Arts & Culture

On With the Show

A.T. Jones & Sons, the oldest costume shop in america, turns 150

a frigid winter morning at the warehouse of A.T. Jones & Sons costume shop in Mount Vernon, longtime owner and operator George Goebel is comfortably seated at a table and working on a headpiece—a finicky thing inside of which he’s wedged a plastic container for structure and is now sewing in seams. At 85 years old and using a walker, Goebel is still in this three-story building six days a week, albeit mostly restricted to his small makeshift workstation on the first floor. Just behind the front lobby of swords, bejeweled crowns, and suits of armor, he quietly toils away at whatever project needs attention at the business where he started in 1950 and took over in 1972—though he’ll tell you it took over him.

a frigid winter morning at the warehouse of A.T. Jones & Sons costume shop in Mount Vernon, longtime owner and operator George Goebel is comfortably seated at a table and working on a headpiece—a finicky thing inside of which he’s wedged a plastic container for structure and is now sewing in seams. At 85 years old and using a walker, Goebel is still in this three-story building six days a week, albeit mostly restricted to his small makeshift workstation on the first floor. Just behind the front lobby of swords, bejeweled crowns, and suits of armor, he quietly toils away at whatever project needs attention at the business where he started in 1950 and took over in 1972—though he’ll tell you it took over him.

“Sometimes I hear people come in the lobby and ask, ‘Mr. George—did he pass away?’ And I’ll say, ‘No, I’m still back here!’” he says with a chuckle as he lunches on leftover mashed potatoes and peas.

To his left, inside a large cage, is a chatty parrot named Oliver. Goebel was asked to bird-sit for a month while his owner took a holiday in Paris. That was 40 years ago. No stranger to birds, Goebel enjoys the company. He’s a renowned magician, after all, and has raised doves, ducks, robins, and even one crow, some of which used to actually live inside the warehouse. His beloved German shepherds would also roam the whimsical world of A.T. Jones, but these days it’s just Oliver and a scruffy little dog, Tazwell, though much else from the past remains.

Founded 150 years ago and now in its fourth location within Baltimore, A.T. Jones is believed to be the oldest continually running costume shop in the country, and it’s as storied as the plays and operas for which it provides wardrobes. Its history is revealed in row after row, floor after floor of past work—theatrical costumes that have been designed, sewn, labeled, and boxed away. Nearly half a chunk of city block along North Howard Street serves as costume storage and a testament to the shop’s longevity. Three floors and a basement at 708 North Howard (plus an additional four-story building next door that was purchased in the ’80s) houses thousands of articles of clothing, some of which are actual antiques, like military uniforms from past wars. Boxes and bins are stacked on sky-high shelves, stuffed with hats (top hats, pork pie hats, bonnets, tiaras), wigs, gloves, shoes, and miscellaneous accessories. There are even boxes labeled “tree limbs” for the characters that throw the apples at Dorothy in the stage adaptation of The Wizard of Oz.

the company survived the first world war and every war thereafter

Suits of armor line the lobby of A.T. Jones.

Entire rooms are devoted to specific operas and plays, their costumes stored in boxes that have been shipped across the country for productions and returned home to Howard Street. One area is used for washing and drying garments once they’re returned, and racks of petticoats, suits, and elaborate gowns from all periods and for productions as wide-ranging as Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and Tabasco: A Burlesque Opera line every spare inch of floor that’s not being used as workspace for the staff of seven.

This is what 150 years of costuming looks like.

The company survived the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904 (though its building on Baltimore Street did not, and nearly all inventory was lost). It survived the First World War and every war thereafter. It survived the Great Depression and, later, the advent of Party City and big-box stores, after once being the one-stop shop in town for Halloween costumes. And all the while, it’s been a home of sorts to generations of staffers, big-name patrons, and local customers, including a December client who followed in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps when he came in to rent a Santa suit for a holiday gathering. Through the years, it’s remained a family-owned and -operated business, though it switched families at one point.

masks in the front window act as a landmark for A.T. Jones & Sons costume shop, John Bernatitus and his dog, Tazwell, reams of fabric in the workroom, detail of

costumes, detail of a costume sleeve, a row of Santa suits, rented each year.

