Arts & Culture

The Marble Bar, a Haven for Punks and Misfits, Closed Its Doors for Good 35 Years Ago

Though shuttered for more than three decades, the Marble’s legacy lives on in the dizzying array of talent it fostered.

Talk to any Baltimorean who was a punk in the late ’70s and ’80s, and they will wax rhapsodic about the Marble Bar. It was the coolest place, with the coolest bands, and the coolest vibe—like nothing that came before it or since. Either you were lucky enough to have been there in person, or you missed out—your loss.

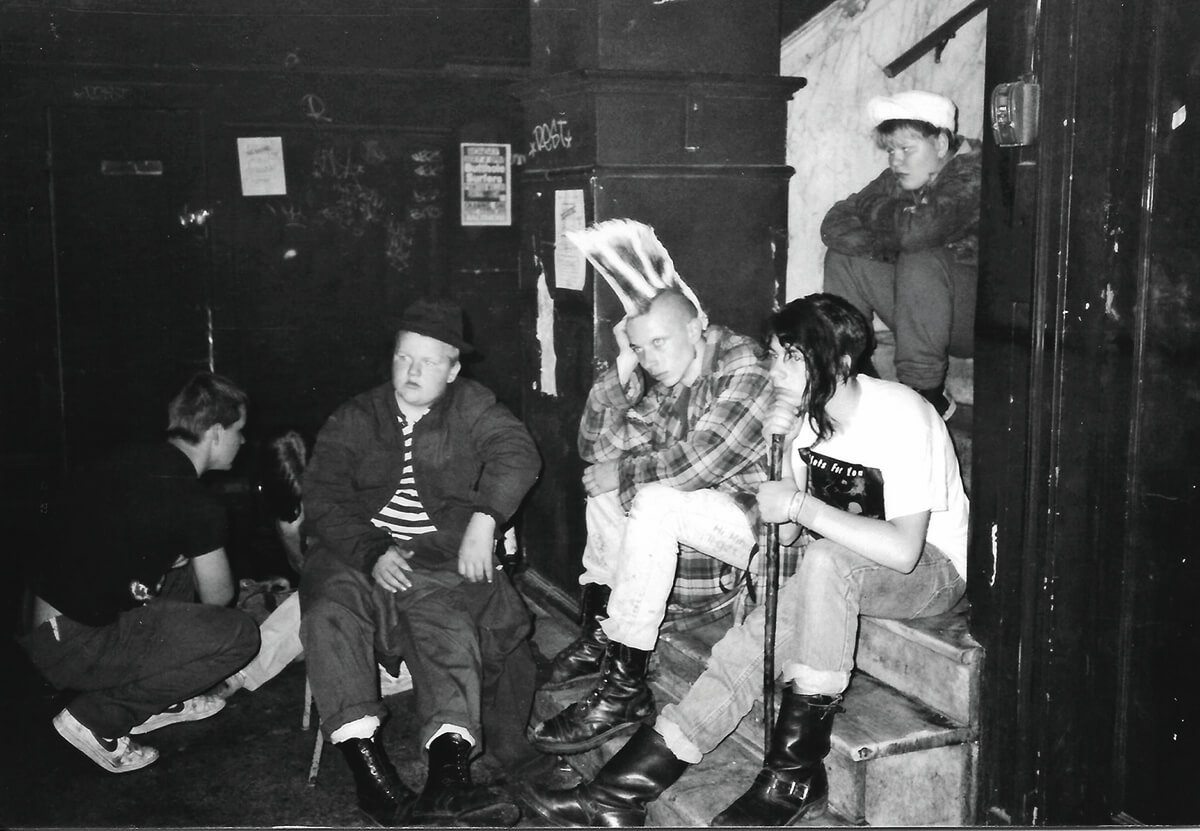

“It was a refuge for a lot of people, and nobody judged you,” explains David Wilcox, a musician and artist who created many of the bar’s iconic flyers with his brother, George. “You knew you were hiding in a safe place to be who you were. If you had a two-foot-high mohawk, nobody was going to bother you [there], but you walked out onto Eutaw or Howard Street and somebody might hit you in the head with a rock.”

