Arts & Culture

Dead Poet’s Society

Edgar Allan Poe continues to entertain and inspire Baltimoreans from beyond the grave.

On a dark and still afternoon in October 1849, five people stood watch as a simple mahogany coffin containing one of the world’s most prolific authors was lowered into an unmarked patch of dirt in the heart of downtown Baltimore.

With clouds hanging low in the autumn sky, the small crowd—a former classmate, schoolmaster, and three relatives—paused for only a few minutes in the freshly turned earth, with the reverend, who was also the deceased’s cousin, electing not to deliver his prepared sermon to so few people.

Without pomp, circumstance, or even a tombstone to mark Edgar Allan Poe’s death, the group quietly dispersed, leaving the 40-year-old poet buried in Lot 27 of the Westminster Burial Ground with his grandparents, older brother, and the mysterious truth of his death.

Poe only lived in Baltimore for a few years, but the city shaped many aspects of his life, as well as its tragic ending. While he was born in Boston in January 1809 and raised by a foster family in Richmond, Virginia, this city is where he found the familial connections that would become the backbone of his life and career.

Between his unsuccessful stints in the Army and at West Point, Poe spent a few months in 1829 sharing a room with his cousin at the Beltzhoover’s Hotel on the corner of Hanover and Baltimore streets. He became a regular at The Assembly Rooms & Library on Holliday and Fayette streets, participated in a verse-writing challenge at the Seven Stars Tavern on Water Street downtown, and published 250 copies of his second book, Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems.

After he was dismissed from West Point on charges of gross negligence and disobedience in 1831, Poe took refuge in the city, too, moving into his Aunt Maria’s already-crowded household near Fells Point, sharing the small residence with his cousins and grandmother. The following year, when the family moved west to North Amity Street, Poe went with them, settling into their side of the rented duplex that still stands today.

Although the home has been renovated since Poe lived there in the 1830s, the integrity of its five rooms, as well as the original winding staircases, have remained intact. Enrica Jang, director of Poe Baltimore, the organization that maintains The Edgar Allan Poe House & Museum, says that most of the Poe House’s 13,000 annual visitors are struck by how the family fit so many people in such tight quarters. “The house is so small, and the argument could be made that he didn’t live here for very long,” Jang says. “But if you understand the history of what he created while he lived here, it’s huge.”

“But he found something that, I believe, he really wanted here in Baltimore—and that’s a family.”

After years of limited literary success, Baltimore became the site of a new beginning for Poe—one that shaped his career as a literary critic, editor, and author. Despite his overwhelming debts, he continued to write poems, some of which, including “Enigma [On Shakespeare]” and “Serenade,” were published in the Baltimore Saturday Visiter, and he labored over short stories, with a few published in The Philadelphia Saturday Courier.

He spent four years here working on his fiction and learning to shape his most grotesque ideas into narrative form. But his big break arrived in October 1833, when a few short stories from his collection titled The Tales of the Folio Club won a contest in the Visiter—considered his first true success. “Poe turned to short-story writing while he was here because he realized he could make money at it,” Jang says.

By the time Poe moved to Richmond in 1835 to join the staff of the Southern Literary Messenger, he had written at least 16 stories and a handful of poems. But within a few short months, Poe felt himself drawn back to Baltimore. His grandmother died that summer, leaving him dreadfully depressed, though the true root of his unhappiness was revealed in a letter about his cousin, Virginia. Dated August 29, 1835, Poe professed his love and potential as a future husband.

Today, stored deep in the belly of the Enoch Pratt Central Library, the original “proposal letter,” now nearly two centuries old, is one of the highlights of the institution’s impressive Edgar Allan Poe collection. Special collections manager Michael Johnson can quote a few phrases from the illustrious letter—My love, my own sweetest Sissy, my darling little wifey, think well before you break the heart of your cousin, Eddy. “He wrote stories in Philadelphia, New York, and Richmond, and had jobs all up and down the East Coast,” Johnson says. “But he found something that, I believe, he really wanted here in Baltimore—and that’s a family.”

