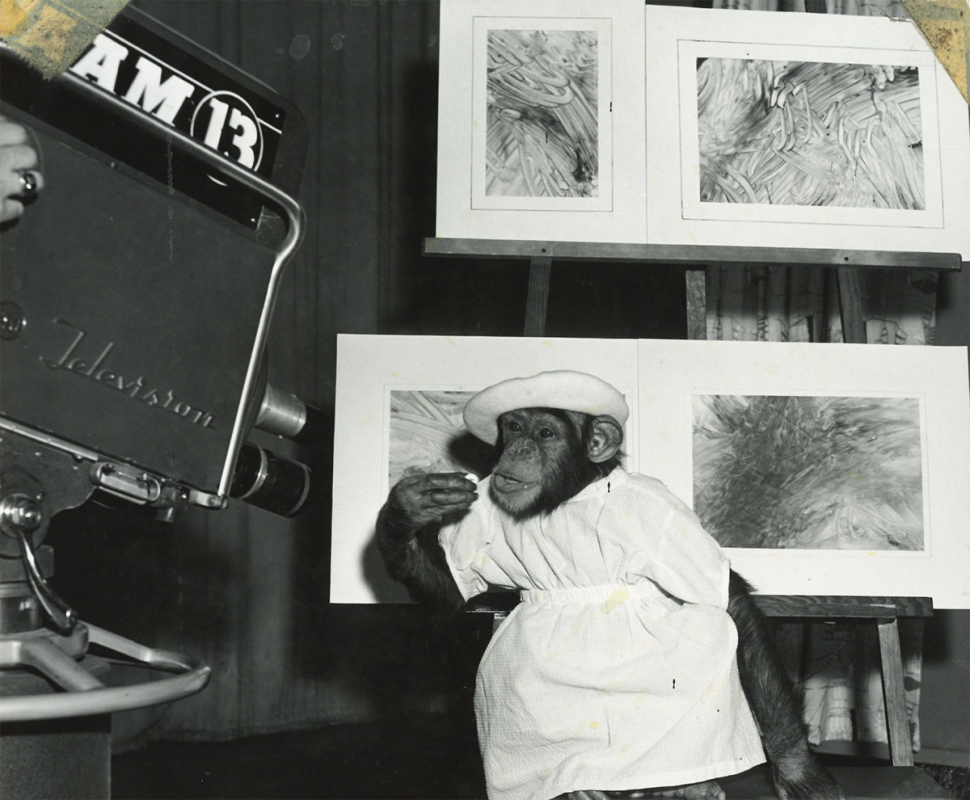

If you grew up in Baltimore during the 1950s, you may remember Betsy, a chimpanzee from the-then Baltimore Zoo who could paint with her fingers. Dubbed the Paintin’ Primate, Betsy was a highlight of This Is Your Zoo, a weekly program on WAAM-TV (now WJZ) whose host was the inimitable zoo director, Arthur Watson.

Seeing Betsy in her smock (and sometimes a beret) dash off painting after painting might have made you think that all apes could paint, and that you had better get on the ball and do something to keep up with them. For those long-ago, black-and-white TV days, it was a weirdly inspiring, bizarrely Baltimore story.

At least one Baltimorean remembers watching Betsy on TV and the lasting effect it had on him.

In his new book, Mr. Know-It-All, filmmaker John Waters paints Betsy as a star of the airwaves and shares his memories of her brush with greatness. He was about 12 when she made her TV debut. In a chapter entitled “Betsy,” Waters recounts her brief but colorful life, from her arrival in Baltimore from Liberia at the age of 2, to her rise to the pinnacle of the animal artist world, to her tragic death following a painful encounter with Spunky the Monkey, and the pioneering but ultimately unsuccessful surgery that failed to save her life.

As Waters tells it, Betsy was so popular with her finger painting at the zoo, now known as the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore, that its “hambone” director decided to make her a star on his local TV show, and the zoo reaped the benefits.

