Arts & Culture

Worth Her

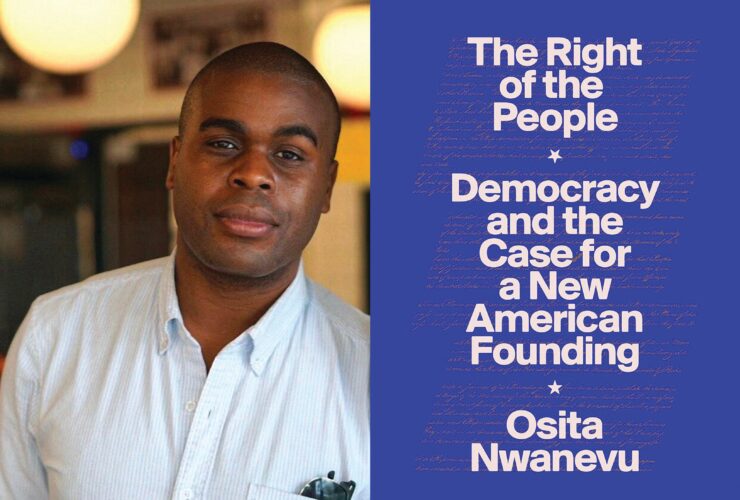

With her salt box project, Juliet Ames launches a public art movement.

By Jane Marion

Photography by Christopher Myers

Lettering by Luke Lucas

S THE HOLIDAY SEASON rapidly approaches, Juliet Ames’ Mill Centre art studio is a riot of creativity. On one side, there’s her “salt box lounge,” with its cozy emerald-green sofa, a wall of framed photos and mementos—a sort of visual résumé of her accomplishments (her appearance on The Martha Stewart Show, a Christmas card from filmmaker John Waters)—and a pegboard with tools of her trade: a hammer, tile snips, some scissors, a pair of pliers, and various hex wrenches, plus rolls of vinyl in every hue of the rainbow.

On the other side of the studio, there are bins upon bins filled with broken shards of china and wire shelving units swelling with stacks of patterned plates—all awaiting new life as some sort of necklace, cuff link, or earring (and once even a pair of porcelain pasties for a breast cancer awareness benefit.) There’s also ceramic salt box mugs and salt box branded ties and bowties scattered around the room—available not just around the holidays but any time of year.

In the center of the room is her so-called “big ass table,” an oversized wooden workbench where Ames toils most mornings making art of one kind or another, be it salt box panels or filling orders for her one-of-a-kind jewelry.

“I’m an artist who can’t paint or draw,” chuckles the 44-year-old Ames, best known for her The Broken Plate jewelry company—and more recently for her fan-favorite salt box art. “So, this,” she says with a sweep of her arm, “is my solution.”

Whatever she lacks in fine-art abilities, she more than makes up for with her endless imagination for taking everyday objects and transforming them into unique works of art.

Opening spread: Ames stands outside

the salt box storage

facility at Baltimore City’s

Department of

Transportation.

