ARTS & CULTURE

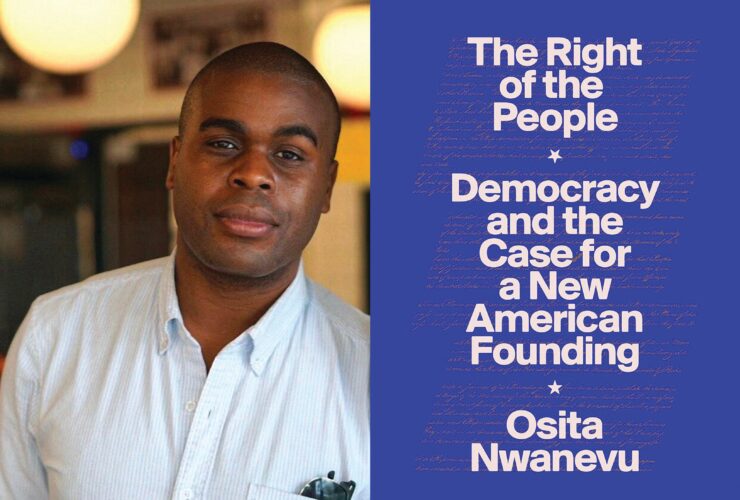

The Chosen One

Jonathon Heyward is the exact right conductor at the exact right time for the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra.

By Max Weiss

Photography by Mike Morgan

Opening Spread: Heyward in front of the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, wearing his signature Converse.

September 2023

on stage at the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall. The assembled musicians, several in their formal concert attire, others in street clothes, are all doing different things: Some are talking and laughing. Some are playing scales. Some are tuning. Some are just making noise for the sake of it.

In the box seats, another group files in—they will be the chorus for tonight’s performance. They crane their necks and peer onto the stage. They squirm. They giggle. A harried minder tries to get them to stand up straight.

Of course, these aren’t members of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, but rather, members of OrchKids, the public-school music program started by Maestra Marin Alsop in 2008. Tonight is their 15th anniversary gala concert and this is the dress rehearsal. They’ll be playing a jazz- and gospel-tinged version of Matisyahu’s “One Day” arranged by Brian Prechtl, a percussionist with the BSO who also chairs the percussion department of OrchKids. He’s on stage now, getting their attention, and doing the warm-ups.

At some point, a tall, impossibly slender young Black man enters from stage right. He’s dressed casually in a blue button-up shirt, grey jeans, and a pair of his signature black Chucks. He’s holding a score.

Prechtl stops the playing to introduce him.

“This is Jonathon Heyward,” Prechtl says, “and he grew up in a music program a lot like this one.”

The kids applaud.

Prechtl turns things over to Heyward, the music director designate of the BSO—at 31 years old, he’ll be both the youngest and the first Black maestro in the orchestra’s history—and he sprints onto the podium.

“Hi everyone, how are you doing?” he says brightly.

“Gooooood.” It’s the rote reply of a bunch of kids who have answered this question way too many times before.

“How are you doing?” Heyward repeats, louder this time.

This time they’re more enthusiastic: “Good!”

“How does it feel to be at the Meyerhoff?” Heyward asks.

There are whoops and cheers.

“I just want you to know that this is your home. This space is your space,” Heyward says.

And he raises his arms and begins to conduct.

Even for this dress rehearsal with a bunch of high-school, middle-school, and elementary students, Heyward’s enthusiasm for music, for conducting, for the fellowship that music creates shines through.

“You’ve got all of your bow for a reason,” he says to the cellists. “You should use all of it!”

“Can you say ‘sss’ like a snake?” he instructs the chorus.

They imitate his “sss” sound. That’s how he wants them to enunciate the word “sometimes.”

“I think you can play louder than that!” he encourages. So they do.

And as he conducts, the music becomes better—the diminuendos softer, the fortes louder, the musical expression more precise.

“Thank you everyone for being amazing!” Heyward says, hopping off the podium, satisfied that they are ready for tonight’s performance. “Bravo!”