The company was founded under somewhat unusual circumstances. An artist named Alfred Thomas Jones won a painting contest hosted by what is now known as the Maryland Institute College of Art in 1861 and came to Baltimore from his North Carolina home to claim the $500 prize. But with the Civil War raging, he got stuck here. He eventually became a teacher at the school and, with an interest in fashion, began buying costumes from parades and masquerade balls, as well as extra military uniforms from the war, as a hobby. These would become the beginnings of his inventory when he opened shop in 1868, having discovered a business opportunity. His primary clientele were actors in the Baltimore theater district who were looking to piece together their ensembles.

As the name A.T. Jones & Sons implies, the shop was handed down to Jones’ son Walter Jones Sr. (his other son, Alfred, became a lawyer), who in turn handed it down to his son, Walter “Tubby” Jones Jr. Goebel worked under Jones Sr. from 1950 to 1952, then enlisted in the army. Jones Sr. died in 1955, so when Goebel returned from the Korean War, he began working under Jones Sr.’s wife, Lena, and Tubby, who never had the passion for the business that his forefathers had—and that Goebel had. With the help of his father-in-law, Goebel bought the shop in 1972. In 2009, a portion of the company was bought by Goebel’s son, Rick, who helped in the shop as a child and now essentially runs the place as its co-owner.

Like most everything, the “lending library of clothes,” as longtime staffer Mary Bova calls it, has had to evolve in order to survive, adapting to the changing needs and desires of its clientele. Not only have there been obvious changes with the times—like shipping costumes by UPS instead of the now-defunct Railway Express, or reconfigurations in their Santa beards, which used to be made with yak hair and dipped in kerosene—its focus has shifted, too.

At one point while A.T. Jones was still running the shop, he focused on renting used formal wear for people who couldn’t afford to buy it new—a novel idea at the time (they were the only shop in the city doing it). When Goebel started working under Jones Sr. in the ’50s, they were the only company in town renting Halloween costumes. Customers filled the lobby and overflowed onto the sidewalk. Staff handed out tickets as they waited in line. “Then Halloween became an industry,” Bova says. They still take customers by appointment if someone has a specific costume in mind, but they don’t open the shop for browsing.

