Arts & Culture

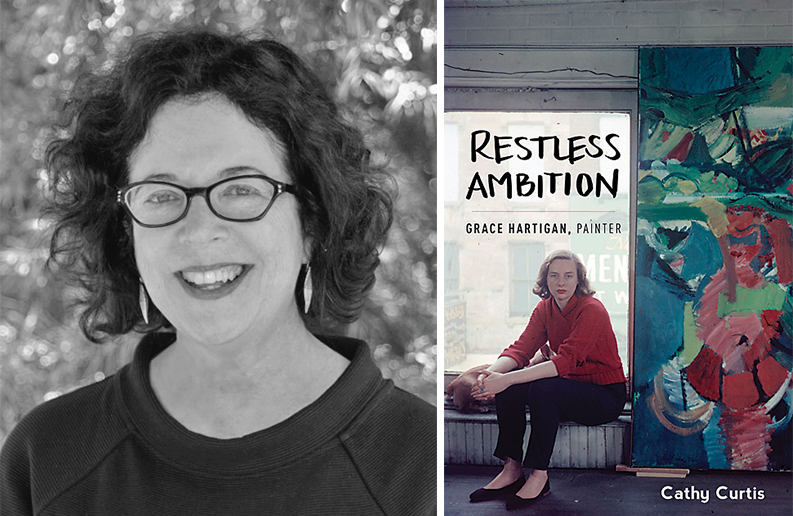

Q&A with Cathy Curtis

We talk with the author of Grace Haritgan biography Restless Ambition.

Cathy Curtis met Grace Hartigan at an exhibition in California in the 1980s. But it wasn’t until decades later that the former Los Angeles Times staff writer decided the larger-than-life painter, and beloved Maryland Institute College of Art professor who died in 2008, would make the perfect biography. We talk to Curtis about her book, Restless Ambition, and what it was like to delve into such a fascinating character.

What was it like for you when you met Grace Hartigan?

Well, the thing is I had never heard of her at the time . . . She was appearing in a group exhibition at what was then the Newport Harbor Museum of Art in Newport Beach, CA. It was the big thing happening in art, and there she was . . . There was not the sort of searching we did today, so I came clueless. She just started in on a sort of aria about her situation currently . . . I’m taking notes, lickety split. She talked about what it was like in the 1950s, how she and [fellow Abstract Expressionist artist] Bill de Kooning would be in and out of each other’s studios. Of course, with the rosiness of memory, the ’50s were then in her mind completely wonderful and the situation in 1988 was not so good. It wasn’t so good for her career anymore. She had really been eclipsed at that time.

In your research, did you find her assessment of the 1950s was correct?

In many ways it was. Yes, they were poor and they had to make do, nobody was buying their paintings . . . On the other hand, they had this incredible camaraderie in the years before people started selling . . . It was almost like a university. Many of these people had not, in fact, gone to college. They had, sort of, two institutions. One of them was what they called “The Club” where they held meetings, and they invited speakers from all sorts of walks of life. They had philosophers, authors, they had composers, and they also spent a lot of time vigorously arguing about what they were doing and why they were doing it. They also had parties, somebody would bring a record player, and there was a lot of dancing. In the early days, there wasn’t enough money to buy hard liquor so they mostly had coffee. When there was a speaker, they would all club together and get one bottle of whiskey or something, and each one would get a tiny, tiny portion in a little cup. The other side of it was the Cedar Tavern. There, too, there wasn’t a whole lot of heavy drinking in the beginning, but as artists had more money, people got pretty loaded there. Many women artists didn’t like the atmosphere there, it was very macho. But Grace, she was tall, she was statuesque, she always dressed up for the evening, she was incredibly self-possessed, and she had a really foul mouth. All of those things seem to have combined for her to be a stand out. She didn’t seem to have any problems fitting in.

Did Grace keep her ambition when she moved to Baltimore in the 1960s?

She remained ambitious always. She wanted to have a higher profile. New York was always her lodestone, New York was what really mattered. I think it was interesting to compare what she said to out-of-town newspaper writers versus what she said to the Baltimore press. I think she was rather canny there . . . She would usually think of something nice to say about Baltimore. It was interesting when she spoke to someone say in Massachusettes, she could give full vent to her feeling that one day she’d come back to New York and she’d regain her title . . . She probably enjoyed being a big fish in a small-ish pond.

Where would you rank teaching in her life, in terms of how important it was to her?

She kind of had to be talked into doing it—it wasn’t her idea . . . It was the president of MICA at the time. I think she grew to enjoy her role, because she could play her diva role with generations of students and she could re-hash her years in the ’50s. One of her students claimed [she] felt nostalgic for the ’50s herself. I guess it just became so vivid in Grace’s telling.

How did you decide to write Grace’s biography?

For years and years I wanted to write someone’s biography . . . I was in New York in the fall of 2010 and I went to this show called Abstract Expressionist New York, which was at the Museum of Modern Art, and there were all the sort of excellent, huge, and wonderful paintings. I thought this was a terrific show. Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning. And I rounded a corner and I saw a very large and absolutely drop-dead gorgeous, extremely colorful painting. I sort of leaned forward to read the name [Grace Hartigan]. And in the next month or so it just sort of clicked. I could write about Grace.

What was it like researching this book?

Grace has an archive at Syracuse University, and I made a couple of small trips there . . . She kept every single letter, it appears, from all of her students . . . there were marvelous letters from people now very well-known: fellow artists, the wife of a famous art writer. There’re all very intense, and emotional. There’s been a bad scene going on and all these letters would be fired off . . . it was just great to piece together the back and forth of it. Sometimes I didn’t even understand what the issue was . . . I never could get the actual date for when she and [her fourth husband and Baltimore resident] Winston Price had their tryst in a hotel in New York. Fortunately, Grace was writing to Beatrice Perry, her dealer in Washington, D.C., and Beatrice would say, ‘He really wants to meet you.’ You just sort of get closer and closer to when it must have been. I loved it. It was really fun.

That’s an amazing story as well, because Grace and her future husband hadn’t met each other before they had their three-day affair, right?

She was so impulsive. All her marriages were, boom, meet them, marry them. It’s almost surprising she only had four husbands, because there were a lot of lovers. I’m sure there were lovers I didn’t even realize she had there were so many of them. She had her one-night stands, and there was really a lot to keep up with . . . Finally, she meets this scientist at Johns Hopkins University, he has a media profile, he was a big shot, particularly just before he met her. And he was making good money at the university, and he was an art collector. He thought she was a sexy dame, and he really admired her painting. So she thought she had it all there.

Did your view of Grace change while you were writing the book?

I had fallen in love with Grace at that point. I thought she was just great, but I had to realize that she was a deeply flawed individual, and I just hadn’t really come to terms with it. I was just so blown away by her-larger-than-life quality . . . I still admire her, though, because she painted some marvelous paintings. It’s a strange thing that happens when you’re writing the life of someone because you feel like you’re living it along with them in some curious way.