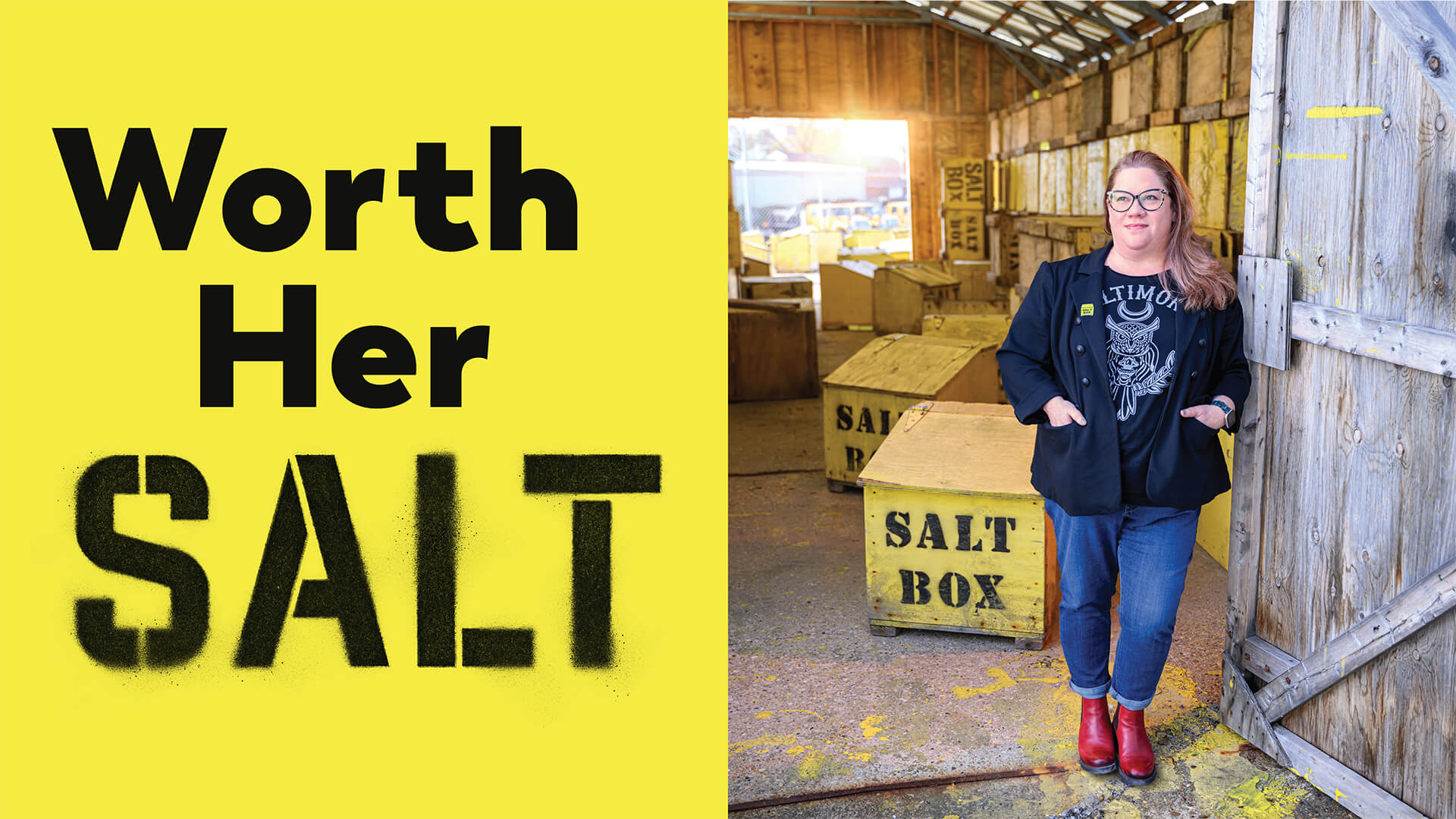

Ames works on a salt

box design in her

studio.

MES, A BALTIMORE NATIVE, has had many chapters in her decades as an artist, earning some early acclaim for her “broken plate” creations. But it was her salt box story—one that started with the promise of snow and a fun art project—that got her national attention. “I grew up in a salt box-rich neighborhood,” she says, of the mostly city-issued boxes containing salt to melt snow. “I remember seeing them and thinking that snow days were coming, and I was excited by that. I just always thought they were cute and the yellow would pop out at me—I noticed them all around Baltimore.”

As an adult, she never lost her interest in them, observing that while the boxes are seemingly the same, they are all a bit different. (For example, some simply say “Salt,” others say “Salt Box,” and others say nothing at all.) “They’re like snowflakes,” she says, “no two are the same. I would take note of them and whatever stencil they used. If they don’t use a stencil, they look naked to me, and some have just fallen into a general level of disrepair.”

Salt Box art dedicated to Baltimore magazine owner Steve Geppi.

In December 2020, when she happened to see a nonstenciled salt box in her Lake Walker neighborhood, it gave her the idea to make large blue-and-white china letters spelling out the words “salt box.” With snow in the forecast, she glued them to a panel of plywood to apply to the face of a box simply for the sake of photographing it. But after making the panel, she got a case of cold feet. “I made it just to photograph, but I didn’t put it up because I didn’t want to get in trouble,” she recalls.

