Arts & Culture

Good Grief

Local artist Peter Bruun found new purpose after the death of his daughter.

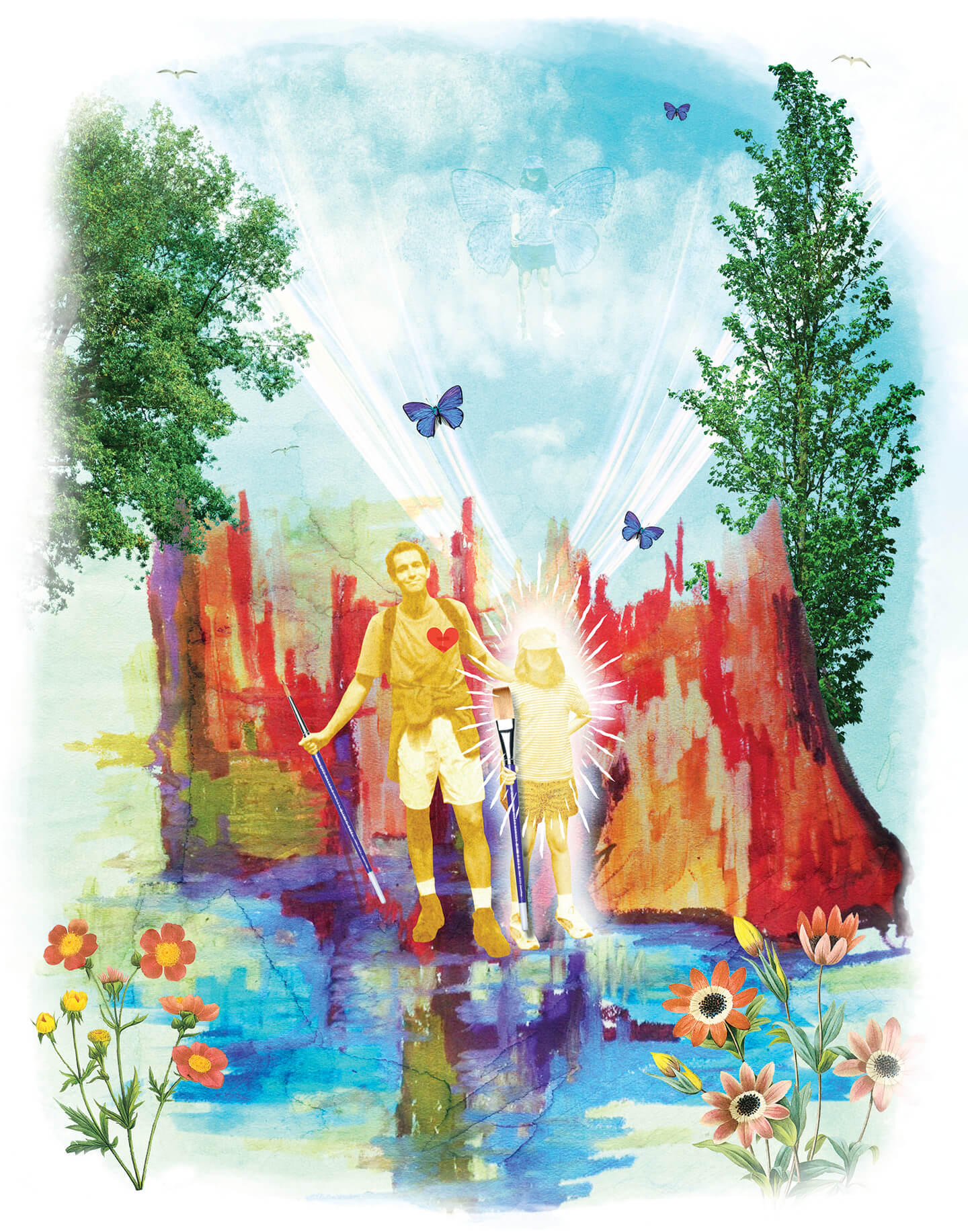

– Illustration by Sonia Roy

The call came around 9 a.m. on February 11, 2014. Peter Bruun and his wife, Serafina, were settling into a getaway at Deep Creek Lake. Peter, the Baltimore artist behind Bruun Studios, had been working hard and needed a break. So the previous evening, the couple had driven from Baltimore to a picturesque B&B adjacent to a state park. Before the phone call came, they’d eaten breakfast and lingered over coffee and The New York Times.

