Meet the makers who are keeping Baltimore’s industrious spirit alive and well.

Arts & Culture

Made in Maryland

Meet the makers who are keeping Baltimore’s industrious spirit alive and well.

Ships, railroads, textiles, steel—Baltimore has long been a city of industry, priding itself on a bustling port, blue-collar work ethic, and small-town charm. Even today, as the city evolves and its harbor no longer brims with booming factories, that old industrious spirit lives on, thanks to both the big guys, like Under Armour and McCormick, and small-business craftspeople, like the folks who fill these pages. From leather workers and luthiers to bookbinders and bicycle manufacturers, these local makers are carrying the manufacturing torch, using their hands to create high-quality wares— and works of art.

JUBILEE BANJOS

A punk rock guitarist makes music history.

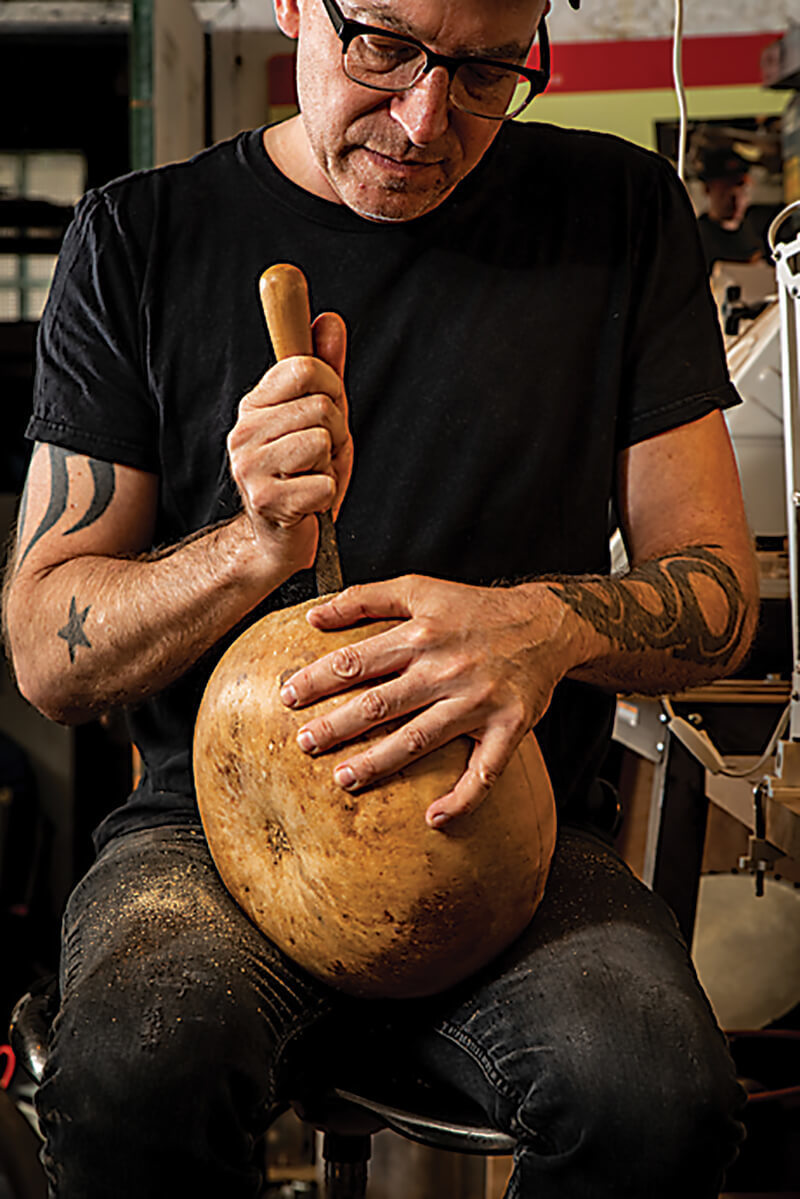

urrounded by sawdust, wood scraps, and a wall full of hollowed-out gourds in his basement workshop, Pete Ross is in the midst of making a custom instrument you’d never expect to find anywhere near the hands of this tattooed punk rock musician: a banjo. But during his younger years, Ross was working at an indie music store outside of Washington, D.C., when one record came over the stereo—an obscure African-American country string band from the 1940s. “Right place, right time,” he says. “I’d never heard anything like it.” It sent him down a rabbit hole of discovering not just the source of that haunting sound, but also the largely undocumented history of the instrument from which it came. In the years that followed, Ross would become an expert on the history of the instrument, from the early gourd banjos of African descent to the first commercial banjos born in Baltimore to the modern, metal-decked iterations. In turn, he learned about its connection to slavery, racism, and the evolution of American music, with the banjo first appropriated by blackface minstrel shows and later used by white country bluegrass musicians.

urrounded by sawdust, wood scraps, and a wall full of hollowed-out gourds in his basement workshop, Pete Ross is in the midst of making a custom instrument you’d never expect to find anywhere near the hands of this tattooed punk rock musician: a banjo. But during his younger years, Ross was working at an indie music store outside of Washington, D.C., when one record came over the stereo—an obscure African-American country string band from the 1940s. “Right place, right time,” he says. “I’d never heard anything like it.” It sent him down a rabbit hole of discovering not just the source of that haunting sound, but also the largely undocumented history of the instrument from which it came. In the years that followed, Ross would become an expert on the history of the instrument, from the early gourd banjos of African descent to the first commercial banjos born in Baltimore to the modern, metal-decked iterations. In turn, he learned about its connection to slavery, racism, and the evolution of American music, with the banjo first appropriated by blackface minstrel shows and later used by white country bluegrass musicians.

“I make my living doing this, but the mission has always been to undo a cultural injustice.”