Soon after, while driving to her studio at the height of the pandemic, she had a change of heart. Ames spotted an old beaten-looking box at the corner of Roland Avenue and West 36th Street. “There were no letters on it,” says Ames, “and I’m like, ‘Well, I guess that’s the one.’ I called my partner, Jason, and I’m like, ‘I found the one. We’re doing it tomorrow.’”

The next day, at 9 a.m. on Dec. 13, Ames drilled four screws into the box, taking care not to damage city property. “I brought my paint, too, I really wanted to make the box look fresh,” she says, “but it rained the night before and I couldn’t paint it. Still, I was able to put the cover on it and make it pretty.” Her heart was pounding, as she and Jason drove away.

Her timing was perfect. “There was snow in the forecast for two days later,” she says. “And with snow coming, I would get to take the snow-day photo I’d been hoping for. I thought it would be a fun pick-me-up for the neighborhood.”

Ames in her Mill Centre studio.

And although she was concerned about the idea of defacing public property, the self-professed rule follower sent out a tongue-in-cheek tweet with a photo of her installation: It looks like **someone** vandalized a salt box in the night. The nerve! “Clearly, it was mine, because of the china letters,” she says.

The reaction was immediate. “Baltimore Twitter was having fun with it,” Ames recalls, “but six hours after I tweeted it, I heard from the Department of Transportation, whom I did not tag. The tweet said something like: ‘Someone had a little fun with one of our salt boxes. We love it and we challenge other artists to do the same.’”

Ames was overwhelmed by the reaction. “I couldn’t have thought of a better outcome—it was supposed to be one and done,” she says. And yes, she did return to the scene of the “crime” to photograph the box in the snow. “I was screaming, ‘Holy shit! I pulled this off!’”

breaking

plates.

THE SALT BOXES, most of them mixed with sand and salt, have been installed since the late ’50s on streets, sidewalks, and parking lots deemed too difficult to plow. Amazingly, while now a symbol of our city as synonymous with Baltimore as Bergers and Bohs, these utilitarian boxes—some 1,000 or so scattered mostly throughout the city, and the only ones still in use in the U.S.—are something that prior to the pandemic few of us even noticed. Hampden resident Robert Atkinson was one exception. Atkinson, now Ames’ salt box partner-in-crime—was equally obsessed, photographing area boxes and starting a dedicated salt box Instagram account (@baltimore.saltbox) as far back as 2018, before Ames was out there pursuing her passion project.

Prior to meeting Ames, Atkinson had also created a Google map of the box sites, which now serves as an ad-hoc guide for anyone who wants to view them—or decorate one of their own. “It was weird that these two different people came at them to raise their profile,” says Atkinson, aka “Salt Box Bob.” “I got obsessed with them and Juliet, who was a total stranger at the time, started doing what she does, and it was like, ‘Oh my god, it all goes together’—and suddenly they had prominence.”

Ames’ first salt box was created using her trusty broken-china method. From there, she got even more creative—utilizing stencils, vinyl, and other materials. While she can’t say for sure how many salt boxes she’s decorated—her best guess is 125—the true impact of Ames’ public works project has been far-reaching. Her salt box art, made at her own expense and much of it Baltimore-themed, including a googly-eyed Mr. Trash Wheel, a bag of Utz potato chips, a replica of an Old Bay tin, and nods to local legends like writer Laura Lippman and chanteuse Billie Holiday, led to a visit from Good Morning America to her Hampden studio, and a glowing piece in The New Yorker, which deemed her work “a symbol of civic pride.”

She has also inspired countless artists—professional and novice—to contribute their own panels. (And on her website even shares her own process and the exact right shade of yellow to use.)

Thanks to thousands of fans and followers, Ames has gotten plenty of local love, too. In fact, some of her biggest boosters have been Charm City celebrities who’ve inspired her panels, including MacArthur fellow Joyce Scott (who influenced Ames to do a beaded panel in homage to the artist’s intricate bead-based work) and city resident John Waters, the subject of several boxes, who told The New Yorker, “Baltimore salt boxes went from being the most ignored city property to Banksy-bait in one single good idea,” referencing the famed street artist. As if that’s not enough, the salt box found its way onto a recent Ravens holiday card, an Otterbein commemorative tin, and in Fluid Movement’s latest summer show, “Sinkholes, Sewers & Streams.”