After quietly marrying Virginia, who was 13 years old, in September 1835, Poe, then 26, only returned to Baltimore a handful of times before that fateful day in October 1849.

While there’s endless speculation surrounding the circumstances of his death, it is known that he had been traveling home from New York in the days before he was found lying semi-conscious outside of “4th Ward Polls,” a tavern at Gunner’s Hall on East Lombard Street. (Although The Horse You Came In On Saloon in Fells Point claims it was the last destination Poe visited, there isn’t any evidence that he actually imbibed there.)

It was assumed Poe was drunk, and so he was put in a carriage and sent to a hospital a few blocks south of where Johns Hopkins Hospital now stands. He was said to look “repulsive,” according to the acquiantance who found him, with messy hair, a dirty face, and “lusterless and vacant” eyes. Poe never regained enough coherence to explain how he had come to the condition in which he was found, and he died four days later.

Poe’s shadowy death can only be described using his own writing, as author Arthur Hobson Quinn wrote in his Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography: “The ‘fever called living was conquered at last,’ and the poet who had seen farthest into the dim region ‘out of space, out of time’ went on his last journey, alone.”

But in a sense, Poe hasn’t been alone since. What started as a slow build of local appreciation for the literary figure—bolstered by Baltimore teacher Sara Sigourney Rice’s efforts to erect a memorial at Poe’s burial place during the 1870s—has grown rapidly as details about his life, work, and death reached all corners of the country.

During the early 1900s, cities where Poe had spent significant time—Richmond, New York, Boston—began to lay claim to their portions of his past. Baltimore was among the first to begin adopting him as one of its own, mounting a statue of the author in the Gordon Plaza of the University of Baltimore in 1921 and creating the Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore in 1923.

Jeffrey Savoye, current secretary and treasurer of the local Poe Society, joined the group in 1983, which was a few years after it turned over control of the Poe House to the city, and some 40 years after its members saved the structure from demolition. He started seriously studying Poe in college, and it was then that he began to see the poet as a misunderstood figure who, at one time, had been “abused in the public view” by his critics. “That not only reawakened my interest, but it became a kind of cause for me—I felt as if his reputation needed saving,” says Savoye, who has since published more than 45 Poe-related scholarly articles and established the Baltimore society’s website, a comprehensive reference guide about the author, as well as the largest collection of Poe’s writings in the world. “Poe has a way of reaching out from beyond the grave and inserting himself anywhere in modern times.”

As more people have read Poe’s most famous works, such as “The Raven” and “The Cask of Amontillado,” he has gained a posthumous following of fans who revere him for his revolutionary horror writing. Sometimes called the “grandfather of horror,” Poe was one of the first to write intentionally from the perspective of madness, while also threading complex themes of sorrow, humor, and agony throughout his complicated narratives, which were not completely unlike the trials and tribulations of his own life.

“If all you get from Poe’s work is the horror of it, you’re going to have a good time,” Jang says. “But when you read deeper into it, you see the humanity and much more primal emotions. Underneath the themes of horror and fear, there is clearly love and pain.”

As the decades went on and the fandom continued to grow, Baltimore and its various “Poe sites” became a destination for people looking to draw themselves closer to the author, especially after the city’s obsession went national in March 1996 with the announcement that its new football team would be named after the infamous bird in his most recognizable poem.

Today, people travel from near and far to take tours of the Poe House, look through the Central Library’s artifact collection, and pay their respects at his final resting place. “I’ve had people burst into tears or people’s hands start shaking when they see those pieces,” Johnson says of the library’s sliver of Poe’s original coffin and locks of his and Virginia’s hair. “It’s powerful to them because of how much they love Poe.”

