Arts & Culture

From Russia, With Love: Remembering Former BSO Director Yuri Temirkanov

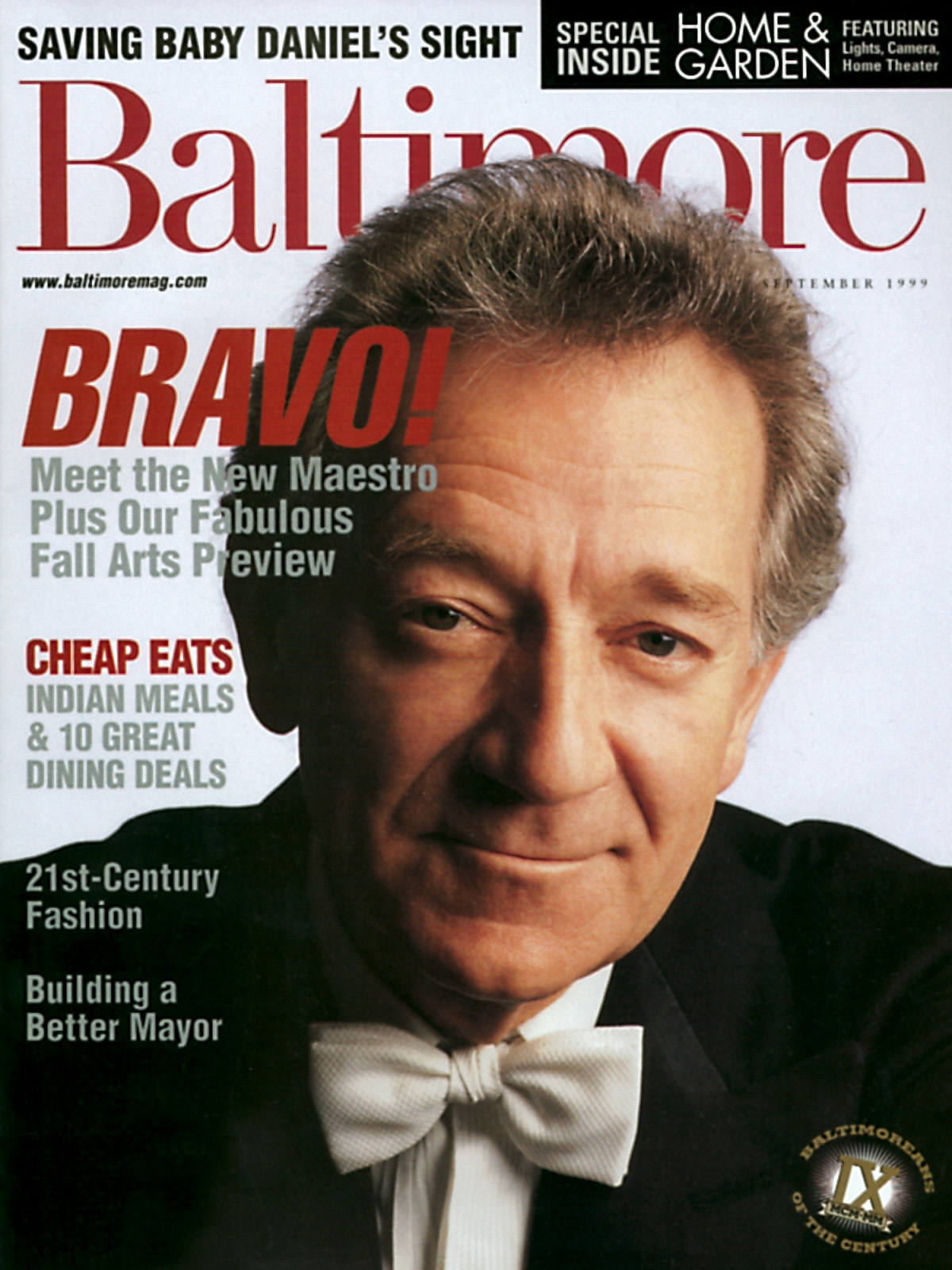

Take a look back at our September 1999 piece on the lovable maestro, who passed away this week at 84.

Yuri Temirkanov cannot tell a joke. He starts to tell it—in Russian, of course—and then halfway through, he starts to laugh. And then you start to laugh, because even though you haven’t the faintest clue what he’s saying, when Temirkanov laughs, it’s impossible not to laugh with him.

