Arts & Culture

‘SNL’ Actress Ego Nwodim Brings Improv to Baltimore Schoolchildren

The Baltimore County native aims to help local youth explore and embrace the possibilities. The “yes and” of life.

Saturday Night Live‘s Ego Nwodim talks about improv likes it’s her therapy—or maybe even a form of religion. When she was a student at Eastern Tech High School in Essex, she knew she wanted to act, although her Nigerian-American parents wanted her to be pre-med.

She compromised—leaving Baltimore to study biology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, the center of the entertainment industry. It was in L.A. where she discovered improv.

“I didn’t even know it existed,” she says from her home in New York City. She immediately fell for the art form that famously encourages “yes and”—an openness to possibility, a generosity in the way you interact with other people, a tool for being present and in the moment.

But it wasn’t just the practice of improv that energized her, it was discovering that such an art form even existed.

“I feel like, as a child, I was aware of very few professional paths available to me,” she says. “So to me, improv represents expanding your horizons. The knowledge that there was this art form out there that’s available to anyone was very empowering.”

After college, she took classes at the Los Angeles chapter of the famous improv troupe, the Upright Citizens Brigade, and did a one woman show, Great Black Women…And Then There’s Me.

She was good at it. So good, in fact, that Lorne Michaels and Saturday Night Live came a-callin’.

With her adorably scratchy voice, big smile, and gleefully silly impressions, Nwodim became an instant fan favorite. She’s been on the show since 2018 and has also appeared in multiple TV shows, films, and commercials. She’s very much a rising star.

As a sketch comedy show, SNL allows Nwodim to flex some of her improv muscles. But it isn’t actual improv, which uses no script. And she misses it.

“I’m not in the practice of doing improv regularly. When I [was doing it,] I think I was a better person, a better version of myself,” she says. (See? Therapy.)

She notes that it has become an even more crucial life skill at a time when we spend so much of our lives with our noses buried in our phones. It helps to foster better communication, better understanding, and, of course, better listening skills.

In fact, Nwodim is such an improv true believer, she recommends it to friends who aren’t even in showbiz. “I have a friend who is an accountant and I encouraged her to take an improv class!” she says with a laugh.

At some point, she realized that she wanted to bring this art form that she loves to kids, not just to share the life skills that come with improv, but to open their minds to life’s possibilities—that idea that if you see it, you can be it.

“I had people I looked up to in the improv space,” she says. “But I didn’t see many people who looked like me. There’s nothing like seeing someone who looks like yourself and seeing what’s possible for you. There’s just no substitute for that.”

Nwodim wanted to be that person for Baltimore kids. And she knew just who to reach out to.

Back in the mid-aughts, Todd Wade taught Spanish at Eastern Tech High. He remembers Nwodim, who was born in Perry Hall and grew up in White Marsh, as a great kid.

“Ego was a rock-star student,” he says. “She was so driven. She got straight A’s; all fives [the highest score] on her AP exams. But she also was this extreme extrovert, just super happy. She wouldn’t ever walk by a teacher without grinning and saying hi.”

He knew she would succeed in any path she chose. He never worried about her. Eventually Nwodim graduated and he left teaching Spanish to become the director of restorative practices and the peer mediation coordinator at City Springs Elementary/Middle School for the Baltimore Curriculum Project (BCP), a nonprofit that operates a series of solutions-based charter schools in Baltimore. Around the time of the George Floyd murder, Wade organized a Black Lives Matter (BLM) rally in Baltimore with his son.

“We thought 12 people would show up. It ended up being 3,000,” he says, still somewhat amazed. A white teacher from Baltimore leading people on a BLM march made the news—and it even reached Nwodim in New York.

She reached out to Wade and invited him to come see the show. His first thought: “What show?” Yes, he had no idea she was on SNL. He laughs with embarrassment at the memory.

“I don’t watch TV!” he protests. “I’m not a big pop culture guy.”

But he did go to New York, impressing his friends and family who had been trying, unsuccessfully, to get SNL tickets for years.

Of course, he was blown away by Nwodim’s performance that night.

“She’s really good,” he says.

After that, they stayed in touch a little bit. So when, during the writers strike last year, Nwodim came up with this idea to bring improv to Baltimore City schoolchildren, she immediately thought of Wade.

“I reached out to Mr. Wade—I guess I’m supposed to call him Todd now, because I’m an adult,” Nwodim cracks. And she laid out her idea.

It felt a bit like serendipity. Restorative practices is a mindset for how to handle discipline in school, Wade explains.

“It looks for the root causes of behavior.…And it’s a powerful tool to create a school environment where kids know they’re loved.”

Meanwhile, peer mediation is a practice that has students intervening in conflicts. They sit in a circle, they talk and express their feelings. It’s a bit like therapy. And yes, like improv.