—PETE ROSS

The former art major would also become one of the world’s great banjo luthiers, making replicas and his own renditions to be used in museum collections and by noted musicians, such as the late, great Mike Seeger of Baltimore bluegrass fame and Grammy-winning MacArthur Fellow Rhiannon Giddens. “This instrument was so essential to the formation of our American pop culture, I was disappointed to find there weren’t any still around,” says Ross. “So I started making them.” Downstairs, he works alone, hand-carving gourds and hardwood into working art forms with fine flourishes such as shell inlays and intricate hand-tied knots, considering historical context in every chord and peg. Upstairs, his partner, Kristina Gaddy, has also taken an interest in banjos and is even planning a potential book on the subject. These days, putting the electric guitar on the back burner, Ross has found that the true importance of this work is not as much about the music as it is about documenting and honoring lost history. “I make my living doing this,” he says, “but the mission has always been to undo a cultural injustice.”—LW

THE BAND’S ALL HERE

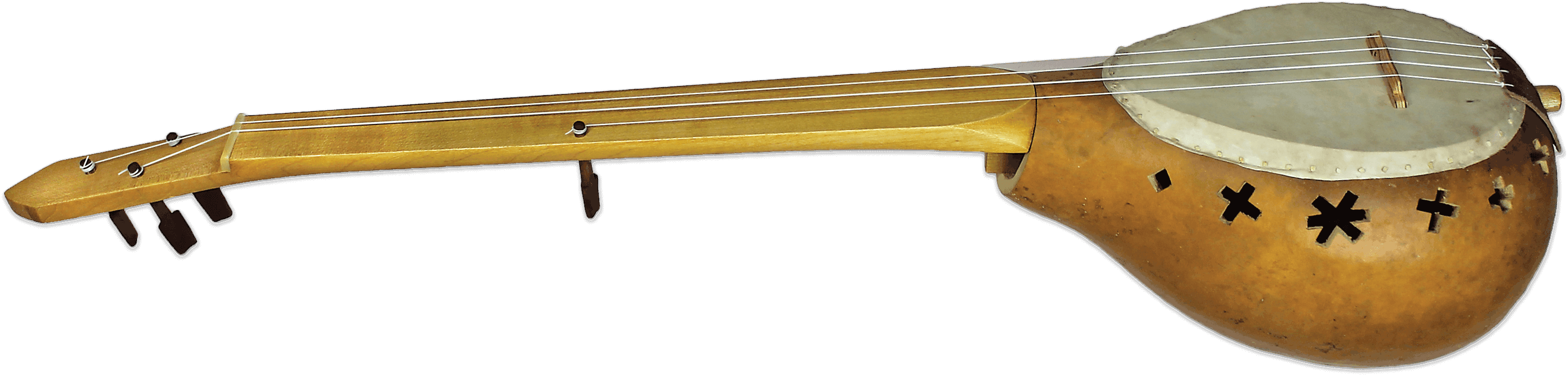

ROSS’ CUSTOM BANJOS SHOW THE INSTRUMENT’S EVOLUTION OVER TIME.

ROSS begins to carve

A DRIED GOURD FOR A FUTURE BANJO.

Gourd Banjos: Made of dried and stained gourd bodies and goatskin heads, these rustic instruments are reminiscent of the earliest banjos made in North America by enslaved Africans and African-Americans, built in both classic and contemporary styles.

Wooden-Rimmed Banjos: Inspired by iterations from the turn of the 20th century, these more modern versions of the instrument feature a classic wood-rimmed body, hardwood necks, steel strings, and intricate mother-of-pearl inlay details. They are used often by present-day musicians.

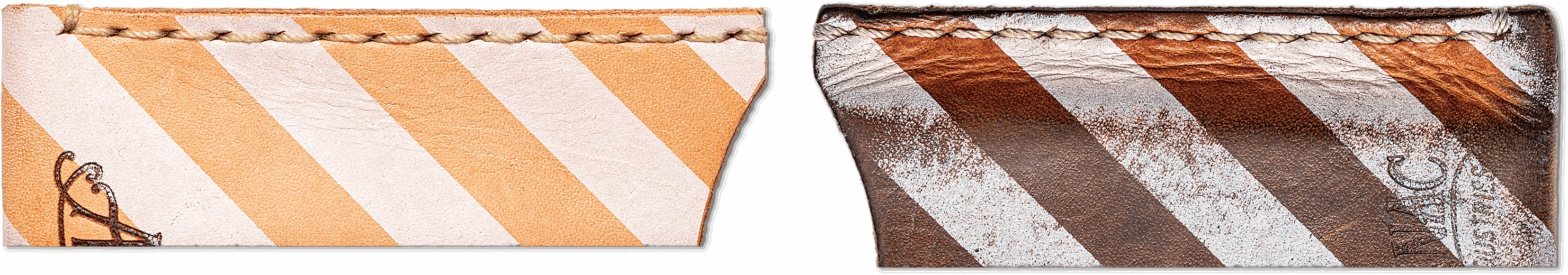

ALMANAC INDUSTRIES

A super mom crafts leather goods with love.

hitney Cecil is an impressive multitasker. Not only is she constantly juggling the many moving parts that go into Almanac Industries, her largely one-woman handcrafted goods business, but she’s also a full-time mom. “Who knows how we do it?” says Cecil from her Winston-Govans workshop space, which she often shares with her husband, Jacob, and their toddler and 5-year-old. “We taught ourselves almost everything.” In 2009, the MICA grad started Almanac as a small bindery that eventually evolved into a line of leather products after her tiny books continued to be confused for wallets. “From the start, we wanted to create something handmade in the old-fashioned way that would last a long time,” says Cecil, who draws inspiration from menswear.

hitney Cecil is an impressive multitasker. Not only is she constantly juggling the many moving parts that go into Almanac Industries, her largely one-woman handcrafted goods business, but she’s also a full-time mom. “Who knows how we do it?” says Cecil from her Winston-Govans workshop space, which she often shares with her husband, Jacob, and their toddler and 5-year-old. “We taught ourselves almost everything.” In 2009, the MICA grad started Almanac as a small bindery that eventually evolved into a line of leather products after her tiny books continued to be confused for wallets. “From the start, we wanted to create something handmade in the old-fashioned way that would last a long time,” says Cecil, who draws inspiration from menswear.

