Ava DuVernay’s

Selma begins where a lesser film might end. Martin Luther King Jr. (David Oyelowo) is in a hotel room with his wife, Coretta Scott King (Carmen Ejogo), readying himself to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. It’s 1965 and he is already famous, already being granted one-on-one audiences with President Lyndon B. Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) in the oval office, already, well, MLK. So he worries. He worries that his tuxedo, with its grand cravat, makes him looks too full of himself. He worries that if he continues to consort with diplomats and presidents, he’ll alienate the very people he needs to lead. He worries about all this because he still has work to do.

Like Steven Spielberg’s

Lincoln, Selma lifts the curtain on a great man who has already achieved greatness. Having helped pass the Civil Rights Act, King is now focusing his attention on voting rights. Technically, blacks are allowed to vote all over the country, but that right is not being enforced, particularly in the south. Early in the film, we meet proud Alabama resident Annie Lee Cooper (Oprah Winfrey, whose ability to disappear into a character never ceases to amaze me) as she’s trying to register to vote. The registrar keeps attempting to trip Cooper up, first by asking her to recite the preamble of the constitution (she calmly nails it), then by grilling her on increasingly arcane civic trivia, until she stumbles. He sends her away for being an insufficiently informed citizen.

Knowing about this kind of treatment—and much, much worse—King appeals to Johnson to write a new law enforcing voting rights, but the president balks. “You’re an activist. I’m a politician,” he explains to King— and as such they have conflicting agendas.

(A note on the controversy surrounding the depiction of Johnson in this film: He’s shown as a political pragmatist, and as smart—and stubborn—as King. It’s also made quite clear that he does believe in civil rights—he just doesn’t want to be bullied into enforcing them on an accelerated timeline. The only truly inflammatory thing in the film is the suggestion that LBJ tacitly endorsed J Edgar Hoover’s nefarious tactics, which included spying on King and sending an incriminating tape to Coretta implying that King was having an affair. (He was, in fact, having affairs, but the tape was doctored.) In my mind, the depiction of LBJ here—as a savvy populist with reformist tendencies—tracks very closely with the LBJ depicted in the stirring documentary

Freedom Summer, which covers the events leading up to Selma.)

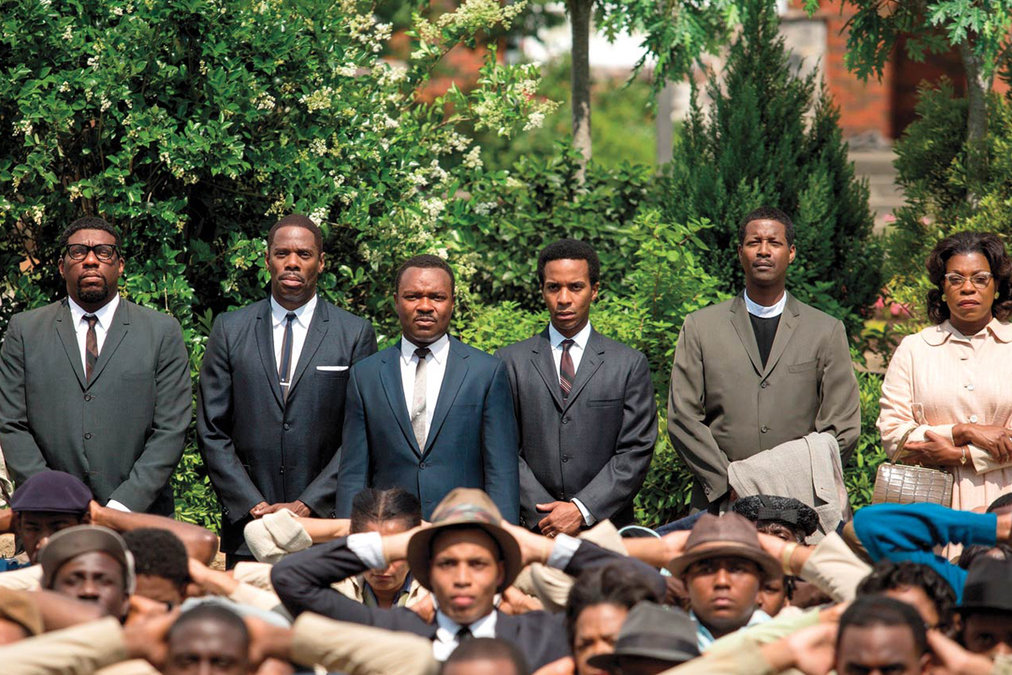

Without the help of the White House, King realizes that he has to go it on his own, so he assembles his team—including Diane Nash (Tessa Thompson), Reverend Hosea Williams (

The Wire‘s Wendell Pierce), and James Orange (Omar J. Dorsey)—and heads to Selma, AL, a town they’ve deemed “perfect.” Why is it perfect? Because all of the lawmakers—and law enforcers—are white, and mostly racist, all the way up to the state’s governor George Wallace (Tim Roth). King’s plan is to hold rallies for voting rights in highly public places and make sure the media sees the inhumane treatment of his people at the hands of the police. In a sense, then, there are casualties of King’s nonviolent war. A few people have to get hurt, clubbed, unfairly arrested, to move the needle on public sentiment. (This is one of the reasons why I’m baffled that LBJ defenders feel the film only depicts their guy unfairly. It also has an extremely clear-eyed view of King. He’s the film’s hero, for sure, but not a saint. He, too, is shown making tough decisions and compromises.)

In some ways,

Selma is a civic-minded film—it is interested in behind-the-scenes machinations, the process behind King’s protests. It also doesn’t shy away from shocking violence—one in particular, early in the film, will shake you to your core. Other times, DuVernay slows down the camera so we can see the terrified faces of people being clubbed or trampled by police. The effect is extremely upsetting, as it should be. It’s also bitterly ironic that some of these scenes—especially those where peaceful protesters face off against hostile police—evoke protests in Ferguson and elsewhere. They make it nearly impossible to tidily put the events of Selma in the past. The film feels urgent.

But

Selma perhaps works best in its more emotional moments. In one, King comforts Cager Lee (wonderful Henry G. Sanders), whose grandson has just been shot in cold blood by the police. Standing with the young man’s sheet-covered body on a gurney behind them, they share a moment of quiet reflection and grief. And yet, in the midst of this impossible sadness, both men have faith and even hope.

King was a pillar of strength in that scene, but again and again, we see him falter, as the burden of leadership becomes almost too much to bear. King has moments of doubt, moments where his conscience weighs on him, and moments where he wants to give up. In one such scene, a young John Lewis (Stephan James), who idolizes King, reminds his mentor of his own words, and that’s just enough to rouse him.

DuVernay gives us a complete picture of a movement and a man, and she is aided greatly by Oyelowo’s terrific performance. The British (!) actor sounds just like King—he has that same incredible instrument, both booming and mellifluous—and with the right hairline and signature mustache, he looks enough like him to convince. More importantly, he gets to the heart of this late-era King, a man who is not a wide-eyed optimist, but a brilliant and determined leader, who turned dignity into an art form, who fought through doubt and anger, and whose composure and vision sustained a movement.