All of this has led her to an inevitable conclusion—“She’s an icon now,” says Ames of the boxes.

The same can be said of Ames.

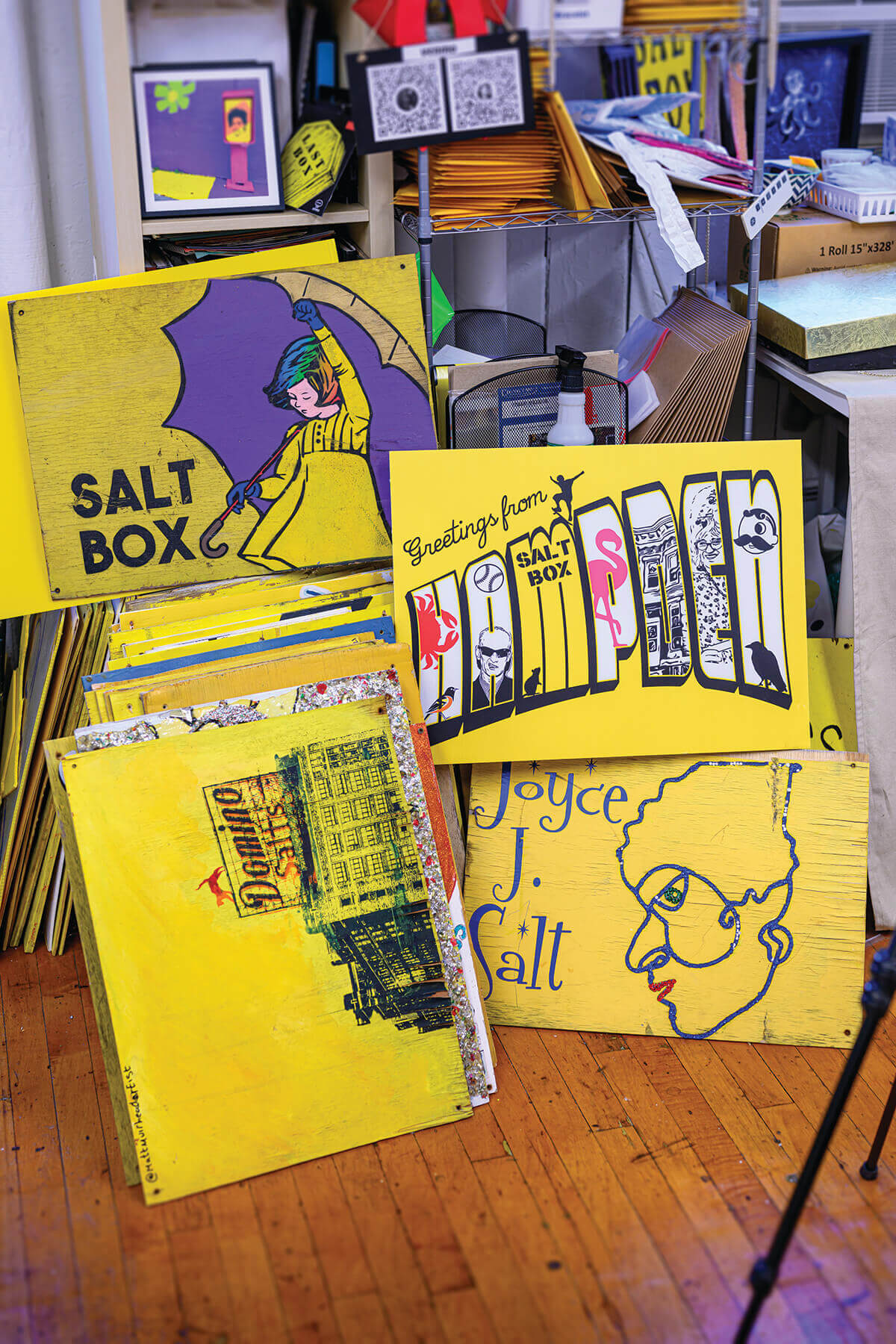

Some

salt box greatest

hits, including the

Domino “Salts” sign.

