Arts & Culture

Guitar Hero

Paul Reed Smith has joined the likes of Fender and Gibson in the pantheon of electric guitar makers.

“Guitars are almost like iPods,” says Paul Reed Smith. “I’ve never seen anybody in a bad mood with an iPod in their ears. It’s a mood adjuster. It’s almost like really sophisticated, expensive OxyContin.”

Smith is musing on the power of the six-string “mood adjusters” he’s been creating for 35 years, the last 25 as the pioneer behind Paul Reed Smith (PRS) Guitars, now the third largest electric guitar manufacturer in the nation. (Iconic old lions Fender and Gibson are numbers one and two, respectively.)

Seated at a conference table in his office at the PRS factory, a 100,000-square-foot facility on Kent Island, Smith, 54, is dressed in jeans and a long-sleeve T-shirt rolled up to his elbows. He is tall and lean, his silver-gray hair cropped short. He keeps a guitar pick wedged between his thumb and index finger and carries it with him from appointment to appointment, using it as needed. Doctors have stethoscopes; Smith has guitar picks.

On the surface, he presents a reserved, professional air, but when he speaks, Smith’s eyes widen behind his spectacles. His voice, infused with an intense musicality, shifts in levels—from a weighted whisper to a bright melody—when discussing his beloved instruments.

“I think Joseph Campbell called it ‘aesthetic arrest,'” says Smith, “where you hear a sound, you go. . . .” He takes in a quick, deep breath, as if he’s just seen the Grand Canyon for the first time. “It kind of arrests you a little bit, right? That’s the goal of any good art. We’re making art here and tools to do jobs. It’s a very interesting combination.”

Poster-size sheets of white paper with specs lay before him on the conference table. They’re reminders that Smith’s job isn’t just some rock ‘n’ roll fantasy. He has a lot on his mind, these days. In fact, a tangible sense of excitement and urgency can be detected throughout the factory—from the top down, from this conference room to the shop floor. PRS is about to unveil its 25th Anniversary guitars at the National Association of Music Merchants (NAMM), one of the largest industry events in the world; the launch of new lines of acoustic guitars and guitar amplifiers is already underway, and today is the employee awards ceremony.

Jon Wasserman, a research and development engineer, pops into Smith’s office holding a guitar. “Hi, Jon,” Smith says. “What was wrong?”

Apparently, a pick-up needed adjusting on one of the guitars; Jon explains the modification that’s been made, and he and Paul duck into a sound room next to the amp department. Smith sits on a stool, plugs in the guitar, and starts strumming chords. “It’s still not right,” he tells Wasserman, before quickly adding that he’s “almost there.”

Smith obviously likes being hands-on, the ultimate quality-control guy, who interacts with employees and remains an integral part of the process. “The most enjoyable part of my day is when we get it right,” he says.

Smith has been getting it right for decades, transforming a specialized product and boutique operation into a recognizable brand and formidable company that employs 235 people and generated $35 million in sales last year. The PRS catalogue boasts more than 50 electric guitar models, acclaimed for their playability and design. In addition to distinct tonal qualities, they’re known throughout the industry for their elegant body shapes, colorful finishes, and trademark symbols, such as the silhouetted birds detailed in the fret inlays. (They were inspired by images from his mother’s bird-watching books.)

“I’ve always maintained a Paul Reed Smith is the Lamborghini of guitars,” says Paul Riario, technical editor for Guitar World magazine. “Each one is a custom, finely tuned instrument built for speed and awe.”

Riario describes Smith as a “CSI guitar specialist.”

“Paul is already a visionary designer, but the one thing that remains constant is he possesses a creative unrest to improve his already popular guitars,” Riario says. “He is also an accomplished guitar player, which is key, because he’s able to distinguish what makes a guitar tick when he’s exploring a new sound or considering materials to begin construction for future guitar models.”

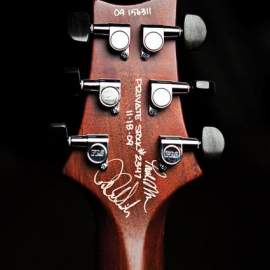

Adding to PRS’s street cred is a stable of “signature” and endorsement artists, a diverse array of heavyweight guitar-slingers, including Carlos Santana, Dave Navarro of Jane’s Addiction and Red Hot Chili Peppers fame, and country picker Ricky Skaggs.

Smith realized the importance of such endorsements early in his career.

For awhile, in the 1970s, he was building guitars at his parents’ house by day, and hitting up the likes of Ted Nugent (and his guitarist, Derek St. Holmes) and Peter Frampton at local concert venues at night. “I wouldn’t make a sale every time,” he recalls. “It was a sale one out of 10 times. I was scared. I did it anyway. I met Stanley Clarke once. Couldn’t control my voice. ‘Hi Stanley . . . I . . . I . . . make guitars,'” Smith says in an exaggerated, high-pitched squeal. “I was so frightened. He said, ‘Calm down,'” Smith laughs at the memory.

