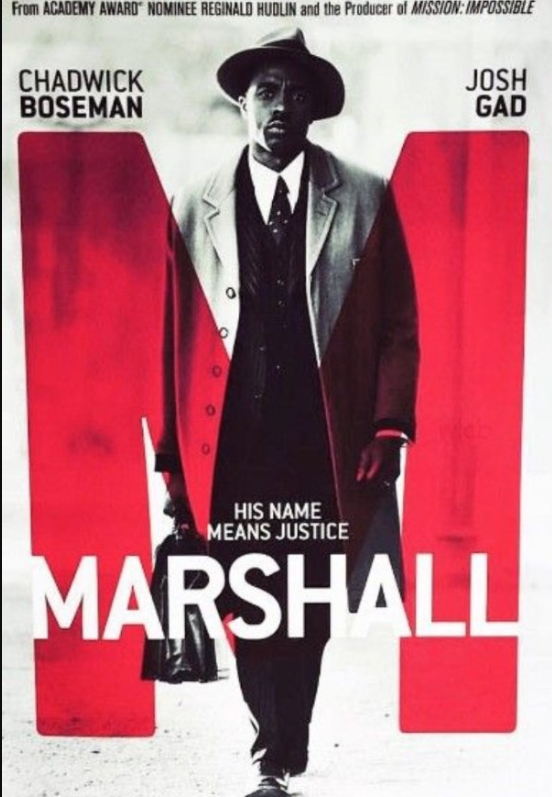

On the heels of the 50th anniversary of the swearing-in of Thurgood Marshall to the Supreme Court earlier this month, Marshall, a compelling courtroom drama built around the legendary Baltimore civil rights fighter opens in theaters this weekend.

Based on a real Connecticut case taken up by the NAACP and Marshall in 1940, the film plays like a legal potboiler—a black chauffer has been accused of rape by a rich white woman—while offering glimpses of the legendary attorney as a young man.

(For a deeper dive into Marshall’s Baltimore roots and seminal role in U.S. history, check our story from our August “Best of Baltimore” issue. For a full review of Marshall, read managing editor and pop culture critic Max Weiss’ piece.)

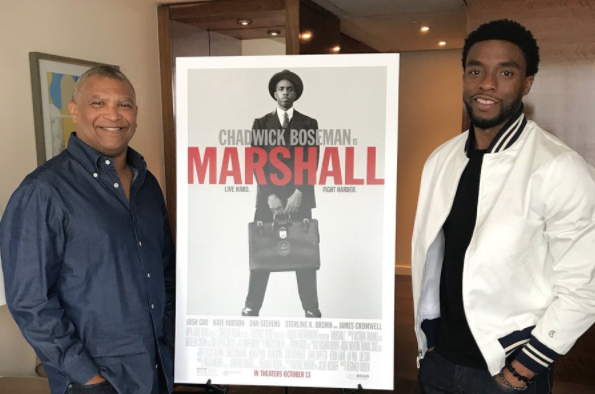

Before the release of the film, which has been receiving positive reviews, we sat down at the Four Seasons Hotel Baltimore with award-winning director Reginald Hudlin, whose previously produced works include Django Unchained, and Marshall star Chadwick Boseman, previously known for his portrayals of James Brown in Get on Up and Jackie Robinson in 42.

[To Hudlin]: It was particularly nice to see Marshall’s first big civil rights win—desegregating the University of Maryland law school, which would not admit him—get a mention in the film.

Hudlin: [The University of Maryland law school case] was such a pivotal story, it had to be in the film, to me. It shows his complete intolerance for racism and those kinds of barriers. That it would be the first thing he did after getting a law degree, and to succeed, speaks to his intelligence and his ability as an attorney.

It also speaks to his ability to hold a grudge. Marshall somewhat famously did not come back to Baltimore when the law library was named after him.

Hudlin: [Laughter] I didn’t know that. That’s great.

Why the Joseph Spell case instead of the Brown v. Board of Education decision?

Hudlin: When you are going to do the cradle to grave biopic, there is a kind weariness that people have. So I said, ‘Let’s not do that movie. Let’s make a legal thriller that would be exciting if the protagonist, the lead attorney, were Joe Smith.’ This is an exciting case. A case where we don’t know the outcome like Brown v. Board of Education … You don’t know this case. You don’t know the outcome, but so many of the themes of the case are still relevant now—like you don’t have to be a saint not to be guilty—that is the issue with every police shooting now, ‘Well, he’s no angel.’

So if they love this case, great, and please go learn more about Thurgood Marshall, one of the greatest men in American history.