At one point, Bruun had commented on an article that keenly interested him and his wife. Titled “Heroin’s Small-Town Toll, and a Mother’s Grief,” it was about a woman coping with the death of her 21-year-old daughter, who had overdosed near Minneapolis. The mother recalled how her son had phoned and asked, “Mom, are you sitting down? You need to. It’s bad.” How she hadn’t touched a thing in her daughter’s room, which became something of a shrine. How she regretted that she hadn’t been more empathetic when her daughter was alive.

“This is so tragic,” Bruun remembered saying to Serafina. It was especially newsworthy because Philip Seymour Hoffman had died of a drug overdose the previous week.

Bruun and Serafina went back to their room to put on snow gear. That’s when his phone buzzed. The call was from CooperRiis, the North Carolina treatment facility and healing community where his daughter Elisif, age 24, had been living for the past three months. Bruun answered, and it was Jeff Byrd, the then-managing director of the Mill Spring campus—known as “the farm”—where Elisif was a resident.

“I am very sorry to tell you,” Byrd began haltingly, and during the brief pause, it flashed across Bruun’s mind that Elisif may have been kicked out of the facility. He felt a stab of frustration and dashed hope. Elisif had struggled with addiction, but she seemed to be making solid progress when he and Serafina had visited CooperRiis after the holidays.

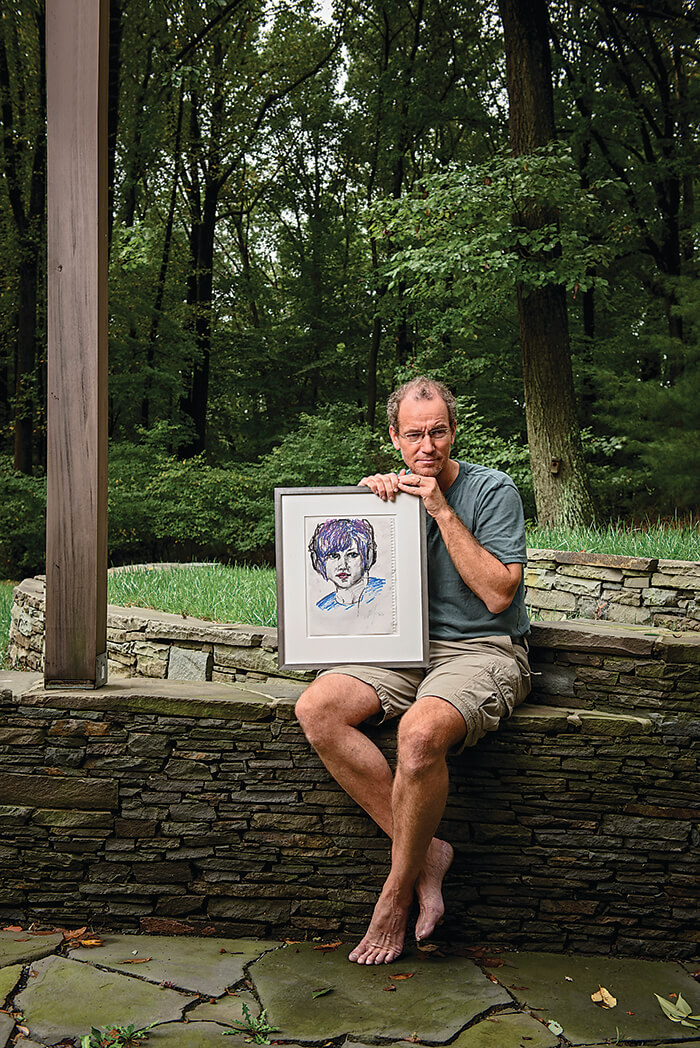

Artist Peter Bruun with one of his daughter Elisif’s self-portraits outside his home in Glen Arm. —Photography by Mike Morgan

Then, Byrd said, “Your daughter passed away last night.” He expressed his condolences, and added something about Elisif being found unresponsive in her room, with a syringe and “a substance.”