You must remember, in the 1970s, disco was king. Top-40 cover bands and DJs kept bars full and crowds dancing. As a result, alternative bands, especially punk and New Wave acts like The Slickee Boys, Thee Katatonix, Root Boy Slim, Suicide Commandos—and even Talking Heads—struggled to find a place to play. But one Baltimore club in the basement of the historic Congress Hotel at 306 W. Franklin Street emerged to fill the void. And that was the Marble Bar.

Talking Heads co-founder and frontman, David Byrne, who grew up in Baltimore, recalls, “At that time, the network of clubs where emerging acts could play was spotty and limited. We played Marble Bar when Talking Heads just had our first record out, which allowed us to play outside the handful of NYC clubs that had supported us. We’d mostly travel by station wagon…eventually maybe there was a van. It was very DIY.”

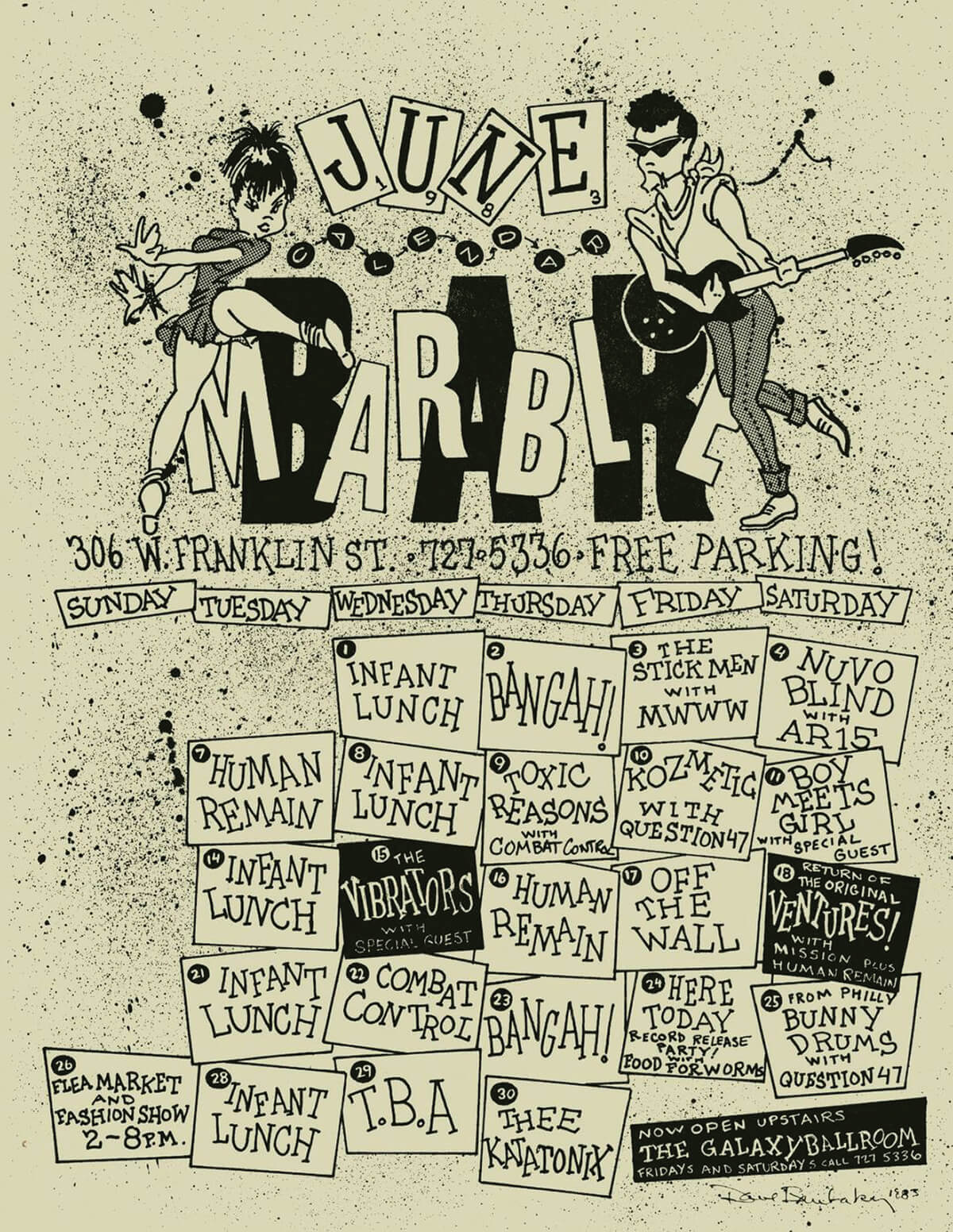

Byrne’s experience was typical of the time. For Baltimore indie musicians, nearly everything about the music scene was DIY. Bands communicated through handmade flyers, zines, and calendars often created by students at the nearby Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). The September 1980 Marble Bar flyer announced: “Legendary Chick’s Nite every Thursday! THE BEST RECORDED MUSIC OF ALL TIME!! All girls free!! 75 cent beer. All guys $1.00. Bar drinks $1.00.”

“The Marble Bar was really Baltimore’s CBGB’s,” explains Harry “Chick” Veditz, who ran Chick’s Legendary Records on Sulgrave Avenue and spun records during that Thursday night gig.

DJ Rod Misey, who hosted the New Wave/Pandora’s Box show on WCVT says, “For a lot of us, this was a place where we kind of grew up.” The Go-Go’s drummer and Dundalk native Gina Schock played the Marble with her earlier band, Scratch N’ Sniff, and has fond memories of the grubby space. “It was like the hippest, coolest place. If you were a musician, that’s where you wanted to go.”