“we wanted to create something handmade in the old-fashioned way that was going to last a long time.”

—WHITNEY CECIL

Today, ethically sourced scraps of cowhide are piled beside her worn workbench, where she screenprints, paints, cuts, glues, hammers, brands, and stitches every card case, clutch, catch-all tray, and keychain, while toys are scattered across the cement floor. Last year, she also launched a kids’ line, Curated Circus. “From the start, my goal has been ‘keep it simple,’” says Cecil, who is now scheming desk accessories for Almanac, “but you just get all these ideas!”—LW

MAKERS HALL OF FAME

THE MASTERS OF MADE-IN-MARYLAND.

Artisan Glass Works

Old-style window glass for historic homes.

Berger Cookies

The iconic cookie of Baltimore. Nuff said.

BETTY COOKE DESIGNER JEWELRY

Wearable art by a veteran jeweler.

BLACK & DECKER

Back to Baltimore roots with Craftsman HQ in Middle River.

CHRISTOPHER SCHAEFER CLOTHIER

Custom suits with sartorial flair.

COTTON MONSTER

Wacky toys loved by kids and adults.

COW TALES

Old-school, cream-filled caramels of our youth.

DOMINO SUGAR

Our biggest, brightest sweetheart.

G. KRUG & SON

The nation’s oldest continually operating blacksmith shop.

GUTIERREZ STUDIOS

Masterful metalwork for the modern world.

J.O. SPICE

The seafood seasoning that’s actually on your steamed crabs.

MARK SUPIK & CO.

Beloved beer tap handles at local breweries.

MCSHANE BELL FOUNDRY

One of the oldest makers of magnificent church bells.

OLD BAY

On everything, always, from French fries to ice cream.

OTTERBEIN’S

The iconic cookie of Baltimore. Yeah, we said it twice.

OYIN HANDMADE

Gifts for natural hair, body, mind, and soul.

PAUL REED SMITH GUITARS

There’s Fender, Gibson, and this Eastern Shore luthier.

ROSEBUD PERFUME CO.

Tiny, all-purpose tins for every purse and pocket.

STX

The granddaddy of lacrosse sticks.

TOCHTERMAN’S FISHING TACKLE

Hand-tied flies for your inner fly-fisherman.

UNDER ARMOUR

From Kevin Plank’s grandmother’s basement to a global sportswear brand.

UNION CRAFT

Duckpin, forever. The king of local craft brews.

WOCKENFUSS CANDIES

The Willy Wonka of Baltimore.

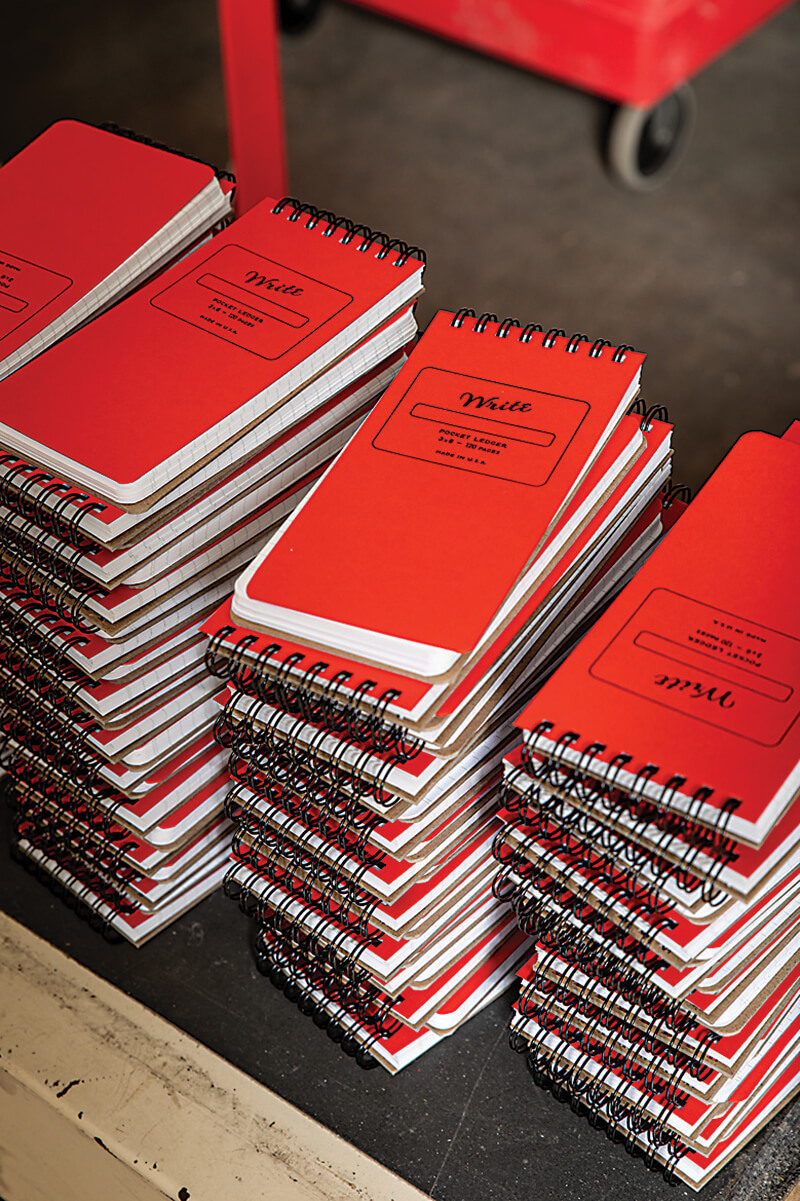

WRITE NOTEPADS

Long live pen and paper in Pigtown.

