Arts & Culture

Men and Ink

Globe Poster has been designing and printing its iconic show posters for nearly three-quarters of a century. Meet the Cicero family, the folks who keep Globe turning.

At 7:15 on a Wednesday morning, Bobby Cicero makes his way down Bank Street, between Conkling and Eaton, in Highlandtown. Balancing a cardboard take-out tray packed tight with coffee and a half dozen egg sandwiches, he stops at the door of a nondescript warehouse and fishes keys from his pants pocket.

A faint smell of ink wafts through the air and intensifies as Cicero pulls open the door. When he steps inside and turns on the lights, the office walls practically explode with color. From floor to ceiling, they are covered with bright, gaudy posters advertising soul revues, hip-hop extravaganzas, carnivals, gospel revivals, college homecomings, political campaigns, and swap meets. Welcome to Globe Poster, a Baltimore institution and one of the most celebrated poster companies in the world.

Cicero walks behind the counter, where a “100% Down On All Purchases, No Checks” sign states the firm’s billing policy. He unwraps a sandwich and sorts through a pile of paperwork. There is a fax for an Italian festival poster, as well as recent orders for DJ Hollywood Breeze and the Krazy Praise “Gospel Go-Go for God.”

The phone rings. “Hey, how are you?” Cicero says, as if greeting an old friend. He extracts a few paper-clipped pages from the pile of papers. “Yeah, I have it right here. . . Do you want it to read, Family Fun Carnival? . . Do you need this in Spanish, too? . . . I can fix it, no problem. . . I’ll dress it up. . . Let me get this in the works. . . I’ll have it for you, don’t worry.”

He returns the phone to its cradle. “It’s carnival season,” he says, knowing the seasonal work will keep him busy for the next few months.

Like the caller, many others will come looking for the classic Globe treatment—big, bold letters over splashes of Day-Glo color (orange, green, and red are the most popular) on a heavy stock that can withstand most weather conditions. “A lot of customers ask, ‘Why does it have to be so big and bold?'” Cicero explains between bites. “Well, if you’re trying to reach people driving past at 40 miles per hour, it has to be big and bold. That’s basically been our philosophy for all these years.”

Over the next hour, a half-dozen pressmen come through the door—each one is offered an egg sandwich—followed by various members of the Cicero family who take up positions around the shop. Bobby is the shop foreman, and he oversees the press work in the back; his brother, Frank, works out front, dealing with customers and sketching designs on notebook paper; Frank’s wife, Debbie, answers the phones and keeps the books; and Frank and Bobby’s brother, Joey, does the shipping and handling. Their father, Joe Sr., has been working at Globe since 1935, and although he’s officially retired, he comes in most days to help out. “They gave me a retirement party,” he’s fond of saying, “but I fooled them and came to work the next day.”

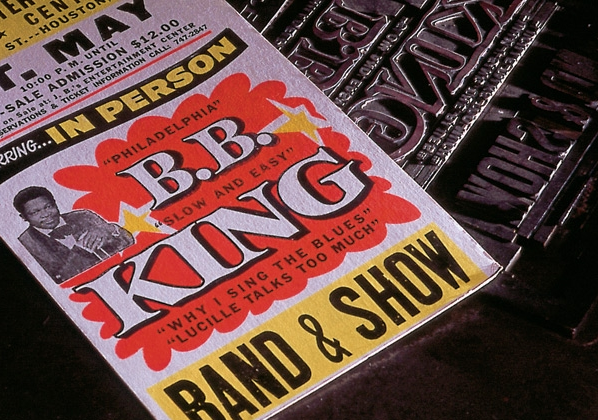

In Joe Sr.’s office, a copy of The Art of Rock sits on the desk. A gorgeous coffee-table book published by Abbeville Press, it features classic concert posters dating back to the 1950s.Globe is well represented, and

Joe Sr.’s copy has Post-Its bookmarking examples of the company’s best work. Of the Globe designs pictured, there’s an eye-popping 1957 “Biggest Show of Stars” poster for an early rock-and-roll revue featuring Chuck Berry, the Crickets, and Fats Domino; a poster for James Brown at the Apollo that promises “a show for the entire family”; and one for Ike and Tina Turner that, with flames surrounding sultry shots of Tina and the Ikettes, is decidedly less wholesome. “Tina Turner used to phone in orders herself,” says Joe Sr., pointing to the page. “She’d be on tour and call in to order posters for upcoming shows.”