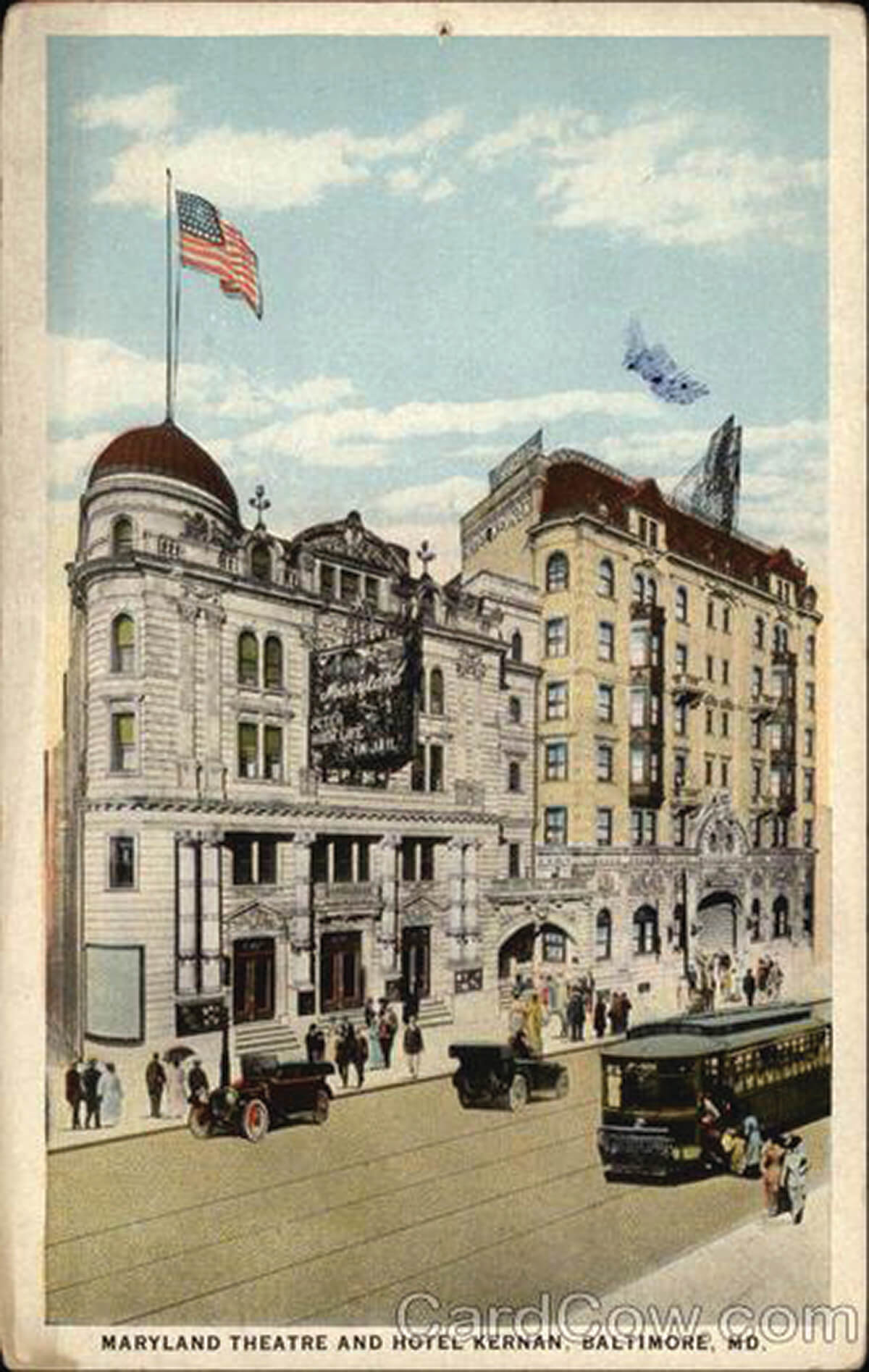

Originally named the Hotel Kernan after its builder, theater magnate James Lawrence Kernan, The Congress Hotel was built in 1903 to cater to lovers of musical theater. The six-story French Renaissance Revival-style hotel boasted 150 sumptuously appointed guest rooms and an art gallery. Two underground tunnels housed a Turkish bath, a barbershop, and a swimming pool, and connected hotel guests to the adjacent Auditorium (today the Mayfair Theatre) and Maryland Theatre (demolished in 1951), both owned by Kernan. A savvy promoter on par with P.T. Barnum, Kernan billed his hotel and theatrical complex as a “Million-Dollar Triple Enterprise.”

Kernan’s Million-Dollar Triple Enterprise transformed Franklin and Howard Streets into the nexus of Baltimore nightlife. The Maryland Theatre headlined the top vaudeville talent of the day, including Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, and later Will Rogers, Weber & Fields, Al Jolson, and Eddie Cantor, while the Auditorium focused on traditional plays.

Capitalizing on the steady influx of German immigrants to the U.S., Kernan outfitted the hotel’s basement as a rathskeller—a traditional German beer hall. Dubbed “the bear pit” after the mascot of Berlin depicted on the German capital city’s coat of arms, it was the city’s first true nightclub. The Great Depression saw the decline of the era of the grand downtown hotel. In 1932, the Penn Mutual Life Insurance Company bought Kernan’s Million-Dollar Triple Enterprise at a bankruptcy auction for a paltry $225,000 and reopened it a year later, on October 5, 1933, as The Congress Hotel.