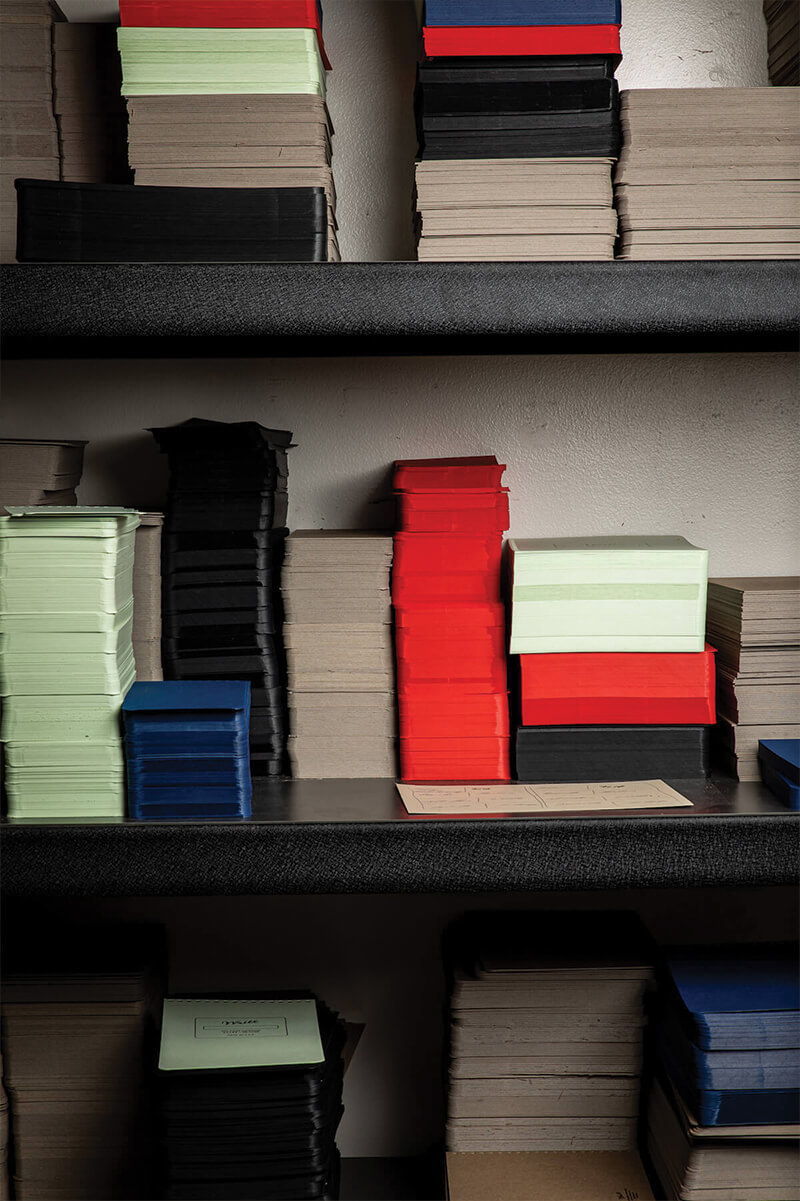

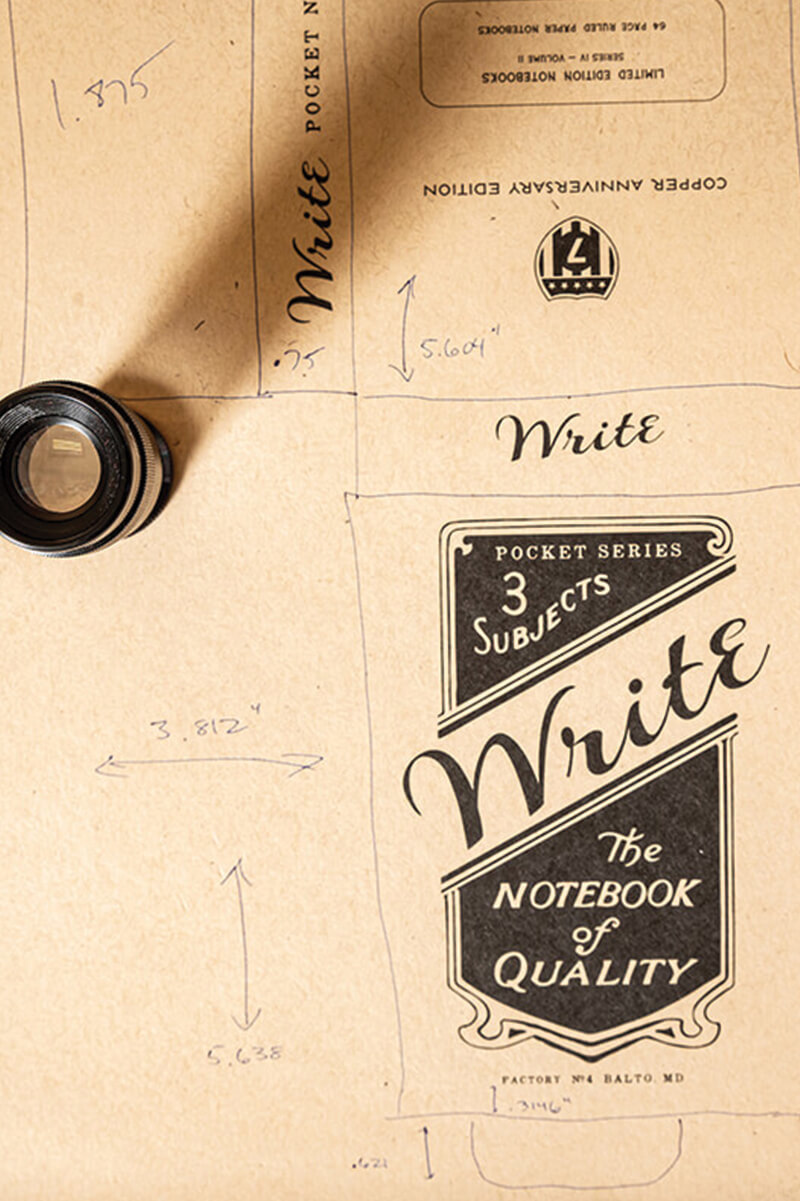

hris Rothe grew up around the smell of paper. He spent his teenage summers operating letterpresses at Allied Binding Co., his family’s bookbinding plant, where he fell in love with blank notebooks and the countless possibilities they could hold. So in 2011, Rothe decided to use the company’s resources and his own know-how to reimagine the spiral notebook. “We’re not reinventing the wheel,” he says, gesturing toward the piles of hard covers and color samples strewn throughout his team’s workshop. “We’re just building a better one.”

hris Rothe grew up around the smell of paper. He spent his teenage summers operating letterpresses at Allied Binding Co., his family’s bookbinding plant, where he fell in love with blank notebooks and the countless possibilities they could hold. So in 2011, Rothe decided to use the company’s resources and his own know-how to reimagine the spiral notebook. “We’re not reinventing the wheel,” he says, gesturing toward the piles of hard covers and color samples strewn throughout his team’s workshop. “We’re just building a better one.”

“We’re not reinventing the wheel – We’re just building a better one.”

—Chris Rothe

Now, Write Notepads Co.—situated in the back of Allied’s 50,000-square-foot facility in Pigtown—creates custom-printed notebooks and writing pads for thousands of clients, including the likes of Microsoft and Shopify, priding themselves on using high-quality recycled materials (their paper distributor is practically a family secret). With the help of old-school equipment, the fingerprints of the five-person crew are found on every step of the process, from cutting the paper to size to pressing the logo onto the covers to finally binding the stationary. There are plans to expand Write’s headquarters to a separate local facility with a retail space next year, but even as they continue to grow, Rothe says his small team’s top priority will always be to finely craft functional products for human hands. “We’ve found that our own neurotic ways of meticulously designing each piece resonates with those who are equally detail-oriented,” he says. “Notebooks are still very much a part of the lives of people who live in the tangible, written-word world.”—KP

MT. ROYAL SOAP CO.

This Remington suds shop gives new meaning to getting clean.

his is sort of a coming out for us,” announces Matthew Williams of Mount Royal Soap Co. “We’re all in recovery from alcohol and substance abuse.” Williams is sitting with his business partners, Samantha Kiffer and Pat Illes, in their sun-drenched, brick-and-mortar store in Remington, surrounded by soaps, scrubs, beard oils, balms, and lotions, all handcrafted here in small batches. The trio met each other while getting sober, and making these products became a positive