Heyward conducts the

OrchKids gala dress rehearsal. —Courtesy of Max Weiss

THEY SAY IF YOU CAN SEE IT, you can be it. But that didn’t really apply to young Jonathon Heyward. He grew up in West Ashley, South Carolina, just outside of Charleston. His father, who is Black, was a chef. His mother, who is white and Yugoslavian, was a waitress. Money was a struggle. He and his younger brother, Anthony, shared a cramped room. At times they relied on food stamps.

It’s not just that there are only a handful of Black conductors on the world stage, even to this day. It’s that young Heyward would’ve had no exposure to them. Classical music wasn’t played around his house—or at any of his friends’ houses.

All that changed when he was introduced to orchestral music at his public elementary school. They were handing out instruments and he picked the cello, not because he was particularly drawn to it, but because the line was shorter than the one for the violin. Things like this happened to Heyward a lot. Little serendipitous moments that completely changed the course of his life.

He started to play, and he liked it. “It was an outlet,” he explains. “Still is an outlet. And, you know, my brother, who’s 13 months younger than me, is very much into sports. And that was his outlet. And I think when kids find their outlet, they’ve found their voice, so they stick to it, get enamored by it. So yeah, I was completely enamored by this new outlet of classical music.”

His mother took notice and decided to have Jonathon audition for the Charleston County School of the Arts at the age of 11. He admits that the audition went badly. He wasn’t really an advanced player, he just loved making music.

“The cello was bigger than he was,” chuckles Sarah Fitzgerald, the now-retired orchestra director of the school.

“He was so precious. And I can’t say that his audition was stellar. But we were like, this guy’s got something. We’re not real sure what it is, but it’s something.”

They added his name to the waitlist.

And then another one of those serendipitous things happened. A sixth grader dropped out of the program and Heyward got his slot. (In a further coincidence, that sixth grader, who joined the school the following year, would go on to become Heyward’s best man at his wedding.)

Heyward immediately loved the school. He felt like he was among his people.

“The school was a melting pot of different socio-economic backgrounds, religions, races, creeds,” he says. “But we were all interested in the arts. That was the link. I had friends who grew up in mansions. And it didn’t faze them one bit when they came to my house that I shared a small bedroom with my brother, and we slept on these tiny little cots. Because we all just loved music, it was our common ground. It taught me so much at such a young age about how we break barriers with the arts.”

Despite the slow start, he was getting better at the cello every day, and Fitzgerald, who remains close to Heyward and has watched his career take off with great pride, took notice.

“He was like a sponge,” she says. “I mean. . . he wanted to just soak up everything around him. He was always curious and always so appreciative of the opportunity—and he still is very appreciative. He’s just such a great guy.” She gets choked up for a second reflecting on her beloved pupil. “Anyway, I’m not gonna cry. . ."

Heyward tried his hand at conducting for the first time at the Charleston County School of the Arts and yes, it was the result of another bit of extraordinary happenstance.

There was a substitute teacher who didn’t know how to conduct. Names were put in a hat to determine which student would conduct that day. Heyward’s name was drawn. (You couldn’t make this sort of thing up.) He got to the podium, raised his hands over his head, and the orchestra sat up, in attention. Then he began to conduct—and they followed him, his emotions, his tempos. It was his first time experiencing the thrill of leading an ensemble.

He became obsessed, he says, not just with conducting, but with scores—those giant books containing all the different orchestral parts. “The idea that you can make one sound out of so many different voices, that’s still something that really inspires me today,” he explains. “And I think it’s what makes classical music so powerful, actually.” He would go home and actually read scores, for fun.

“I was a giant dweeb,” he admits. And he kept getting better.

Eventually, he attended the Boston Conservatory at Berklee, as a cellist. He told his professor that what he really wanted to do was conduct.

By junior year, he was named the assistant conductor of the school’s opera department.

After Boston, in 2014 he was accepted to the Royal Academy of Music to study conducting, which changed everything.

et's start with his voice. When you hear Charleston County Art School’s Sarah Fitzgerald speak, you’re struck by how Southern she sounds—it’s a voice that evokes sweet tea and grits and a rocking chair on a porch.