By the seventies, The Congress had slid into flophouse status, its single-occupancy rooms renting for less than $5 a day. In 1977, brothers Angelo and Samuel (“Sam”) Palumbo, an engineering draftsman with the city’s housing department, purchased the property. In 1979, the brothers racked up a staggering 174 housing code violations, including citations for a lack of working smoke detectors. A contemporaneous article in The Baltimore News-American lamented that “The Congress became shabbier and shabbier, like an old movie star down on his luck.”

“Pretty much a fleabag hotel,” is how jazzman Scott Cunningham recalls The Congress. In 1976, when Cunningham was searching for a venue for his eponymous jazz band, not only the hotel but also its surroundings had gone to seed. Sam Palumbo showed Cunningham the lobby-level Galaxy Ballroom and then the dust-encrusted bar in the basement. Peering through the patina of grime, Cunningham spotted potential in the subterranean space. He wasn’t wrong. Once they took down the vinyl panels covering the wall behind the bar, it revealed the original oak paneling and mirrors from the space’s rathskeller days. But the biggest payoff proved to be the bar itself. Scrubbing away decades of rust-colored soot, Cunningham and his helpers unveiled the crowning glory: a spectacular, 72-foot-long bar hewn from white Italian marble. Cunningham had found his venue—and a name: the Marble Bar.

To build word-of-mouth buzz and a following, Cunningham handed out flyers at the nearby University of Maryland School of Medicine and offered free admission to students. The Scott Cunningham Band played there several nights a week while Cunningham worked with a promoter to book an eclectic mix of acts, including Muddy Waters and Talking Heads.