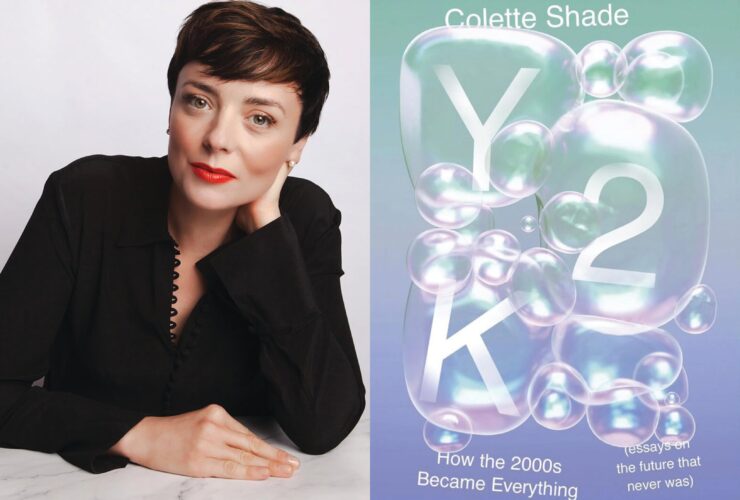

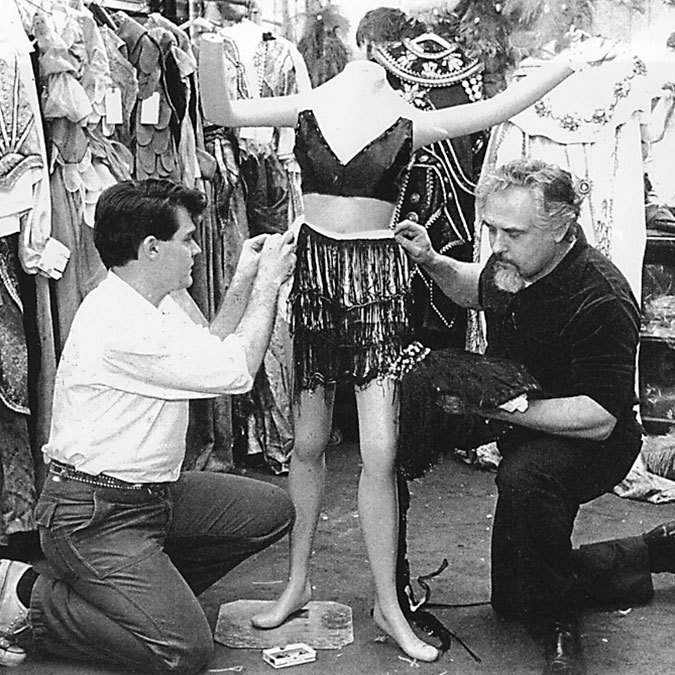

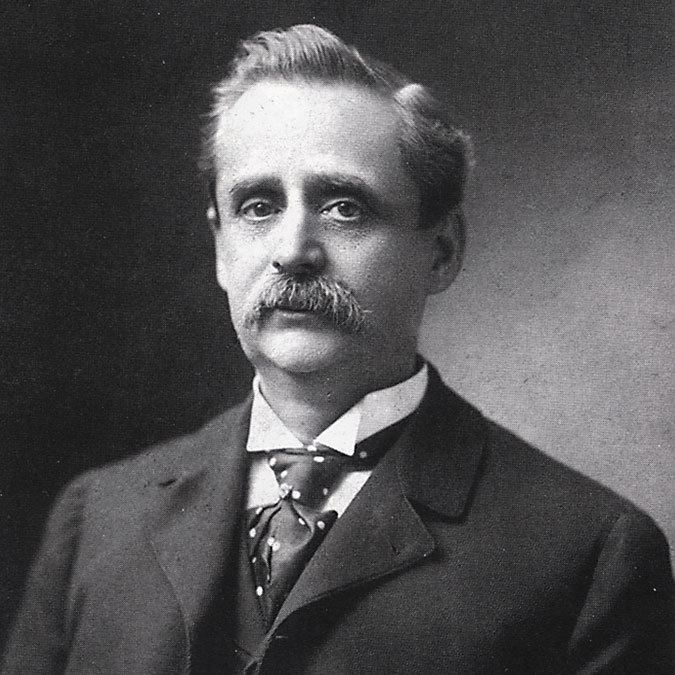

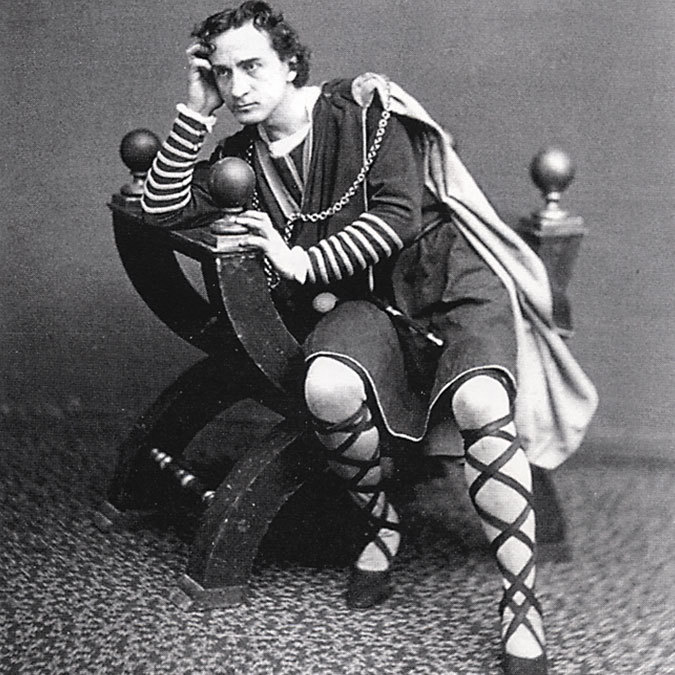

George Goebel, right, works with his son, Rick, Alfred Thomas Jones, founder of the company, the famous actor Edwin Booth, friends with Walter Jones Sr., antique buttonhole maker, Easter Bunny masks, stacks of bins filled with Santa beards.

To this day, A.T. Jones feels archaic in a magical sort of way.

Reams of fabric fill the second-floor workroom at A.T. Jones costume shop.

For a while, Goebel worked with Earl Dorfman and his son Rob—purveyors of wax figures—to clothe their pieces, some of which are still on display, such as figures at the John Brown Wax Museum in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, which opened in 1963. They’ve also made mascots—the original Baltimore Oriole and lesser-known mascot the General Motors crab were designed by the team at A.T. Jones. They’ve made costumes for the Gridiron Club’s annual theater show in Washington, D.C. (every year since 1888, in fact). And, on a somewhat bizarre note, they also “costume” undercover cops.

