On a tree-lined block of Bolton Hill’s Park Avenue reminiscent of Brooklyn Heights, old brick rowhomes built in the 1800s share a storied history. F. Scott Fitzgerald lived on the street after Zelda died, as did renowned classicist and author Edith Hamilton. And the late artist Les Harris raised his three daughters there with his wife, Sally, hosting dinner parties and transforming his house into a work of beauty and a small mecca for creatives.

Harris flocked to the neighborhood along with other artists and teachers in the 1960s because it was affordable (he paid $14,000 for his rowhome) and in close proximity to several schools, where he taught and studied—Maryland Institute College of Art, Johns Hopkins University, and the Schuler School of Fine Arts (he also taught art and theatrical design at the Park School, and Stevenson University). After Harris’ death in 2008, his wife continued to live in the three-story brick home at 1323 Park Ave., built in 1885, but she recently put it on the market.

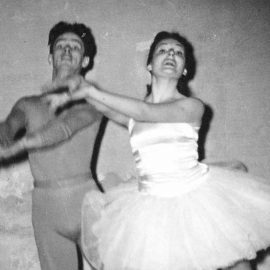

Harris was a Baltimore icon and a Renaissance man, full of magic and mystique. He and his wife were active across multiple artistic disciplines. They met when she hired him as a choreographer and set designer at her theater, The Gateway Playhouse, in Long Island, New York, where she grew up.

“It was a totally artistic household,” says his daughter Holly Harris, who spent the past two years boxing up the house. There was always someone playing the piano—which is still in the house—or painting or gardening.

Harris became known for his maximalist paintings exploring all manner of metaphysical thought, and much of his work is housed at his Amaranthine Museum in Clipper Mill, a space that reopened to the public in November.

But his house was a work of art, too. He designed and executed many renovations and decorative details: a brick basement that leads out onto a patio, a rooftop garden, a marble kitchen counter in the shape of a grand piano, a wrought iron railing running up a rear stairwell, coffered ceilings in three of rooms. Local artisans installed stained glass above the front doorway and above the handcrafted cabinetry in the dining room. His most obvious addition stylistically might be the long mural that wraps around the front hallway and stairwell, painted for the wedding reception of one of his daughters following a ceremony in the Brown Memorial Park Avenue Church across the street.

“The house is so filled with love,” says Holly, who was 1 when her parents moved there in 1962. “We had so many good times in there.”

His studio was in the basement, but when his paintings became larger in scale, he grew out of that space in 1976 and moved to a studio at Clipper Mill, which he also used as a museum to show his body of work, which he refrained from selling. When Clipper Mill sold in 2005, the museum relocated within the community and just last year relocated once again to a much smaller space. The family intends to sell his work, as they believe it will reach a wider audience.

To understand—or at least get a sense of—the man who said things like “matter is a superstition”—you must first go to Amaranthine, the legacy he left behind. Floor to ceiling paintings and sculptural work (including pieces hung from the ceiling) move through time and explore metaphysics through the lens of art—numerology, astrology, cathedrals from various eras—going from modern times all the way back to the origin of consciousness, as he understood it (the paintings are heavy with sacred geometry and hieroglyphics), perhaps developing his own cosmology along the way.

“He was gonna find God through the eyes of artists,” Holly says. “His search was for the divine in everything.”

Through the Age of Aquarius, the Age of Pisces, the Age of Romance and the Age of Reason—they all have their place among the work.

“Once he was inspired, he’d paint so fast,” Holly says. “Nothing here has two coats of paint.”

She also recalls how the rooms of the Park Avenue house changed often, each time her father got a new vision that “he had to fulfill” and would move things around and redecorate to realize his ideas. Sections of the house went under complete renovations repeatedly.

Antithetical to what is done today, he would paint the grand 12-foot ceilings in a darker hue to create more intimacy in the large rooms.

Growing up, Holly was surrounded by national and international artists and actors, she says. Her parents would habitually host people when they were in town for gigs.

They bought another house in Virginia in 1992, where his artistic eye went into landscape architecture, as he transformed nearly two lakefront acres into their second paradise.

“He was always all over the place,” says Holly. “Mom and Dad never looked back; they just kept going, kept building.”