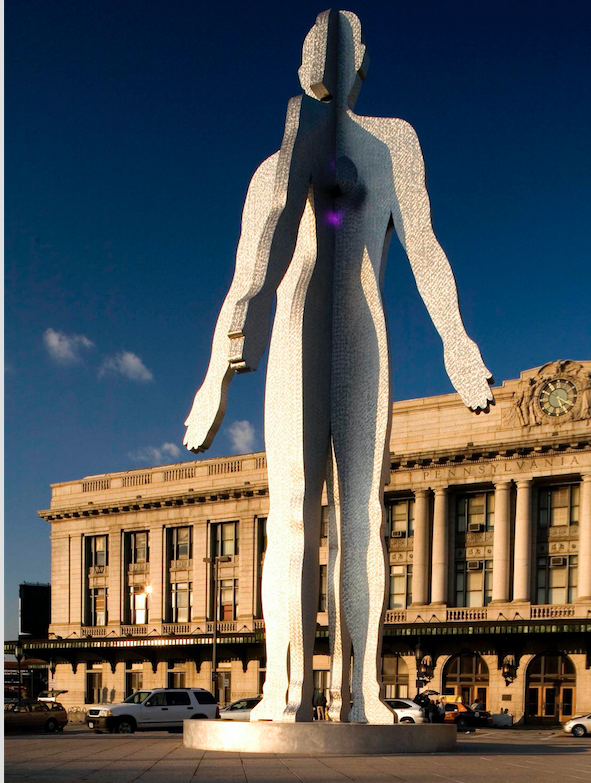

It was a 52-foot, 10-ton object of controversy, curiosity, and for the most part, derision, when it was installed in front of Penn Station in 2004. A Baltimore Sun editorial described the aluminum, five-story Male/Female work at the time of its placement in the city-owned plaza south of the station as “oversized, underdressed and woefully out of place.”

Sun columnist Dan Rodricks wrote that artist Jonathan Borofsky’s intersecting male and female silhouettes resembled the robot Gort from the sci-fi, horror movie The Day the Earth Stood Still. A local cabbie, who regularly picked up fares at the station, called it “an abomination” in one story. Several times, City Paper readers voted the massive sculpture—a $750,000 donation from the Municipal Arts Society— Baltimore’s “Best Eyesore.”

Almost immediately, it prompted chatter about moving it from its prominent position outside the 1911-built Beaux-Arts style station.

And now, oddly enough, just as the city seems to have finally grown accustomed to it, the fate of long-controversial Male/Female may be in doubt.

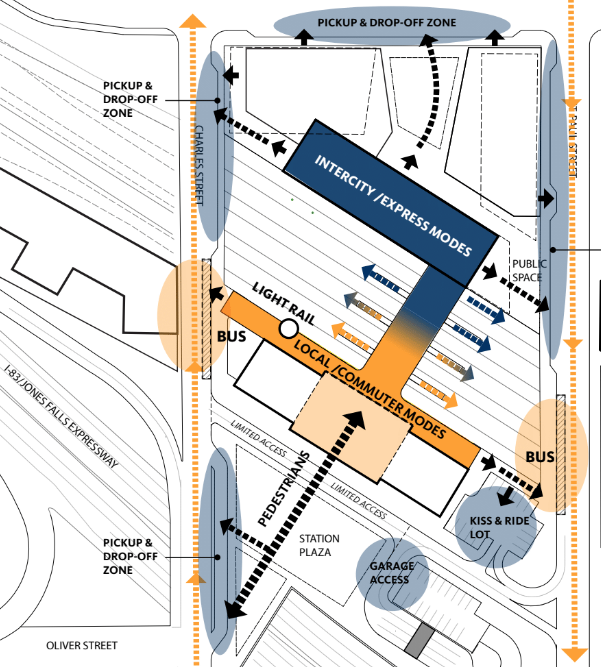

In order to handle the new generation of high-speed Acela trains, as well as the expectation of more passengers in coming years, Amtrak has pledged a $90 million overhaul of Penn Station. Those plans include a transformation of the historic station into a more pedestrian, bicycle, bus, and cab-friendly transit hub—and, if developers can raise more funds—a new mixed-use development in the surrounding area.

No official has said the giant sculpture needs to be moved to remake Penn Station. No one has indicated it will stay. There is simply is no sight of the 52-foot statue in current renderings and maps. Bill Struever, CEO of Cross Street Partners, one of the developers and planners on the Amtrak project, noted in an email that indeed the sculpture had engendered strong feelings over the years. He also stated he “is staying agnostic on the statue.” Ultimately, Struever says, he expects a resolution on the development of the south station plaza—and thus the statue—will grow out of a community planning process.

The current working proposal calls for moving the taxi/drop-off area to Charles and St. Paul streets, which will serve a new Lanvale Street rail concourse on the north side of the station. That plan, Struever says, creates an opportunity to rebuild the south station plaza into a more pedestrian friendly space with the potential for events and programming.

In the meantime, however, the statue has grown on at least some Baltimoreans over the last few years. As Baltimore magazine contributor Ed Gunts noted in a short piece in 2015, one early defender of the Male/Female statue was Bill Griffith, creator of the Zippy the Pinhead comic strip, in which the sculpture has appeared. John Waters has said he likes it, too. Rebecca Hoffberger, founder and director of the American Visionary Art Museum, noted several years ago that even “The Eiffel Tower was detested” when it went up.

Asked again last week about the statue, Hoffberger said she wished “there was something that was more in tune with the station’s history as a link that gave homage.”

“It’s there and I think there are people that love it,” she says. “I don’t know how thematically it was decided on. There’s a bigger issue—the front of Penn Station is really historic and iconic to Baltimore,” adding the structure may be obscuring that. “I’m very big on preserving older architecture particularly of iconic sites.”

Baltimore architect and artist Jerome Gray said he believes the size of the statue overwhelmed city viewers at first, but since its installation people have become accustomed to it. He added the sculpture’s provocative intersection of the male and female forms—and its colorful, single, pulsating heart, widely visible at night—personally appeals. “I love weird things,” he says. “And I like anything that challenges you. In that way, it’s great. It makes you think.” (Initially, the sculpture’s beating heart was to be red, but it was switched to blue-magenta at the city’s request out of concerns the color red would be seen as a reminder of the city’s tragic homicide rate.)

Gray adds that it’s not unprecedented for the city to move works of art. The Orpheus statute, for example, at Fort McHenry was shifted from its original location. Others around Druid Hill Park have been moved in the past.

In 2015, City Paper contributor Michael Farley called the statue an “accidental monument to a consideration (or lack thereof) of gender identity and sex that’s distinctly Baltimorean.” He nominated it “the kinkiest artwork” in the city.

Borofsky, for what it’s worth, never liked to comment too much about the themes in his own work, preferring to leave it for the viewer’s interpretation. His public projects, including other large scale human forms, can be found around the world.

Eli Pousson, formerly of Baltimore Heritage, moved to the city a few years after the installation of the statue, but quickly became aware of the criticism of work. “It was abstract, difficult to categorize in terms of explicit meaning,” Pousson says. “It wasn’t your normal, marble famous guy. It plays with the [traditional] masculine and feminine forms, which also probably invited some of that response.” It’s interesting, Pousson continues, that today more people seem to respond positively to the statue as gender, sex, and queer identities and norms evolve in the eyes of society.

“Personally, I’m a fan,” Pousson says. “I’d suggest rather than spending money to take down public art, the city and developers use the money to put up more public art.”