For decades, Ernest Shaw’s large-scale murals and mixed media portraits have been integral landmarks in Baltimore City. In 2017, Shaw was awarded the Ruby’s Artist Grant for Visual Art. The artist used those earnings to curate a series of community dialogs that interrogated stereotypes and presumptions about black masculinity.

Those conversations informed two large bodies of work: a series of mixed media works on canvas of historic African American cultural and political figures, and a collection of graphite works on paper that feature portraits of women who have experienced abuse or sexual violence. Selections from both of those series will be on view in the exhibition TESTIFY! A Life’s Time of Emerging Blackness, which debuts July 11 and runs at the Motor House gallery in Station North through September.

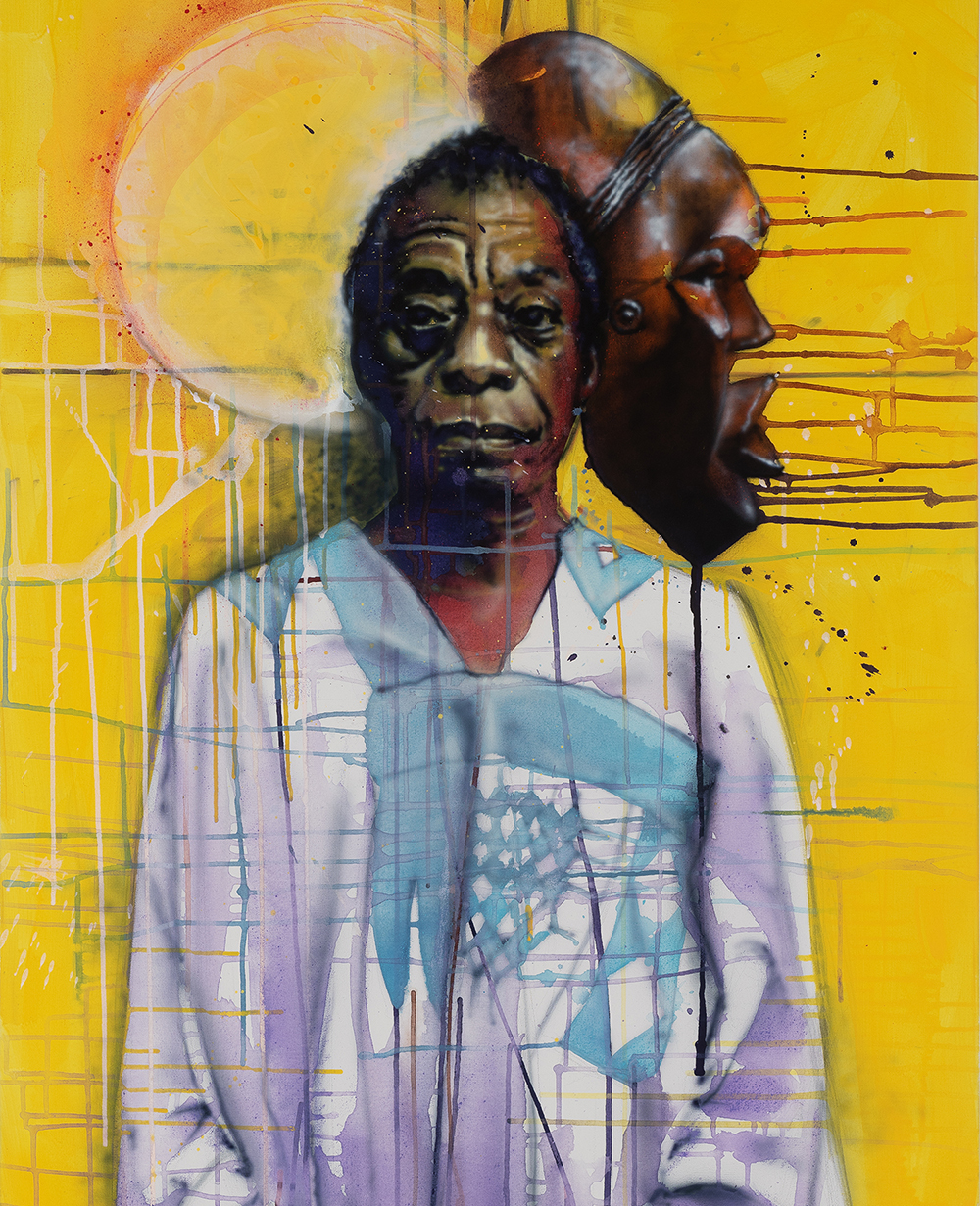

Inspired by Carvaggio’s use of light and shadow, as well as Dunbar and DuBois’ theories about the duality of black identity, Shaw immortalizes prominent thought leaders, creatives, and historic figures. Among them are James Baldwin, Nina Simone, Wole Soyinka, Thelonius Monk, George Stinney Jr., and Okwui Enwezor—along with others whose work and walk have indelibly transformed the world.

“The history of this country should be illustrated not just told.” Shaw shared during our studio visit. “I want people to ask questions. I want people to experience the work and to be activated by whatever they bring to the work.”

Shaw’s style is unmistakable. The portraits he renders employ rhythmic gestural marks and stand as polyphonic mixed media compositions that are as free and eloquent as jazz itself. His portraits riff on realist and surreal adaptations of mythic figures—outliers whose likenesses have been reproduced countless times. Sometimes, a reproduction can flatten rather than elevate a legacy.

Some artists crumble under the pressure to visualize lifelike depictions of cultural giants. How do you capture Monk’s moody-blue brilliance or realize the celestial countenance of Sun Ra in a two-dimensional painting? How can you encompass the cutting wit of Baldwin’s scholarship or the brooding radicality of Simone’s timeless anthems in a singular portrait? Shaw culls a history of transformative black creative genius to found new monuments that declaratively refuse to be forgotten.