Bruun’s eyes welled instantly with tears, and his breathing became little more than gasps. His frustration, and its familiarity, gave way to a previously unknown chasm of anguish, but he managed to communicate what had happened to his wife, who was watching him intently, and finish the call with Byrd. Then, Bruun and Serafina held one another as their crying crescendoed. He slid to the ground and beat the floor with his fists.

An hour or so later, dazed and in shock, they found themselves tromping across the frozen, snow-covered lake. Following snowmobile tracks, they trekked a few miles out, stopping to cry every few minutes, before coming to a crossroads on the trail.

In the distance, the path looked shadowy and dim, and led to a bridge. In his mind, Bruun saw Elisif disappear under the bridge, which he couldn’t see past as it was too dark.

As the reality of parting with his daughter became more apparent, Peter forced himself to move on; he and Serafina headed in the other direction, where the path was lit with sun.

Elisif was the Bruuns’ first child, born March 20, 1989, at Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore. Her name is a Scandinavian variation of Elizabeth. Elisif was a precocious, headstrong, and unusually creative child. At 6, she was diagnosed with diabetes and took daily insulin shots. At 7, she announced to her parents that crying was for babies and vowed she was done with it—and they never saw her shed tears again. A voracious reader, she’d curl up with her Harry Potter or Game of Thrones books all day if given the chance. She loved dressing in costume.

Elisif went to The Park School of Baltimore and circulated amongst a group of friends Bruun recalls as “outside-the-box thinkers, down to earth, and real.” She distinguished herself as an art star, skillful at drawing, painting, jewelry making, fiber arts, and photography. She sometimes made films with her younger sisters, Sophia and Kayla. “Elisif was spectacular,” recalls Kirk Wulf, her English instructor and academic adviser at Park. “She was so full of life and brimming with big ideas.”

“She was a creative genius with anything she touched, totally artistic,” recalls her sister Sophia.

In that way, Elisif took after her dad. A native of Denmark, Bruun has been a fixture on the local art scene for decades. He grew up in New York City, studied art history at Williams College in Massachusetts, and moved to Baltimore in 1987 for grad school at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), where he earned a master’s degree from MICA’s multidisciplinary Mt. Royal School of Art. He has been in Baltimore ever since, making his own art and facilitating community-engaged, issue-oriented exhibitions—including Art & Addiction (2006), Black Male Identity (2011), 30 Women, 30 Stories (2011), and Autumn Leaves (2014)—at what is now Stevenson University, The Park School, and numerous other venues.

His work has been recognized with “Best of Baltimore” honors in Baltimore and as a “Top 10” in City Paper. “I am amazed by Peter,” says recently retired Baltimore Museum of Art director Doreen Bolger, who collaborated with him on 2010’s Baltimore Inspired by Poe exhibition at the BMA. “His work actually transcends the local arts scene and affects the city at large.”

Sitting outside Starbucks in Mt. Washington, Bruun recalls that during her senior year, Elisif distanced herself from her core group of friends, telling him, “They’ve all gone crazy getting into colleges. It’s no fun anymore.”

“Well, good for you,” Bruun thought. “You have your feet on the ground, and you’re thinking independently.”

Elisif was a precocious and headstrong child who loved to dress in costume and play with her two younger sisters.

But there were other indications that something was amiss. Wulf remembers that she was increasingly prone to “bullshitting and sidestepping school responsibilities.” Elisif took to staying out later. Sometimes, she drank and came home around dawn, with little or no explanation. Still, she was never argumentative, showed up where and when she was needed, and often lingered at the dinner table. “At the time, we didn’t see her overall behavior as alarming,” says Bruun. “We considered it somewhat typical for a teenager. But as parents, we also tend to see our children as the angels we love.”