ROWING UP IN BALTIMORE with a sister eight years her senior and an ailing father, Ames largely spent time alone in her room playing with Play-Doh and Legos. “My dad, Delano, had scarlet fever when he was a kid, so he had health problems his whole life. The story is that I was made because it was a reward for him doing his physical therapy,” she says with trademark humor.

Despite the difficulties, the family learned to laugh. “We used comedy as a crutch,” says Ames, whose dad died when she was four. “My mom, Joan, was pretty witty.” One of her father’s legacies is that he passed on his interest in working with his hands. “There was a lot of tinkering with things at home,” she recalls. “My dad was pretty crafty. He liked to take things apart just to see how they worked. That’s the crux of it all for me—I like to disassemble things and put things back together again.”

Ames studied photography at the Community College of Baltimore City in the late ’90s. When she transferred to Towson University to earn a four-year degree, with film photography on the wane, she switched her major to interdisciplinary craft, studying stained glassmaking and metal smithing, among other mediums. “My teachers tried to guide me to stay in metal smithing,” she says. “I saw a vision of me working at Zales and that didn’t seem very fun. I just couldn’t imagine making diamond wedding bands all day.”

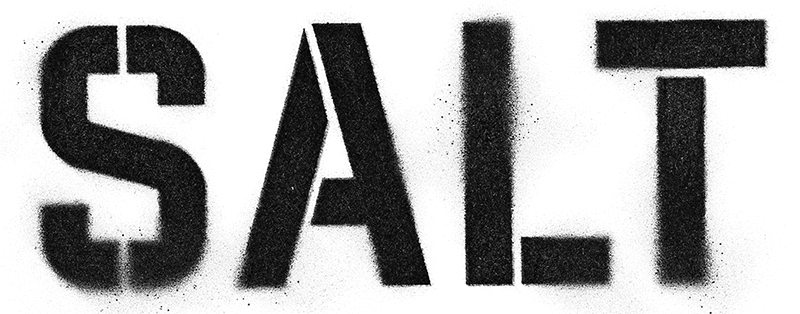

The “exact right” yellow used to paint the salt boxes.

After graduating from Towson in 2005, she worked a desk job at the Howard County Arts Council. “One whole hallway was artists with studios, and I’d see them coming in and out,” she says. “And I was like, ‘Oh, man, I wish I could do that.’”

Before long, she was.

At home, after making a mosaic on her mailbox using shards from plates purchased at Goodwill, she crafted several necklaces with the leftover glass pieces. When she wore one to work, the other artists admired it and encouraged her to sell her creations at the on-site gift shop. By 2006, The Broken Plate (and nine months later her son, Nolan) was born.

Initially, Ames bought—and broke—salvaged plates from thrift stores, antique shops, and department stores to “lovingly” smash into smithereens and repurpose into delicate pieces of jewelry. But as her work got out into the world, customers sought custom keepsakes using their own china, including scores of clients with grandma’s chipped heirloom plates. In one instance, Ames repurposed a bottle of bourbon. “It was a bottle these friends had shared. And when one of them passed away, they sent it to me to break and make a set of necklaces,” she says. On another occasion she made jewelry from broken bits of a plate from an ancient Jewish tenaim betrothal ceremony in which, historically, a plate is broken to symbolize the acceptance of the conditions of the engagement. “That’s when it clicked for me that there’s something to this whole sentimental thing,” she says. “I realized there was a deeper meaning to my job and that I had more of a purpose than just making goofy necklaces.”

While Ames sells most of her work online, her objects have appeared in museum gift shops and historical societies, including the Smithsonian, The Walters, and the Onondaga Historical Association in upstate New York, which commissioned her to make pieces from the late Barbara Walters’ elegant collection of Syracuse china. A porcelain bow tie she made once graced the neck of The Tonight Show bandleader and Roots drummer Questlove (“I sent it to 30 Rock because I know he has a bow tie collection,” she says), and her necklaces have been worn by Rachael Ray on the Food Network. Closer to home, WBAL’s Jennifer Franciotti has an original Ravens necklace she wears on game day as a good-luck charm.

While Ames’ jewelry has taken on a life of its own, much like her salt boxes, it’s the idea of photographing the image that inspires her. “I’m still a photographer,” says Ames. “It’s not about the breaking of things, but the final result. I make a lot of pretty things because I like styling photos.