In the ’80s, Goebel presented a lecture to Baltimore police on disguise tactics—how to make themselves look like the bad guys with fake needle marks or altered facial features using makeup and other tricks. “We still have them as customers,” Bova says. “You can [imitate] scarring and bruising. None of them wanted to beat each other up just to go do their jobs.”

By the ’90s, theme weddings became popular. (People have also been known to rent suits of armor for their proposals.)

But these days, operas make up the vast majority of their business. Rick started leading the company into a new direction in the ’80s and has been making contacts with opera companies across the country ever since. Even as most major opera and theater companies have shifted toward using in-house costume shops, several smaller ones rely on A.T. Jones, even from many states away. Nearly all their business is from repeat customers and reputation.

“There’s a rapport that goes on when you have a client for 50 or 100 years,” says Goebel, adding that A.T. Jones doesn’t advertise or have a website. “We just recently got away from using two tin cans and a piece of string.”

He’s only half kidding: It wasn’t that long ago when workers used a literal rope to hoist items from the first floor to the second, before they installed a small iron staircase.

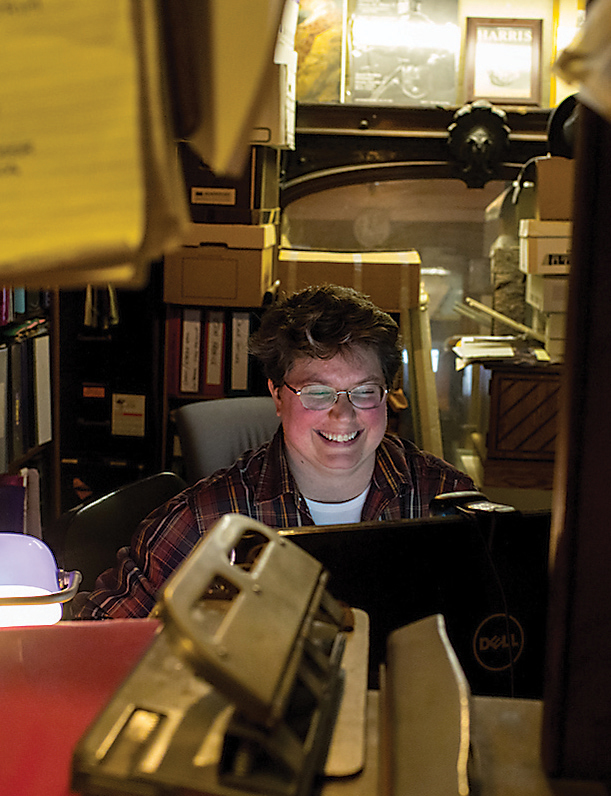

Monica Hibbert and John Bernatitus at work, George Goebel still works six days a week at the shop on North Howard Street

