Kwame Kwei-Armah and Lawrence Gilliard Jr.

The Center Stage artistic director and The Wire star discuss the HBO classic, The Baltimore Unrest, and the beauty of getting naked.

By Lydia Woolever & Gabriella Souza

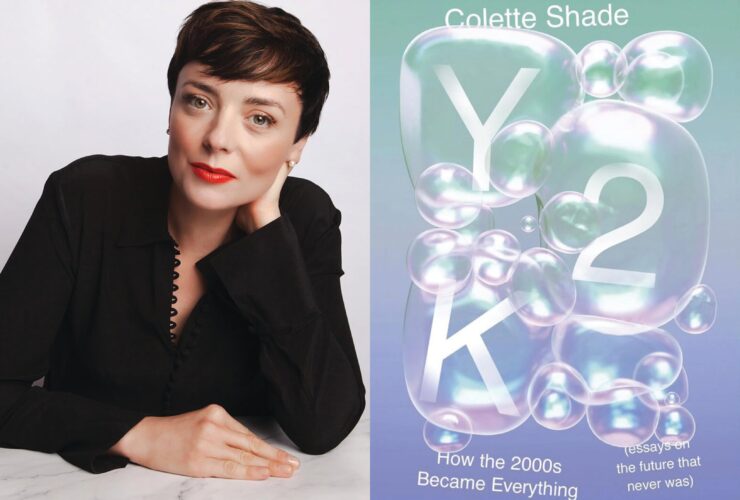

Kwame Kwei-Armah and Lawrence Gilliard Jr. at Center Stage in May.—Photography by Christopher Myers

You probably recognize the man on the right—Lawrence Gilliard Jr., the American actor behind the iconic role of D’Angelo Barksdale on The Wire (as well as Bob Stookey on The Walking Dead). But you might not know the man to his left, though you should. Kwame Kwei-Armah is the creative force behind Center Stage plays such as One Night in Miami and Amadeus, which he directed, and Marley, which he also wrote, as well as an award-winning playwright, actor, and fabulously accented Brit. In May, the two sat down to talk shop outside the Marley set.

Kwame Kwei-Armah: I didn’t really watch The Wire the first time, but when I got the job [at Center Stage], I did series one through five in, like, two days.

Lawrence Gilliard Jr.: It’s that kind of show.

KKA: I’ve just got to tell you, man: You were magnificent. What does it feel like to be defined by such a fantastic performance and iconic piece of television? Is it a weight on your shoulders?

LGJ: Not at all. It was a blessing to be a part of. I spent 10 years in Baltimore. I grew up where all that was happening. I played little league football in those high-rises. So it was very close and personal to me. I read [the script] like, ‘Oh my God, I know this street, I know this neighborhood, I know these people. I gotta get this role.’ I knew guys like [D’Angelo], so I could tap into it. We didn’t know it was going to be so special. I just wanted to be as real, authentic, and bring as much truth as I could.

KKA: It showed the harsh side of particular areas in Baltimore. How did you feel about that? Because for a long while, probably up until the uprising, Baltimore was kind of defined through the lens of The Wire.

LGJ: Growing up, I remember Baltimore [with] vibrant communities. I went to my neighborhood Boys & Girls Club and we had recreational centers. We would go to different neighborhoods to play other teams. [But] coming back to shoot The Wire and seeing what the city had become, it was hard. I give David Simon all the praise because he was telling these stories and showing it to the world as it was happening. I don’t know if it had as much of an effect as [we] hoped; but sometimes it takes something, like the rioting [to open people’s eyes]. When it’s on the news, you see this isn’t entertainment. This is real.

KKA: We were in tech rehearsal during that time, due to be working 10 ’til midnight. That’s when you really define the work, so once the curfew came down, we lost days. I think there’s a Chinese proverb that says, ‘May you live in interesting times.’ I happen to have lived in a number of cities amidst riots and disturbances—in my native Britain, in London, and growing up in Southall. It was interesting to move to a new city and call this my home, and see it amid the pains of civil disturbance.

LGJ: Were you a tough kid?

KKA: I certainly wasn’t a tough kid, though I lived in tough times, without a shadow of a doubt. The dominant white culture at the time was skinheads, so I remember as a kid, at any point, anyone in your family could be stabbed, jumped, killed.

LGJ: How much more brutal is actually stabbing someone, as opposed to shooting someone.

KKA: The environment was relatively hard, but I was fortunate because I came from a magnificently loving home—this brilliant sanctuary of joy, laughter, political debate, and religious exchange. My childhood was rather wonderful, I think. I had a great time in school, which was a little like the one your daughter goes to.

