Arts & Culture

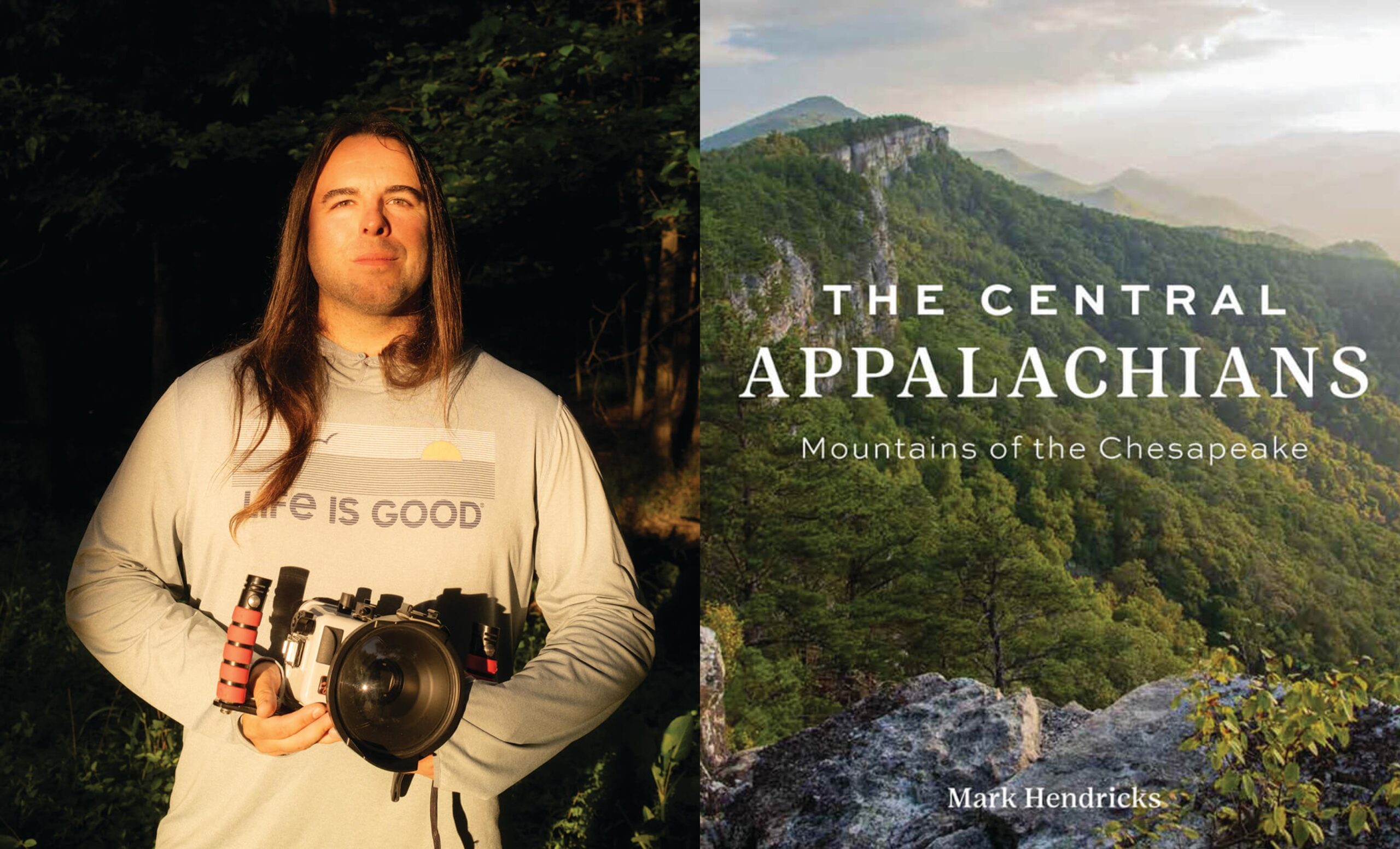

Mark Hendricks’ Latest Photo Book Celebrates the Mountainous Areas of the DMV

The Baltimore native photographer's images are not only beautiful, but they also deepen our understanding of the iconic eastern mountain range and its environmental importance.

