Arts & Culture

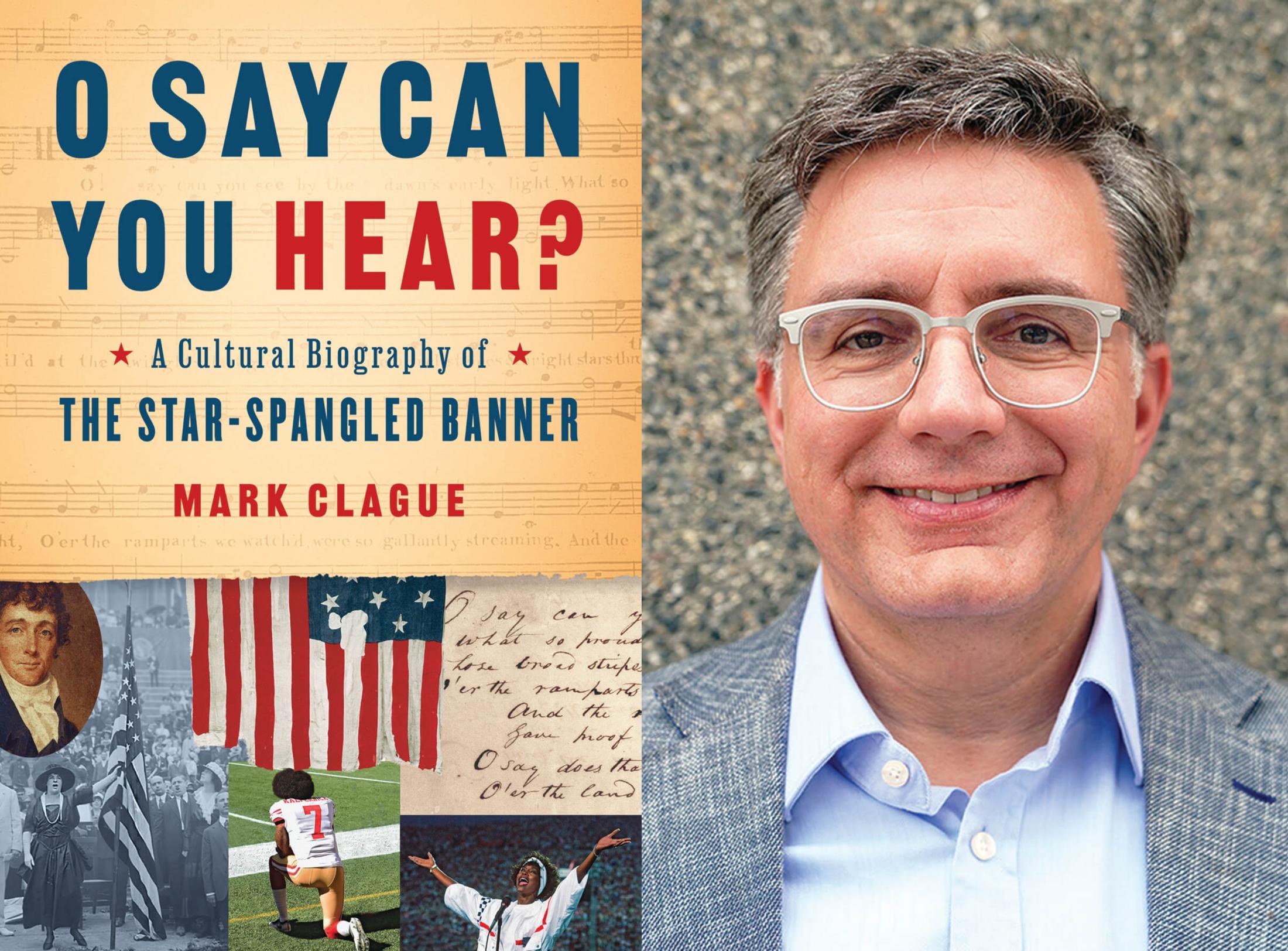

Mark Clague’s Cultural Biography of “The Star-Spangled Banner” Couldn’t Be Timelier

The musicologist chronicles the complicated history of the song that eventually became the country’s official anthem.