LGJ: Baltimore School for the Arts. That’s my alma mater.

“When it’s on the news, you see this isn’t entertainment. This is real.”

KKA: That environment is fraught with competition and ambition.

LGJ: All the good things you need at that age.

KKA: It really helps you not go off the golden path because you go, ‘Oh, if I get arrested when my mates are going stealing then I won’t be able to be part of the school show, and then I won’t be able to graduate, and I won’t be able to be the star I wanted to be.’

LGJ: I had a similar experience. My mom did an amazing job sheltering me from everything that was going on at that time, with Reaganomics and the crack epidemic. I’m just blessed that I got into [BSA]. How did you find the theater?

KKA: Theater kind of found me as an actor. I was about 18 and a friend saw an advert in the back of our trade paper that wanted a tall, skinny, black man who could sing. At the time, I could, so I went to the audition and got the job. It was a tremendous play because it was about the issues facing Britain in the 1980s, and at the end of every show there would be discussions with the audience. I was like, this is some deep shit. Not only am I acting but I’m able to discuss things that matter. It really set the trajectory for my life. . . . Theater was not just my love, but the thing that fulfilled me. . . . What’s it like being a recognized actor in America right now?

LGJ: It is . . . just weird, dude. I get a lot of people who come up and go, ‘D’Angelo!’ or ‘Oh my god, it’s Bob!’ but [sometimes] people come up and say, ‘Lawrence.’ It’s a bit surreal, but it’s really cool, because it just means people are enjoying what you do. You put a lot of effort and hard work and years into it.

KKA: What’s your work ethic? People think it’s a couple of TV hits and then it all just rolls in.

LGJ: As you know, that’s not how it always is. Everything I’ve learned about work ethic, I learned from the BSA. I was a musician. My clarinet professor, Bill Blayney, and the school showed me that hard work pays off.

KKA: But what happens when you do the work and you don’t see the result immediately?

LGJ: That’s why, of all the mediums, theater terrifies me the most. Because you do the work and then it’s closing night and you go, ‘Oh, damn it, that’s what that [missing piece] was.’ Another thing that terrifies me is you do a lot of work at the theater. In front of everyone, you’re learning, you’re discovering.

KKA: You’re making your mistakes.

LGJ: In front of everyone! I like to do my homework at home.

KKA: The first couple of times you make your mistakes in front of everyone, you’re really paranoid. Then you’re kind of used to failing, and you fail up.

LGJ: And that’s what makes you a family. You’ve seen everyone go through their failing, and you share in it.

KKA: Being an actor is like standing in front of someone you desire, stripping yourself naked, and saying, ‘Do you like what you see?’ Every applause or laughter puts a bit of clothes over your exposed parts. By the end, you’ve got a fur coat on and you’re sweating. That’s why I respect actors so much. [I admire] those who have to take the tough tumbles. A friend of mine said the other day, ‘I audition for a living.’

LGJ: That’s what it feels like sometimes.

KKA: The American actor is outstanding in that, in a way I didn’t see in Britain.

Lawrence Gilliard Jr. on getting his role in The Wire

LGJ: It’s a hustle man.

KKA: What’s the dream for you? Or are we too long in the tooth for dreams?

LGJ: I’ve always been a big dreamer. That’s what’s gotten me this far. Right now, my dreams are just keeping busy and working.

KKA: This could be a ludicrous question, but do you have a USP—a unique selling point?

LGJ: I don’t think there’s a ‘my thing’ that I apply. There are certain things that draw me as an actor. I like to play roles where we see a human being [try to] overcome some obstacle. Sometimes they make it. Sometimes they don’t. . . . I saw [your plays] One Night in Miami and Marley. I see a theme. Both deal with civil unrest and entertainers and how it affects them. Is this something that’s important to you?

KKA:

Here the thing: I’ve had the most magnificent season as I’ve danced with geniuses and heroes, from Mozart to Muhammad Ali. I think there is a real theme

with the things that fascinate me. . . . I love politics, I love the machinations of politics, but I also love the way human beings, and in particular

diasporic Africans, deal with their environment—[its] effect on one’s psyche, spirit, and soul. I think my work has been dominated by asking big social

questions. In a way, history, politics, and revolution—both with a small ‘r’ and big ‘R’—are themes I find fascinating, but they have to be through the

prism of entertainment. Theater, at its core, is a palace of entertainment and a palace of intellectual investigation.

Kwame Kwei-Armah and Lawrence Gilliard Jr. take a break from their discussion to post at Center Stage. —Photography by Christopher Myers

LGJ: Entertainers reach the masses.