The Marble’s loyal following would be cemented by Cunningham’s successors, Roger and LesLee Anderson. In 1974, Roger, a bluegrass and rock ’n’ roll player from Kentucky who grew up on Baltimore’s westside, also was looking for a venue for his band, Clear. An engineer by day, he’d met Sam Palumbo on a project for the city. The two men hit it off, and Palumbo offered him the Galaxy Ballroom. For three years, Roger’s band performed in the hotel’s lobby-level ballroom.

Meanwhile, down in the basement, the Marble was struggling. The spartan space lacked heat in the winter and AC in the summer. Construction on Franklin Street cost the bar its precious parking lot. Cunningham closed it in 1978, and Sam Palumbo handed the Andersons the keys, asking them to manage and rent the space.

At the time, the Andersons were packed for a move to California they never made. Before sealing the deal, the couple met with Palumbo, who, according to LesLee, treated her as if she was invisible. Furious, she returned home and laid down the law. “Before I go down there and work, he’s gonna respect me. And that’s all there is to it,” she remembers saying. Thereafter, she managed both Palumbo brothers with a mixture of modern feminism and old-school charm.

Soothing the brothers’ periodic outbursts proved the least of the Andersons’ challenges. The crowd-pleasing disco bands were pricey, some having as many as nine musicians, a serious consideration given that the couple had to pay the talent out-of-pocket. On top of the cost, Roger despised disco. The alternative: Bring in a new, fresh sound that wouldn’t cost a lot. “And in walks the punks,” remembers LesLee with a laugh.

Though Roger was initially against booking punk acts—he famously turned down The Police—he was eventually won over. Da Moronics and Judies Fixation were the first punk bands booked. Off the Wall and The Slickee Boys played the Marble once a month, drawing crowds that, according to LesLee, “kept us afloat.”

LesLee remembers Roger saying, “‘These kids, they’re playing three-chord music. And they’re having the time of their life. I’ll book more of them…as long as they act right.’”

To many people’s surprise, the kids did act right. Roger made sure of that.

“Nobody messed with Roger,” says Wilcox, the lead singer of the band Rock Hard Peter. “I remember him breaking up an entire cluster, whether they were moshing too crazily or whatever, with a two-by-four. Things pretty much calmed down after that. He ruled with an iron hand and a heart of gold.”

“ROGER AND LESLEE GAVE BIRTH TO A SCENE THAT ALLOWED PEOPLE TO BE FREE AND EXPRESS THEMSELVES.”

Roger took a personal interest in the young artists who flocked to the bar, buying instruments for budding musicians who couldn’t afford their own, and even allowing graffiti in the hotel’s former barbershop, then used as the bar’s main entrance. Says LesLee, “Roger always said, you give kids art and music at a young age, and it’ll save their life.”

