Arts & Culture

Forward Facing

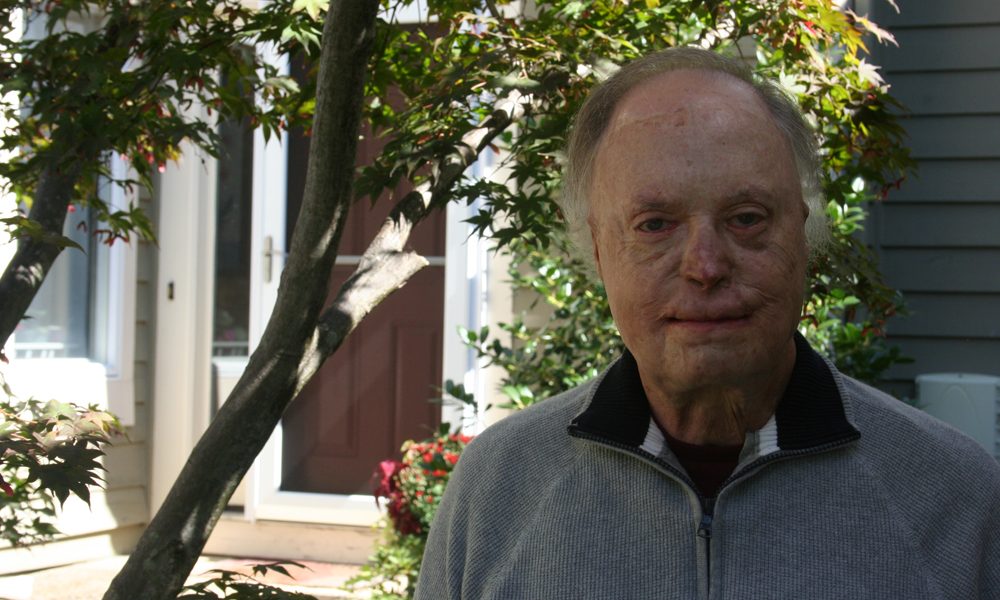

The author of Blue-Eyed Boy talks about overcoming adversity and his long stint as a Sun reporter.

Robert Timberg was less than two weeks away from shipping out of Vietnam when a vehicle he was riding in hit a land mine. The explosion left the Marine with severe burns over much of his body and disfigured his face. His memoir, Blue-Eyed Boy, recounts Timberg’s recovery from the physical wounds, as well as the trauma of losing his identity. He eventually became a journalist and covered events like the Iran-Contra scandal for The Baltimore Sun.

Your candid and unflinching appraisal of everything from draft dodging to the dissolution of your marriages is rare. What had you reaching for the delete key? What stopped you?

There’s nothing in the book that I wanted to delete that I didn’t. There were some sections I didn’t want to delete but did because friends whose judgment I trusted recommended I do so. Those sections related mostly to material that they said slowed down the story. So, reluctantly, I cut a short, comical tale of watching the porn classic Deep Throat with the now defunct Maryland Motion Picture Censor Board when I was The Evening Sun’s City Hall reporter. Some people nearly cried when I told them it was on the cutting room floor.

You did not accept the finality of a “permanent disability” and “highly repugnant” wounds. Why not?

To do so would have been to consign myself to a life of bitterness and self-pity. I hated that prospect but it wasn’t until a series of events resulted in my studying journalism at Stanford that I had a sense that life might have more than that in store for me.

And I wanted more. I wanted to matter and for my life to count for something. It was a struggle, but I found those things as a newspaperman. Yes, I was disfigured, but that had to take a back seat to getting whatever story I was chasing. And that made all the difference in the world.

There was also this. I was—and am—a Marine. I also was part of a ragtag, though damn near invincible, football team called the Lynvets that played on the sandlots of Brooklyn and Queens before I headed off to the Naval Academy in 1960. Neither organization has much use for guys who give in to misfortune. Remember that great scene in the movie Chinatown where Jack Nicholson slaps around Faye Dunaway to get her to explain her relationship to a young girl hiding upstairs?

“She’s my daughter.” WHACK! “She’s my sister.” WHACK! “My daughter.” WHACK! “My sister.” WHACK!

In my case, it was like I had both a Marine and a Lynvet taking turns whacking me around as I stood there like a sad sack.

“Say it, Bob!”

“Say what?” WHACK!

“You know.” WHACK!

“What?” WHACK!

“I don’t know what you want me to say.” WHACK!

I finally said it.

“I’m a Marine and a Lynvet!”

In what ways might journalism benefit from having more veterans in the profession?

Let me say first that my regard for the courage and professionalism of today’s war correspondents, both men and women, could not be greater. Would more veterans help? Sure. There would be fewer rhetorical lapses, like calling one soldier the “colleague” of another. And veterans would more easily see through military blather. But I felt more strongly about this issue before I observed the superb work of our current crew of correspondents in the Middle East.

From your days as a Sun reporter and/or recent experience, what’s the most under-appreciated aspect of life in Baltimore?

There is an authenticity about Baltimore that I think is under-appreciated though I think that’s changing. When you’re in Baltimore you know you can’t be anywhere else. Of course there’s the Baltimore accent. And the sports teams, now that they’re winning, contribute to the flavor of the city. So do crabs and oysters and Fells Point. Then there’s the ethnic flavor of East and West Baltimore. Maybe the most underappreciated aspect of Baltimore is recognition of how much William Donald Schaefer did to reshape the city and build its pride in itself.