Arts & Culture

Museum Ours

An inside look at the BMA's 100-year relationship to Baltimore.

FALL ARTS PREVIEW

An inside look at the evolution of the BMA’s 100-year relationship to Baltimore.

By John Lewis

The fall arts season is packed with exceptional events—check out our Editor’s Picks for proof—but The Baltimore Museum of Art’s 100th anniversary deserves particular attention. The museum was founded in 1914 with an eye toward bringing art to the community, and, basically, that mission hasn’t changed. But over the past century, notions of art and community have changed profoundly, and the BMA has adjusted—sometimes, ahead of the curve; other times, struggling to keep pace. Though its course may have been charted by a handful of determined directors and prescient curators and collectors, its evolving identity suggests something grander at work, something inextricably linked to the city’s history and how we view ourselves. In fact, the BMA’s legacy is as much about Baltimore as it is about art.

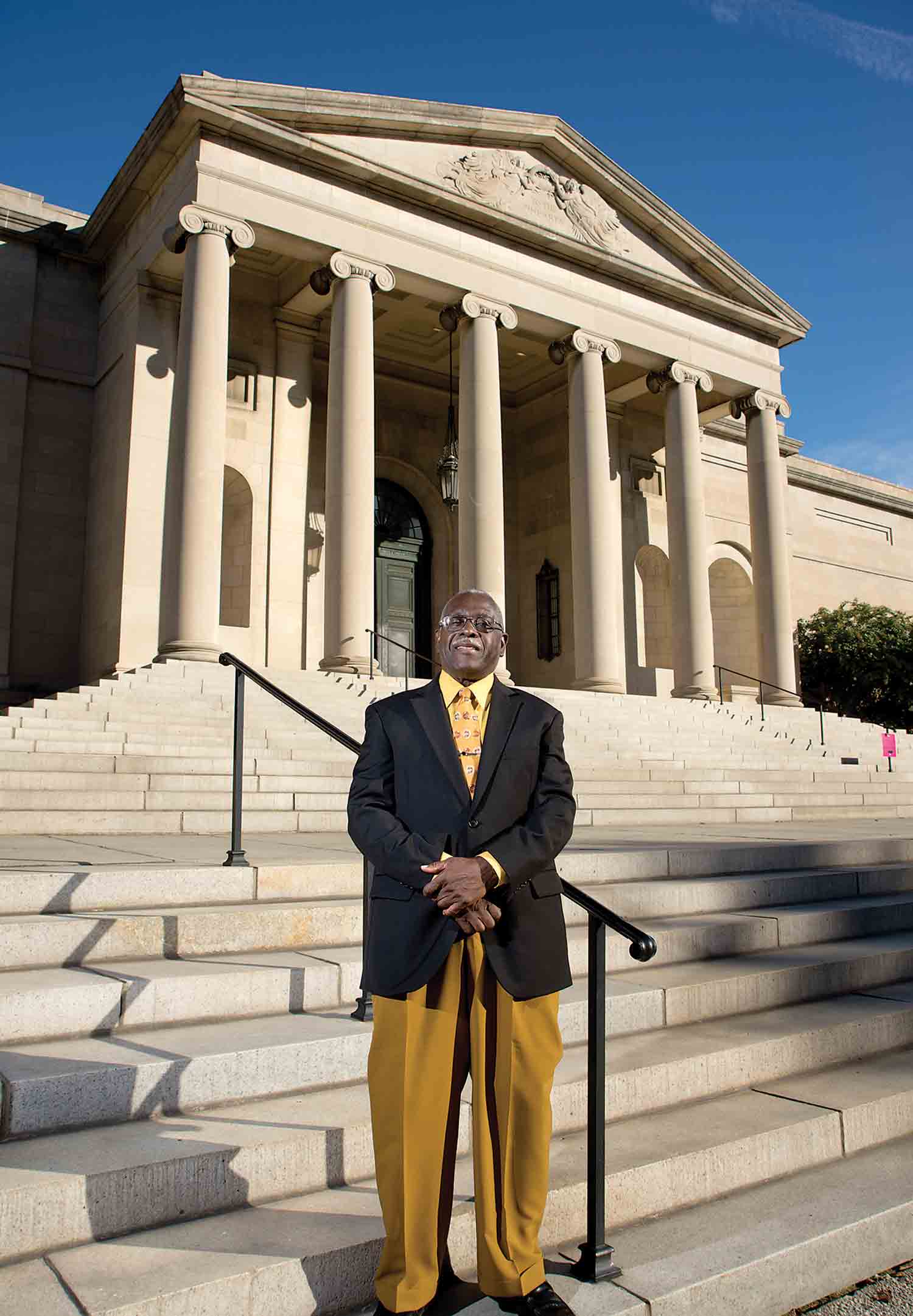

Carl Carver, standing in front of the BMA’s Grand Front Entance, which reopens in November. Photography by Mitro Hood.