Mark Hendricks is a former marine mammal biologist who turned to his camera as a storytelling and conservation tool. A Baltimore City native and adjunct professor at Towson University, where he co-directs the Animal Behavior Program, Hendricks has long focused his lens on Maryland’s coastal waterways and the Chesapeake Bay watershed. His first book, Natural Wonders of Assateague Island, a 2017 Foreword Reviews award-winner, went beyond the island’s pristine beaches and wild horses to document the area’s stunning biodiversity.

His latest book of photography, The Central Appalachians: Mountains of the Chesapeake, celebrates the flora and fauna of the mountainous areas of Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia, which provide most of the Chesapeake Bay’s fresh water. Among his seasonal portfolios are essays on ecologists, encounters with black bears and a bobcat—and a Baltimore-based through hiker. Hendricks’ work has appeared in National Geographic, Audubon, and Nature Photographer. Not only are his images beautiful, but they also deepen our understanding of the iconic eastern mountain range and its environmental importance.

First, I’ve got to ask about the photo of the pink American flamingoes on a south-central Pennsylvania pond not far from Baltimore. Pink flamingo lawn ornaments are common here, but not the real thing, right?

They are very, very rare. A bunch of flamingos were migrating through Cuba and the Caribbean, and they got blown off course by a hurricane and started showing up in Florida—no surprise there—and then further north in Georgia, the Outer Banks, and then Pennsylvania. The last sighting in Maryland was on Assateague Island in the ’70s.

The black bear cub looking at the camera while climbing a tree in the George Washington National Forest is also an incredible image.

Their population is rising in the Central Appalachians. Ansel Adams used to say chance favors the prepared mind, and I went there frequently, but that was a lucky moment. There’s also a picture of a bear I knew and her two cubs. It’s funny, too, if you watch bear cubs, it is just like watching puppies in the way they wrestle with each other.

What was the turning point, in terms of your career switch from marine mammal biologist to nature photographer and writer?

As a kid I had National Geographic on the bookshelves and coffee-table books on the Amazon and Serengeti. And I always had my personal “art” projects—usually done with cheap plastic roll film cameras that I’d get developed at Rite Aid. When I started doing it more seriously, it forced me to become a better outdoorsman, and then I also liked the idea of merging art and science. I thought if I got stories published—I write, too—that I could reach an audience that I couldn’t do any other way. Now I have this “passport” to explore things with photography that I wouldn’t have had if I’d just stayed with marine mammal biology.

Well, the photos and story of the bull elk herd in north-central Pennsylvania certainly feel like a passport to another time and place.

Yeah, but everything in the book is also only a one, two, or four-hour drive from Baltimore. The elk were reintroduced into Pennsylvania in 1913 after the last eastern elk was killed. At dawn and dusk they make this mournful bugle call during mating season. The males also challenge each other, and you’ll see these epic battles between evenly matched behemoths like if you were in Montana.

I also love the photos and story of retired National Aquarium senior director and through-hiker Bill Minarek—and your reconnection.

I was volunteer and part-time paid employee in high school, and later, a dolphin trainer at the aquarium. That’s where I met my wife, who was also a dolphin trainer. Bill was getting to Western Maryland and so we met up and I hiked the trail with him to Annapolis Rocks. Last time I saw him, he was this clean-cut, supervisor-looking dude, and then I see this form of a long-distance runner-type body with a scraggly beard and a big, old backpack—and it’s him. Hiking the entire trail was an idea he’d had since he was a Boy Scout and his scout leader pointed out a white blaze on the Appalachian Trail and told the troops, “If you go this way, you’ll end up in Maine. If you go this way and don’t stop, you’ll end up in Georgia.” That never left him. When I met him—Maryland is halfway—he was in the middle of it. He was living it. And he did it.