Looking over his shoulder, Frank adds that lots of soul stars used to do the same thing. “I’d talk to people like Solomon Burke all the time,” he says, referring to the 1960s R&B great, “and dad will tell you that bandleaders like Count Basie used to stop into the shop when they were in town. They were good customers for us.”

“You weren’t a star until Frank and the people at Globe put your picture on a poster,” says Burke, when asked about the company. “Those were the good old days, when Globe printed thousands of posters for me.”

“I used to ride around with a stack of [Globe Posters] in my trunk,” recalls Ike Turner. “I used them for all our shows in the early days.”

“The posters gave you a little pride,” B.B. King has said. “You might be driving through by yourself and sneak a look at them and smile. Sometimes you would be passing through a town—let’s say Atlanta—and you would be stopping at a service station in one of the suburbs for fuel and directions. Someone would say, ‘Hey, you’re B.B. King! Hey, fellows, that’s B.B. King; I just saw his poster!'”

Now, those same posters, if you can find them, are worth thousands of dollars.With Globe’s now-iconic style inexorably linked to the glory days of R&B, and with deep-pocketed Boomers spiking demand for music memorabilia, vintage Globes are hot items. Old Globe posters, staple holes and all, have been auctioned at Sotheby’s and purchased for display at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum and the Memphis Music Hall of Fame. And the Rhythm and Blues Foundation recently called about acquiring some old posters. “It’s shocking,” says Bobby. “Who would have figured that our posters would be valuable someday? After all, they were made to look good hanging from telephone poles.”

Globe Poster was founded during a card game in 1929. As Joe Sr. tells it, Norman Goldstein, a wealthy New Yorker, and Harry Shapiro, whose family owned a printing business in Texas, were both at the table that night in Philadelphia. At some point during the game, Shapiro proposed going into business together, and Goldstein took to the idea. When the question arose about where the new company would be located, they took a map of the East Coast and randomly folded it. When it was reopened, the crease was on Baltimore. “So they started out in Baltimore,” Joe Sr. says, with a knowing smile and nod of the head.

The new company set up shop in the Smith Building on South Hanover Street with three letter presses and a cutter—”that we still use,” Frank notes. Despite fallout from the Depression, Globe prospered by printing for burlesque houses, vaudeville performers, movie theaters, and carnivals.

Joe Sr. was recently married and looking for work in the fall of 1935. The son of a Sicilian shoemaker, he’d grown up in South Baltimore, the fourth of six children. He knew about an opening at Globe, where his brother-in-law worked, and inquired about the job. “I started the next day,” he recalls, “cleaning and putting away type.”

He went on to perform virtually every job in the shop, and by the time Harry Shapiro’s brother, Norman, took over in 1954, Joe was foreman of the pressroom and the father of three young sons. He unfailingly refers to his old boss as “Mr. Shuh-pie-ro” and says it didn’t take them long to establish an excellent on-the-job rapport. “For twenty years, I was his right-hand man,” says Joe.

When Shapiro retired in 1975, he sold Globe to Joe. By then, the company had moved to the Candler Building at Market Place, and the younger Ciceros—who’d worked summers at the plant during their high school years—had struck out on their own. Joey became an accountant, Frank was a social worker, and Bobby worked at Black & Decker. But by the end of 1976, they’d all joined their father at Globe, full-time.

Since then, Globe has relocated twice; first, to a brick building on Byrd Street (that was also home to the National Federation of the Blind) in South Baltimore, and three years ago, to its present Bank Street address. Except for the hulking presses, which weigh as much as 13 tons a piece, the Ciceros moved everything themselves. “It practically killed us,” says 58-year-old Frank, during a tour of the print shop. “We’re not getting any younger, you know.”

With the presses whirring, a huge overhead exhaust fan humming, and a radio blaring the Who’s “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” he practically shouts to be heard. He points out an in-house promotional poster from the 1970s that was used to drum up business at print conventions and expos.With eye-catching panache, it promises “fast service and low prices” for a variety of posters, including “circus, rodeos, hell drivers, races, concerts, and bumpers.” When it’s noted that the phone number listed on the poster is still Globe’s number, Frank is unfazed. “That was a Mulberry number,” he says. “Mulberry five.We’ve had that number for at least fifty years.”

He walks past a few offset presses, the aforementioned paper cutter, a pair of Heidelberg numbering machines (for tickets), and a paint-splattered “clam shell”(for screen print work) that brings to mind paintings by de Kooning or Pollock. A pair of Miehle letter presses, dating back to 1907, quietly await repair. A five-gallon bucket of fluorescent orange ink sits beside a table with a pile of red shop rags on it. A bright green “O’Malley for Mayor” sign hangs on a nearby wall, along with recent concert posters forWillie Nelson, Rage Against the Machine, and Beck.