He was a little sorry when she chose to attend the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston over the more promising Art Institute of Chicago, or a broader-based liberal arts college, but he supported the decision. During her second year in Boston, however, Elisif became aloof. When her parents were able to reach her, she inevitably wasn’t feeling well; it seemed she always had the flu. Her parents grew concerned, though they didn’t suspect the cause.

They were later devastated to learn their daughter was addicted to OxyContin. Sophia, a confidante of Elisif’s, figured out her secret, and alerted her parents. “We were so naïve,” recalls Bruun. “I’ve never even smoked pot and hardly know what it smells like. I am the straightest edge in the world. So we were dealing with something way out of our zone of experience.”

The next six years were a whirlwind of searches for information and resources, interventions, breaches and reconciliations, wrecked vehicles, unlikely stories and outright lies, plans for fresh starts, rehab stays, hospital visits, haggles with insurance companies, misgivings about questionable acquaintances, stretches of silence, and, always, a foreboding sense of fear for Elisif’s safety. In the fall of 2013, she entered CooperRiis for treatment.

“In some ways, we had already rehearsed her death, because we had experienced the fear of her being dead a number of times,” says Bruun. “We also were aware that if she neglected taking her insulin, that could be fatal, too. But it’s like doing Lamaze before having a child in that it doesn’t fully prepare you for the reality of childbirth. All of that rehearsal did not prepare us.”

Bruun’s initial response to his daughter’s death echoed the work he’d been doing in the local art scene for years: He worked with the community—in this case, the CooperRiis community—and, within days, had organized a gathering with CooperRiis staff. The memorial service at the facility was for family, friends, and staff members who knew Elisif, and featured music, poetry, artwork, and poignant remembrances. Bruun recalls it as painful but also somewhat magical “because the person everyone at CooperRiis remembered was similar to the person we knew before she got sick.”

Gathering up Elisif’s belongings, Bruun came across a journal, in which she confessed: “I feel guilty because I have lied to my parents so many times—I feel so guilty and I don’t know how to stop.” Another time she wrote: “Hi inner child. I don’t know if you’re still alive. I’m worried that I’ve killed you.” And later: “I still love heroin. I just hate everything that comes with it.”

Elisif loved nature, and it brought solace during difficult times in her life.

Among her possessions was a striking self-portrait she’d done in charcoal and pastels. Bruun noticed it was signed, which he found significant because it had been years since she’d signed a piece of her artwork. The last photograph of her is a cellphone selfie taken with three friends at CooperRiis, the group bathed in oversaturated streaks of rainbow color radiating from a bright light overhead. Elisif is grinning so widely that her eyes are starting to crinkle.

In addition to the loss, Bruun also had to grapple with the circumstances of Elisif’s death. While in North Carolina, he met with Polk County detective B.J. Bayne, who’d found evidence that the drugs Elisif used had been mailed to her. (At CooperRiis, Elisif was allowed to receive unopened mail.) Bayne explained that, under North Carolina law, if a person provides controlled substances that lead to someone’s death, he or she can be charged with murder. Bayne figured it was a dealer, anticipated going after whoever mailed the drugs, and asked Bruun how he felt about that. Bruun responded that if the suspect turned out to be a dealer profiting on the illness of others, prosecution would be appropriate. But if the suspect was an addict like Elisif, he hoped treatment options would be pursued.

Back in Baltimore, Bruun started on a series of powerful abstract drawings (he says the images came to him almost immediately after Elisif’s death) and thought about what to do next. “Do I pretend this didn’t happen?” he asked himself, but he also abhorred the possibility of rumor and innuendo. After getting the okay from family, he blogged about Elisif’s death on the Bruun Studios website and shared it with the 3,000-plus people including colleagues and friends on his newsletter’s email list. “I pushed send and felt so naked,” he says of the February 27 post.