Heyward sounds nothing like that. He has a clipped, quasi-British accent—he sounds positively posh. It’s the result of years studying and conducting in London and living with his now-wife, Millie Aylward, who is English.

“I’ve been in London for 10 years,” he explains. “And my job is to listen. I think I just picked it up. I’m a bit of a chameleon, actually.”

(Aylward agrees with this. “When he comes back from Germany, he’ll have a slight German twinge,” she says.)

It makes sense that he would absorb accents differently from the rest of us. Accents have a certain music-like cadence—and Heyward’s life is music.

He met Aylward his first year at the Royal Academy. She was also doing her postgrad, studying the clarinet. (A soprano, she has since switched to studying and performing voice.)

She attended an orchestral workshop that Heyward conducted and was instantly smitten.

“I know it sounds cliché, but he popped onto the podium, and I just thought, ‘Oh great. I’m marrying him.’” She relays this in a matter-of-fact voice, like it was some official bit of business that she had settled. “And then we didn’t talk for the next two years!”

She says what initially drew her to Heyward was the sense of serenity about him. “He has this inner calm,” she explains. “And also, he felt very familiar to me, even though we had just met.”

Heyward had spotted her in the orchestra and felt similar stirrings. But both were too busy to pursue a relationship. (He also insists she gave him zero signs.) Then a few months before graduation, he got “the guts” to ask her out. They began dating, as though it had been preordained. They got married last May.

The proposal, as Aylward describes it, was very romantic and bit farcical—like something out of a Hugh Grant rom-com.

It was Christmas morning. One thing you have to know about Aylward is that she loves Christmas. Her job, which she took quite seriously, was to make Brussels sprouts for the family Christmas supper. The timing was essential—“nobody likes soggy Brussels sprouts,” Aylward says. But the previous night, Heyward insisted on going for a morning walk and wouldn’t take no for an answer. She indulged him, but said they would have to get up very early to do it.

“It was very cold, very dark, like very miserable,” she says. “We were walking in our wellies, the sun hadn’t even begun to rise yet. And we got into the middle of this field that’s near where my parents live. And then the sun started to rise. And it was really beautiful.”

At that point, she was ready to turn around. “He was dawdling,” she remembers. “I was like, ‘Jonathon, I’ve come for your walk, we’ve got to speed this up!’ And he started being really mushy and did this whole speech. And then he got down on one knee. And I was like, ‘Oh my God!,’” She laughs remembering it. “I had no idea what was going on.” As for the Brussels sprouts?

“I gave them to my sister [to make]. I said, ‘I just got engaged. You can handle the Brussels sprouts.’”

After the Royal Academy, Heyward’s career took off rapidly. While in school, he had won the Besançon, a prestigious conducting competition. It set him on his path—a job as conductor of the Hallé Youth Orchestra and assistant conductor of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester, England; an appointment as chief conductor of the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie.

One day, while still with the Hallé, he forgot his shoes before an educational gig in front of Manchester school children. He was in a panic, but his supervisor told him it was too late to go home and get proper shoes—he’d have to conduct with his sneaks on. Later, he received feedback from the students on little cards, and “an overwhelming number of them said that what they enjoyed most about the concert was my red Converse.”

It was embarrassing, but it taught him a valuable lesson: “Suddenly, they related to me, and they related more to classical music, just because I was wearing Chuck Taylors. And I thought, how powerful is that? It was a way to break that barrier, that wall, which is so important to me. It wasn’t on purpose, it was just another serendipitous moment, but it stuck.”

It also earned him a new nickname, the Converse Conductor, which he still uses as his Instagram handle.

Heyward was young, he was hip, he was talented, and his star was on the rise. And then the BSO came calling.

t's a wonderful thing to watch Jonathon Heyward conduct. He doesn’t just dance on the podium, as many conductors do. But he seems to use his whole body, particularly his long, graceful hands and arms, in such a way as to make geometric shapes. There are circles and semicircles, arcs, and angles—it’s as though Bob Fosse himself had choreographed his movements. When he conducts, he tends to wear close-cropped Nehru-style jackets with sleeves that are a little too short, so you can see the top of his white dress shirt and not only his hands but his dancing wrists.