To this day, A.T. Jones feels archaic in a magical sort of way. An antique elevator lifts staff to the third floor (when they pull on its cable). The workroom, aka the entire second floor, acts like a functional museum, with some of the industrial sewing machines—most definitely the buttonhole maker—dating back 50 to 75 years. But it’s a vibrant place where fabrics of every color, pattern, and texture spill out onto tables, stretch over mannequin busts, are stored on long rolls, and overflow from bins.

Among the cast of characters here, each seems to have one thing in common: an early fascination with sewing that persisted throughout their lives. As a kid, John Bernatitus cut sheets to make his own clothes; now he is often responsible for creative solutions for unorthodox costumes, like a lamp dress for A Christmas Story: The Musical and fish that are able to swim across the stage in Disney’s The Little Mermaid. Bessie Gaylord learned the art from her mother and has made a living as a seamstress at various factories and shops—including her own, Bal Masque Costumes, where she made outfits for early John Waters film characters, including Divine’s shoplifting dress from Pink Flamingos (“Those were his weird days,” she recalls, “I mean his really weird days”). Monica Hibbert’s mother was a designer and dressmaker in her native Jamaica before starting at A.T. Jones, and Hibbert followed close behind at the shop in 1989 and still works there five days a week.

Then there is the family. On staff part-time is 96-year-old Helen Dangler, Goebel’s wife’s aunt. “I think it has helped her live longer,” he says. “She really has a purpose when she comes here.”

And, of course, there’s his son, Rick, who is the backbone of the company now, working closely with directors to design the elaborate costumes, as evidenced by his drafts of patterns strewn across a nearby table.

longtime employee Mary Bova amid the usual clutter of A.T. Jones, mannequins in the workroom.

One of those directors is Samuel Mungo. When he moved to Baltimore in August and became managing artistic director of Peabody’s opera program, Mungo was ecstatic to learn that A.T. Jones costume shop was located just a few blocks from the conservatory. “They’re relatively famous in the opera world,” says Mungo, who has been involved as an actor, scholar, and director of opera for more than 25 years.

For his first production at Peabody, Donizetti’s The Elixir of Love, he worked with Bova and Rick. He wanted to update the story to be set on a 1960s college campus and had a specific look in mind. “One of the characters was like a second-wave feminist, so I wanted a sort of Gloria Steinem feel to her,” he says. “I was going to scrap two of the character ideas because they weren’t really viable, but Rick said, ‘No, I think that’s a great direction to go.’” They made it work. Along with the Steinem type, both the football player and hippie of Mungo’s imagination came to life onstage with every style and stitch in perfect place. “The right costume makes the show,” says Mungo. “And also, the right costume makes the actor. [Students] have that added level of comfort when everything is fitted and done right here.”

When The Elixir of Love finished its run, the costumes were returned, washed, dried, and packed into storage, where they’ll stay until they’re called back into the light of day again. And then they’ll be resized, adjusted, and shipped to another production company. And maybe later the football player will be rented as a Halloween costume, or the hippie will return when a fiancé requests a ’60s-themed wedding. The life cycles of the costumes have officially begun inside the wonderful world of the A.T. Jones shop.

And Goebel has had a front row seat to it all. Recalling the long days he used to pull years ago, Goebel’s brown eyes twinkle and his smile widens through a silvery-white goatee. “Even though you were tired, you really enjoyed it,” he says. “I’m getting tired now, but I still really love it.”