cusp of adulthood, mostly refusing to grow up, in 1959 Baltimore. Of the six, only Shrevie (Daniel Stern) is married, but he’s chafing against the restrictions of wedded life. Eddie is, reluctantly, engaged. They all hang out at the Fells Point Diner, depicted in all its chrome, vinyl, and jukebox glory by the since-closed Hollywood Diner on E. Saratoga Street.

It really is a remarkable film—beautifully shot and lovingly constructed, with a palpable sense of place that doesn’t feel show-offy. (Because Levinson is from Baltimore, he presents the city with relaxed familiarity, without needing to signpost its landmarks—although keen observers will spot many of them, including the American Can Company, Little Tavern hamburgers, and the Roland Park Presbyterian Church.) The dialogue, some of which was improvised, is fresh, loose, and funny—Levinson and his cast have a remarkable ear for the rapid-fire way young men actually talk. And his insights are trenchant: Levinson documents how difficult it is for these young men to express their feelings, how they substitute the cataloguing of stuff for actual emotional connection.

So Eddie (Steve Guttenberg) obsesses over the Colts and Shrevie can proudly rattle off the B-side to any single. (He’s frustrated when his wife, played with heartbreaking yearning by Ellen Barkin, doesn’t care about the intricacies of his record collection.) They all love the movies—they have film posters hanging on their walls. One minor character runs around quoting lines of dialogue from The Sweet Smell of Success. Eddie and Modell (Paul Reiser) argue over who’s a better singer, Frank Sinatra or Johnny Mathis. (“Presley,” weighs in Mickey Rourke’s Boogie, with the sly half-grin that launched his career as a bad-boy heartthrob.) Then they argue about whether or not the argument is dumb.

The film is loaded with memorable bits that have been oft imitated. There’s a scene where the brilliant but troubled Fenwick (a baby-faced Bacon) correctly shouts the answers to The College Bowl on TV, giving the raspberry and calling the contestants “bozos” when they answer incorrectly. There’s the famous “you gonna eat that?” scene, where Paul Reiser’s Modell can’t bring himself to simply ask for half of Eddie’s sandwich. (Similarly, instead of asking for a ride home, he sheepishly sidles up to Eddie and says: “You goin’ straight home?”) Eddie’s annoyance with Modell mirrors every time Jerry was irked by George or Kramer. Hell, even Justin Timberlake and Andy Samberg’s infamous “Dick in a Box” song was cribbed from Diner.

And it’s here where we get into what I suspect is the primary reason for Diner’s slight fall from favor: Its depiction of women is seriously outmoded. The women in the film have no agency. Eddie’s bride-to-be, Elyse, the one notoriously forced to take a 140-question Colts quiz before Eddie agrees to marry her, is never shown. We hear her voice, through a wall, tremulously answering arcane football trivia, and later see her back as she tosses her bouquet into the crowd (it lands on the stag table where the boys stare at it, stupefied). Other women are reduced to sexual objects. At one point, Fenwick “sells” his date to a friend for $5. The film would not pass the Bechdel test, not even close.

Of course, it’s important to make a distinction between depiction and endorsement. Diner is very explicitly about the fact that these guys are afraid of growing up—and women come to represent one of two things to them: an object of lust to be chased or a potential wife, i.e., a jail sentence to be avoided at all costs. (They view Shrevie as a bit of a cautionary tale, even though he seems to hang out with the boys as much as ever.) They cling to each other, to the diner of their teen years, to their jokes and their games and their banter, as a way to fend off the inevitable.

Indeed, this is exactly as these aging adolescents would have acted in 1959. And although today we would say that Boogie putting his dick in a box (of popcorn in this case) so that his date would inadvertently cop a feel is a kind of sexual assault, they wouldn’t have perceived it that way. “Ewww!” the victim of his prank says, running away—but later, she agrees to go out with him again.

I have no patience for the phrase “They couldn’t make this film today.” Of course, they couldn’t! Norms change. Sensibilities change. You need to put films like this in their proper historical and cultural context and stop judging old films by modern-day standards—it’s a recipe for missing out on a lot of great art.

Still, to watch this scene with fresh 21st-century eyes is admittedly tough. And I understand that not everyone is able to turn off their contemporary values and enjoy art for art’s sake. So some might be triggered or flat-out offended by the popcorn box scene and others might wonder why Elyse is never given a face. (I believe Levinson was making a point about the solipsistic nature of the friendship of these young men but still—harsh) The “selling” of Fenwick’s girl is a throwaway joke, as is a scene where the boys watch in awe as an overweight man attempts to consume the entire menu of the Fells Point Diner—essentially a fat joke that was as unfunny then as it is today.

Admittedly, there are tiny attempts to flesh out the female characters here—Billy (Tim Daly) has a girlfriend who wants to focus on her career, not him. (An unwanted pregnancy puts a crimp in her plans.) And Barkin’s Beth is lonely in her marriage and confused by why Shrevie’s precious record collection is so important to him. She comes on to Boogie, seeking the kind of male validation she got before she was married, which is sadly how she measures her own worth. (Notably, it’s Boogie, not Beth, who stops things from going too far.)

There was a time when making a movie strictly about the interior lives of young men was not just acceptable—it was expected. Then society noticed that there were way too many films like that—and very few similar depictions of women, POC, members of the LGBTQ community, etc.—and there was a bit a backlash. Sometimes, the backlash is needed to move the cultural needle—and it has worked. We’re seeing a much more diverse landscape of films, and the filmgoing experience is all the better for it (even if we still have a ways to go).

Still, I think it’s time to forgive Diner for being a product of its time and embrace it as the coming-of-age masterpiece it truly is.