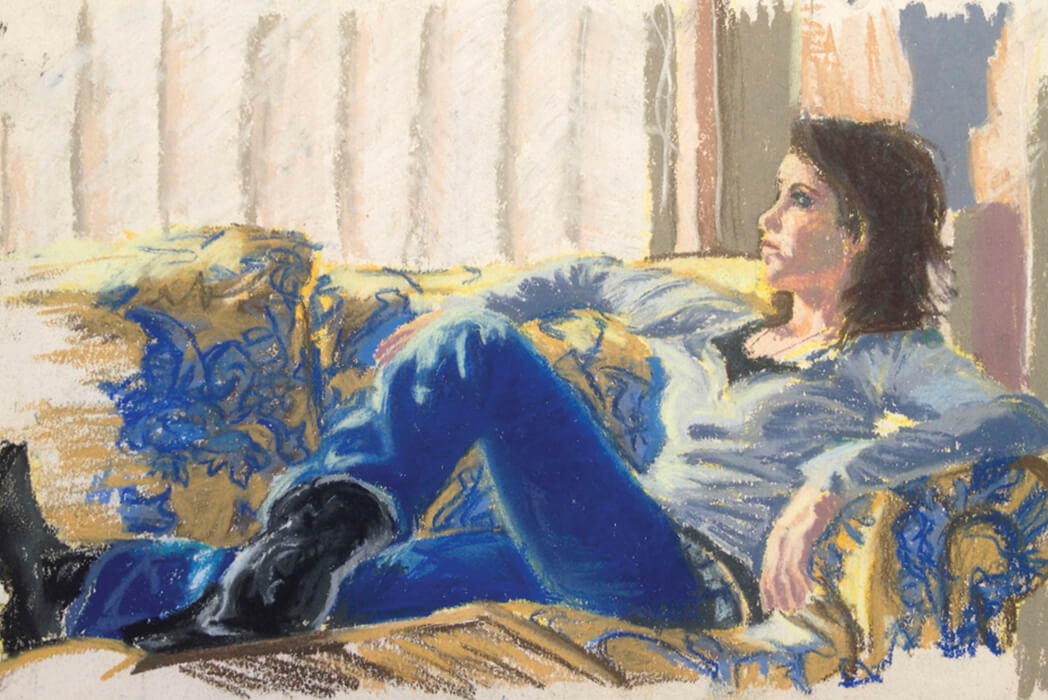

Elisif was exceptionally creative, excelling in painting and other creative arts.

Titled “A New Day,” the post lamented the loss, but also the social stigma surrounding addiction. It hinted at a new vision for the future, an approach infused with “an attitude of compassion . . . of humanity . . . a humane outlook that perhaps bespeaks the dawning of a new day . . . The memory of Elisif—and so many others like her—deserves nothing less than this new day.”

His email and phone “exploded.” The response, and the outpouring of support at a later memorial event and exhibition of Elisif’s art at The Park School, showed Bruun the need for a new approach to addiction. “I knew I had to do something,” he says. “I just didn’t know what.”

Then, Polk County authorities announced they had made an arrest.

The news broke on WLOS News13, the ABC affiliate in Asheville, on September 2. “A Pennsylvania man has been extradited to the [Blue Ridge] mountains to face a murder charge,” the anchorman stated on that evening’s newscast. “Deputies say Sean Harrington mailed a package of drugs to a woman in Polk County, Elisif Bruun, that ultimately killed her,” continued the co-anchor. “He is now charged with second-degree murder and selling drugs.”

Under a “Second-Degree Murder” banner, Elisif’s driver’s license photo and a picture of Harrington—with a mustache and receding hairline that aged him beyond his 25 years—flashed on the screen. The segment cut to a reporter telling viewers this was the first time Polk County authorities had ever extradited someone from outside the state for murder, before showing Harrington, handcuffed and dressed in gray-and-white-striped prison garb, being led from a squad car to the courthouse. The reporter explained how Detective Bayne had pieced together evidence leading to Harrington in Philadelphia, and district attorney Greg Newman warned: “People that provide [drugs], in this case heroin and cocaine are what we’re alleging, and providing it through the mail, cannot escape legal responsibility wherever they are in the United States.” It was noted that Harrington’s bail was set at $450,000.

The last-known photo of Elisif, middle right, before she died.

The local newspaper reported much the same story but added that the Bruuns had told Bayne they would attend Harrington’s trial. “They don’t want this to happen to any one else’s daughter,” the detective said, implying that Bruun and the family supported the aggressive prosecution. Both reports failed to mention that Elisif and Sean Harrington were actually friends.