The survey went out in the fall.

Part of an ambitious community-outreach initiative spearheaded by The Baltimore Museum of Art’s [BMA] board of trustees, it queried hundreds of local businesses, community leaders, stakeholders, and even the Boy Scouts about their relationship to the museum and what they wanted from it going forward.

It included questions like: How often have you visited? What appealed to you? Do you believe the museum should devote itself primarily to the work of living artists? Do you believe the museum should show more commercial art? What types of exhibitions would you like to see?

Responses came in from all over the city. A manufacturing company reported that roughly half its workers were interested in “nothing” related to the BMA, and the other half wanted to see exhibitions of firearms and old watches, along with photography and modern art; a local pharmacist suggested “celebration and exhibition by different nationalities residing in Baltimore;” and a graphic design group hoped the museum could be more “articulate” and less “static and stodgie [sic].”

The vice-principal of Booker T. Washington High School believed the museum should be more of a presence at area movie theaters, while a representative of the Archbishop of Baltimore urged the BMA to “provide poetry for the light of the moon” (whatever that means), and a member who wasn’t named John Waters said he’d like to see an exhibition of art in “bad taste.”

The range of responses shows the challenges faced by an institution trying to accommodate various constituencies and reach others, while simultaneously acknowledging its history and moving forward. It’s all the more poignant when you consider that this particular survey was conducted in 1937.

As the BMA marks its 100th anniversary this fall, connecting to the community has become paramount. “We’re always working to make the museum a place where everyone feels welcome,” says director Doreen Bolger, “so we keep changing all the time. As we do, we constantly circle back to the past, because everything is connected.”

Looking at that history, it’s striking how the museum barely resembles the repository of objects it used to be. In other ways, it hasn’t changed at all.

Anthony van Dyck’s 17th-century painting, Rinaldo and Armida, a piece Carver rehung “a few times” during his long stint at the BMA. Baltimore Museum of Art. BMA 1951.103.

Carl Carver witnessed more change than anyone. “Carl had his ear to the ground,” says Arnold Lehman, the museum’s director from 1979 to 1998, “and I always listened to what he had to say, because he often understood what was going on better than any of us.”

Brenda Richardson, former BMA deputy director, echoes those sentiments, calling Carver “one of the most exceptional human beings I’ve ever met. He played a key role at the museum for a very long time.”

Carver had no background in art before coming to the BMA. Originally from Elizabeth City, North Carolina, he had been a baker at Silber’s on Reisterstown Road and at Bond Bakery at North Avenue and Harford Road. He also worked for awhile at a body shop on Monument Street.

Sitting in the dining room of his Gwynn Oak row house, Carver, now 80, says his wife spotted a BMA help-wanted ad for “porters,” and he applied. He started on August 6, 1964, in the housekeeping department, making $78 every two weeks. “This was before integration,” recalls Carver, noting that there were few African-American employees at the time. “Mostly, we just cleaned, and that museum was dirty.”

Besides waxing floors and shoveling snow (sometimes off the roof), Carver also hung art. Trude Rosenthal and Mimi Powell—at the time, chief curator and director of installations, respectively—recruited him to set up exhibitions and taught him to hang paintings. “The most important thing was handling the object by the frame,” he says. “And, of course, the measurements were important, and I was always careful with things. I learned that skill during my days as a baker, when I had to put in just the right amount of ingredients.”

Powell, who was especially particular about presentation, would oversee the installation or leave detailed instructions with Carver. “She insisted that everything be perfect,” he recalls. “I’d have the paintings on the wall, and she might say, ‘Carl, this one should be a little to the left."

“People seem to feel that the Museum belongs to them and they are sincerely proud of it and its activities.”

At that point, Powell would check the measurement herself, using the hem of her apron. “She wore a work apron all the time,” says Carver, “and she’d hold up the end of it, look down, look at the painting, look down at that apron again, and announce, ‘It’s two inches off.’ Ninety-nine percent of the time, she’d be right, and I’d re-hang it.”

The added responsibility never bothered him; in fact, he appreciated the opportunity. “I eventually got pretty good at it,” he says, smiling. “I never had anything fall off the wall.”

He casually mentions re-hanging the Cone Collection three times and Rinaldo and Armida, Anthony van Dyck’s 17th-century masterpiece, “a few times.” When summer temperatures exceeded 90 degrees, he would take Old Master paintings off the Jacobs Wing walls and move them to the Cone Wing—for years, the only air-conditioned area in the museum—for safekeeping against the heat. Guards sometimes fainted in the stifling gallery.

When asked if he developed an affinity for any of the artwork, Carver pauses a few moments. “I was always fascinated by [Rodin’s sculpture] The Thinker,” he replies. “I’d stop and stare at it for minutes at a time. There’s something about that man sitting there like that. It made me think.”