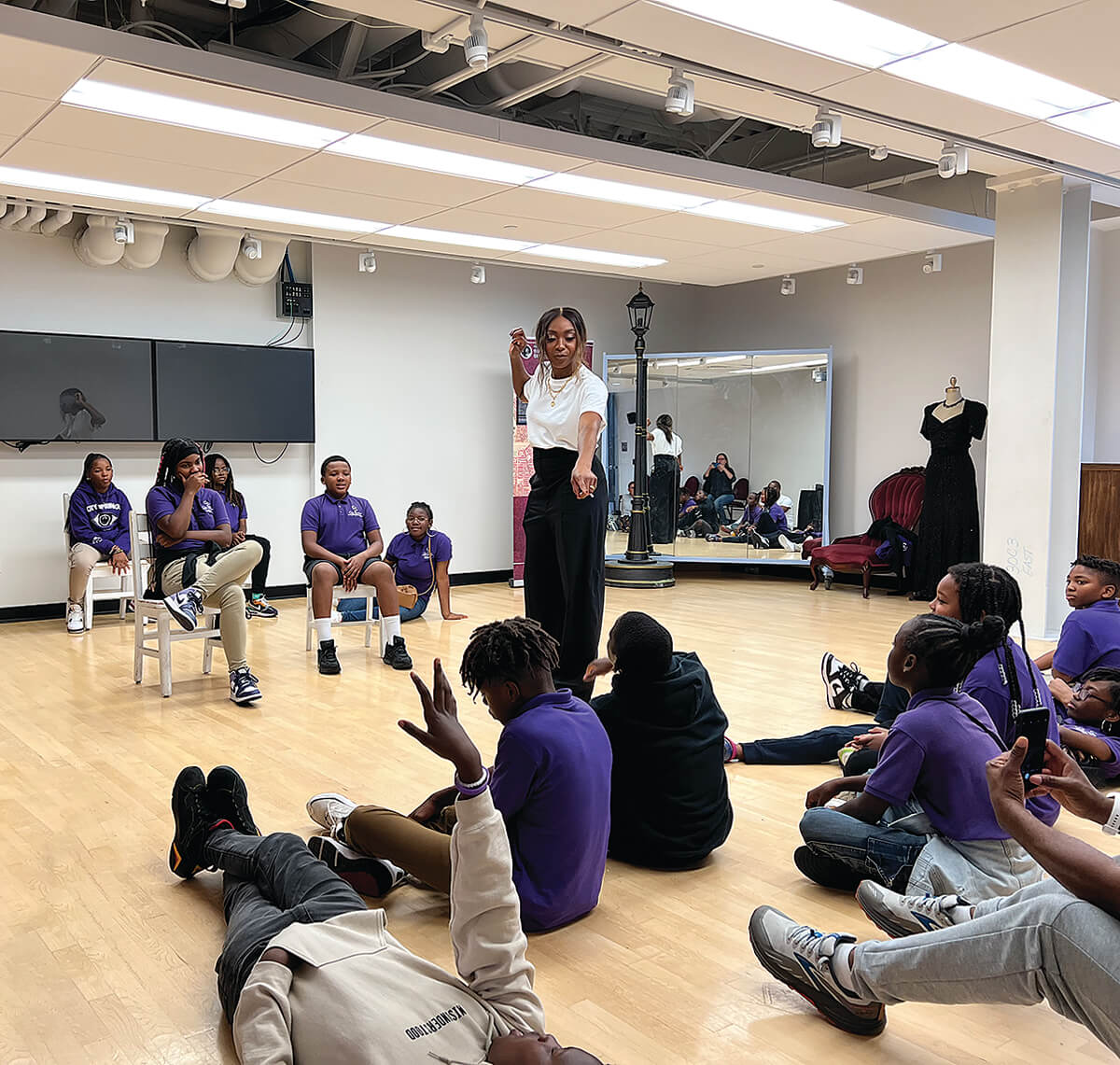

Arrangements were made quickly and, last September, Nwodim came back to Baltimore to teach improv to kids at the City Springs Elementary/Middle School in Southeast Baltimore, one of the charter schools run by the BCP.

The improv session itself would take place at Center Stage in Mount Vernon, but first Nwodim stopped by the school to talk to the peer mediators.

“I see myself in you,” she told the assembled group. “I was sitting in seats just like you are and had dreams of doing bigger things. I believe that each of you has inside you what it takes to make your dreams and visions happen. Despite what anyone might tell you…the sky is the limit.”

This message was particularly important to Nwodim. She wanted to show the kids what was possible. Maybe it would be improv. Maybe it would be something else. The idea was to explore and embrace the possibilities. The “yes and” of life.