Baltimore has a unique bond with “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Of course, we were the home of seamstress Mary Pickersgill, who sewed—with assistance from her daughter, nieces, and a 13-year-old Black indentured servant—the giant flag that flew over Fort McHenry and inspired Francis Scott Key. The history of the song that became the country’s official anthem is complicated, however. As is the history of its author, a slave owner.

As musicologist Mark Clague chronicles in O Say Can You Hear?: A Cultural Biography of The Star-Spangled Banner, the anthem represents an evolution of a song originally titled “Defence of Fort M’Henry.” Rather than words or a tune frozen in time, “The Star-Spangled Banner” has been interpreted and arranged a thousand different ways in the cause of national unity, propaganda, and protest. In his deeply researched work, Clague thoughtfully addresses all of it—from the song’s early musical influences to its iconic renditions, and its use as a tool of patriotism and dissent. It couldn’t be timelier.

I have to ask this first. As a musicologist and historian, what’s your favorite rendition?

I teach a class on the history of music in the United States and one of the questions is, what is American music? I figured we’d start with Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock playing “The Star-Spangled Banner” because that’s got to be American. What’s interesting, is that as you unpack the song, you realize that it’s both patriotic and an act of protest at the same time.

That investigation of Hendrix’s performance eventually launched you into 10 years of research and the book. Correct?

That’s right. There’s an ambiguity, or maybe conflict is a better word [in Hendrix’s rendition]. That’s the power in the song—the ability to bring both forward. That got me interested in answering other questions about “The Star-Spangled Banner,” like, where did the music come from? What did it sound like in 1814? In terms of the most intriguing, powerful, confusing, and sort of amazing version, I would put Hendrix at the top. The most spiritually compelling, I think, is Whitney Houston’s version. I also love José Feliciano’s version.

Tracing the use and occasional repurposing of the song, which didn’t become the country’s official anthem until 1931, alongside various political, military, and social upheavals, provides an interesting frame for the book. For example, its performance during World War I as a loyalty test for German-American singers. Then John Carlos and Tommie Smith create perhaps the most iconic political protest around its playing at the Mexico City Olympic Games in 1968.

One of the things I love about studying the song is that you also learn about the almost chemical reaction between the music and the political context. The reason I call it a cultural biography is because I see this song as a kind of witness to history, being present in these pivotal moments in American life, being used as a symbol to motivate, to protest, and to amplify, to inspire. Those moments, I think, tell the story of America.

You spent a lot of research time in Baltimore. Any favorite local stories?

One is just how much earth is part of Fort McHenry. It’s not a wooden fort. Its ramparts are mounds of dirt. Then, there’s a moment in the battle where a British bomb crashes a wall and enters the room where the American military is storing all its gunpowder. But that bomb does not go off. If it had exploded, it would have exploded the powder in the fort and blown up the fort from the inside. That seems miraculous.

How do you understand Key, who enslaved people, enforced the Fugitive Slave Act as D.C.’s district attorney, and as a lawyer also represented individuals in court trying to free themselves from slavery?

He filed 106 separate cases on behalf of Black Americans. Somehow, he wanted the rights of property owners and plantation owners to be respected as well as the rights of Black Americans. He believed that there would be a way to end slavery peacefully. I think that’s what he was hoping for. Key died in 1843, but his family all ended up fighting for the Confederacy.

You open with an 1872 quote from Missouri Senator Carl Schurz: “My country, right or wrong; if right, to be kept right; and if wrong, to be set right.” There’s one similar quote from James Baldwin later in the book.

[Some] people treat patriotism in a very surface way. They treat it as a kind of mantra or expression of pride rather than a responsibility. I think of patriotic Americans as those who have invented the country that they wanted to live in.