He runs a hand over his gray hair: “Man, I moved that thing so many times. We eventually put it on wheels.”

Carver transferred to security, before becoming assistant building superintendent and facilities manager. He can tell you where the roof leaked, which director knew all the guards’ names, and which pieces were stolen over the years (surprisingly few for a collection of 90,000-plus objects). He can point out the vase that was toppled by an electrician’s cart and the abstract masterpiece that got stepped on and needed repair.

During his stint as a night watchman in the early-1970s, he says a fellow guard, spooked by co-workers’ ghost stories, brought in a German shepherd to accompany him while making rounds. “We had to let that guy go,” says Carver, who officially retired in 1997, but later returned to work as a security guard until 2012.

The museum’s relationship to the community changed profoundly during his tenure, he says, as it exhibited more work by African-American artists and, as a result, attracted more African-American visitors. “We also had more programs geared toward black people, even for parties,” notes Carver. “When I started, that was unheard of.”

The museum’s Kwanzaa celebrations, performances by groups like Sankofa Dance Theater, and the Joshua Johnson Council’s outreach to the African-American community also helped.

“Inside the museum, it finally started looking like the city outside,” says Carver.

Jay Fisher's Top 5

The longtime BMA curator selects the “non-Cone” pieces you shouldn’t miss.

The Game of Knucklebones

TELL ME MORE

The Baltimore Museum of Art was incorporated in 1914 by a group of eight citizens that included Henry Walters and Robert Garrett. According to a booklet published at the time of incorporation, the group felt Baltimore lagged behind other cities “in regard to matters of esthetic interest.”

A museum, they believed, would help remedy that: “[It] would not only give pleasure and inspiration to many, but it would raise standards of taste, encourage art, place models of esthetic quality before those interested in the industrial arts, and also increase the prestige of Baltimore as an American city.”

It started with one piece of art—a William Sergeant Kendall painting, Mischief, donated by Dr. A.R.L. Dohme. The founders were confident more would follow and arranged for the donated art to be stored at Peabody Institute until a building was obtained.

In 1923, the BMA found a temporary home at 101 W. Monument Street, the former residence of Mary Elizabeth Garrett. There, the museum presented paintings, sculpture, etchings, furniture, and metal-work exhibitions. Admission was free, and more than 25,000 people came to the museum in the first six months.

The BMA also appointed its first director, Florence Nightingale Levy, a former curator at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Levy surveyed fellow directors from New York to Houston, gathered critical information about operating costs and levels of city and state support, and established credibility that made the move to a permanent location all but inevitable.

Designed by John Russell Pope (who later designed the National Gallery of Art and the Jefferson Memorial) and constructed on land donated by The Johns Hopkins University, the neo-classical building opened in 1929. As predicted, it was something of a build-it-and-they-will-come scenario: donated art steadily trickled in, and it wasn’t long before the museum needed to expand.