When he met Carlos Santana at the Capital Centre in 1976, trying to make a sale to one of his heroes wasn’t what scared him. “I was very frightened when he asked me to play with him,” remembers Smith. “I said, ‘Are you kidding me?’ That scared the hell out of me.”

Santana recalled their meeting in the 2008 summer edition of Signature, the official PRS magazine. He remarked on the guitar Smith had brought him, “a beautiful guitar that was cherry red, a different red than I’d ever seen.” He also noted that it had “a different kind of tone to it, the varnish was different, everything was.”

But the iconic guitarist also picked up on something else, something equally important. “He had really bright eyes,” said Santana. “And he was just filled with hope and future possibilities.”

Raised in Bowie, Smith grew up surrounded by music. When Smith was 5, his father bought him a ukulele, and he also learned to play his mother’s classical guitar. After hearing The Beatles and Jimi Hendrix, he became obsessed with guitars and played in a few local bands.

But early on, he knew what he wanted to do. “I dreamed about it when I was 14, 15 years old,” says Smith. “The story is—I don’t know if it’s true or not—that Christina Aguilera used to sing to her dolls on her bed when she was like 12 or 13, right? I wasn’t singing to dolls on the bed, but I had visions of being a guitar maker when I was young.”

He made a bass—affixing the neck from a Japanese model to a body he constructed—during his senior year at Bowie High. He also landed a job at the Washington Music Center as a repairman, which allowed him to hone his craftsmanship and skills.

He went on to St. Mary’s College of Maryland, the only school that accepted him. “I even applied to Paul Smith College in upstate New York and said, ‘Come on, my name is Paul Smith,'” he says. “They wouldn’t take me.”

While at St. Mary’s, Smith built his first “real” guitar as an independent study project. One guitar led to another, and Smith eventually moved into a small shop in Annapolis. There, a handful of craftsmen churned out one guitar a month.

“Paul’s dynamic personality was as evident [then] as it is now,” says Jack Higginbotham, President of PRS Guitars. Higginbotham was one of the first builders Smith hired for the shop 25 years ago. At the time, Higginbotham had no experience making guitars—he was a local musician. “I remember going home and telling my girlfriend that I just met a really interesting guy who I think is going to do something in this world,” says Higginbotham. “The way I think of it is: Paul had a dream and brought us into his dream.”

To fully realize that dream, Smith moved to a larger manufacturing facility—on Virginia Avenue in Annapolis—and officially launched PRS Guitars in 1985. That same year, the company introduced its first model, the PRS Custom, at the Winter NAMM. Guitar Player called it “a wonderful, subtle instrument for discerning players who know the difference,” and PRS began its ascent in the guitar market.

A year later, Smith fortuitously met Ted McCarty, who ran Gibson in its heyday and helped design the classic Les Paul and Flying V models. (The towering guitar affixed to the Hard Rock Café is a McCarty design.) McCarty became a crucial mentor, and Smith hired him as a consultant. “I wasn’t guessing how it was done,” says Smith. “He told me how it was done.”

The veteran designer helped the young entrepreneur enhance and evolve his designs and also provided a role model for Smith, who was growing into his position as the head of a blossoming guitar company. “He basically handed me the baton and said, ‘I support you,'” says Smith. “It was a big deal for him to align himself with us.”

The PRS McCarty model the company debuted in 1994 took on added significance after McCarty passed away in 2001. By that time, PRS had moved to its current Kent Island facility, where it now produces between 40 and 75 guitars a day.

At 2:30 p.m., employees gather in the lunchroom for the awards ceremony. The awards are given for perfect attendance over the course of several years. (Perfect attendance includes not being late.) It’s a no-frills affair that lasts about 20 minutes, and then it’s back to work.

Smith, donning a black sports coat, stands behind a microphone and presents the awards, which range from new guitars to plaques and gift certificates. He does it all with a soft-spoken casualness that conveys respect and gratitude.

Kenny Dennis, who does finishing work at PRS, says the feeling is mutual. Dennis has worked 10 years for the company and never missed a day—so he gets a plaque. He says all the employees know that Smith has done almost every job in the factory at some point in his career, and that carries a lot of weight.

Smith and his staff are also aware that the economy has taken a toll on PRS, which had to lay off 35 employees last year. “I think that the art going on in this building [has] been very strong,” notes Smith, “and one of the reasons we’re still alive in this economy is because of that.”

He echoes that sentiment when asked about the significance of the 25-year anniversary. “It means we survived,” he replies. “The only thing I think when I look backwards is I can’t believe that kid did that. I look at the pictures of myself, and I look at the guitars that are in the archives and I can’t believe that kid did that. It doesn’t even seem like me.”

And he’s convinced his best work lies ahead of him. He ticks off the names of his predecessors: “D’Angelico, McCarty, Fender, Stradivari—you name ’em,” he says. “They got good around 50, 55 years old. Guitar makers don’t get good until they’re my age.”