Earlier this week, Baltimore icon John Waters announced that he will be leaving many pieces from his personal art collection to the Baltimore Museum of Art when he passes away. And of all the creative works that Waters is giving the institution, one is truly a first.

Forget the Roy Lichtenstein or the Cy Twombly or the Andy Warhol. There’s an abstract expressionist painting in the collection that’s an explosion of pinks and blues, an allegory of dark and light, strong and weak. It’s reminiscent of a de Koonig, but no, it’s a Betsy.

“Oddly vaginal, the work on paper strikes an uneasy balance between the cliché blue of boyhood, and the hackneyed pink of femininity,” Waters writes in an objective appraisal of his own possession. “It is a conflicted vision—alarming and even violent in the middle.” He goes on to say that it includes “unhesitating gestures,” “nuanced marks,” and “digital stabs at clarity.”

What makes this painting especially remarkable is that it’s the work of a chimp. But not just any chimp. Betsy the finger-painting chimpanzee from the Baltimore Zoo (now the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore.)

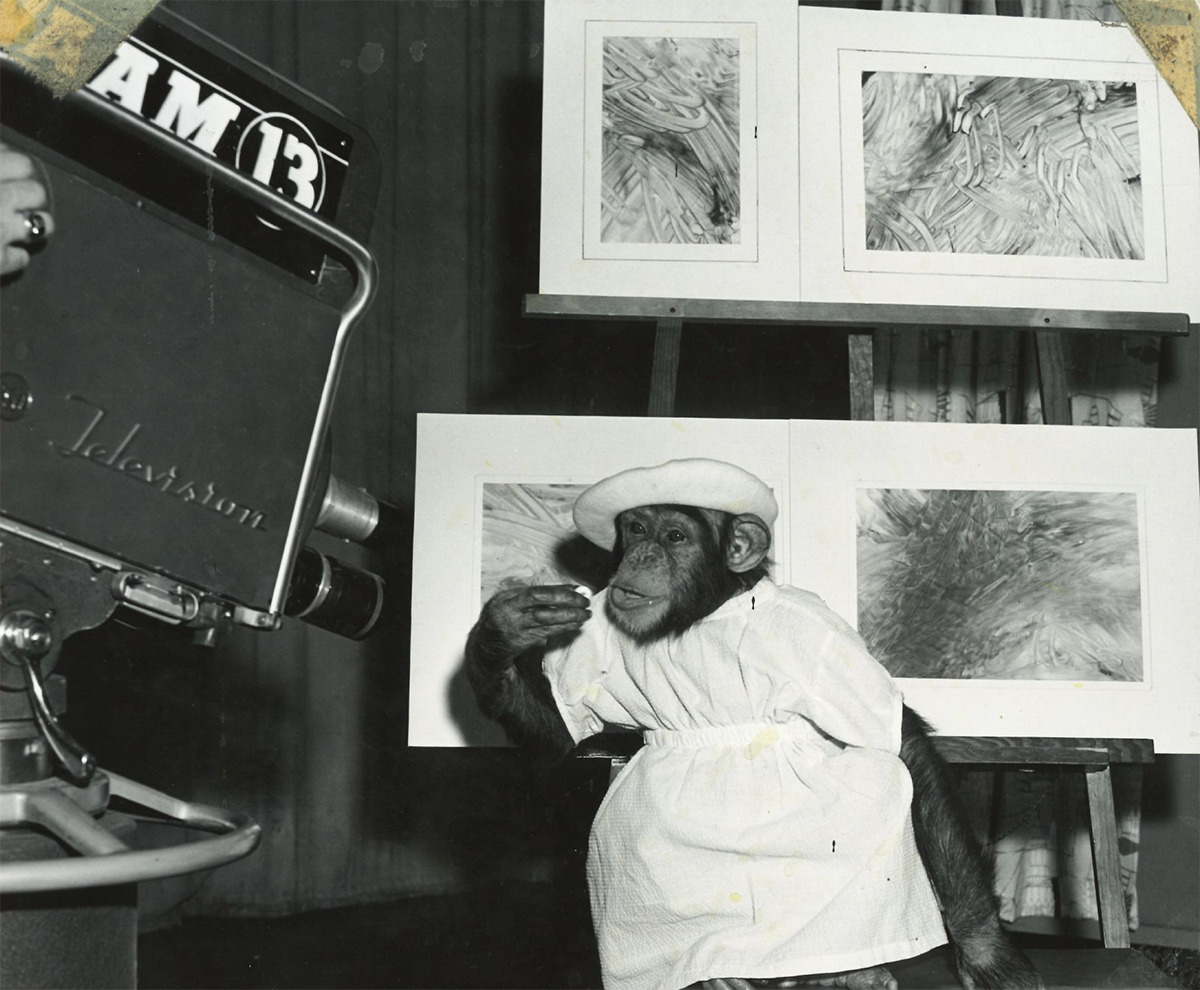

Betsy, the first famous monkey painter fondly known as the “Paintin’ Primate,” the “Picasso of the Primates,” the “First Lady of Primate Painters,” the “Frida Kahlo of finger-painting.” Betsy, the star of This Is Your Zoo, the local 1950s-era television show hosted by the inimitable Dr. Arthur Watson, zookeeper extraordinaire. The black-and-white show watched by a prepubescent John Waters in his pajamas on Saturday mornings. The show that inspired Waters to be who he is today.

Betsy’s painting is one of 375 works that Waters has agreed to give to the Baltimore Museum of Art when he dies. The museum has been around for 106 years and is the steward of more than 95,000 objects, but this will be the first work of art in the museum’s collection that was created by a non-human being.

A primate like humans, yes. A chimp who may have shared a common ancestor with humans seven to 13 million years ago, sure. But a wild animal, born in Africa, in the last century. Let that sink in. Betsy has done it. Betsy the chimpanzee has shattered the inter-species ceiling.

“It seems Betsy is a first for the BMA,” confirms senior director of communications Anne Mannix-Brown, who we can only guess is happy to answer questions about something other than the bathrooms that will be named after John Waters in honor of his gift.

“Betsy is going right to the museum!” Waters agrees. “Betsy is most definitely ending up, finally, in a museum!”