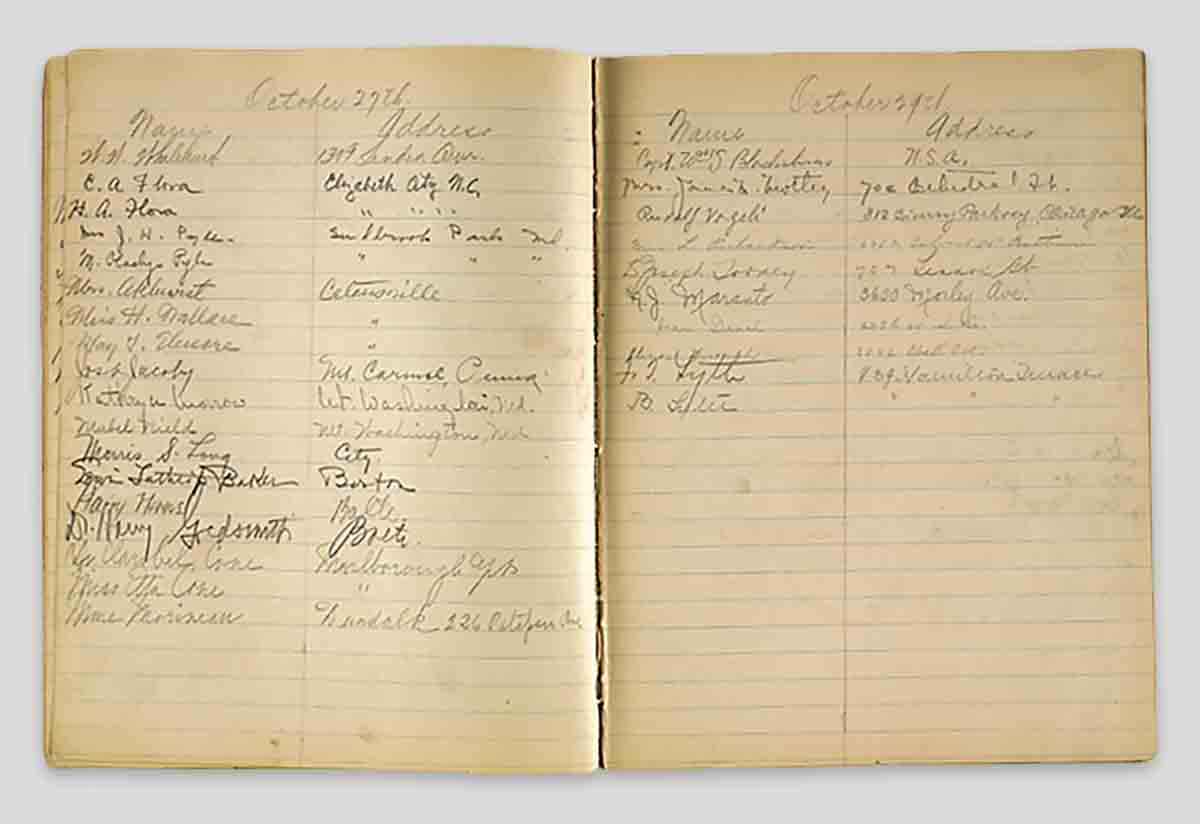

Gallery view at opening of Pope Building, 1929; Arnold Lehman, Adelyn Breeskin, Charles Parkhurst, Trude Rosenthal, and Tom Freudenheim, 1983; Visitor registry for first Baltimore Museum of Art exhibition, signed by the Cones, 1923.

To this point, it was mostly a repository for objects—objects meant to educate and inspire—and a venue for lectures and musical performances, which proved popular. In fact, more than 1,200 people turned out for a concert of religious music in 1933. That same day, over 200 people were turned away from a music-appreciation lecture.

Celebrating 100 years

Fall events marking the BMA’s first century.

100th Anniversary Gala

The glamorous gala will include great music, lavish decorations, and fine food. Word is that it’s already sold out, but you can get on the BMA’s waiting list and hope.

November 15 | 6 p.m.-12 a.m.

Party of the Century

A more rockin’ affair, the party

features dancing, specialty

drinks, birthday cake, “art

activities,” and a few surprises.

November 15 | 8:30 p.m.-12 a.m.

BMA 200 Time Capsule

The time capsule embedded in

the East Wing in the early-1980s will be opened and its contents examined. Visitors can then help assemble and install a new time capsule that will be opened in 2114.

November 16 | 2 p.m.

American Wing

Opening Celebration

The daylong event marks the reopening of the BMA’s historic front entrance and the renovated American galleries. There will be live music, artist demonstrations, gallery talks, storytelling, and treats for the whole family.

November 23 | 10 a.m.-5 p.m.

Cheered by such a response, then-director Roland McKinney, in a letter to board chairman Henry Treide, noted, “People seem to feel that the Museum belongs to them and show that they are sincerely proud of it and its activities.”

But the “people” were mostly upper- crust, privileged, and white, a fact duly noted in a 1937 Carnegie Corporation report. “[Baltimore] cultural institutions (outside of the library and the schools) have appealed to, been intended for, and been supported by a pretty small minority,” it concluded. “They need to be opened up, for the viewpoint of the entire community and its needs. . . . No cultural institution, in Baltimore or anywhere else, is worth its salt until and unless it is democratized.”

Local artists were feeling slighted, as well. “We, the living, resent being left to work in a vacuum of indifference and neglect while so much of the dead past is exhausted [by the BMA],” the president of the Artists’ Union of Baltimore complained to The Evening Sun in 1937. The writer of the letter was Morris Louis, whose work, decades later, would become a cornerstone of the BMA’s contemporary collection.

Treide responded with the extensive community outreach survey in 1937, which resulted in, among other things, a “Labor in Art” show the following year and then, in 1939, the city’s first exhibition of African-American art, which included work by Jacob Lawrence. The latter show drew over 12,000 visitors in two weeks.

Beyond that, a glance at 1938-1939’s calendar of events shows the BMA becoming more diverse. In addition to the exhibition of “Contemporary Negro Art,” it lists shows of Religious Art, Non-Objective Art, Hindu Metal Work, Six Living American Artists, locals Herman Maril and Reuben Kramer, and posters created by public-school students. Among the lectures are talks on “Modern Typography” and “Low Cost Housing in America and England.”

But what followed transcended the city limits, as breathtaking bequests brought the BMA national and international attention and upped its standing considerably within the museum community.