KKA: Just think about The West Wing. Think about The Wire. These narratives ask fundamental questions through entertainment, but ask really deep questions of America. You know, post-Industrial America: What are we going to do about our cities? As human beings, what are we going to do about them? I’m blessed to be an artistic director where I can allow our audiences to dance with big existential questions.

LGJ: I read somewhere you said you are a theatrical practitioner, sometimes broadcaster, always father.

KKA: That’s my Twitter [profile].

LGJ: Do you have kids?

KKA: I do. I have four children and a grandchild.

LGJ: What! Dude.

KKA: Yeah, I’m a granddad, baby. Isn’t fatherhood beautiful?

LGJ: It is. But you seem like one of those cats who doesn’t sleep. How did you manage it all?

KKA: Family is everything to me. Thank God I’m living in this time of technology. I WhatsApp my kids. We follow each other on Snapchat. We Instagram, Skype, and FaceTime daily. It charges me. It gives me a sense of duty, a sense of who I am. I can’t remember myself before fatherhood. . . . When I juxtapose my children and time against each other, I stop thinking about how little we have. If there’s one thing I have a little control over, it’s time. So just sleep less, do things.

LGJ: When you look at your kids and how fast that happens, you’re right, it makes me want to go do something right now.

KKA: Let’s start a new play! Let’s write, right now! . . . We’re very fortunate to be people of our hue doing what we do—we’re very blessed, aren’t we? And there is an embedded insecurity in it. No one comes up to you and goes, ‘You are now retired. You’ll never act or direct again.’ . . . They don’t give a shit, and then it’s gone. I’m a little bit of an optimist, with a tinge of pessimism. So I say, as long as the sun is out, get naked.

Center Stage artistic director and Britain native Kwame Kwei-Armah tells The Wire actor Lawrence Gilliard Jr. the remarkable story of how he ended up in Baltimore.

LG: How’d you get from London to here?

KKA: In essence, I think the story goes that in 2001, I wrote my first play called A Bitter Herb about a young black boy who was killed in a racist murder and the effects it had on his family. After the show, an American critic came up to me and said I loved your play it reminds me of [famous American playwright] August Wilson. So I gave her the contents of my wallet [laughs] and dedicated 10 percent of my wages for the rest of my life, just in gratitude. And she said, ‘Did you know he’s got a new play? It’s about to open in [Washington] D.C.,’ and I said ‘Get out of here!’ It was King Hedley. I had a two-week break in filming, early into the days in 2001. I went on the computer and found that it was going to be at the Smithsonian and the Kennedy Center and I went to book my ticket. It took about 58 hours; it was dial-up. [Then] I wrote to August Wilson’s director Marion McClinton and I was like, ‘Hi, my name is Kwame Kwei-Armah and I would just like to sit at your table.’ I probably sent it to the Kennedy Center [instead, by accident] and it got lost.

And so I went to the play. And August Wilson was at the play, and he was my hero. I wanted to go up and be like, ‘Hi Mr. Wilson, you’re my hero,’ but then I thought, ‘No, you need to look intelligent.’ So I looked around and there was a book store and I thought, ‘That’s what I can do. I can buy one of his books and he can sign it and that’ll be great.’ So that’s what I do. I’m in line, I’m looking back, and he’s there. And then I’m the next person, I look, and he’s there. And then I buy the book, I look, and he’s gone.

LG: Oh no…

KKA: And I’m like, ‘Oh my god, he’s gone . . . ’ But he does this talk, and I never talk at public events, but I stood up and said, ‘Mr. Wilson, my name is Kwame Kwei-Armah. I came all the way from London, I traveled hundreds of miles to see you, and I just want you to know that I have to be the best fan in the room.’ I didn’t say that exactly, but that was the connotation. And he said, ‘Oh, you’re from London? I’m about to have a play on at the National Theater,’ and I said ‘So am I,’ and he said ‘Great, I’ll see you there then.’

But I wasn’t about to have a play at the National Theater. For some reason, it just came out. And I was just like ‘Oh shit . . .’ It wasn’t just like a mad crazy lie: I had been commissioned by the National Theater studio, and like one in 100 plays in the studio get from there to the big house. Anyways, [while I was in D.C.], I heard there was another play [nearby] I really wanted to see called Ragtime. And it was on in a town called Baltimore. I looked it up in the Internet and it was just like 30-odd miles away. I’d never heard of Baltimore before but I just went, ‘Alright, cool. I’ll go to Baltimore and then I’ll fly home.’

