Arts & Culture

Pop Goes the Library

After donating much of his vast comic book and memorabilia collection to the nation's library, Steve Geppi sits down for a lively conversation with librarian of congress Carla Hayden.

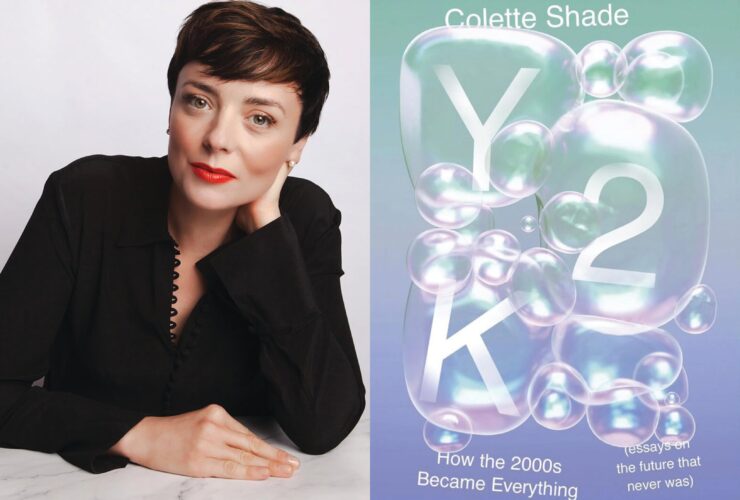

Steve Geppi loves sharing his life story. Sometimes he begins in the middle, talking about the times works from his comic book collection were sold to Hollywood stars Leonardo DiCaprio and Nicolas Cage. Other times, he goes back to the beginning, when he was a kid from Little Italy whose mother didn’t have much, but still managed to buy her beloved boy 10-cent comic books. Always, he shares some part of himself, because it’s a Horatio Alger story if ever there was one.

Steve Geppi loves sharing his life story. Sometimes he begins in the middle, talking about the times works from his comic book collection were sold to Hollywood stars Leonardo DiCaprio and Nicolas Cage. Other times, he goes back to the beginning, when he was a kid from Little Italy whose mother didn’t have much, but still managed to buy her beloved boy 10-cent comic books. Always, he shares some part of himself, because it’s a Horatio Alger story if ever there was one.

Photography by Sean Scheidt.

Geppi’s life has followed an unlikely trajectory from high-school dropout to mail carrier to comic book store owner to comic book distribution titan to serious collector. Along the way, he amassed one of the largest private collections of vintage comic books and pop-culture artifacts in the world.

Not surprisingly, Batman is his favorite comic book character—a superhero with no natural superpowers who uses his substantial wealth for the greater good.

“I didn’t know I was poor when I was growing up,” says the entrepreneur as he walks around the now-closed Geppi’s Entertainment Museum [G.E.M.], which housed his collection of some 6,000 comic books, original art, buttons, pins, badges, and other collectibles. “Until I got into Calvert Hall and my mother couldn’t afford the $400 a year tuition. When my dad left, things got so bad that my mother had to go on food stamps and welfare. I had to quit school at 13, and I became the patriarch of the family.”

Geppi, owner and CEO of Baltimore-based Diamond Comic Distributors—the largest distributor of English-language comic books in the world—and publisher of Baltimore magazine, is now writing the latest surprise chapter of his inspiring 68-year narrative. In late May, he announced the closing of his 12-year-old museum and the donation of some 3,000 items and artifacts—valued in the multi-millions—to the Library of Congress, where his dear friend Carla Hayden (former chief executive officer of Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore) is the librarian. It’s the biggest comic books and related collectibles gift in Library history, adding to what was already the largest collection of comics and related ephemera in the world.

Not surprisingly, Batman is his favorite comic book character— a superhero with no natural superpowers who uses his wealth for the greater good.

Months in the making, it all began about a year-and-a-half ago with Geppi’s visit to Hayden at the Library of Congress for an exclusive viewing of original 1962 illustrations of Amazing Fantasy No. 15 (the historic comic by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko that depicts Spider-Man for the first time). The D.C. trip piqued Geppi’s interest in the nation’s largest library, which houses such varied treasures as Thomas Jefferson’s Library, Charles Dickens’ walking stick, a lock of Beethoven’s hair, the papers of 23 presidents, and a Gutenberg Bible. In fact, he was so impressed with what he saw, it was the catalyst in his decision to donate as he got his estate in order.