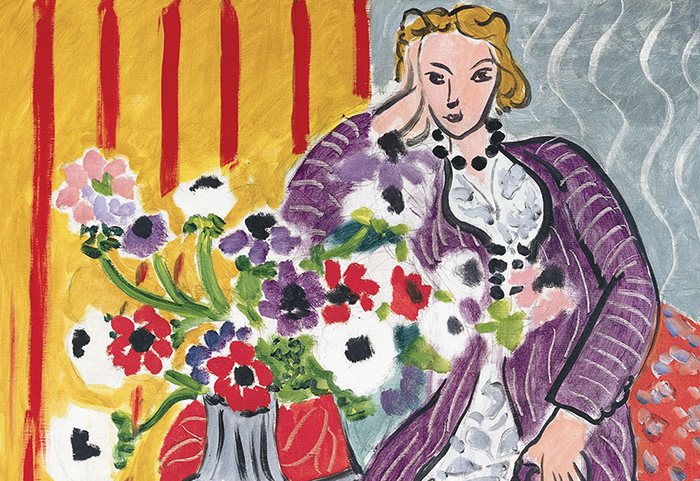

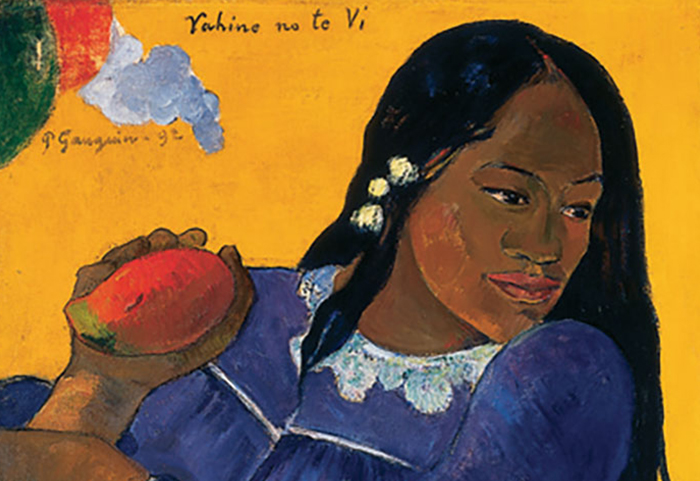

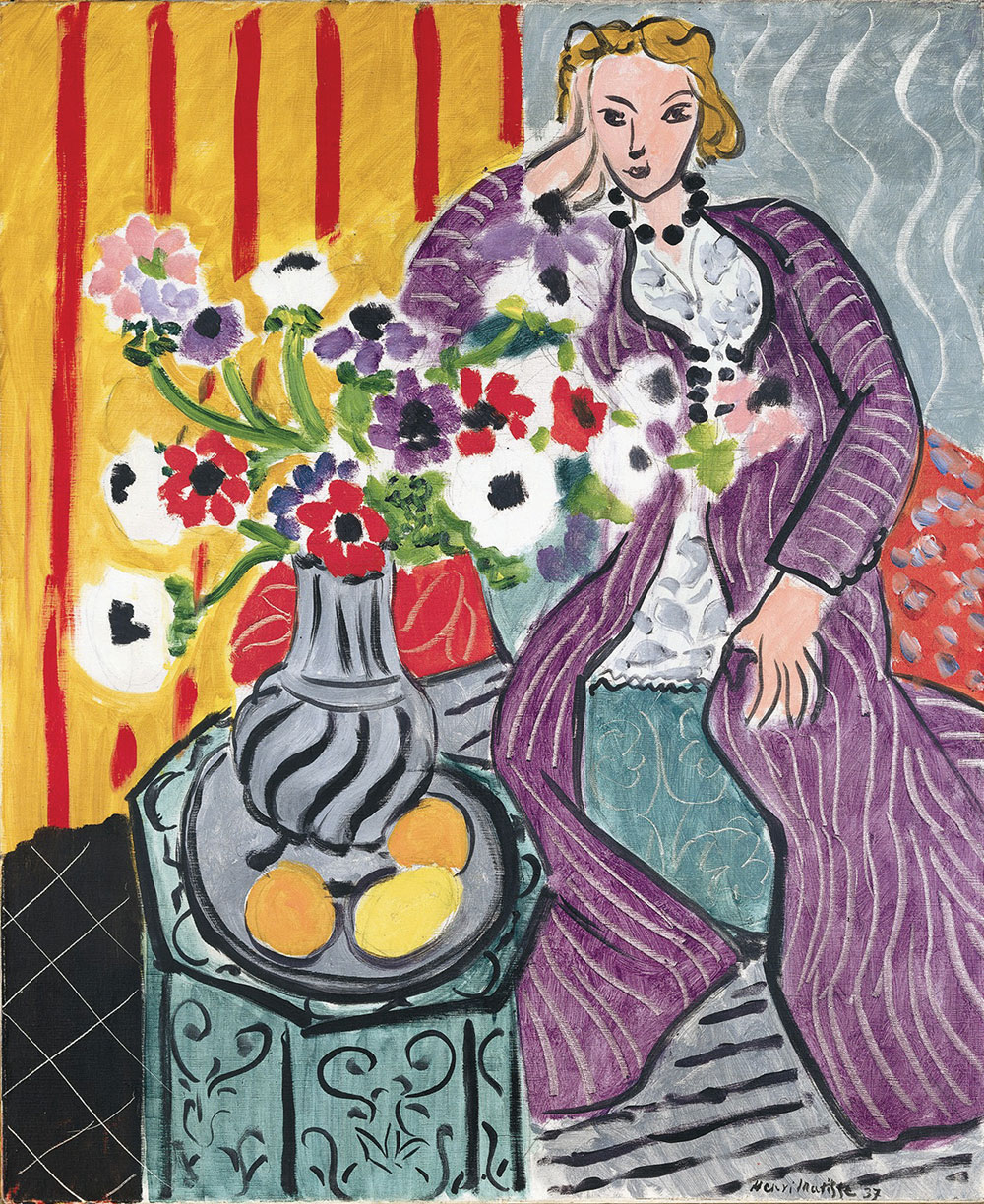

Children’s art class at BMA’s Young People’s Art Center, 1950s; Saidie May, artist and collector; 19th-century African palm wine cup from the Wurtzburger Collection. Jackson Pollock’s Water Birds was given to the BMA by May; The Cone Collection includes an extensive selection of acclaimed Matisse paintings; Gauguin’s Woman of the Mango is another Cone Collection highlight.

Adelyn Breeskin and Trude Rosenthal deserve much of the credit. The two women are often mentioned in the same breath, and for good reason: The museum acquired its most vaunted collections during their tenures, and, in many ways, the duo shaped the BMA as we know it.

Breeskin started as a curator in 1930 and was director from 1942 to 1962, meaning she guided the institution from World War II into the era of civil rights and The Beatles. The daughter of Dr. Dohme, who donated the BMA’s first painting, she was the world’s foremost expert on painter Mary Cassatt and also put together the American component of the 1960 Venice Biennale. (Her exhibition included work by Philip Guston and Franz Kline.) A 1984 tribute by the American Association of Museums claimed Breeskin’s work would be “permanently etched in the fertile ground of American art history.”

Rosenthal came aboard in 1945 as research director and worked her way up to chief curator, before retiring in 1968. She was an art historian with impeccable credentials and curated the BMA’s 50th anniversary exhibition in 1964 and “From El Greco to Pollock,” which nodded to the scope of her scholarship, in 1968.

“They were serious, and they knew what they were talking about,” says Richardson. “At that time, their mission was focused inward and was all about preserving great works of art and publishing important art history. This was their mission in life, to take good care of this collection that belonged to the people of Baltimore.”

“This was their mission in life, to take good care of this collection that belonged to the people of Baltimore.”

The permanent collection swelled substantially on their watch. The bequests and gifts included the Jacob Epstein Collection of Old Master paintings, with van Dyck’s Rinaldo and Armida (1946); the Wurtzburger Collection of African and Pacific Islands art (1950s); the Saidie A. May Collection of sculpture and paintings, which consisted of everything from 16th-century bronzes to work by Marc Chagall, Piet Mondrian, and Jackson Pollock (1951); and the renowned Cone Collection (1949).