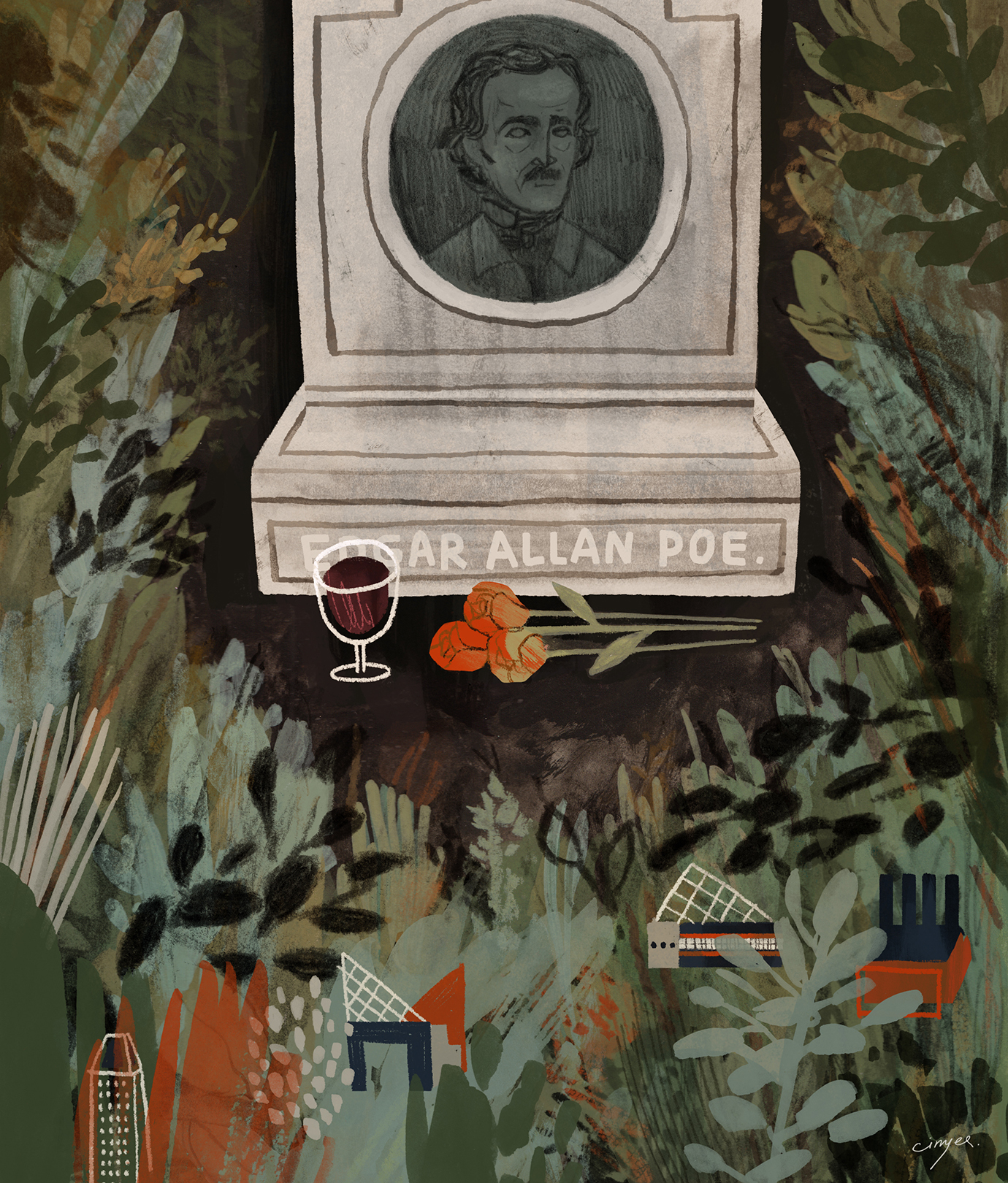

The locations themselves have even become the subjects of local folklore. From around 1949 to 2009, a mysterious person (or persons) wearing all black and a big hat would visit Poe’s grave in the wee hours of his birthday night, drink a glass of cognac, and leave three roses and the rest of the bottle on the memorial. The figure became known as the Poe Toaster, and while no one ever unmasked them, it became a tradition that drew a small group of onlookers every year. The ritual was halted after the author’s 200th birthday, but the Maryland Historical Society and other local organizations picked a new anonymous Poe Toaster to carry the torch starting in 2016.