The same can be said of her photogenic salt boxes, aka her “little yellow friends,” which instantly brighten the mood of every neighborhood they occupy, whether it’s a salt box with literary legend Edgar Allan Poe across the street from the Enoch Pratt Free Library at West Franklin and Cathedral streets, the Morton Salt Girl (whom Ames also has tattooed on her thigh) at Walker and Weidner avenues in Lake Walker, or Baltimore jazz musician Cab Calloway at Biddle and North Charles Street in Mid-Town Belvedere.

“How can you drive by a salt box and not smile looking at it?” says WJZ-TV’s Marty Bass, himself the subject of a salt box and something of an Ames superfan. “You’ve probably been looking at these things forever thinking, ‘Why is that there? I would never use that and probably I never will.’ But now you go, ‘Wow, there’s Divine holding a saltshaker or Bob Turk or Jamie Costello.’ It’s a fascinating thing—Juliet has given kitsch fresh air and people are embracing salt box culture.”

Unloading

boxes at the DOT.

N AN EARLY FALL DAY, Ames is amping up her jewelry production to sell wholesale for the holiday season, while also readying for her fourth season of salt boxes and what she lovingly calls “Descension Day,” aka November 15, when she drives around town in her blue Mazda installing new panels on boxes. She no longer has to worry about the Baltimore City Department of Transportation (DOT) catching her in the act. They are fully onboard with the project. (In fact, she visits the people who make the salt boxes somewhat regularly and even bakes them muffins.) On April 15 of each year—yes, Ames calls it “Ascension Day”—they not only collect all the salt boxes for storage in a facility on Pulaski Highway but issue a separate truck to take down the art panels, assiduously writing the names of the streets where they were removed on the back for easy reinstallation. (The panels themselves will be stored at Ames’ studio after she and Atkinson collect them from the DOT warehouse.)

A pile of BIG FUN salt box pins, inspired by a Baltimore-themed episode of The Cosby Show.

Her latest salt box design is a portrait of Herman Williams Jr. While Ames had originally set out to celebrate his son, talk-show host Montel Williams, research led her to discover that the older Williams was not only the first African-American fire chief in Baltimore City, but he oversaw the city’s giveaway of 70,000 smoke detectors during his 26-year tenure with the Baltimore City Fire Department. “Montel Williams was a talk-show host,” says Ames, “but his father was a hero.”

A few weeks earlier, Ames drove down York Road near Radnor-Winston to install an Adam Jones panel just 10 days or so before the Orioles outfielder’s retirement. The salt box sits on the edge of a parking lot of a Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen, a chain that Jones frequents. The new panel is replacing her homage to The French Connection (a reference to the Gene Hackman character named “Popeye” Doyle). “I’m not into sports,” says Ames, “but Adam is a great character.”

Reflecting on the last few years, Ames marvels at the fans she has amassed, and all her whimsical art project has brought her. You might say that the shy artist identifies with being transformed. While reimagining the salt box, Ames has come out of her own shell, sharing her work, along with Atkinson, at the American Visionary Art Museum and appearing on Good Morning America and regular segments on WJZ with Marty Bass, who dressed as a salt box last Halloween.

With some 120 artists strong, the salt box project has been a huge hit because Ames is so clearly committed to her beloved hometown. “I don’t think I could do this anywhere else because we all celebrate our weirdness here,” she says. “I’m shy but I can express myself in this way and people laugh at it rather than picking on me for it.”

As for future projects, Ames has been thinking about making china pocket squares (“Pocket squares could use help,” she says) or designing a line of china or writing a book about her salt box art. “I’m not sure what’s next but until then, I’ll be breaking plates and making salt boxes,” says Ames, who has also used vintage area phone booths as her canvas.

The one plan she doesn’t have is to move away from her beloved Baltimore.

“I can’t imagine living anywhere else,” she says. “When I was 20, I drove from San Francisco down to L.A. and then through the middle of the country, thinking I’d find a place I’d want to live more than Baltimore. But I really just missed Baltimore the whole time—and as soon as I got back, I found an apartment and stayed put. The people are amazing, the food is good, and there’s lots of cool stuff to look at.” She pauses, and smiles. “And I like things that are a little bit broken, so it’s perfect.”