Although often overshadowed by the Cones (who were cousins of hers), Saidie May rivals the sisters when it comes to what she did for the BMA. The daughter of a prosperous Baltimore shoe manufacturer and an artist herself, she travelled extensively and built her collection around what the Cones had, filling in holes and often sending her purchases directly to the museum. She also bankrolled a Renaissance Room of objects from various European cultures, a Members’ Room that showed only contemporary art, and a Young People’s Art Center for children’s exhibitions and classes. (The Renoir painting, On the Shore of the Seine, that was stolen in the 1950s and returned to the BMA earlier this year came from May’s collection.)

“There is scarcely a single museum department . . . to which she has not contributed,” noted Breeskin at the children’s wing opening in 1950. Another speaker compared May to Johns Hopkins, George Peabody, and Henry Walters.

When asked which person she admires most from the BMA’s long history, Bolger cites May, calling her “a bold, fearless woman at a time when women weren’t as liberated. She was a model for what this museum should be: a repository for the greatest art in the world, but also open, adventurous, and humane. And she loved Baltimore.”

The famed Cone sisters were more conflicted about their hometown. Claribel died in 1929 and left her part of the collection to Etta, her sister. Claribel’s will stated she wanted the complete collection to remain in the city “if the spirit of appreciation for modern art in Baltimore becomes improved, and if the Baltimore Museum of Art should be interested” in receiving it.

Sensing an opening, representatives from The Museum of Modern Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the National Gallery of Art all inquired about it, and various curators and directors turned up at Etta’s apartment to schmooze and salivate over the Matisse, Picasso, Cézanne, Gauguin, and van Gogh paintings.

Ultimately though, Breeskin’s and Rosenthal’s personal relationships with Etta—reminiscent of their dealings with Saidie May and others—trumped such efforts. Etta consulted Breeskin and Rosenthal about purchases and sometimes asked the pair to suss out potential acquisitions in New York for her. When Etta died in 1949, she left the entire collection, all 3,000 items, to the museum.