“After a contest on the show to select a name, Betsy made her debut and was an immediate hit,” Waters writes. “She painted on live TV. Her local publicity got so big that she had to go national. Realizing that he had a star that needed exploiting, Dr. [Arthur] Watson took Betsy on the road. Wearing a white bonnet and carrying a pink suitcase, she arrived in New York City for a round of appearances, including The Garry Moore Show on CBS and Tonight on NBC. Her work was already selling, too, raising much needed money for the zoo animals’ fund back at home.”

According to a report from the zoo’s archives, Watson was experimenting with ideas for entertaining children on his weekly show when he first put Betsy in front of an easel.

“After tasting a bit of magenta and yellow paint and chewing on a paintbrush or two, Betsy began to smear paint on paper with enthusiasm,” the zoo document says. “Her moods influenced the type of paintings produced,and her production varied from four to twelve paintings in an hour. Utilizing tempera paint on paper and a technique similar to finger-painting, Betsy also used her palms, elbows, feet, and tongue to produce paintings . . . that were compared to the works of abstract expressionist painter, Willem de Kooning.”

Watson coaxed other chimps to paint, but no one could perform like Betsy. Soon, other zoos attempted to get their animals to produce paintings, Waters writes, and in 1957 there was an international rivalry between Betsy of Baltimore and Congo the male chimp from the London Zoo, who worked with oil and even “used an actual paintbrush or two.”

Seeking to add a spark of romance to Betsy’s storyline, Waters notes, Watson fixed her up with a “public boyfriend,” but that led to her downfall. After a suitor named Dr. Thom didn’t work out, Watson used money raised from Betsy’s paintings to bring in Spunky the Monkey and made him Betsy’s sham paramour. Unfortunately, Spunky had no interest in painting (or playing the piano either, despite Watson’s best efforts.) Beyond that, he fell on Betsy one day and broke her leg, sending her into shock.

“Betsy was rushed to a human hospital and given emergency treatment including open heart surgery but, alas, she passed away,” Waters reports. “Betsy’s obituary appeared in Time magazine and one Baltimore paper in a front-page story remembered her as the Picasso of the Primates.”

Waters sums up the saga as “an artwork horror story to rival Jackson Pollack’s fatal car crash.” And yet, he says, “for a monkey who lived only nine years, Betsy certainly left her mark in art history.”

Waters uses Betsy as a starting point to write about all the other chimps, gorillas, and orangutans who became animal artists in the second half of the 1950s, which he calls “The Golden Age of Monkey Art.” (Chimps are not the same as monkeys, but both are considered primates, as are humans, according to the Jane Goodall Institute. Most monkeys have tails, while chimps and humans don’t.)

Besides Congo, who was billed as the “Cezanne of the Ape World” and who could draw circles as well as hold a brush, Waters’ list includes Achilla the Gorilla, Alexander the orangutan from the London Zoo, Sophie the gorilla from the Rotterdam Zoo, Dzeta, a pygmy chimpanzee from an animal farm in Belgium, Charles the gorilla from the Toronto Zoo, and Peter the ape from Sweden’s Boras Zoo.

But Waters keeps coming back to Betsy, the “Frida Kahlo of finger painting.” He reports that Betsy brought in $4,500 in second-hand sales of her paintings (her creations typically sold for $40 to $50 each, according to the zoo) and he believes the time is right for a Betsy revival.