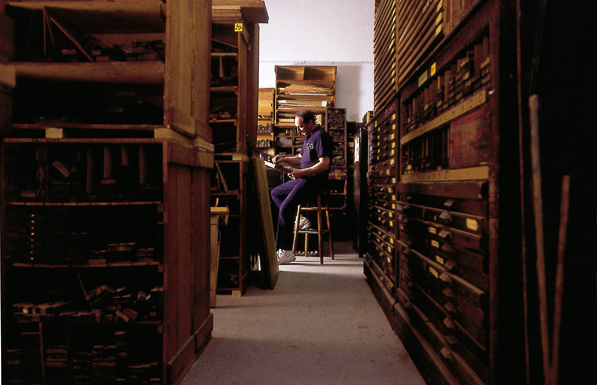

When asked how Globe’s distinctive style evolved, Frank and Bobby head for the composing room, where yards of hand-cut wood type are stored on shelves. This alcove used to be the domain of Harry Knorr, who designed posters at Globe for almost 50 years. When asked if any single person is responsible for the Globe “look,” Frank and Bobby respond in unison. “Harry,” they say, nodding in agreement.

In the mid-1950s, Globe began putting fluorescent inks behind its type, and Knorr started using multiple colors to highlight and define various parts of a poster. That’s one reason why Globe was such a good match for those old soul revues; it could draw attention to all the artists on a multi-act bill, and the music was bright and vibrant, just like the poster hyping it.

It was also common for Knorr to create custom letters reinforcing that vibe. “If it looks kind of weird, that was Harry,” says Frank.

And if the pressure of being creative during tight production schedules ever got to Knorr, he never let on. The Ciceros remember him pacing calmly, with a six-ounce Coke bottle in one hand, a pencil in the other, and a head full of ideas. “We’d be running around trying to get everything printed, and he’d be back here in his own world,” says Bobby. “He was always looking away, thinking. Then all of a sudden, he’d start sketching on a piece of paper, cardboard, anything. He had that sort of artistic temperament.”

Knorr’s design would be transferred to a block that was handrouted and cut to size by a woodworker making about $40 a week. The custom block was then incorporated into an overall design that also included more traditional block type. A nearby shelf holds various wood cuts created by Knorr, blocks with things like “Air Show,” “Fireworks,” “Farm Fair,” “Outdoor Frolic,” “Fish Fry,” “Jamboree,” and “Show Girls” cut into them.

Although his designs were fairly sophisticated for the Eisenhower era, Knorr never forgot that Globe posters were more utilitarian than artistic, and he passed that on to his disciples. “Harry always said that you should be able to read a poster in three seconds,” says Frank. “I think that’s true, and that’s how I judge our posters.”

It may not seem like much has changed since Knorr retired in the late-1970s, but Globe has actually proved to be quite versatile on the business front. The firm switched over from letter-press to offset printing in 1988, the year it began designing posters on a Macintosh computer. It also began printing just about anything, and over the years, the list has swelled to include restaurant menus, FBI shooting range targets, directional signs for real estate developers, spiral notebooks, ties, scarves, and T-shirts.

But more than anything else, it’s the Ciceros’ strong sense of family that shepherds Globe through the tough times. Lately, health problems have threatened the company’s existence, but always, the family pulls together to make the best of it. When Globe’s longtime secretary Barbara Carson (a cousin of the Ciceros’) suffered a stroke in 1998, everyone pitched in to make up for her absence. Debbie worked extra hours, and it wasn’t uncommon for Bobby to take a computer home at night to catch up on paperwork.

And when Frank fell ill from kidney failure in December of 2000, Bobby stepped forward to donate a kidney to his brother, who looks remarkably well these days. “It’s hard,” says Bobby, “but thank God we get to work with people we love and care about. You know, I think that sense of family also spills over to the other guys who work here. That’s the way we like it.”

Glancing around the shop, Bobby suddenly seems a bit antsy. Frank has left to tend to a customer at the front counter, Joey has been wrapping orders that need to be shipped, and Joe Sr. walks past on his way to the paper cutter. “I don’t want to seem rude,” Bobby says, “but I have a job to run.”With that, he tucks a shop rag into his pocket and hustles away, stepping in time to the mechanized rhythm of the presses.