[To Boseman]: How much research did you do in preparation for portraying Marshall?

Boseman: I had some video footage to look at. Not a lot. I usually have endless amounts—like baseball footage [of Jackie Robinson]. Not a lot of courtroom footage of Marshall arguing before the Supreme Court. What was important for me, was to get a sense of Thurgood Marshall from the books, from Young Thurgood [written by University of Maryland law professor Larry Gibson], from Thurgood Marshall: American Revolutionary [by Juan Williams] and what was said about him. And then reading about the other cases he argued, learning about his perseverance. The thing about being a civil rights attorney is that it’s not about winning all the time—it’s often about taking losing cases and taking them to the Supreme Court, which is what he did.

Like a lawyer, you did a lot of reading.

Boseman: To me, there is a great of information in the written word about him. I think he had a sizable ego, but he also had a sense of humor where he could bring together other people with sizable egos and get them to work together and that’s part of his genius. He wasn’t the person that always had to be the ‘A’ person in the room—although he always was the ‘A’ person in the room. He could tell a joke and compliment another person. He used a lot of different tools to get to his goals. Just a very well rounded individual, who could do a lot of things. He could spend the night drinking, debating, and arguing strategy with other NAACP officials and then get up the next morning and get the job done. That’s who he was. The research that’s written is interesting enough not to have video footage.

[To Boseman]: Is it easier to play someone you’ve met?

Boseman: I don’t know to be honest. You are always trying to find the essence of the person. You have a different body, a different history, and you are sort of pouring their history inside of your cup and becoming them. It’s the ability to take that essence and embody it and give it new life—that we are really judging [when an actor portrays a real-life figure]. It’s not an imitation. It’s not comedy. It’s the spirit of the person you are really embodying.

Marshall in this case, for all intents and purposes, is under a gag order in the courtroom and has to operate and argue through his white attorney and legal partner. Obviously, that was a challenge for Marshall at the time. Was it for you?

Boseman: You know a person from the obstacles they’ve overcome, so I felt like it was the best possible problem to have and best possible conflict. He becomes a coach, a mentor, but he’s still the lead of the movie, he’s still the protagonist of the film. I say that because a lot of time you have a story where the black person should be the lead and the white person somehow—because of how Hollywood works—comes in and takes over the movie. We were mindful of that as well.

There’s a lot of layering of the broader character of Marshall and the broader nature of the NAACP’s mission in the film, which people who are familiar with his history will pick up on. That had to be very intentional.

Hudlin: A lot of people had never seen an individual like Thurgood Marshall before [when he arrived to town to argue a case in court.] He insisted on you dealing with his full humanity. He did not allow himself to be reduced to anything less he was. That, and he was always the smartest guy in any room he walked into. He was making a legal case, but there was also a bit of therapy going on every time he dealt with these people [who held racist views] because he had to explode all these preconceptions.

A coincidence the film is coming around the time of the 50th anniversary of Marshall’s appointment to the Supreme Court?

Hudlin: It is one of those happy coincidences of things coming together when you make a film.

Boseman: I hope it brings more recognition [to Marshall]. You can’t walk outside without there being some impact he had on your life.

Hudlin: You think about your life [in this country]. You think about the framers of the Constitution, the guys who wrote it. Then there’s the guy who actually made America live up to its promise as a nation—that’s Thurgood Marshall. If you are going to add a face onto Mount Rushmore, he’s a pretty good choice.

Is there something happening culturally—with Hidden Figures, Selma, Moonlight, Fences, 42, etc.—that more black films are finally reaching broad American audiences? Hidden Figures, for example, was a huge box office success.

Hudlin: I think the audience has been ready. I think the folks between the filmmakers and the audience needed to get out of the way and allow us to make the films people want to see. It’s very satisfying for me when Marshall plays equally well to men, women, every racial group—it doesn’t matter. Everyone who sees the movie responds the same way. And yeah, I think there is a hunger for [those stories]. We are at a pivot point in our nation. We are looking at the past to figure out who we are and where we are going. When you read that list, I didn’t just hear it as films with black protagonists, I heard it as films grappling with our history and I think all of America is trying to grapple with who we are.

Boseman: It’s interesting being in films because we are watching this thing happen [black-protagonist films winning broad American audiences]. But I am hesitant to start talking about it, because I feel like if we talk about it, it’s going to stop happening [laughter]. I have to say it is not like the doors have opened up and everybody is cool with these films being made. It is still very difficult to find the money to get them made. It’s not like the entire culture in Hollywood has changed, it is just that there are a few, very smart, inspired people who have not taken ‘no’ for an answer.