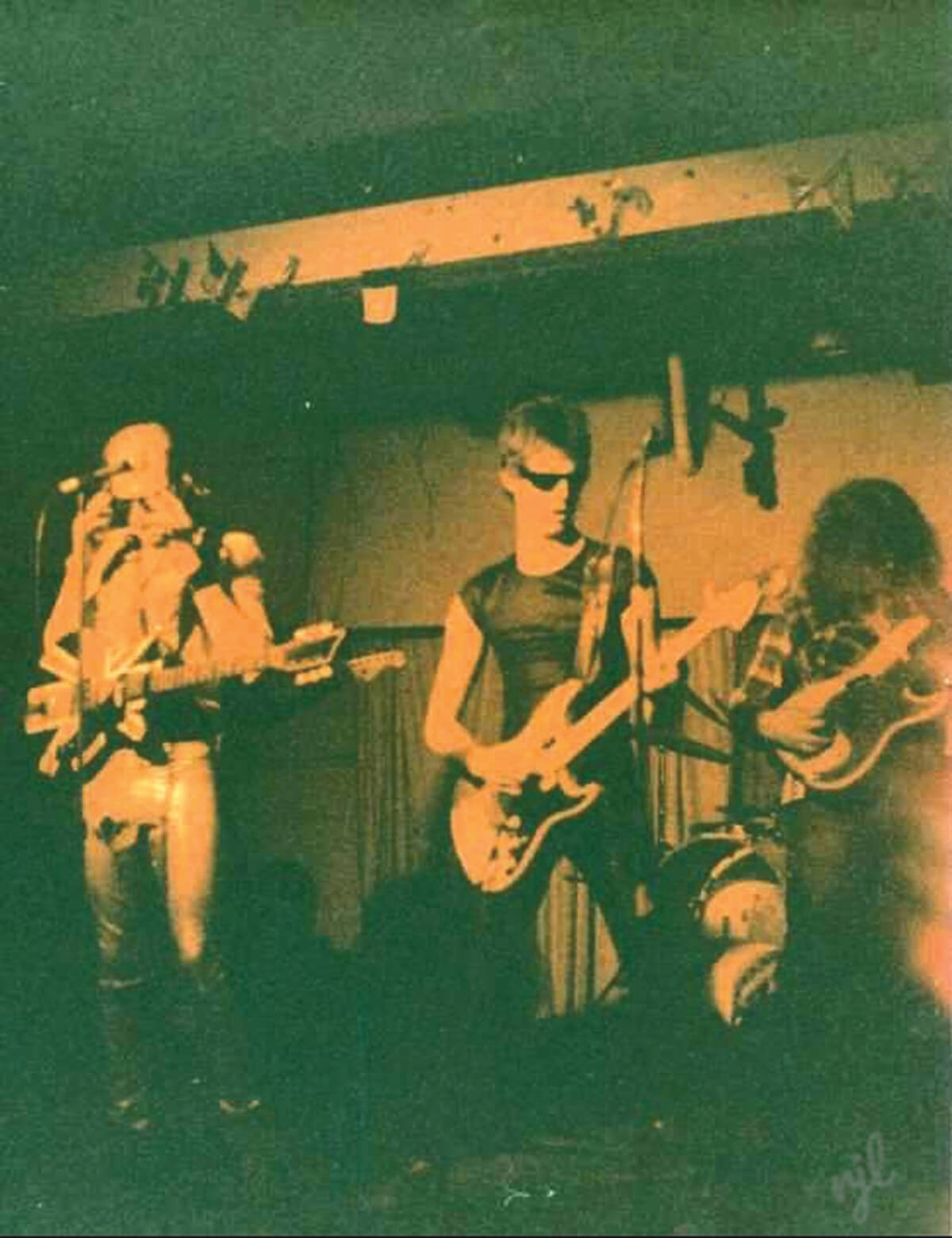

Under the Andersons, the Marble Bar became the place to hear punk music. Steep steps led club kids from the street into a blanket of blackness, the only lighting coming from the stage and behind the bar. The cavernous atmosphere fostered a sense of autonomy. And freedom. Flooding the dance floor were patrons sporting styles from mohawks to dreadlocks, many of them dancing with themselves. It was a dungeon to some, a sanctuary to others.

LesLee has fond memories of how Roger used comedy to clear out the bar at closing. “He would say things like, ‘This is not your mother’s womb, so don’t get too comfortable.’ Or what would really make, ’em run out the door—‘All virgins can stay.’”

Last call at the Marble may have been at 2 a.m., but for the Andersons, operating the club was a 24/7 labor of love that expanded to hosting fashion shows, art exhibits, poetry readings, and even rock ’n’ roll flea markets.

“We didn’t have any kids,” LesLee explains. “We weren’t very extravagant people. We just put everything right back into the bar—bigger shows, more music, national acts.”