place to direct their energy. “It was almost addictive, as something to fill our time with,” says Kiffer, who was initially concerned about the ingredients found in her skin care products, which always seemed to include environmentally unfriendly palm oil, with the only alternatives out of her price range. One day in her Mt. Royal Avenue apartment, she decided to start making her own, using self-imposed ingredient restraints (no parabens, sulfates, or animal products) that anyone could afford, and the hobby soon led to craft fairs, farmers’ markets, wholesale orders, and, eventually, their shop.

his is sort of a coming out for us,” announces Matthew Williams of Mount Royal Soap Co. “We’re all in recovery from alcohol and substance abuse.” Williams is sitting with his business partners, Samantha Kiffer and Pat Illes, in their sun-drenched, brick-and-mortar store in Remington, surrounded by soaps, scrubs, beard oils, balms, and lotions, all handcrafted here in small batches. The trio met each other while getting sober, and making these products became a positive place to direct their energy. “It was almost addictive, as something to fill our time with,” says Kiffer, who was initially concerned about the ingredients found in her skin care products, which always seemed to include environmentally unfriendly palm oil, with the only alternatives out of her price range. One day in her Mt. Royal Avenue apartment, she decided to start making her own, using self-imposed ingredient restraints (no parabens, sulfates, or animal products) that anyone could afford, and the hobby soon led to craft fairs, farmers’ markets, wholesale orders, and, eventually, their shop.

“There is something so fulfilling about creating a tangible good.”

—SAMANTHA KIFFER

this sweet basil, spearmint, and cedarwood soap is

inspired by springtime and the orioles.

inspired by springtime and the orioles.

Today, Kiffer comes up with a lot of the products and scents, but all three play a hand. Illes also acts as the unofficial chemist and handyman, even making the shop’s slicer out of guitar strings, while Williams, about to join the team full-time, also handles sales and orders. They move around their back production room with ease—it’s part kitchen, part laboratory, part design studio, with their fancy Hobart mixer the pièce de résistance. They mix, set, pour, and slice every soap, with each ingredient accounted for and added with purpose. “There is something so fulfilling about creating a tangible good,” says Kiffer. That means maintaining cult favorites—such as the Aw, Sugar scrub—but also constantly dreaming up new products. “I had an idea this very morning,” she says. While she was in the shower, of course.—JED

SUPER SUDS

The local shop’s most popular products.

Born to Rinse Shampoo: Container-free shampoo bars that actually lather.