Terrence Okoh, Taven Williams, and Kayla Austin are all 12-year-old sixth graders at City Springs Elementary/Middle School. They’re also trained peer mediators. They attended Nwodim’s talk at City Springs and then went to Center Stage for the improv session.

Today, they’re gathered in a City Springs classroom to talk about the experience. They confess they didn’t know who Nwodim was when she visited them, but they thought she was funny and cool.

“I was surprised,” Williams says. “Because there aren’t a lot of celebrities from Baltimore.”

The improv work they did that day isn’t necessarily what you might expect. Not scene work, per se, where two people act out a scenario and try to get laughs. It was mostly exercises that teach you to listen and collaborate, which are soft skills implicit in improv.

“One we did was called, ‘Zip, zap, zop,’” Okoh says. “Say if I ‘zip’ to you, you have to ‘zap’ to someone else and they’ve got to ‘zop’ to someone else.”

Wait, what?

“Do you want us to demonstrate for you?”

Okoh says, in an “adults need so much explained to them” voice. So they do, along with Wade, their chairs loudly scraping against the classroom floor as they arrange themselves

into a circle. “Zip,” Okoh says, pointing to Austin. “Zap,” she replies, pointing to Williams. “Zop,” Williams says, pointing to Wade. And around they go. It’s not as easy as it sounds.

“You can’t mess up,” Williams explains.

“And what if you do?” Wade prompts.

“You start all over.”

“You say, it’s all good,” Wade corrects, emphasizing the positive attitude one should bring to the exercise. “And then you start again.”

At Center Stage, they did another exercise that involved counting to 20 with a group of sixth graders. It nearly resulted in a mutiny. In this exercise, everyone sits in a circle (again). But this time, they lock arms, close their eyes, and count to 10. But here’s the rub: “No one can speak at the same time,”

Nwodim says of the exercise. “If two people say four, you have to start over again. So that was very frustrating because it required a level of quiet that I don’t think is inherent to young people. And you need stillness and trust. And so the frustration was that, oh no, two people have said the same number—we were so close and now we have to start over again.”

Some kids bolted from the circle. Others got into shouting matches. But Nwodim kept the whole thing under control.

“Ego was stunning,” Wade says (photographed below, on far left, with students). “She would have been an amazing teacher. A lot of actual teachers would’ve gotten very nervous in that moment. But she was just so patient and good with them.”

Somehow, she managed to corral the kids back to the circle—okay, maybe there was some bribing with Chick-fil-A involved. And they fulfilled the exercise.

“We were supposed to get to 20, but we did 10,” Austin says. But they still felt like they had really accomplished something. Together.

For her part, Nwodim was very impressed by the students. “They were wide open to participating in the games and putting themselves out there,” she says. “[This kind of exercise] is pretty vulnerable. They demonstrated, I think, a level of focus that I wasn’t sure was possible for a group of kids this age. They exceeded my expectations.”

And the City Springs students say the exercises taught them a lot.

“It teaches you to be an active listener,” Williams says, repeating a phrase that Wade uses often in the peer mediation training.

“It taught me to focus,” Okoh says.

“And to pay attention,” echoes Austin.

After the improv session, the kids did a little internet sleuthing to find out about their new hero.

“She was in Good Burger 2!” Okoh says, in awe.

Austin and Williams perk up. “She was?” Williams says.

“Yeah, she played the wife. And she’s in Pizza Hut commercials!”

“I bet she has, like, 12.3 million dollars,” Williams says.

All three say they were inspired by Nwodim’s visit. “It inspired me to do the right thing and not make the wrong decisions,” Okoh says.

“Some people from Baltimore choose the wrong decisions. But Miss Ego came and she talked to us about how to do the right things in life.”

The improv training went so well, and intersected so neatly with the work of the BCP, Nwodim and Wade knew they wanted to continue it. If Nwodim had her druthers, she’d be teaching every single improv class herself—she loves spreading the gospel of improv that much.

“Selfishly, I want to be at every single workshop,” she says. But she knows that’s not possible. So sometime this year, she’s going to come back and teach a group of teachers how to lead improv sessions. Improv will officially become part of the BCP programming. She also plans to take this training to students in New York City. But it’s especially meaningful for her to do this program here at home.

“I’m so happy I was born and raised in Baltimore,” she says. “I always say that I feel like it’s my brag. That I’m from Baltimore.”

She doesn’t get home as often as she’d like, partly because she’s so busy with SNL and other work and partly because her mother sold her childhood home. (“I was devastated.”) But she feels a real connection to the city.

“I held onto my Maryland license an illegal amount of time, because that was my one piece of home,” she says with a laugh. “And when people say they don’t know I’m from Baltimore, I get kind of offended by that. As a performer, I think [being from Baltimore] has given me a bravery and a confidence and a boldness. I like to think I behave like a Baltimore woman.”