It’s a happy ending for Betsy, who was born in Liberia, crated and shipped to Baltimore at age 2, and lived only nine years in all, from 1951-1960. During that time, wearing a smock and sometimes a beret, she created hundreds of paintings on and off live TV, sometimes turning out four to 12 an hour.

In addition to her local shows, Betsy traveled to New York and appeared on The Garry Moore Show on CBS and Tonight on NBC. In 1957, she had a rivalry with Congo the male chimp from the London Zoo, who worked with oil and actually could hold a paintbrush. The zoo sold her paintings for $40-$50, investing the money back into its operating fund. But despite her status as an international phenomenon, and her Baltimore background, she never before had a work of hers accepted into the permanent collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art. (Her work was, however, featured in the Home and Beast exhibition at the American Visionary Art Museum and in a retrospective at the late, lamented Dime Museum.)

Waters, 74, received one of Betsy’s paintings as a gift from the zoo when he turned 70, and he keeps it in his house in Baltimore. He calls it his “monkey masterpiece.”

But Waters was a fan long before then, going back to the This Is Your Zoo days. He even wrote a chapter about her in his latest book, Mr. Know It All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder. He told the story of her brush with greatness, how she rose to the pinnacle of the animal artist world only to have her life cut short when she was crushed by Spunky the Monkey (who very well might have been purchased with money from her paintings.) Horrified zoo staffers took her to a human hospital for pioneering open-heart surgery in effort to save her life, but it was unsuccessful. Waters called it, “an artwork horror story to rival Jackson Pollack’s fatal car crash.”

In his chapter, entitled “Betsy,” Waters advised readers to think about investing in works made by primates, especially those from the second half of the 1950s—a period he called “The Golden Age of Monkey Art.” He predicted that Betsy’s work would grow in value once it was discovered by a younger generation of buyers priced out of the human art market. He said the time was right for a Betsy revival.

Now that Betsy’s work will be at the BMA, alongside Warhol and Lichtenstein and Twombly, does Waters think she’ll finally get the recognition she deserved? Will people finally realize her work has value? As a longtime collector with a good eye, Waters knows talent when he sees it.

“It’s always been of value,” he says.