At this point, I feel like I can write a biography of Wes Anderson, but not because I’ve read everything that’s been written about him. It’s because his films, all works of supreme nostalgia, affection, curiosity, and obsession, paint such a vivid picture of his childhood. Through The Royal Tenenbaums and Moonrise Kingdom, it’s clear that his parents were intellectuals, that there was always plenty to read and talk about around the dinner table, that there was a fusty vacation house where the family summered, a spare closet teeming with board games, and that he attended tennis camp or was a Cub Scout, or both. Through The Life Aquatic, we know that young Wes had a fascination with underwater adventure and Jacques Cousteau. Through Rushmore, we can glean that he was encouraged to stage elaborate plays and home movies. And now, with The French Dispatch, we can assume that there were coffee tables fanned with issues of The New Yorker.

As far as I know, no other magazine has ever before inspired such a loving and elaborate cinematic valentine. (Baltimore magazine: The Movie, your time has come!) But this makes sense for Anderson. I can imagine that reading The New Yorker felt like the height of urban sophistication to him, a young man growing up in Houston, Texas. It had the orderliness and fussiness that he loves so much. The clever, if occasionally precious covers and cartoons; the wonderful storytelling that would’ve sparked his imagination; the droll wit; the commitment to the highest standards of excellence that now marks his own work. And, of course, it had the legendary writers and editors: The French Dispatch closes with a dedication to William Shawn, Lillian Ross, James Baldwin, and The New Yorker founder Harold Ross, among others.

This film isn’t exactly about The New Yorker, of course, but rather a simulacrum called The French Dispatch that was operated out of Ennui, France, by a bunch of American expats, starting in the 1960s.

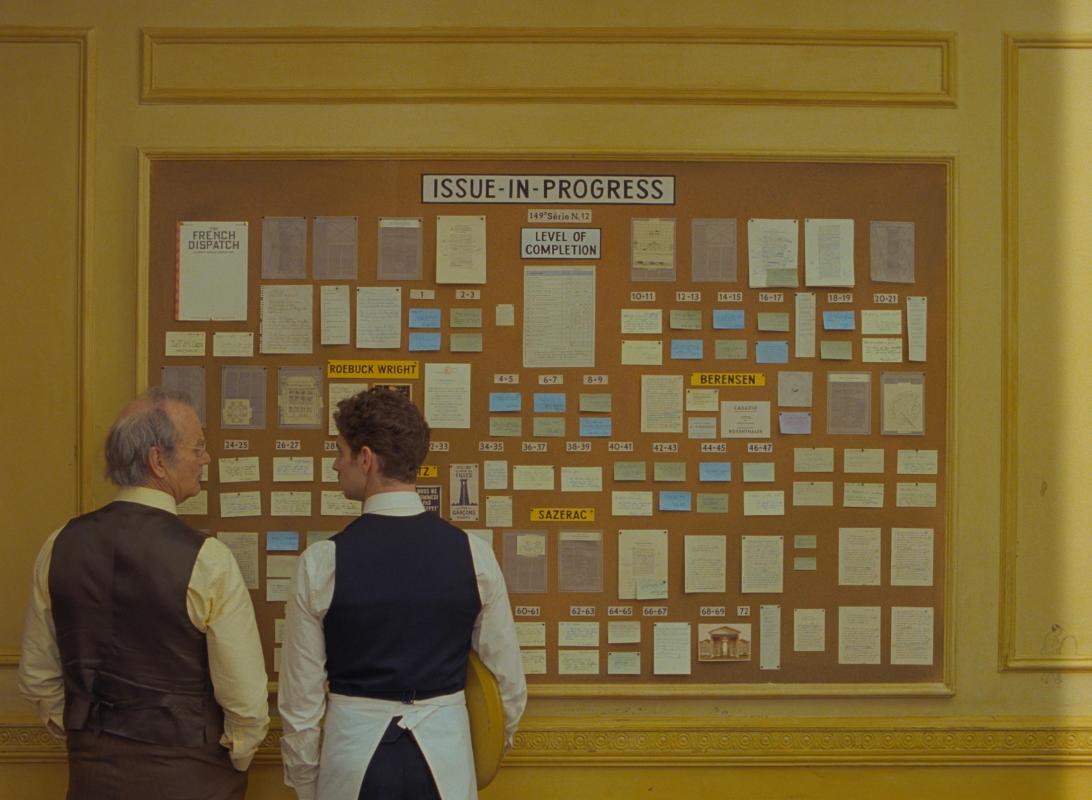

The anthology-style film is set up like a magazine itself, as well as a tribute to the magazine’s founding editor (Bill Murray)—a tough but loving man who championed quixotic geniuses, whose mottos were “no crying” and “just make sure it sounds like you wrote it that way on purpose” and who has just died of a heart attack when the film begins. The rest of the film reflects on some of the greatest stories that he had the pleasure to coax through to completion.

It starts with an amuse bouche of sorts, a “The Talk of the Town” proxy, featuring Anderson regular Owen Wilson riding his bicycle through some of the seedier neighborhoods and writing about them vividly.

Then we get into the good stuff. The first feature is an arts story, about an unstable genius artist (Benicio Del Toro), imprisoned for a brutal double murder, who paints to keep from going mad(der). His muse is a stoic prison guard Simone (Léa Seydoux), who strips down naked and poses acrobatically to inspire his abstract creations. The action takes place when an ambitious art collector (Adrien Brody) “discovers” him. His story is told by a grand dame arts writer who has seen some things, played with a flourish by Tilda Swinton.

The next section is about politics, the story of a group of young French would-be revolutionaries, led by the wild-haired Zeffirelli (Timothée Chalamet). Their approach to protesting seems to be “whatya got?”—and their story is chronicled by a stern, brilliant, unmarried writer (Frances McDormand), who takes a shining to Zeffirelli.

The final section, ostensibly a food feature, is about a famous chef cooking a meal for a police commissioner whose son is kidnapped, which sets off a wild rescue caper. This story is re-told by the James Baldwin stand-in (Jeffrey Wright, in a spot-on bit of casting), who is being interviewed on a snazzy ’60s-era set by a David Frost type played by Liev Schreiber.

It’s hard to describe how ingenious, creative, and bold this work is. At times, Anderson shoots in black and white, to suggest perhaps how the story might’ve appeared in print, then switches to painterly color. There are lively animated segments, drawn in a simple, elegant, New Yorker-ish style. There’s a snippet of a play within the film. And of course, the whole thing is packed with a level of painstaking detail that will encourage repeated viewings. Yes, Anderson’s films are directed with absurd precision. Some people have suggested his films are cold; I find them deeply emotional and stirring. They evoke childhood and memory and life’s greatest passions—what more could you want from a film?

The French Dispatch opens at The Charles and other theaters, on October 29.