Aw, Sugar Moisturizing Body Scrub: Luxe sugar scrubs (try the Lavender & Black Pepper) that magically become lotion in the shower.

The Clean Bohemian Soap: Made with olive oil, coconut oil, avocado oil . . . and National Bohemian beer.

Rosy Posy Body Lotion: Smells good, feels good, and does good, with anti-inflammatory rose water.

Liquid Soap: Seriously great for anything from cleaning dishes to cleaning your body, especially in Lemongrass & Peppermint.

BISHOP BIKES

A spin doctor makes masterpieces on wheels.

or Chris Bishop, the journey from being a kid growing up in Mt. Washington to becoming one of the world’s most coveted custom bicycle builders began with a BMX bike in the 1980s. “There were races all the time in Luckman Park,” says Bishop. “It wasn’t that safe, but it sure was fun.” The affinity for riding followed him to Portland, Oregon, where he dove into the region’s mountain bike scene and also took up carpentry. Making his way back home years later, Bishop would find a similar culture in Baltimore’s bike messenger community, and before long, he opened a small bike shop with friends near the Shot Tower. Even then, he found himself missing the design side of his woodworking days and started to study frame building. “I wanted to work with my hands again—get into the details and the craft of something,” he says. Bishop built his first bicycle in 2006 out of high-quality steel and his own welding, and he rapidly garnered praise for his craftsmanship and bespoke style. More than a decade later, his Bishop Bikes are renowned for their clean design, stunning paint, and, of course, smooth ride, by clients from across the globe. Hailed as one of the finest makers of such bikes today, he still builds them, one at a time, in his garage in Mt. Washington, back where it all began.—JF

or Chris Bishop, the journey from being a kid growing up in Mt. Washington to becoming one of the world’s most coveted custom bicycle builders began with a BMX bike in the 1980s. “There were races all the time in Luckman Park,” says Bishop. “It wasn’t that safe, but it sure was fun.” The affinity for riding followed him to Portland, Oregon, where he dove into the region’s mountain bike scene and also took up carpentry. Making his way back home years later, Bishop would find a similar culture in Baltimore’s bike messenger community, and before long, he opened a small bike shop with friends near the Shot Tower. Even then, he found himself missing the design side of his woodworking days and started to study frame building. “I wanted to work with my hands again—get into the details and the craft of something,” he says. Bishop built his first bicycle in 2006 out of high-quality steel and his own welding, and he rapidly garnered praise for his craftsmanship and bespoke style. More than a decade later, his Bishop Bikes are renowned for their clean design, stunning paint, and, of course, smooth ride, by clients from across the globe. Hailed as one of the finest makers of such bikes today, he still builds them, one at a time, in his garage in Mt. Washington, back where it all began.—JF

“I wanted to work with my hands again—get into the details and the craft of something.”

—Chris Bishop

TOP TOOLS

BISHOP’S GO-TO GADGETS.

TORCH HEAD: This precision heating instrument uses the process of silver brazing to create custom lug joints, turning steel tubes into two-wheeled workhorses.

FILES: These hand tools are for perfecting the details. “It’s the finishing that transforms the initial work into something fine and crisp,” says Bishop.

VISES: Among the simplest of devices, these tools are some of the most important, dictating how everything fits together. “This is really where the bike begins to take shape,” Bishop says.

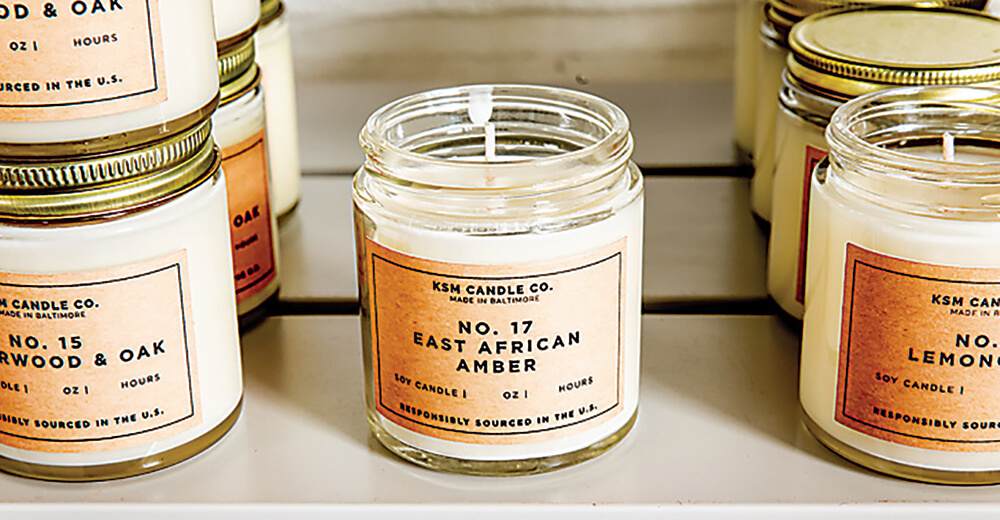

KSM Candle Co.