In 1957, the Cone Collection moved into a BMA wing built especially for it and assumed its position as one of the most astonishing and important art collections in the world. Since then, public perception of the BMA has been inextricably linked to the Cones’s prescient taste. “The Cone Collection quickly became what everyone associated with the museum,” says deputy director of curatorial affairs Jay Fisher, who’s worked at the BMA for almost 40 years.

But as the cultural landscape shifted dramatically over the next decade, the BMA was forced to reflect on its role in the broader community. African Americans, women, and young people clamored for more of a voice in all aspects of society. Was it time for the BMA to look beyond its collections (like Treide in the 1930s) and become more outwardly focused and inclusive? Or was it above the fray?

Director Charles Parkhurst’s report to the Board of Trustees in October 1966 indicates where the BMA felt it stood at the time. After noting that the world was “moving toward egalitarianism,” Parkhurst wrote, “Against this stream a museum, like an institution of higher learning, obstinately stands out as justifiably aristocratic, charged with maintaining its role not for the lowest common denominator of its audience but . . . [to those] who crave commitment to a higher vision. The museum is reduced to nonsense the instant it abandons this aristocratic principle.”

Parkhurst ultimately concluded: “We cannot pander or succumb to popular demands or personal tastes.”

By the time Parkhurst resigned in 1970, the BMA was beset by anemic attendance, declining membership, and noticeably fewer exhibitions. It was, according to an Evening Sun editorial, “lacking in clear ideas as to its own next directions.”

The next direction came from, of all places, Berkeley, California.

Tom Freudenheim chose what he considered a conservative outfit for his interview with the BMA board in 1971. At the time, the 33-year-old Freudenheim was assistant director of the Berkeley Art Museum at the University of California, Berkeley and, prior to applying for the job, “had no impression of the BMA one way or the other. I knew about the Cone Collection and that’s about all.”

He selected a pinstripe suit with flared pants, a striped shirt of six different colors, and a polka-dot tie that, color-wise, matched the shirt. Some members of the buttoned-down board were shocked—someone on the search committee even told Freudenheim they didn’t like beards—but, they hired him anyway (facial hair and all), aware of a profound need for youthful energy and new ideas.

“The 1960s were just occurring in Baltimore,” recalls Freudenheim, “people were re-examining the meaning of public institutions and how they could be more relevant. With that in mind, I wanted to make the BMA feel as open as possible.”

The Stars Come Out

A run-down of iconic artists who have visited the BMA.

Edward Albee

| Playwright

1963

Lectured on “The Theater Today: Several Forms of Absurdity.” Merce Cunningham w/ John Cage

| Dancer and composer

1964

Lecture and demonstration by Cunningham, accompanied by Cage, his musical director. Martha Graham

| Dancer

1941, 1949

Dance performances by Graham and members of her company. Marcel Duchamp

| Artist

1963

Delivered a lecture titled “Apropos of Myself.” Andy Warhol

| Artist

1975

Book-signing for The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) in conjunction with the BMA’s Warhol exhibition.

Freudenheim grew up in Buffalo, NY, within walking distance of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery. “I would pop in and out of the museum all the time, because it was a comfortable place to be,” he says. “That led me to think of a museum as a park, as opposed to a performance. You should be able to walk in and out as you please. You might stay for 15 minutes and look at one piece, or you might stay all day.”

He instituted family days, emphasized community outreach, and expanded the BMA’s presence in the metropolitan area through traveling exhibitions and satellite sites at Charles Center and The Mall in Columbia.

“It felt like all these things were part of some movement,” he says. “[William Donald] Schaefer had just been elected mayor, and he made cultural life an important part of his administration. I didn’t feel like I was just a museum director—I felt like I was part of something exciting. It was a time for taking risks and experimenting.”

Freudenheim hired a former colleague, curator Brenda Richardson, from the Berkeley Museum to take some of those risks and expand the contemporary collection. Richardson curated a succession of groundbreaking shows, including, early on, an Andy Warhol exhibition (1975) and a showing of Frank Stella’s Black Paintings (1976).

Thanks to her, says Freudenheim, “The BMA became a significant force in exhibitions of contemporary art in this country. Bringing Brenda to Baltimore is one of the things I’m most proud of.”

Such exhibitions continued under Freudenheim’s successor, Arnold Lehman, who took over in 1979. Lehman believed the museum remained at something of a crossroads with regards to building an audience, and that it was critical to expand upon Freudenheim’s efforts.

“Since 1914 the community has grown, making greater and more varied demands to which the museum must respond,” Lehman noted in his 1980 long-range plan. “There are two choices for the future. The Museum can maintain a status quo and become a mausoleum. The Museum can be progressive, always ready to meet changing educational and community demands. The status quo requires lip service only to responsibilities. Progress demands total involvement.”