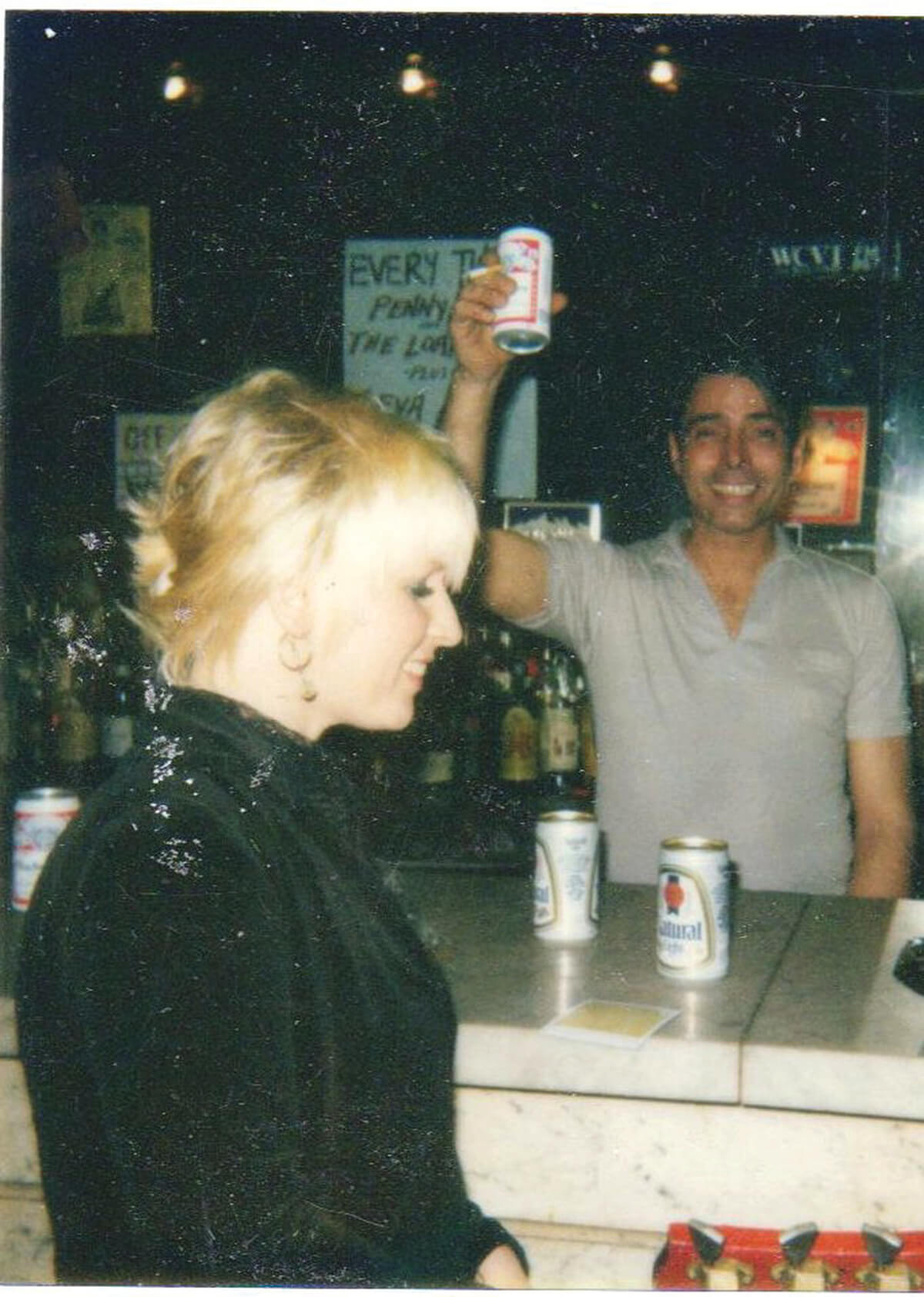

LesLee, herself a musician and songwriter, had barkeeping in her blood. Her family owned Nelson’s, a local watering hole in Southwest Baltimore. At the Marble, she wore many hats, including managing and tending bar, booking the acts, and acting as a surrogate parent for many of the young punks. “They called me mom, all the little punk girls there with their little black lipstick and their black rouge. They’d all call me mom, a whole pocket of them. They still call me mom.”

Tommy DiVenti, co-founder and guitar player of Da Moronics, remembers, “Roger gave birth to a scene there, along with LesLee, that allowed people to be free and express themselves in a manner that you couldn’t find anywhere in any other venue or club or scene. It was the scene.”

Craig Stinchcomb, a ninth-generation Anne Arundel County resident, played the Marble 69 times with his band, Judies Fixation. “It was really hard to have a bar give you a shot. And that’s where the Marble Bar came in. All of a sudden, you had two, three, four different bands a night. That hadn’t existed before.”