The iconography that Shaw incorporates in his portraits draw from traditional African Diasporic spiritual systems that have been invoked to heal, transmute, and transcend our corporeal forms. Loosely sketched and realistically detailed renderings of Yoruba masquerades, Dogon symbols, and Guinea Monkey Masks, hover like protective apparitions behind and around his subjects. The masks serve as a tether that binds the 19th, 20th, and 21st century figures to precolonial African narratives.

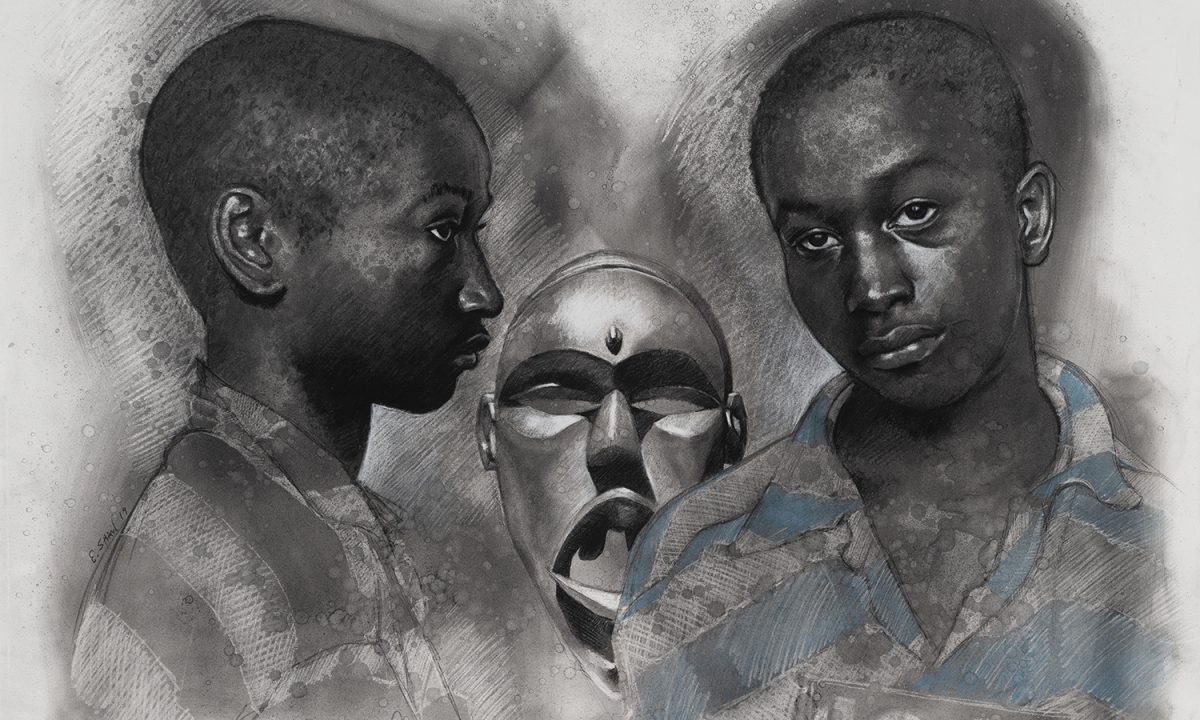

In George Stinney Jr., (2019), a charcoal work on paper, Shaw renders a realist profile and front facing mugshot of fourteen-year-old George Stinney Jr., the youngest person in American history to be executed by electric chair. Stinney was accused of murdering two white girls in Alcolu, South Carolina in 1944. Though Stinney was convicted in just ten minutes, evidence erected seventy years after his execution exonerated his death and acknowledged his wrongful conviction.

American history is rife with these kinds of horrific injustices. Black children are regularly prosecuted as adults. Biases in the criminal justice systems presume the criminality rather than the innocence of black men and women. Shaw’s inclusion of Stinney among portraits of entertainers and scholars is telling.

“I want folks to look at the portrait and learn more about the story of George Stinney,” Shaw noted. “I want them to become more aware about the works of someone like James Baldwin or Nina Simone.”

The portrait is tinged gray and blue. The expression on the boy’s face is solemn and haunting. Stinney is Freddie Gray and Tamir Rice, and the countless others who have been killed before technology could be leveraged to enforce accountability. Despite our advances, Stinney’s portrait stands as a troubling testament about a legacy of perpetual systemic violence and disregard for black life.

In contrast, St. James on the Cross (2019), a golden hued acrylic portrait of James Baldwin on canvas shows the regality, power and tenacity of black identity. Baldwin is draped in a long ivory tunic highlighted with indigo and light blue patterns. He stands affirmed and unabashedly confident against a bright yellow background. His eyes directly confront our gaze. His poise demands our respect. A wooden sculpture hovers in profile over his left shoulder. A dripping sun rises above his right. Baldwin’s portrait is a stunning testament to a long tradition of creative genius.

The power of the images Shaw produces resides in the narratives he encourages us to consider. I asked him what he hoped viewers of the exhibition would walk away with. His answer was precise and direct, “Black folks are human.”

TESTIFY!, not only acknowledges an awe inspiring cadre of dynamic lives, it also emboldens us, the viewers, to reflect on the influence and impact of our collective history.

“If you can’t see the humanity in George Stinney’s life, Baldwins words, or Simone’s songs, then there are some things you need to work on,” Shaw says. “My engagement with the audience is to exhibit the humanity of melanated people. To hold up the mirror to other melanated people to say ‘I am beautiful, I have a story, a history, a culture, a language, a psychology, a cosmology, I am a part of that, I have all of that.’”