This small-batch candlemaker looks to the bright side.

fter years of sharing spaces, Letta Moore finally has a place to call her own. Bright white walls, work tables, and hundreds of glass jars fill the small spot that houses her KSM Candle Co. in Meadow Mill, where customers can peruse her ever-growing line of goods, smell custom scents, and even make candles themselves. KSM is the product of Moore’s creativity, and maybe also the tiniest bit of paranoia about what the future might hold. She spent 15 years as a marketing executive before The Walking Dead inspired her to lean into her other talents. “I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, if there’s ever a zombie apocalypse, this marketing experience isn’t going to translate into anything useful,’” she says with a laugh. “So I started mastering all the things I knew how to do with my hands.” At the time, those doomsday skills included knitting, candle making, and fashioning metal jewelry (hence the original name—Knits, Soy and Metal), and in 2014, the first version of her company was born as an e-commerce site.

fter years of sharing spaces, Letta Moore finally has a place to call her own. Bright white walls, work tables, and hundreds of glass jars fill the small spot that houses her KSM Candle Co. in Meadow Mill, where customers can peruse her ever-growing line of goods, smell custom scents, and even make candles themselves. KSM is the product of Moore’s creativity, and maybe also the tiniest bit of paranoia about what the future might hold. She spent 15 years as a marketing executive before The Walking Dead inspired her to lean into her other talents. “I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, if there’s ever a zombie apocalypse, this marketing experience isn’t going to translate into anything useful,’” she says with a laugh. “So I started mastering all the things I knew how to do with my hands.” At the time, those doomsday skills included knitting, candle making, and fashioning metal jewelry (hence the original name—Knits, Soy and Metal), and in 2014, the first version of her company was born as an e-commerce site.

“So I started mastering all the things I knew how to do with my hands.”

—Letta Moore

Over the years, Moore’s focus has shifted primarily to her soy candles and other good-smelling home products (more than 50 handcrafted scents and counting), prompting the name change to simply KSM Candle Co. earlier this year. Longtime devotees can still find Moore’s products at Keepers Vintage in Mt. Vernon, but her sunny new brick-and-mortar in Woodberry showcases clean shelves full of hand-poured candles in inspired fragrances such as black currant tea, patchouli and bergamot, and “Juneteenth,” a hibiscus scent inspired by the summer celebration of emancipation. After relying on other people’s open doors for classes and pop-ups, Moore now shares her workshop space with those who need a place to host their own, free of charge. “I want to give new people the opportunity,” Moore says. “I just want to contribute back to Baltimore.” —CJ

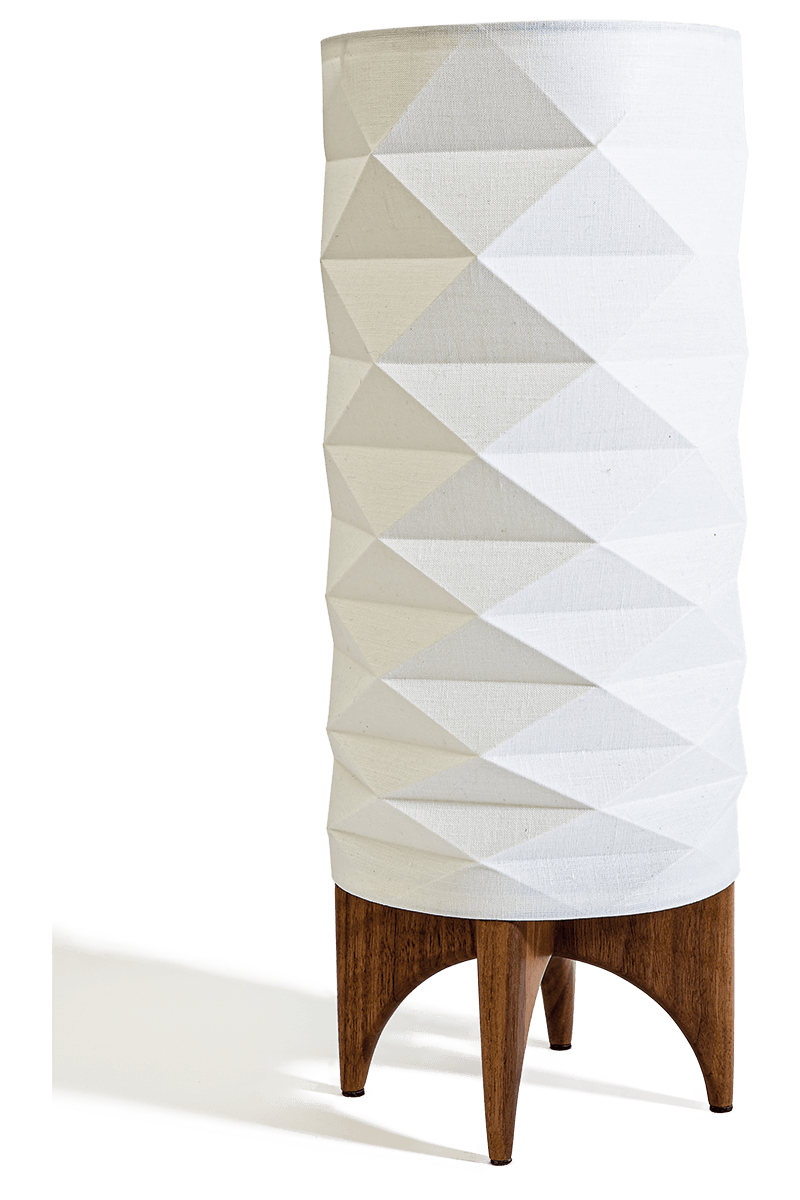

LA LOUPE DESIGN

For these Seton Hill artists, everything is illuminated.

