Arts & Culture

Q&A with Gregg Wilhelm

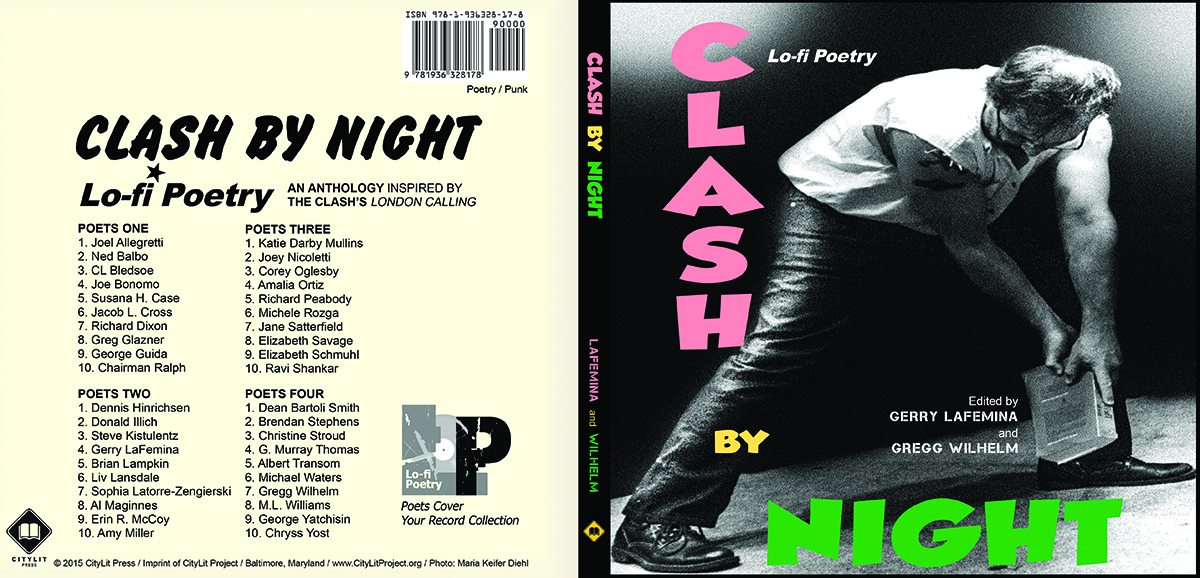

We talk to the founder of CityLit Project about a new poetry anthology based on The Clash.

Gregg Wilhelm, founder of Baltimore’s CityLit Project, and Gerry LaFemina, author and associate professor at Frostburg State College, thought they were on to something when they brainstormed an idea for a poetry anthology based on the punk band The Clash’s album London Calling. Wilhelm talks to us about the process, and why the album still resonates.

How did you come up with the idea for Clash by Night?

Gerry and I have been friends for a while . . . We met (up) in Frederick, and, as often conversations tend to go when you’re having a few beers, we thought, you know, “If you could do an anthology that covered an album, what would it be?” We were just shooting the sh*t, just riffing on ideas, and we both said this one, London Calling. So we said, “Let’s do it.” But then life gets in the way, [but] two-and-a-half years later, we finally have it. Gerry is a poet, so he put the call out, and I reached out to a few poets from Baltimore. Submissions came in in the summer 2013. We accepted maybe two-thirds of the poems that got submitted.

Why do you think it was London Calling that came to both of you at the same time?

It’s this seminal album in my teenage years. I’m a little bit younger . . . I probably discovered it in the early 1980s. Gerry also . . . he grew up in New York, was in punk rock bands in New York and still plays. For the benefit of all involved, I walked away from music at the age of 17, but I was in a punk band. Baltimore had a great hard-core punk scene back when I was a kid. A lot of my friends weren’t really into the British scene, but I was. It was just that album—everybody has that album. And part of what we want for the series is to now turn it over to other editorial pairs and ask, “What was that album for you?”

Did the poets who responded have the same kind of connection with the album?