By the time he spits out the punchline, tears are streaming down his face; he’s laughing this joyous, exuberant, completely guileless guffaw. And pretty soon, tears are streaming down your face even though his interpreter—the inscrutable Mariana Stokes—has barely started translating.

At this point, the joke is completely irrelevant. But, just for the record, Temirkanov favors viola jokes. (Violas, in case you didn’t know, are the Rodney Dangerfield of the orchestra.) And here’s the first (of many) viola jokes Temirkanov tells:

How do you teach a viola player to play staccato? You write out a whole note and tell him it’s a solo.

(Okay, so maybe it’s funnier in Russian.)

When David Zinman announced his retirement as music director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra two years ago, you could feel the panic in the music community. It was Zinman who had put the BSO on the map—made it artistically viable, world-renowned, even cutting edge. And it was Zinman who had really connected to Baltimore audiences with his regular-guy, artist-as-mensch persona. How could we possible replace him?

Enter Yuri Temirkanov.

It’s not just that the 59-year-old Temirkanov—the music director of the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra and the former principal conductor of the Royal Philharmonic in London—is widely considered one of the most prodigiously talented conductors alive. It’s also that Temirkanov is so completely lovable.

There are some people who exude empathy, whose every facial expression, gesture, vocal inflection conveys an emotion. That’s Temirkanov. You can see this remarkable body language when he conducts. As he dances on the podium, waving his arms (he doesn’t use a baton), he looks like he’s playing an elaborate game of charades. Here he’s petting a horse. Here he’s churning butter. Here he’s tinkling at an imaginary piano in the air. And yet every gesture is eminently clear.

The horse petting thing: That’s Temirkanov trying to get the brass to play with a more emphatic rhythm. The butter churning, that’s urging for a more blended, sweeping sound. The tinkling in the air, that’s to suggest the tossed-off nature of a woodwind arpeggio.

“He’s very clear with what he wants,” says Phillip Kolker, the orchestra’s principle bassoonist. “He doesn’t speak much, but he has a very effective way of communicating.”

Because of his emotional expressiveness—coupled with his puckish good looks (he suggests a smaller, older Kenneth Branaugh), his romantic sensibilities (he has a penchant for lush interpretations of Beethoven and Shostakovich), and his insouciant charm (at a spring press conference, reporters hung delightedly on his every word)—Temirkanov is already a big hit with Baltimore fans.

When he performed his first concert series as BSO music director last March, the crowds were simply ecstatic. It was as if the audience wanted to embrace Temirkanov with a giant bear hug of applause and appreciation.

Temirkanov is humbled by this warm response—”it’s incredibly touching,” he says—but it’s a safe bet that he wasn’t happy with any of his first three performances.

“I never had a concert where I said to myself, ‘Ahhh, that was really something!'” he explains, munching on a cannoli at Vaccaro’s Italian pastry cafe in Little Italy. “When I play the concert, I know exactly what has gone wrong. And when people say, `Wonderful! Wonderful!’ I listen to the compliments with pleasure. But I know it wasn’t that good.”

He equates the praise of concertgoers with well-wishers at a funeral. Then he giggles at the thought: “Have you ever heard a bad word at a funeral? If only the people could hear what is said about them! No one felt this so strongly when they were alive!”

To Temirkanov, a true artist is never satisfied with his work. “It will mean that I’m beginning to die as an artist,” he says.

Striving to be a great artist is the focal point of Temirkanov’s life. Sure, he has hobbies—fishing, cartoon-drawing (he can whip off a giant-schnozzed, Hirschfield-like caricature of himself in 30 seconds flat). And of course he has family: His son plays violin with the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, and his beloved wife died in 1997. But it’s clear that music shuts out most other earthly concerns. As such, he is notorious for eschewing such modern trappings as computers and televisions and cars.

Once, ill-advisedly, the trusty Marina Stokes—who has been with the maestro as an assistant and friend for over 15 years—tried to teach Temirkanov to drive.

“It was a disaster,” she says with thinly concealed mirth. “He drove over a flower bed.”

“You see!” laughs Temirkanov. “Even my left foot is romantic! I don’t drive into cars. I drive into flower beds.”