Arts & Culture

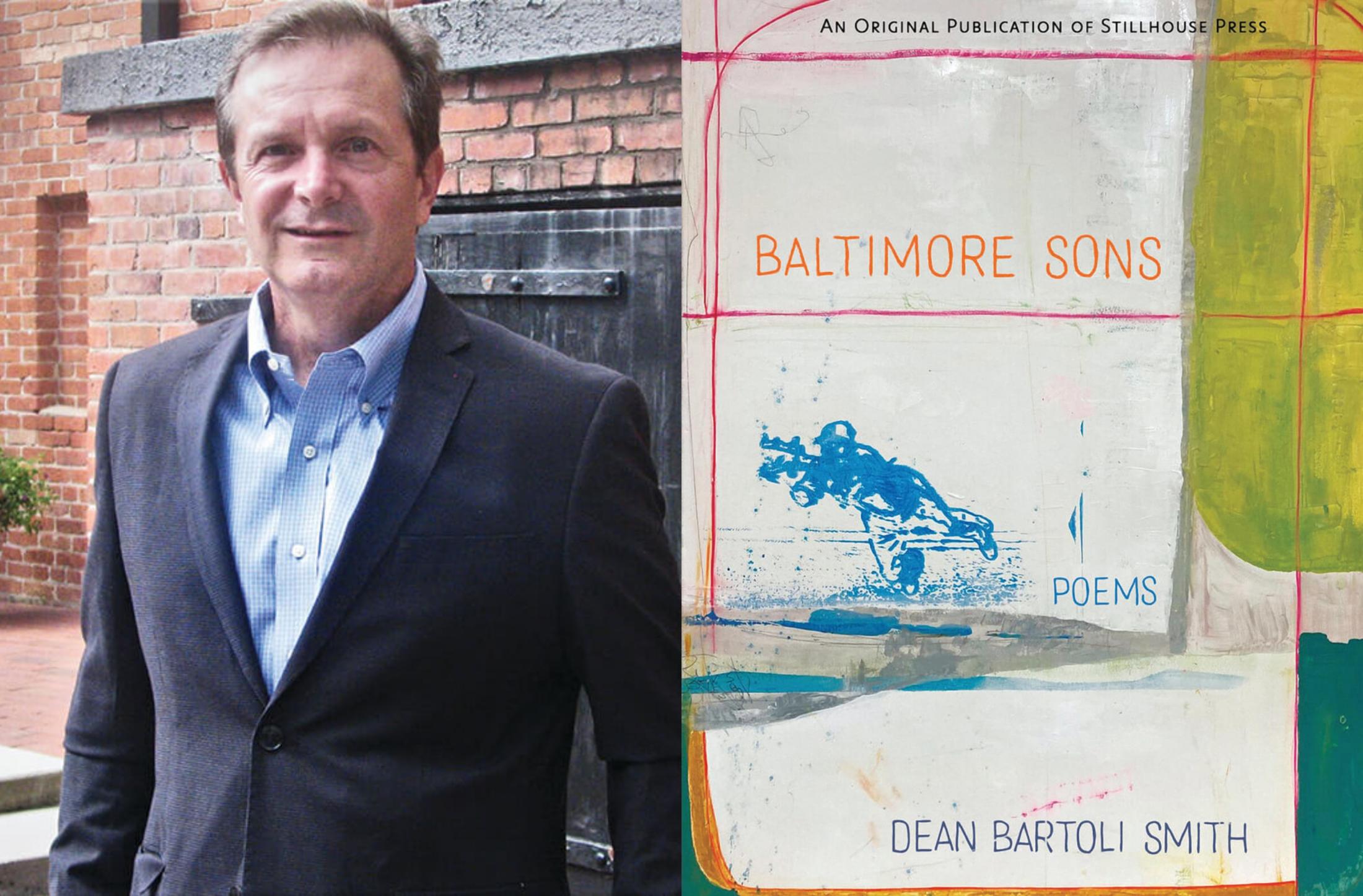

Dean Bartoli Smith’s ‘Baltimore Sons’ Captures City’s Struggles, As Well As His Own

Smith discusses the new collection, which ultimately forms a broad story of acceptance and empathy.

Dean Bartoli Smith is a Baltimore native, coming of age just in time to watch the Colts and Orioles in all their late ’60s glory. And, just in time to witness Baltimore’s long economic decline and the subsequent fraying of the city’s fabric.

A published author, freelance journalist, and poet, Smith’s first book of poems, American Boy, won the 2000 Washington Writer’s Prize and was awarded the Maryland Prize for Literature in 2001. Locally, his fiction has appeared in The Loch Raven Review and Little Patuxent Review. His prose has appeared in the Best American Poetry blog, Zocalo Public Square, The Catholic Review, Indiewire, and the Woodstock Independent, among other publications.

Currently the director of Duke University Press, Smith’s new collection of poems, Baltimore Sons, captures the city’s struggles as well as his own, as both his family and Baltimore seem to be decaying separately and together across the past half-century-plus—ultimately forming a broader story of acceptance and empathy.

One of my favorite small poems in the collection is the four-line piece, Cardboard Note. It’s such a simple, clear-eyed noticing of one of life’s poignant details—“due to the passing of Miss Annie Mae.” It seems like a lot of your poems are made of such tactile observations.

That poem remained tacked on my forehead for 30 years until I sent it to the journal Poetry East in 2019. The Polk Street Diner [where the note was taped] was a smaller version of The Wyman Park Restaurant and I lingered in the doorway. So much depended on Miss Annie Mae. What happened to her? That’s where the reader comes in and gets to finish the story.

Speaking of diners, At the Bel-Loc Diner is so bittersweet. We see your father reliving his divorce—specifically the painful separation from his two boys—through your divorce. Did the power of the moment register at the time?

Everything still registers. I could somehow see behind his shades tears welling in the sunlight that morning. We have very few extended and unfettered one-on-one moments in this world. It stayed with me and it took years to get right.

These poems span a Baltimore lifetime, from childhood memories to fatherhood to the death of your mother. How long was this collection in the making?

Thank you for mentioning my mother. I describe her as “murderous and beautiful.” That says something about the process and my own sense of what I was going with the collection. It took me more than 20 years to finish it.

Can we ask you about a favorite poet or influence? Someone whose craft you appreciate?

Robert Lowell’s Life Studies opened the door. Sylvia Plath was inside the room. The voice and craft of Gwendolyn Brooks, who I met at UVA as an undergrad. Paul Muldoon’s poem, “Meeting the British.” Mark Strand told me the best poems cultivate a shared sense of suffering. David Lehman got me back to the desk.

Many of the poems deal with drinking, drugs, and guns, sometimes personally, sometimes in Baltimore, and in America more broadly. It doesn’t seem like the city or country has become any easier to live in. At times, in pieces like “Father’s Day Shotgun Sale,” the poetry seems almost surreal.

It can be a brutal read, but there is hope. There is empathy. Isolation is the real killer. I went for a walk in the city recently on a beautiful day. I had so many things to do and felt guilty at first. I saw something akin to “Cardboard Note” that could form the basis of a new collection of poems—a response to Ezra Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro.” I’ve waited my entire life for that.

The great Pittsburgh poet Jack Gilbert has a line in The Great Fires about deep-rooted memories—“What lasted is what the soul ate.” For him, in middle age, what has lasted is unexpected. Do you agree?

What has lasted is far beyond my wildest dreams. My life for one thing. The urge to write the next poem.