He has a musicality and a joie de vivre that oozes out of him. It’s noticed by orchestras and audiences alike.

It was certainly noticed by the hiring committee at the BSO. In 2021, artistic director Marin Alsop had stepped down after a 14-year tenure and the orchestra was looking for her successor. While her years with the orchestra—which included a Grammy nomination for the orchestra’s performance of Bernstein’s Mass, a performance at New York’s Carnegie Hall, and a slew of community outreach initiatives, including OrchKids and the BSO Academy—could only be described as a success, her initial hiring had been somewhat controversial. The musicians felt they hadn’t been sufficiently consulted during the hiring process, which led to a tense start for the new maestra.

Current BSO executive director Mark Hanson was determined to do it right this time. He assembled a hiring committee that included several musicians, board members, staff members, and even some members of the community. And after each auditioning conductor rehearsed and performed with the orchestra, members were asked to fill out a card assessing their abilities. Hanson put a lot of weight on those assessments.

The first time Heyward conducted the BSO, in March of 2022, he was tackling the tricky and rarely played Shostakovich 15th Symphony. He knew it was an audition to be the permanent maestro. And it was like being thrown into the deep end.

“I had never conducted it,” says Heyward. “And they had never played it. It could’ve gone wrong very quickly.” Instead, the performance was a rousing success—he got several curtain calls. And what’s more, he and the orchestra developed an immediate simpatico.

“From the start of the rehearsal, he was doing all of the tangible and intangible things that you want from a conductor,” says BSO first violinist Greg Mulligan, who was a member of the search committee. “You want a traffic cop at times, but only when you need a traffic cop. The rest of the time you want inspiration. And he was giving us that.”

Associate principal second violinist Ivan Stefanovic was similarly inspired. “At the Meyerhoff, it’s very easy to play with a full sound all the time and to forget what a true pianissimo is,” he explains. “Because it’s a loud hall, you have to try harder to play with an intimate sound. And my God, in the first rehearsal already, Jonathon was having us play some dynamics and colors that I had not heard in a while. It was remarkable.”

(Heyward’s contrasting dynamics seem to be something of a specialty. In a Washington Post review of a May concert, critic Michael Andor Brodeur wrote, “Heyward’s way of bringing out the softer side of this orchestra is what intrigues me most about his forthcoming tenure.”)

The response was so overwhelmingly positive, BSO officials invited Heyward back a month later, in late April of 2022, this time for a benefit concert for Ukraine. Once again, crowds were euphoric.

The committee was getting to know Heyward better, too, seeing not just his talent and his rapport with the orchestra, but his bone-deep belief in programs like OrchKids and his commitment to making the Meyerhoff a more welcoming, inclusive space. Even as a guest conductor, he was keen on exploring Baltimore—the Lexington Market, Mt. Vernon Place—and interacting with its people.

“He’s an ideal music director for an organization that is very much about evolving as an institution to ensure that we not only continue to inspire and engage longtime audience members, but find the next generation of audience members,” says Hanson.

The committee knew that if they didn’t act quickly, Heyward would likely be snatched up by another orchestra. (Case in point, in the last year alone, he was named “One to Watch” on the Bloomberg 50 list and was appointed summer director of New York’s Mostly Mozart festival.)

That July, Heyward was formally announced as the BSO’s new maestro.

eyward doesn't have a lot of hobbies—remember, this is a man who likes to read orchestral scores for fun.

He is, however, a hardcore espresso drinker. Aylsworth says he always has a collection of coffee-stained demitasse cups that pile up on his nightstand and desk in Folkestone, the southeast England town where the couple has a house. This is mostly because he’s gotten so engrossed in whatever musical passage he’s studying, he forgets to take them to the sink. Otherwise, he’s good at doing his share of chores around the house. “He’s a modern man,” she says.

To that end, Heyward has recently embarked on a new hobby, one that engages all of his senses—he’s taken up flying.