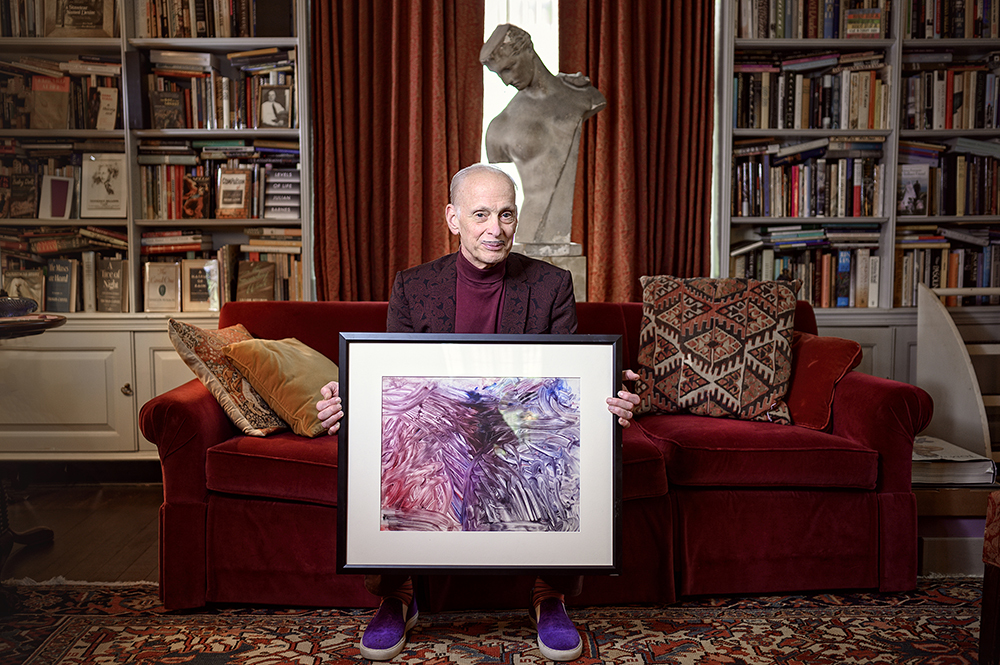

Waters heard somewhere that the zoo may have a stack of unsold Betsy paintings lying around and believes now is the time for the zoo, and art collectors everywhere, to cash in. He writes that the zoo gave him a painting by Betsy for his 70th birthday—he calls it his “monkey masterpiece”—but confesses he wasn’t exactly sure how to hang it because he couldn’t tell which side was supposed to be up.

“Oddly vaginal, the work on paper strikes an uneasy balance between the cliché blue of boyhood, and the hackneyed pink of femininity,” he writes, in his best critic voice. “Yes, it is a conflicted vision—alarming and even violent in the middle, but Betsy’s unhesitating gestures, her nuanced marks and digital stabs at clarity, turn a mere finger painting into an arduous monkey version of Gustave Courbet’s scandalous ‘L’Origine du Monde.’”

Jane Ballentine, senior director of development and communications for the zoo, said there are two Betsy paintings stored away for safekeeping, and she’s unaware of any others still there. But she doesn’t deny that Betsy was a star and an inspiration to others. In fact, she says, the zoo even today has an annual “art auction” at which it sells works by animal artists, including Christmas ornaments and other items featuring markings made by penguins, snakes and ostriches.

Waters, who just turned 73, said that he wrote about Betsy “for all the obvious reasons I talk about” in the chapter: she provides a window into the art world, her paintings represent potential investments for collectors, and she was a local hero who achieved “true stardom.”

He said he hasn’t spoken about Betsy in public before, and his book is the first time he has gone into any detail about her in his writing. He keeps the painting he got from the zoo at his home in Baltimore.

“I had been living with a love of Betsy ever since I started collecting art,” he confides. “But selfishly kept her to myself so I could be her biggest fan in the privacy of my own home.”

While writing about Betsy brought back fond memories, “everything in the book brings back fond memories,” he added.

Part of the advice Waters gives in the Betsy chapter is that now is the time to buy monkey art, especially by Betsy. “There’s only so much work available,” he says. “Once a market is established, the prices will get ridiculous. Betsy’s not around to object.”

But there’s another lesson from the chapter that has nothing to do with investing in art. It’s about following your dreams and living up to your potential. Waters doesn’t come right out and say it, but watching Betsy when he was young seems to have lit a fire under him and inspired him to make his own art. It showed him the power of having a skill and turning it into a brand. If Betsy could find a calling, he seems to say, why can’t we all?