It has been 170 years since Poe took his final breath here, but he and his work continue to spark creativity and connection in Baltimoreans. Kurt Bragunier, owner of the Poe-themed Annabel Lee Tavern, says he relates to the author’s artistic spirit, and so he adorned the walls of his Canton restaurant with murals and artworks dedicated to Poe’s likeness. For 12 years, casual fans and Poe fanatics alike have been able to flock here to debate his best poems over dinner, celebrate his birthday with black sheet cake, and, if they’re lucky, catch a glimpse of Bragunier’s original 1850 copy of the restaurant’s namesake poem. “I want this building to always be a monument to Poe, even after I’m gone and the restaurant is gone,” he says.

“I can’t think of any other city in the U.S. that reveres a writer the way that Baltimore reveres Poe.”

More recently, the Lord Baltimore Hotel began hosting a bi-monthly comedy show at Poe’s Magic Theatre, and there’s even a storytelling cruise around the Inner Harbor—aboard the Raven, no less—that discusses Poe’s presence in Baltimore. This August, the Baltimore-based National Edgar Allan Poe Theatre teamed up with local public radio station WYPR to premiere a part-radio drama, part-podcast series called Poe Theatre on the Air. Each month, co-founder Alex Zavistovich and a team of actors read adapted versions of some of Poe’s ghastly tales over the airwaves. “I think that giving people the opportunity to experience Poe beyond the limitations of the page is extremely valuable,” Zavistovich says. “When you hear it recounted, your mind fills in the blanks that reading it might not give you.”

But Baltimore’s latest claim to fame is the International Edgar Allan Poe Festival & Awards, which was created last year to bring fans from across the world together for a two-day celebration of his “death weekend.” It’s the first time that representatives from other historically significant Poe cities, including The Poe Museum of Richmond and the Bronx County Historical Society, which runs Poe Cottage, have joined forces with Poe Baltimore to give the festival’s thousands of attendees a well-rounded look at his life.

As Baltimore is the host city, many of the festival’s activities emphasize his time here, and for good reason. “Baltimore has the body, so I think we’re at the top of the list,” Jang says with a laugh. “But I like that all of the Poe places can celebrate and enjoy the history with each other.”

This year, in fact, 170 since his death, Poe’s dismal burial scene will happen again, but this time, mourners will travel by the busload to attend his “funeral” reenactment at the Carroll Mansion on Lombard Street—complete with a historically accurate casket, a hand-sculpted head, and a “body” dressed in a Christopher Schafer suit. Not to mention the dozens of wakes, readings, and performances being held across the city in his honor, while the Poe Society of Baltimore will also host its 97th commemorative lecture presented by a scholar who has dedicated their life to studying him.

Although some people might think it’s strange that places such as his grave and the North Amity Street home—now surrounded by both public housing and luxury apartments—have become shrine-like destinations for thousands of visitors every year, it’s a point of pride for local Poe fans. He may have struggled during his years here, but he worked through his hardships to achieve the type of success he always wanted.

“I can’t think of any other city in the U.S. that reveres a writer the same way that Baltimore reveres Poe—he’s not just a writer; he’s a feeling, an ethos, and it’s tied up in the identity of the city,” says Jang. “Poe suffered, but he was also highly intelligent, very sharp, and funny. I think that if you ask people who live in Baltimore, they would make the same observations about the city. There’s a true identification, I think, that great things can come from humble places.”