“For my birthday last year, my darling wife got me my first flying lesson,” Heyward says. “And I’ve been hooked since. It’s something completely different. And I think it’s the only time where music isn’t playing in my brain, because I have to focus so much. I love it.”

Aylsworth isn’t too worried about the potential danger of her husband’s new pastime—she says it’s nice for him to have a pursuit that’s completely separate from music. “You have to have time away from music in order to bring something back into the music,” she explains. For now, she’s still in England, studying voice, but she’ll hopefully move to Baltimore later this month—at least part time; Heyward says they’re looking to find a loft-style apartment, possibly in Canton or Fells Point.

Of course, the life of a conductor, even one with a permanent appointment, is peripatetic. There are guest conducting jobs, world tours, and summer festivals. Aylsworth, who describes the whirlwind of the past two years—COVID, followed by Heyward’s rapid hiring—as “surreal,” says she likes to travel with her husband whenever possible. As a singer, she brings her “instrument” wherever she goes. And Heyward says he never would’ve accepted the position without her blessing. Luckily, she is as bullish on Baltimore as he is. “The people are just so unbelievably friendly,” she gushes.

At 31, Heyward will be one of the youngest music directors in the country. This gives him lots of advantages— an exuberance, an energy, even a touch of irreverence.

And we’ve already seen his cheeky personality come out on stage.

During a performance of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in May (he conducted a few concerts this spring, in anticipation of his full-time appointment), the crowd got a little too excited and applauded after the first movement. This is a classical music no-no, but exactly the kind of thing Heyward wants to encourage—why shouldn’t they applaud in the middle of the piece? But the cheering went on a bit too long. Heyward swiveled on the podium and said, “Wait, there’s more.”

It happened again, later that month, after the prelude to Xavier Foley’s “Soul Bass.” This time, Heyward turned to the crowd and quipped, “It gets better.”

These incidents demonstrated a couple of things: One, that Heyward is comfortable breaking the “fourth wall” of classical music—he wants it to be fun, not this rarefied, intimidating thing. He also is clearly bringing new fans to the Meyerhoff, people who are perhaps not steeped in classical protocol, who don’t sit on their hands between movements and try so hard not to cough it results in a coughing fit.

On the other hand, being a young conductor is not without its challenges. For one thing, he’s learning a lot of these massive works of repertoire for the first time. How does he gain the respect of seasoned musicians who have possibly played the piece dozens, if not hundreds of times? As always, it comes down to the music.

“What I learned the most, as I explore life as a young conductor, is that if you have a common ground of just purely making music and collaborating, people will, nine times out of 10, be on your side,” Heyward says. “If you show the passion and love for the art form, that can be your driving force.”

That love of music is the thing that has propelled him throughout his career. He never really needed to “see it to be it,” because he was always following his own calling, his own muse. He never gave much thought to his age, or the color of his skin, or his relative inexperience. It was always about making music.

But he’ll never forget how it all started. At a public-school music program, where he stood in a shorter line and picked the cello, and at a school for the arts, where he first found his outlet—and his tribe.

The week he was in town for that Ukraine benefit—mind you, this was before he was named music director—he went to visit the OrchKids.

“He spent like three hours actually going around to two of our main sites and talking to all the students and teachers,” says Nick Skinner, the OrchKids VP. “And it was just such a beautiful experience to have someone so willing to give his time for something he’s so passionate about. And the students connected to him so well, because this was someone who had been on a similar journey as some of them. I remember thinking, ‘I hope [the BSO] hires him, because he will be so good for us.’”

It’s no secret that attendance is down at symphony halls across the country, as orchestras struggle to attract young and diverse audiences.

This is why Heyward’s appointment is so crucial. He wants to bring new people into the Meyerhoff. He wants to strip orchestral performance of its perceived stuffiness. He wants everyone, as he told those OrchKids players, to feel like this is their home. And he wants to be a role model so that young people, especially young Black people, can “see themselves on that stage.”

“Because if a 10-year-old boy from Charleston, South Carolina, can be enamored by this music, I think anyone can,” he says. “I really believe that.”