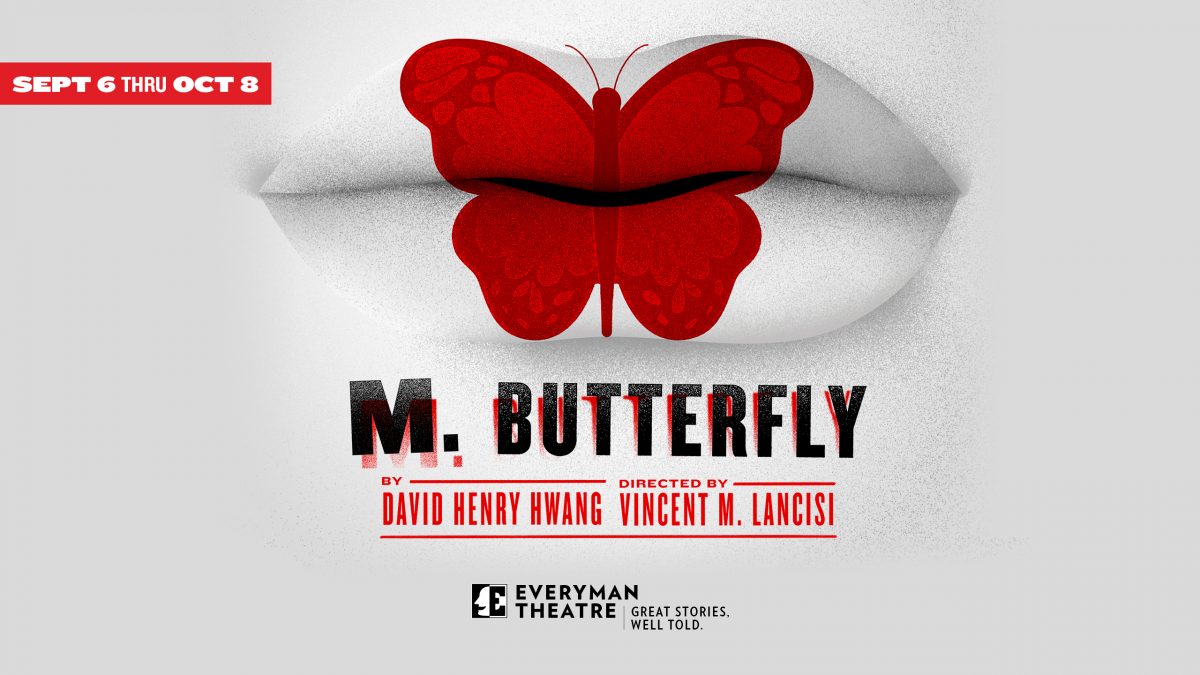

Everyman Theatre’s artistic director Vincent Lancisi and veteran company member Bruce Nelson got the rarest of opportunities this summer. A chance encounter led them to a meeting with the man who was the inspiration for the main character, Rene Gallimard, in the Tony Award-winning M. Butterfly, which opens Everyman’s season on September 6.

In the play, Gallimard, a French diplomat, is seduced by Chinese opera singer, who turns about to be masquerading as a man. The two are swept up in a tale of espionage, hidden identities, and betrayal. Nelson, who plays Gallimard, joined us to talk about what happens when you meet the real-life inspiration for your character.

This story seems like you couldn’t make it up if you tried. How did all of this happen?

One day, I was passing by Vinny’s office, and he told me to come in and sit down, that he had a story for me. This crazy coincidence begins to unfold, where Vinny’s wife had opened up to the driver of a tour bus in France and that tour guide had told them that he was the private driver for a famous guy, that there was a movie and a play about. Vinny’s ears perk up immediately, and the driver can’t believe he knows that it’s M. Butterfly. They get the man, Bernard Boursicot, on the phone, and they arrange for a visit. The only sticking point was it seemed too good to be true. We all decided to take a leap of faith, and these donors stepped forward to make the trip possible. Maybe two weeks later, I was on a plane to Paris.

It seems like you never get these kinds of opportunities as an actor.

Yes. You assume for the better part of your career you’re not going to know anything about the person you’re playing except for what you’ve made up. It was thrilling to be able to layer on my experience with Bernard. I had developed in my mind that he was a bigger-than-life personality. Somehow, I’d gotten into my mind that, as a former diplomat, he was living in a fabulous chateau in the French countryside where he was waited on by white-gloved waiters. And we would be swept in, wined and dined, told this fabulous story—and maybe we would get a scoop, there would be something we’d learn that nobody knew.

But then we showed up at a nursing home, and he was this 74-year-old man—and old for 74—with too much hair and needing a shave, wearing clothes that maybe he’d worn a couple of days in a row. And he lived in a little cell of a room—like the jail cell where his character is at the beginning of the play. He is diminished, he is small, and he is real—not larger-than-life. There might have been a part of me that thought, ‘I don’t want to know this.’ The Bernard in my mind is very different from this. He did seem to give credence to the fact that as a twenty-something, going on this very wild adventure, he was naïve and he was easily taken advantage of. And he kept saying ‘yes’ to wild opportunities that he had no business saying yes to, but that informed the next several steps in his past. The idea that he was open to being duped I think made the duping possible. It does make for an amazing, epic story.

What was the visit like?

He was waiting outside in the rain for us under a little awning. It was like out of a movie. There was rain on the windshield, and we could see him waiting, and we were like, that’s Bernard? We get out and he takes us into the wing where he lives. It had glaring fluorescent lights, and there weren’t enough seats for us, so we kind of perched on his bed.

In the book, when Bernard needed money, he would sell off some item that he’d collected in his adventures. His room was spare and Spartan. There was one little album that he flipped through and showed us some things. And he did present us, wonderfully, charmingly, with two ties. The visit was about four hours. At one point, we had this wonderful meal, a four-course dinner catered by the nursing home’s kitchen—wine, cognac, lovely dessert. He ate like a horse, and the actor, the psych 101 in me, wondered what he was really hungry for—has he got enough in life? So it was just eating, chitchatting, and then we were on the road, dumbfounded that it had happened.

How has that experienced informed the character for you?

He’s small now. We open the show, not on a bigger than life, grand scale type guy. He is a simple, real man. And it’s sad that he couldn’t be fully who he was. He was a gay man who can’t be a gay man. And I can get that you can’t be yourself, you have to hide. Even when all the evidence points to what you truly are, you deny, deny, deny.

He was a man clearly rooted in a certain way of being, and I guess the fight out of that was probably why it hit him so dreadfully hard that the opera singer was a man that he was able to deny that. That suggests wanting to save himself and that he’s an insecure person who needs to maintain the wall. Oh, it’s so sad. But when you go on stage, you can’t play the sad, you can’t play the pity, you’ve got to advocate for your character. And it’s the audience’s job to get drawn into the sadness.

So, during the visit, did you get your scoop?

There were no scoops. He continually recounted, in an almost formulaic way, what we already know from the book and the articles about the story. We didn’t expect that [during our visit] Bernard would continue to refer to the opera singer as ‘his majesty.’ There was an upper hand.

We want the story in a lot of ways to be a love story, and I think part of the power of the play is you are led to believe that they are falling in love, and then it’s something much, much more. It’s espionage, a man pretending to be a woman. You have to draw the audience in, believe that it’s a love story, and then you break that apart. You get the audience questioning and wondering.