Baltimore just got gifted with its own little (and in some ways massive) slice of the Venice Biennale.

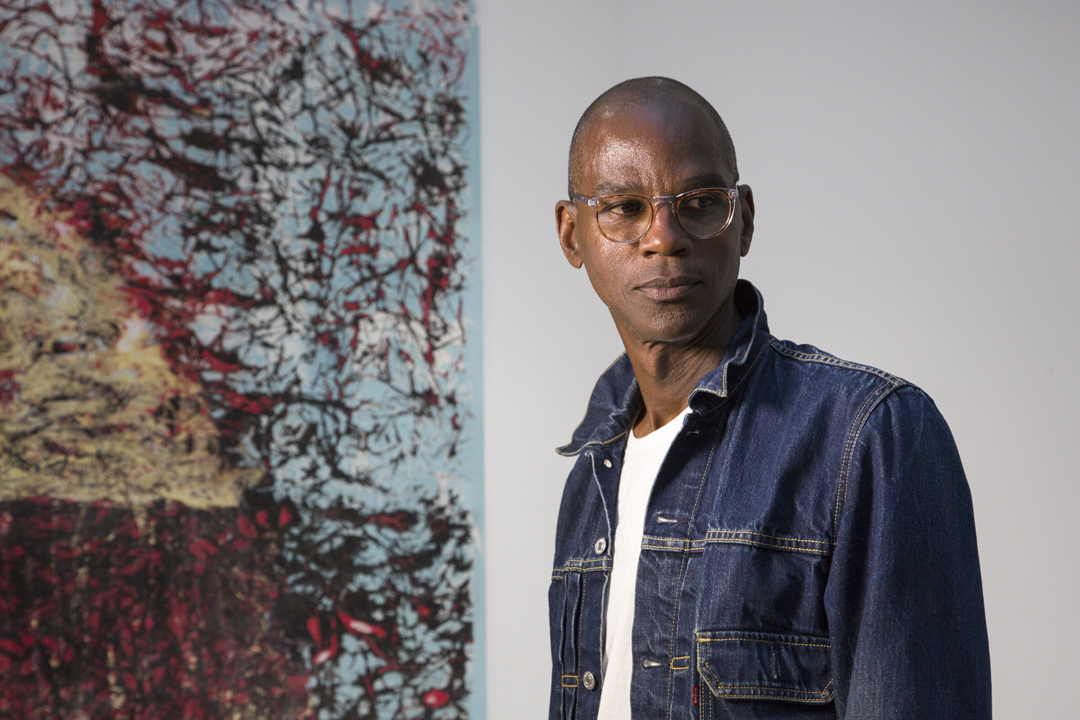

Artist Mark Bradford, who represented the U.S. in the 2017 Venice Biennale, has deconstructed and reinstalled several of his pieces that were exhibited there to create a new iteration of the exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Mark Bradford: Tomorrow Is Another Day will be on view from September 23 through March 3, 2019.

On Saturday afternoon, as part of a four-hour Community Celebration at the BMA, Bradford will be in conversation with BMA director Christopher Bedford and senior curator Katy Siegel, who co-curated the exhibition here and in Venice. Guests can preview the show before its official opening on Sunday.

In his work and in talking about it, Bradford doesn’t shy away from confronting the complexities he’s experienced while navigating the world as a black man, a gay man, and a tall man (at 6-foot-8, he says he’s constantly aware of his physical body and how it relates to its environment and other people). Through large abstract mixed-media pieces, sculpture, and video, he processes his experiences within the framework of society and its various communities and cultures—especially those that have been marginalized. He often works with found materials, like dyed hair endpapers, that speak to these communities.

Some highlights in the show include the huge, gnarly sculpture Medusa—made from paint, paper, rope, and caulk and reminiscent of Medusa’s snake-like locks but in this case a commentary of sorts on empowered, self-righteous women; the large and solemn pieces made from repetitive rows of the aforementioned endpapers from a hair salon, which achieve a calm, meditative quality and have a tactile, water-like depth; the emotive trilogy of “Cosmic Paintings,” as the BMA describes them, that includes the show’s striking title piece; and his Spoiled Foot installation, which starts off the show and is constructed of canvas, lumber, cut-up road maps, used roofing material, and what Bradford calls merchant posters—signage collected from in-crisis communities that advertise things like “We Pay Cash for Homes,” 24-hour child care, and bed bugs extermination.

That piece hits on Bradford’s overarching theme of expulsion and how to navigate it. People can’t physically get to the center of the gallery where Spoiled Foot is installed because the piece stretches wall to wall and covers the ceiling, obstructing the space—a tangible representation of people who are, or feel they are, cast out of a particular community. Viewers move through that space much in that same way but in a literal, physical sense—ducking and dodging, conscious of the narrow space in which they have to walk through to get to the next gallery.

As Bradford puts it, “The center is not always available to everyone. . . . I wanted people to feel how it feels.”

This of course raises questions: Who owns the “center”? Who can occupy it?

“I became really fascinated by place,” he says.

Following that line of thought, context changes when a show is installed on the other side of the world.

“Bringing it to a city that’s predominately African American—it definitely changes it,” Bradford said on Thursday. “I think it reinvigorates some of the ideas.”

Roughly 380,000 people attended the 2017 Venice Biennale (the largest crowd at the event to date), but Bradford, as well as Bedford and others on the BMA staff, says he thinks the show looks even better here, and he’s excited that it will be interpreted—or misinterpreted—differently here because of its new geographic location.

He’ll present a slideshow during his talk on Saturday, which is something he’s never done. He says he’s doing it specifically because he’s interested in engaging with the Baltimore audience.

While in Baltimore, he’s spent time with the Greenmount West Community Center, a community art space for children and their families. He’s also spearheaded its Greenmount West Power Press program, which allows kids to learn how to screen print. Tote bags and other items are available to purchase at a popup shop at the BMA to help support GWCC.

As Bedford put it, Bradford has one foot firmly planted in the studio and another in the community. He’s known for his passionate care in creating inclusive, safe spaces for youth.

In Venice, he began a partnership with the nonprofit Rio Terà dei Pensieri called called Process Collettivo, which provided inmates the opportunity to create artisanal products to sell and ultimately help with their reintegration upon being released.

In L.A., where he is based, he cofounded Art + Practice, a contemporary art gallery open to the public that doubles as an educational space for youth to develop skills and gain access to housing and employment opportunities.

In some cases, trying to bring people to a museum is backwards, he says. “I think we have to go there. How about us going there and feeling a little bit uncomfortable.”

When speaking about his time at GWCC, he says, “That’s where the hope comes in. You give the kids a safe space and allow them to be them. The world’s gonna be fine,” he adds, not sarcastically. “We just have to do more and more and more of this.”

He goes on to tell the story about his debilitating childhood fear of the dark. He’d look out his window at night at the moon and tell himself a story: that God poked a hole through the sky, and that’s the little window of light shining through, reminding us that the light is still there—that tomorrow is another day.