After learning this himself, Bruun reiterated his position to Bayne via email. After acknowledging the criminal justice system’s importance with regards to the drug epidemic, he told Bayne: “I hold this young man as little to blame for Elisif’s death as I hold Elisif: in each case, an evil disease is at play; in each case, a young person is more victim than perpetrator. . . . I feel nothing but compassion for this young man in jail, and I personally hold him unaccountable for Elisif’s passing. I do not want him punished—I want him to receive treatment, or at least the option of treatment. He deserves the chance to get well.” Bruun did not receive a reply.

He said the same thing in an article that ran in the Philadelphia Daily News, adding that Elisif “would be horrified to know that this young man had been arrested.”

A self-portrait.

Sitting in the living room of their South Philadelphia row house, Sean’s parents, Michael and Michele Harrington, recall reading the Daily News piece. “I was in tears,” says Michael Harrington, who works for the City of Philadelphia administering drug tests to employees. “I didn’t expect that reaction from Bruun. I thought he would be angry, but it turns out that he understands Sean’s struggles.”

Sean was also a creative kid and an average student. His parents noticed how he would pick up his older brother’s guitar and absentmindedly play along to whatever he was watching on TV. Michael enrolled him in the Paul Green School of Rock, the country’s first School of Rock program, where Sean excelled at playing classic rock tunes by the likes of Black Sabbath and AC/DC. He appears briefly in Rock School, the 2005 documentary film about Green and his program. “It’s his claim to fame,” says Michele Harrington. “Well, it’s one of his claims—the good one.”

Sean wrote his own music and put together the bands Whiskey Livin’ and The Blessed Muthas to play original material. His mother points out a spiral notebook with Sean’s hand-drawn sketch for a Whiskey Livin’ logo in it. His father gestures to the wood floor Sean installed and the kitchen ceiling he put in for them when he worked construction and learned home-improvement skills.

But Sean also, they suspect, picked up a drug habit from co-workers. He grew increasingly remote and sickly. He had a guitar stolen, was beaten up a few times, and offered baffling explanations. He was argumentative and fought with his brother.

Similarly, Elisif had become increasingly combative with her sister Sophia during a visit home from college. Sophia knew Elisif had tried drugs and suspected she was now abusing them. She shared her concerns with her parents, who responded immediately by conducting an intervention. Ultimately, Elisif went to rehab.

When insurance wouldn’t pay for more than a month of inpatient treatment, Elisif was released and, eventually, relapsed. After a rough stretch, she moved near family in upstate New York for a fresh start. However, she quickly slipped into old habits and settled in Maine with a boyfriend, who turned out to be an addict as well.

The Harringtons also had figured Sean would benefit from new surroundings, and, in 2011, he left Philadelphia for Maine, where Michael’s stepbrother owned several restaurants. “We figured we’d send him up there, where it’s safe,” Michael Harrington says. “It turned out that there are plenty of drugs up there, too.”

From an early age, Elisif distinguished herself as an art star, skillful at drawing, painting, jewelry making, fiber arts, and photography.

After a stint in rehab in 2013, Sean met Elisif in Maine. In fact, when Sean returned to Philly later that year, Elisif dropped him off on her way to Baltimore. “Sean talked about her a lot,” recalls Michael Harrington. “He considered her a real friend, because they were both artistic. She was one of the people he talked about positively.”

“They were similar spirits,” adds his wife.

One day, the Harringtons found Sean inconsolable. He told them Elisif had died from a drug overdose. “Until then, we didn’t know she had an addiction problem, too,” says Michele Harrington. “Sean cried on the sofa for two days.”

His condition deteriorated; a few months later, he was living in a box under the Interstate 95 overpass not far from the Harringtons’ home. When Michael Harrington got a call from a homicide detective, his immediate reaction was, “Sean’s dead, isn’t he?”

His relief that Sean was alive gave way to disbelief that he was charged with Elisif’s murder in North Carolina. “We were stunned,” he says. “He’d never been in serious trouble and never hurt anybody.”

