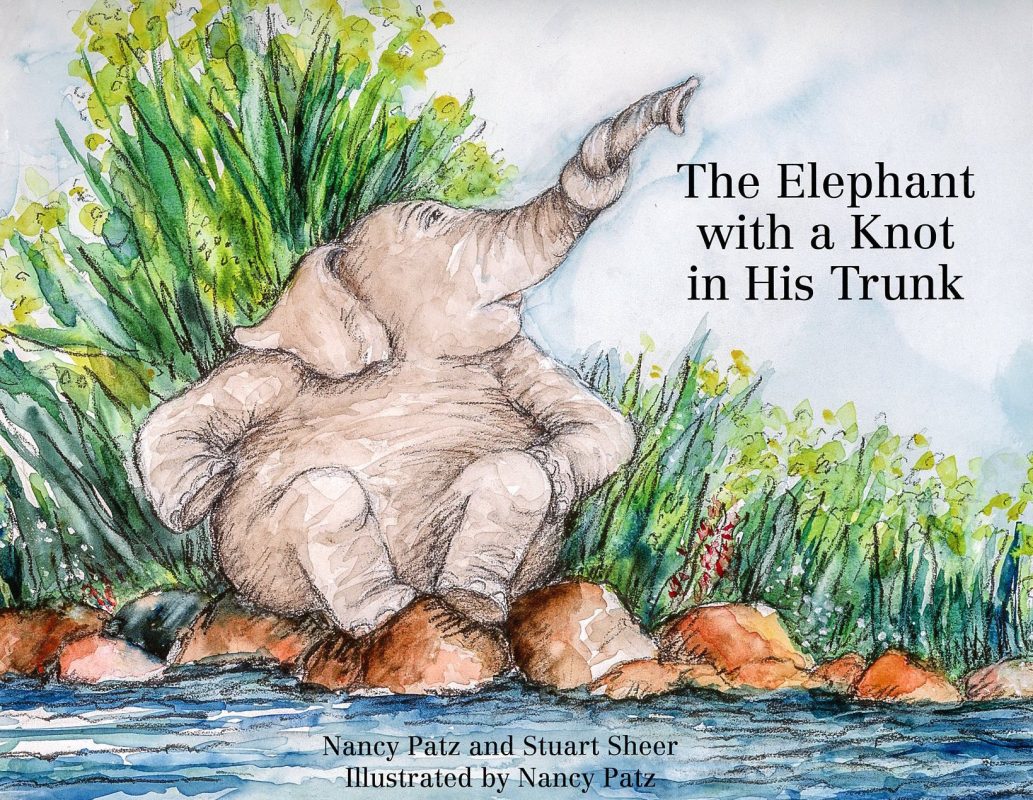

The Elephant with a Knot in His Trunk is a picture book with talking animals, true, but all ages can glean some wisdom from its pages, as it’s charged with truths about how we overcome what we perceive as our shortcomings, and ultimately how that shapes our identity. The story is elegantly told and illustrated with a lushness of loose, textured graphite lines and rich watercolor that emotes the wildness of the jungle.

Stuart Sheer, an orthodontist practicing in Mount Airy and Finksburg, was inspired to write a story after numerous trips overseas helping children with cleft palates (an orthodontist is needed to make a diagnosis and treatment plan). He witnesses firsthand how these kids are bullied and in some respects separated from the rest of society because of their inability to speak clearly. In working with surgeons to repair cleft palates, he understands how dramatically those changes affect children’s confidence—and he thought a book might help in the healing process as well.

He first wrote about a girl with a cleft palate and had planned to publish it and give it to clients, but the story took another shape when he began collaborating three years ago with Pikesville children’s book author and illustrator Nancy Patz to develop the book, which they self-published and released in November.

“It’s easier to show emotions through animals sometimes,” Patz says (though she still uses herself as a model in the mirror).

Kofi is an elephant born with a knot in his trunk, as the title suggests. This not only limits what he can do (even drinking proves challenging), but makes him a target for bullying. He goes to great lengths—indeed, risking his life—to undo this knot. Eventually, a doctor (a monkey) operates on him and is able to untie the trunk, leaving behind a kink but allowing Kofi to do eat, drink, and trumpet-call like the others. Meanwhile, he faces an agonizing decision when he spots his biggest nemesis drowning in a whirlpool and has to quickly decide whether to try to save him. Kofi lends his trunk, pulls Big Ebo to shore, and realizes his value in a way he hadn’t previously.

“The book applies to people without disabilities, too,” Dr. Sheer says. “All of us feel somewhat not whole. . . . People say it’s timely, but bullying has been going on forever.”

“Who has not been outside the circle?” Patz echoes. “Your hair’s too straight, your hair’s too curly, you’re too smart, you’re too dumb. . . . But this book is also for the people who are picking on others, to show what it feels like. What Stuart contributed, in large measure, was his complete empathy with his patients. He wanted a book to ease their emotional distress.”

In one scene, Kofi’s anxious parents watch from the edge of the jungle as a nervous Kofi talks with the doctor who is about to operate on him. Dr. Sheer has watched the human version of this scenario play out again and again.

As nurses lead a child away from the parents for the procedure, both children and parents are apprehensive. They all have to trust, quite often through a language barrier, that the surgery will help. Sometimes families travel for weeks from remote locations to have the surgery performed.

Dr. Sheer and Patz chose to keep a curl in Kofi’s trunk after his operation to reflect the imperfections that occur in real-life surgeries.

Anti-bullying groups and others are interested in using the book for educational purposes, Dr. Sheer says, which came as a pleasant surprise, as he has done little to promote it.

But perhaps the most rewarding feedback came by way of a class of first-graders who was recently given the assignment to make a drawing about the book and tell what lesson they had learned from it. The teacher showed Dr. Sheer the students’ images, with taglines like “Be a buddy, not a bully” and “Treat people the way you want to be treated.”

“We’re responsible for each other,” Patz says. “That’s really what Kofi proves.”