Yeah, totally. I think that’s what makes the poetry so visceral. We have some pretty young poets in there as well, but I also think that speaks to the enduring legacy of this particular album. It’s four sides, it was a double album, which was pretty audacious for the time. It was right at a time when they were evolving. It’s very political, there’s a lot of reggae in it, they were experimenting musically, and I think it’s just so much a metaphor for what life is like when you’re [a teenager]. You’re experimenting with things, you don’t feel comfortable in your own skin, you’re trying new ideas, you’re embracing new philosophies, you’re trying to branch out. You’re rising up against the status quo, whether that is your current local or federal political situation, or your parents, your religious of philosophical ideals. I think it really resonates with everybody, and 20, 25 years later, it still resonates. You can still point back to hearing the first chords of that first track on that first side. And how the hair on the back of your neck still stands up today thinking about it.

How did you select who was going to write about each track?

That was totally organic. In fact, there were one or two tracks that didn’t have any submissions. A lot of people were writing about “London Calling” the track, or “Train in Vain.” We did then reach out to some specific people and said, “Don’t force it, but think about the track and if something authentic comes forth we’ll consider it.” It’s 174 pages, so it’s going to feel pretty substantial.

Did you give the poets any direction?

No. That’s why you’ll see prose poems, short poems, long poems. The lineation is varied, the stanza breaks are varied. I don’t recall if there was any particular form that anyone wrote in . . . no, there’s a sonnet, a Liszt sonnet. But we weren’t necessarily looking to represent each of the formal forms of poetry.

Was there anything that surprised you while working on the anthology?

It’s probably been 25 years since I had such a connection of community with this particular album . . . my musical preferences were so different from my parents and my siblings . . . growing up in the ’70s, it was all Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin. And even amongst my friends who gravitated towards the hard-core punk scene here in Baltimore, it was a different kind of punk and not the British-generated punk. So even within that subculture I was still listening to different kinds of music with the headphones on, sheltering out the outside world by myself . . . it was very much a solitary experience. So what surprised me most about working on this book is that there are so many people out there that felt similar about the album as I did and still do to this day. It’s almost a way to vicariously have that community that I didn’t have 25 years ago when I encountered the album for the first time . . . I’m grown now and quasi-mature and it sort of reaffirms that I wasn’t the sort of odd-ball kid you think you were at the moment, when you’re 15. You have some sort of affirmation all those years later that there were other odd-ball kids who were going through what you were going through, with their headphones on.

Were you expecting to feel that way? Did you have any expectations going into the project?

Not necessarily. It is a seminal album, it’s not an obscure album. Most people who were not ever into that scene know about The Clash and know about the songs. I mean, my gosh, songs like “Train in Vain” and even as late as “Rock the Casbah,” they’re the background music now. You’ve had those moments when the song that’s meant so much to you is being re-purposed to sell cars or watches, and you’re like “Oh my God, I can’t believe it.” That’s also what’s going to make this particular book of interest because it is such a recognizable, iconic piece of music. Even those who weren’t neck-deep in the mosh pit back in the day, there’s going to be a level of familiarity. And it will transcend, like all good writing should. I wasn’t there in the heyday, but it transcended to my experience in the mosh pit on Eutaw Street in the early 1980s and it will transcend to the kid in the 1990s listening to Nirvana in Seattle. We all had that moment with “the band” came along for you, right? And for our generation, because this was the first of such bands, it will resonate with people who were standing there as 15-year-olds listening to Kurt Cobain.

In terms of the future of this project, how do you foresee that happening?

We don’t have any other proposals at this point. This book has information about how to go about proposing an idea, so I think we’ll get proposals after it comes out. Gerry and I have right-of-refusal sort of power. If someone were to propose an anthology based on a Chicago album or the Moody Blues, we might be like, “Ehh.” But it could be The Beatles, which I was never really into. Well, The Beatles might be…

A little cliché?

Yeah, I think you’re right . . . If you make the case that the album was important to you and to a generation of people, I think we would seriously consider it.