“Mostly, he played music,” says Michele Harrington, “but heroin changed everything.”

Now, the Harringtons fear they, too, may have lost their child for good. They can’t afford to make regular trips from Philadelphia to North Carolina and, besides, notes Michele, visits at the Transylvania County Detention Center, where Sean is being held, last only 30 minutes. They rely on phone calls and letters to stay in touch.

As of press time, Sean’s trial date had not been set. If convicted, he faces more than 50 years in prison.

Examples of Elisif’s work and a photo of her as a child showing her adventurous spirit.

The realization that the difference between victim and suspect was so slim compounded the tragedy for Bruun. That, coupled with the overwhelming reaction to the “New Day” blog post, convinced him of the need for a big response. Serafina and their daughters, though grief stricken and continuing to process Elisif’s death, gave him space to proceed. With Elisif as his muse, Bruun’s mission was clear: “to challenge stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness and addiction, making the world a more healing place.”

Since Bruun announced plans for the New Day Campaign at Area 405 last November—with Michael Harrington by his side—his ambitious initiative now includes 15 art exhibitions and 60 public events related to addiction and mental illness. Running through December 31, New Day will exhibit the work of dozens of artists—some of them also recovering addicts—at venues from MICA and Stevenson University to New Beginnings Barbershop and The Institute for Integrative Health. Related events include a film series, book club, information sessions, music and storytelling, community conversations, and talks with the likes of Leslie Jamison (author of The Empathy Exams), Dr. Leana Wen (Baltimore City Health Commissioner), Maria Broom (dancer/actress/author), and Dr. Robert Schwartz (Friends Research Institute’s medical director).

Between sips of coffee at Starbucks, Bruun says he hopes such broad-based programming can usher in a paradigm to replace the War on Drugs and the mass incarceration that’s come with it. That approach has, he believes, amplified stigmas of addiction and related mental illness. “If we didn’t judge those who do drugs as we do, Elisif would still be alive,” he says. “If Elisif, for instance, had a brain tumor, she could come to us and say, ‘My vision is blurry, I’m concerned.’ But she could not come to us and say, ‘I have fallen in love with opiates for some reason. It kind of scares me.’”

At CooperRiis, Elisif worked on herself more than anywhere else. She saw a psychiatrist, nutritionist, therapist, and job supervisor, and worked in the kitchen. Genetic testing showed a predisposition for a higher risk of opiate addiction. The revelation seemed to help her understand her desire for drugs such as heroin. “It helped with her acceptance of herself,” says Bruun. “As a parent, I felt like it was the sun coming out in terms of recognizing who she was.”

So when Bruun is asked why he isn’t suing CooperRiis, he smiles ruefully. “I was actually grateful to them,” he says. “I knew it was a risk sending Elisif there, but it was a risk anywhere. But I saw them doing really good work and know her relapse could have been triggered by anything.” (A CooperRiis representative declined to comment on past or present policies, citing the legal proceedings.)

The way Bruun has channeled his grief and anger into something that celebrates his daughter’s life has encouraged others to join his movement for change.

“The scope and content and urgency of Peter’s campaign immediately compelled me,” says author Jamison, who has worked on a book about addiction and recovery for the past five years and thought a great deal about “how people make sense of addiction and try to narrate the process of healing.” It was like she couldn’t imagine not being involved in the project. “Peter’s sincerity, his intelligence, his genuine and nuanced openness—made me feel, in my gut, that I wanted to be part of what he was doing.”

“It’s inspiring to see someone take the high road, in the face of personal loss,” says Doreen Bolger. “Peter’s efforts to reshape tragedy into something positive and useful is a metaphor for all of Baltimore and even the nation, considering the challenges we face at this moment.”

Bruun drains the last of his coffee and stands. “They say addiction is a family disease, but it’s really a community disease,” he reflects. “We all need to find ways to love the addicts in our lives, which is really hard. We feel like it’s being done to us, but it’s not. We’re the collateral damage, but they are the victims that are too often stigmatized.

“I understand that now, and it is the driving force behind New Day. That was the last gift Elisif gave me.”