Lehman went for it. A prodigious fundraiser, he increased the endowment exponentially, pushed for a new Contemporary Wing that opened in 1994 (featuring a stunning collection of recently-acquired Warhols), and wholeheartedly supported Richardson’s discriminating exhibitions. In fact, they worked together on some shows, including 1997’s A Grand Design: The Art of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Lehman was also known for championing pop-culture fare that brought more people into the building. For every Gilbert & George or Anne Truitt exhibition, there was a show of carousel horses or the art of Dr. Seuss. “Slowly but surely, we saw positive results with regards to audience,” says Lehman.

Attendance eventually tripled and membership increased nearly 400 percent.

But money was always an issue, and budgets remained tight. “It was hard raising funds to match our ambitions,” says Lehman, “and besides, nothing gets cheaper.”

In 1982, Baltimore City required the BMA to charge admission and turn over the proceeds to help offset the city’s portion of the museum’s operating costs. “Here we were trying to get people in the door, and they threw up this huge barrier to people coming in,” says Jay Fisher. “And the price went up and up, making it harder for families to come.”

And still, roofs leaked as the building showed its age, and the local artist community continued to feel slighted.

Bolger, who took over after Lehman left for the Brooklyn Museum in 1997, addressed both issues. The evidence is all around. In her office, for instance, a framed piece with the words “Forward In All Directions” dripping down the canvas hangs behind her desk. Its presence in the director’s office makes a statement in two important ways: there’s the message, obviously, and also the fact that it’s the work of a MICA graduate, Colin Benjamin.

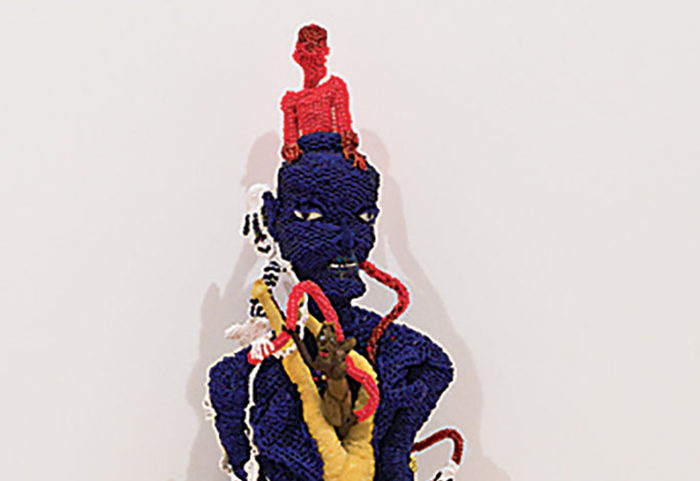

Claribel and Etta Cone with Gertrude Stein; current BMA director Doreen Bolger; work by Baltimore artists Jimmy Joe Roche, Richard Cleaver, Grace Hartigan, and Joyce Scott recently on view in the BMA’s Contemporary Wing.

Upstairs in the Contemporary Wing, the “Symbolic Bodies” gallery recently included work by no less than four Baltimore artists: Richard Cleaver, Grace Hartigan, Jimmy Joe Roche, and Joyce Scott (the subject of a 2000 retrospective, Kickin’ It with the Old Masters, an exhibition many consider to be a turning point in the museum’s relationship with city artists). The wing also features locals in its Front Room gallery from time to time, and its interactive space was initially designed by MICA grads Nolen Strals and Bruce Willen of Post Typography. And then there are the annual Sondheim and Baker Artist Awards exhibitions.

“Baltimore is home to an amazing community of artists,” says Bolger, who’s known for frequenting openings around the city. “I feel very strongly that I need to be out in the community, not just waiting for the community to come here to the museum. It’s very important to recognize artists and encourage them, because their energy, in terms of revitalizing the city, is critical.”

As she speaks, power tools can he heard humming and whirring, a sound that’s become familiar since Bolger’s arrival. As the 100th anniversary approaches, all the museum’s galleries have been renovated, and most of its collections have been re-imagined and reinstalled. Thanks to new roofing, the galleries no longer leak.

But the most significant development of the Bolger era has nothing to do with curatorial decisions or architectural plans: It has to do with access. When she eliminated the admission fee in 2006, Bolger tapped into and enhanced the common mission shared by Lehman, Freudenheim, and directors stretching all the way back to Levy: bringing more art to more Baltimoreans.

The move ensured that the inside of the BMA would increasingly look more like the city around it. Any doubters should just ask Carl Carver.

Carver claims the return to free admission resulted in the most profound change during his long BMA career. “Once that happened, I saw more Latinos and Asians at the museum, as well as more blacks,” he says. “Now, you see all different kinds of people, which is the way it should be.

“After all, it is The Baltimore Museum of Art.”