hen textile designer Jorgelina Lopez was invited to teach an origami workshop at The Baltimore Museum of Art, she happily rose to the challenge. There was only one issue: First, Lopez had to teach herself the ancient art of paper folding. “I did a lot of research, for three months, before the workshop started,” she says, sitting in her Seton Hill studio and home, which she shares with her Peruvian craftsman husband, Marco Duenas, and their three cats. Once she mastered the basics, Lopez pushed her experimentation a step further, and, well, saw the light. “I wanted to translate the origami technique to textiles,” she says, and soon after, she discovered that she could use the same technique to design the lamps of her home décor line, swapping out Irish linen for paper. The Argentine-born artist and founder of La Loupe Design has always been drawn to lights, as well as Japanese design. “Lights are sculptural but functional at the same time,” she says. “And there’s something about Japanese simplicity that I feel a connection to.” Meanwhile, Duenas builds the spare wooden bases on which the shades sit, invoking mid-century minimalism and making the duo very much in sync. Sums up Lopez, “We collaborate with each of us expressing ourselves in different ways.”—JM

hen textile designer Jorgelina Lopez was invited to teach an origami workshop at The Baltimore Museum of Art, she happily rose to the challenge. There was only one issue: First, Lopez had to teach herself the ancient art of paper folding. “I did a lot of research, for three months, before the workshop started,” she says, sitting in her Seton Hill studio and home, which she shares with her Peruvian craftsman husband, Marco Duenas, and their three cats. Once she mastered the basics, Lopez pushed her experimentation a step further, and, well, saw the light. “I wanted to translate the origami technique to textiles,” she says, and soon after, she discovered that she could use the same technique to design the lamps of her home décor line, swapping out Irish linen for paper. The Argentine-born artist and founder of La Loupe Design has always been drawn to lights, as well as Japanese design. “Lights are sculptural but functional at the same time,” she says. “And there’s something about Japanese simplicity that I feel a connection to.” Meanwhile, Duenas builds the spare wooden bases on which the shades sit, invoking mid-century minimalism and making the duo very much in sync. Sums up Lopez, “We collaborate with each of us expressing ourselves in different ways.”—JM

“DON’T TRY TO BE PERFECT. WHEN YOU FOLD PAPER, ALL YOU NEED IS PATIENCE.”

—JORGELINA LOPEZ

ORIGAMI 101

What you’ll need to get started, according to Lopez.

Lopez begins to fold a Paper lampshade.

A How-To Book: She highly recommends Folding Techniques for Designers: From Sheet to Form by Paul Jackson.

Paper: “Any kind of medium-weight paper will work.”

Simple Shapes: “Start simple. Once you understand how the paper behaves, you can move on to more complicated shapes.”

A Surface: She works on a table in her art studio, but any clean, flat surface, even the floor, will do.

Attitude is Everything: “Don’t try to be perfect. When you fold paper, all you need is patience.”

SANDTOWN FURNITURE CO.

For Trees, a second chance grows in South Baltimore.

t’s quiet walking down the residential Belt Street in Riverside, but once you reach the end, nearing the old brick workshop of Sandtown Furniture Co., the air soon fills with the sounds of rock ’n’ roll and the whining buzz of saws and planers. Sawdust hangs in the air, wood chips blanket the floor, and stacks of salvaged lumber, packed into every corner and crevice, resemble a giant Jenga game. “It may not look like it,” says James Battaglia, head of production, “but there’s a method to the madness.” In fact, this all started with a moment of clarity. Back in 2010, Battaglia’s partner, Will Phillips, was volunteering with Habitat For Humanity, refurbishing old rowhomes in Sandtown-Winchester (the origin of company’s name), when he noticed that many of the beams and boards, often dating back to the late 1800s, were headed toward the landfill. “The wood really stood out to me—this beautiful, hundred-year-old material,” says Phillips. “It seemed like a shame to throw it away.” Teaming up with John Bolster of New Renaissance, a local design and construction company, he started saving that discarded wood with the purpose of turning it into new furniture, launching Sandtown later that year.

t’s quiet walking down the residential Belt Street in Riverside, but once you reach the end, nearing the old brick workshop of Sandtown Furniture Co., the air soon fills with the sounds of rock ’n’ roll and the whining buzz of saws and planers. Sawdust hangs in the air, wood chips blanket the floor, and stacks of salvaged lumber, packed into every corner and crevice, resemble a giant Jenga game. “It may not look like it,” says James Battaglia, head of production, “but there’s a method to the madness.” In fact, this all started with a moment of clarity. Back in 2010, Battaglia’s partner, Will Phillips, was volunteering with Habitat For Humanity, refurbishing old rowhomes in Sandtown-Winchester (the origin of company’s name), when he noticed that many of the beams and boards, often dating back to the late 1800s, were headed toward the landfill. “The wood really stood out to me—this beautiful, hundred-year-old material,” says Phillips. “It seemed like a shame to throw it away.” Teaming up with John Bolster of New Renaissance, a local design and construction company, he started saving that discarded wood with the purpose of turning it into new furniture, launching Sandtown later that year.

“We try as much as we can to highlight all those marks of character from its previous life.”

—Will Phillips

Today, another half-dozen men work away at milling, planing, sanding, staining, and assembling the boards into sleek, stylish tables, desks, and consoles. Rusted nails are removed, and knots are filled in, but the flaws remain, celebrating the wood’s history. “We try as much as we can to highlight all those marks of character from its previous life,” Phillips says. With a growing client base that includes the recently renovated Broadway and Cross Street Markets, they’re now looking ahead to a major expansion with a high-end showroom and production facility in 2020. But even with fancy new digs, they still plan on sticking to their scrappy roots to continue saving some of Baltimore’s history. “These guys take a lot of pride in what they do,” says Phillips. “Every piece of wood passes through the hands of someone who really cares about their craft, and that’s a big part of the final product.”—LW

WITH THE GRAIN

AT SANDTOWN, EVERY wood has its own STYLE AND strengths.

in addition to furniture, THE SHOP also CREATES CUSTOM pieces, like this frame.

PINE: In particular, old-growth heartwood pine, aka the center of an ancient tree, is prized for its warm tones, intricate grain, and historical rarity.

OAK: American oak, both red and white, makes a good go-to wood for everyday products with its light color, classic grain, and durability.

WALNUT: Black walnut packs a deep, rich color and strong, straight lines for a powerful statement for any piece of furniture.