It was hectic. At the pinnacle of the Marble’s popularity, the Andersons were booking multiple bands seven nights a week. One of Wilcox’s favorite Marble memories was when the New Jersey-based Misfits played.

“The bass player and frontman, Jerry Only, had just bought a brand-new bass. The Misfits were all back in the dressing room, and Jerry said, ‘Where can I get some spray paint?’ There was a Read’s Drug Store right on the corner, so Jerry sent somebody down there and he came back with three cans of black spray paint. Jerry didn’t cover the pick-ups or strings. He just sprayed the whole guitar flat black and went on stage and played it that way. And I was just like, ‘Well, this definitely says something about punk rock.’”

Robin Linton, LesLee’s right hand behind the bar, loved that the Marble brought together patrons from all over Baltimore at a time when most stuck to their local corner bars. At the Marble, “You would have drummers from Glen Burnie or a bass player from Towson and the guitar player from Dundalk, and the frontman might be from Perry Hall. It was amazing that one bar brought the whole town and the whole of Central Maryland together.”

For six years, it was a whirlwind ride. Until April 26, 1984, when the party ground to a halt. While mopping the stage, with LesLee nearby, Roger dropped dead from a heart attack. He was just 37. It happened so fast that at first LesLee told herself he must be pulling her leg. Numb but determined to press on, she kept the bar running for another year, most of which she spent camped out on a cot in the basement.

LesLee was sleeping soundly one night in December 1984 when, in the wee hours, thieves broke in and stole her money, her guitar, and her wedding ring. The Central District police officer who arrived on the scene had been friendly with Roger and respected the tight ship the couple ran at the Marble. By then it was well-known LesLee was running the bar solo, and he urged her to close up shop for her safety.

LesLee chose Memorial Day weekend 1985 for the bar’s finale, the date coinciding with punk icon Edith Massey’s birthday, which the Marble hosted every year. The final hand-written schedule, a dizzying two pages long, listed every band, more than 240, that had ever performed there. Fittingly, the Memorial Day lineup included LesLee’s band, the Twisters, and Roger’s former band, Clear.

“It was like an era had ended,” LesLee says. “A family home, a musical home, was just boarded up and it was very, very hard on a lot of people.”

Afterward, Linton and her husband, Edward, sound man for Thee Katatonix, along with the late Joe Gary, took over the club for a year, booking local bands for all-ages shows, which eliminated the hassle of a liquor license. Periodically, others tried to step in and restart the party, but the moment had passed. On May 9, 1987, the Marble closed for good with a final show featuring Thee Katatonix, Da Moronics, and Human Remain.

In 2000, the hotel was redeveloped as mid-priced apartments, but the former Marble still awaits its next act. A plan by the current building owner, Zahlco Development, and Sarah Sullivan and Michael Seguin of Mobtown Ballroom to reopen the space as a coffee-to-cocktails cafe was scuttled by the ongoing COVID pandemic.

Though shuttered for 35 years, the Marble’s legacy lives on in the dizzying array of talent it fostered. A Flock of Seagulls, Huey Lewis and the News, The Psychedelic Furs, Iggy Pop, Black Flag, Dead Kennedys, X, and Bauhaus are just a few of the bands who played the Marble on their rise to fame.

“Venues like Marble Bar were and are critical as a first step for many artists,” says Byrne. “It’s a whole ecosystem, and without an initial step like the Marble Bar, a lot of emerging acts have no options…and music fans who are adventurous and curious won’t have options either.”

DiVenti adds, “I don’t think Roger and LesLee even realized how big and how much of an influence they had because you just don’t realize it’s over until it’s gone.”

Today the torch is tended by the same punk kids, now in their 50s, 60s, and 70s, who once slam danced on the Marble’s beer-soaked floor. In 2009, a private Facebook group, The Marble Bar (Baltimore), was created. Today, more than 1,300 members post anecdotes, photos, artwork, and other memorabilia.

Member Tommy Reed, the bass player for the Marble Bar’s house band, The Alcoholics, shared the following sentiment on the group’s page: “This was our watering hole, our dungeon, our refuge from the norm. We came together under this banner, under this dilapidated hotel, in this beautiful black basement that smelled of sweat and beer and a thousand nights of disparate rebellion…For it was there that we found ourselves…”