So I pulled up in Baltimore and I was so moved by meeting August that I wrote the first scenes of [the play] Elmina’s Kitchen, which I didn’t know was going to be Elmina’s Kitchen, in my hotel in Baltimore. I put that away and never looked at it again for two years and I went to see Ragtime at the Mechanic Theatre. I saw an advert for the Blacks in Wax Museum and went ‘Oh!’ So I hopped in a cab and went and saw that, and went, ‘Great,’ and then I flew home.

Like five years later, I’m in my agent’s office and a fax comes through and it’s Center Stage. ‘Dear Mr., my agent, we’d like to produce Elmina’s Kitchen next year and we’d like the director to be . . . Marion McClinton.’

LG: Wow . . .

KKA: Well, dog, I wish I still had the fax, because I took the fax and I cried. Because I was just like . . . Marion? August? I hadn’t even linked that it was Baltimore.

LG: You just saw: AMERICA.

KKA: Yeah! But mostly I just saw Marion, because when I saw Marion, I saw August. So I landed here [for the interview] and I went for a walk and I didn’t realize until I walked by the hotel, that, wait a minute, this is the hotel. This is where I wrote Elmina’s Kitchen . This is where I wrote the play that’s brought me right back to here.

So they produced my play, and when Irene [Lewis, former Center Stage director] was leaving, they asked me to throw my hat in the ring. Eighteen interviews later, I got the job. But the real story was this kismet, weird connection that brought me to Baltimore.

LG: Welcome back.

KKA: Thank you, sir.

LG: The very first play I ever saw was August Wilson’s Fences on Broadway with James Earl Jones. They were killing it. But Marion . . . He had a play called “Police Boys.” We did it at Playwrights Horizons [in New York] the first time. I was a member of that cast.

KKA: Get out of here.

LG: I played the Signifying Monkey. It was crazy.

KKA: We’re connected in many ways, sir.

-

Reverend Donté L. Hickman Sr. & David Warnock

-

David Simon & Laura Lippman

-

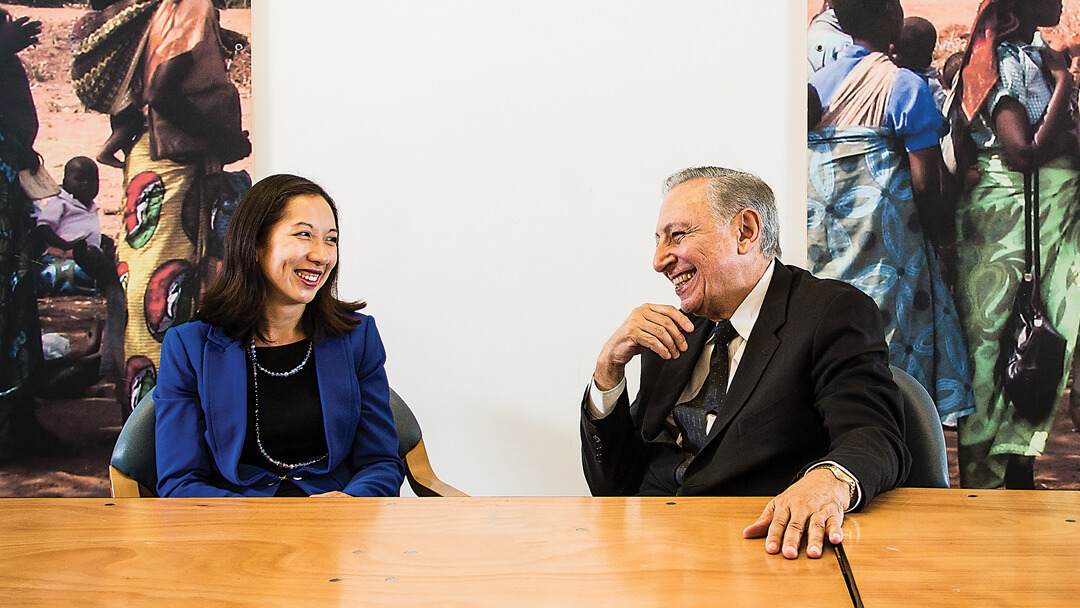

Dr. Leana Wen & Dr. Robert C. Gallo

-

Denise Koch & Stan Stovall

-

Josh Charles & Derek Waters

-

José Antonio Bowen & Shanaysha Sauls

-

Laurie DeYoung & Konan

-

D. Watkins & Clarence M. Mitchell IV

-

Gaia & Doreen Bolger

-

Deb Tillett & John Davis

-

Damian Mosley & Linwood Dame

-

A Conversation with Dan Deacon

-

The Burning Question

-