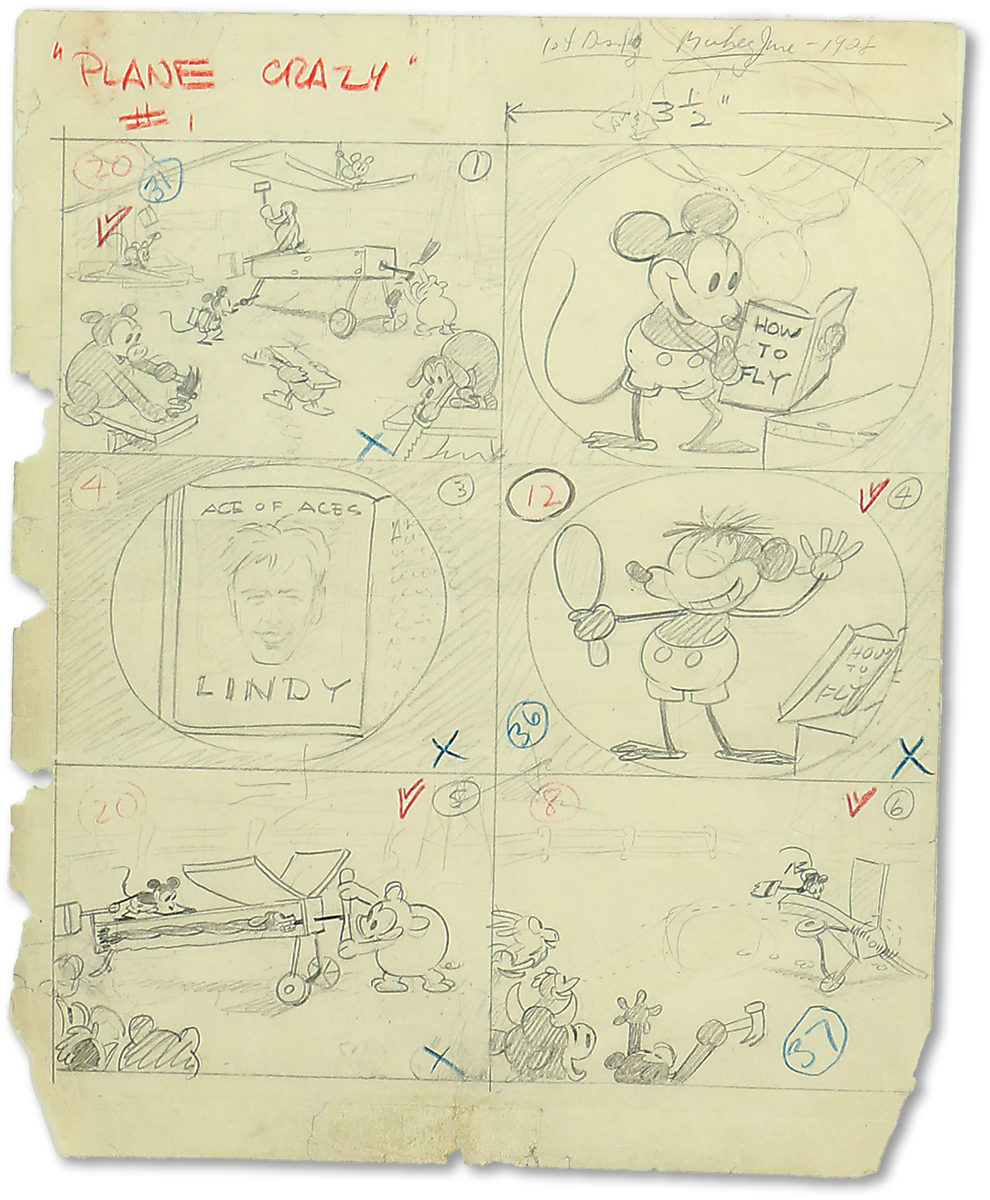

The timing was fortuitous, as Hayden herself was in the midst of securing funding from Congress and other sources for enhancements to the Library both in Washington, D.C. (including a new youth center), and online. As part of the updates, Geppi’s collection, including six original storyboards detailing Walt Disney’s 1928 animated film Plane Crazy (the first Mickey Mouse short to be produced), printing blocks from Richard Outcault’s fin-de-siècle comic strip “The Yellow Kid,” and rare Superman and Batman comics will get a new permanent, prominent home. Selected items from the collection will be on display at the Library this summer.

As the mint-condition collection gets ready to come off the walls and out of the cases in preparation for the move to D.C., we sat down with Geppi and Hayden at Geppi’s Entertainment Museum for this historic event. For several hours, they talked about comics, literacy, and even Shakespeare. The two finished each other’s sentences, held hands during a photo shoot, and had the kind of chemistry that comes when two people genuinely admire one another. “I can’t even name any previous Librarians of Congress,” says Geppi, laughing. “I hope you stay there forever—you’re the right person.”

The donation has also prompted the comic book king to think about his own legacy. “When people visit, there’s going to be Jefferson’s Library and the Stephen A. Geppi Collection of Comics and Graphic Arts,” he says. “And visitors are going to ask, ‘Who’s that Jefferson guy?’”

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden and Baltimore publisher Steve GEppi talk about his collection at geppi's entertainment museum. the original G.I. Joe prototype courtesy of comic wow.

Carla Hayden: I remember discovering books at a young age. When I read Bright April, it was the first time that I saw anyone who looked like me.

Steve Geppi: Books are what connects us.

CH: I think about the times that I used to see Betty and Veronica in the Archie comics. As a middle-schooler, you aspired to be Betty and Veronica. They were so cute!

SG: In fact, [former Maryland State Superintendent of Maryland Public Schools] Nancy Grasmick loved Archie comics, and she was responsible for us meeting. Comics are more intellectual than people would ever know. There are famous writers who tell me they collect comics. I’ve had customers who were astronauts. When I met President Clinton, he told me he loves comic books.

CH: When we talked about your collection, we talked about how more people are saying that comics are a gateway to literacy.

SG: In the past, people thought the opposite . . . .

Photography by Sean Scheidt.

CH: Why were comics seen as subversive?

SG: They had a Senate investigation to investigate the comics as to whether they were really good for children. They said it would make you a juvenile delinquent. It really crippled the comic industry in the ’50s. So ever since our industry came along, the comic store industry—or direct market is what we call it—it has been my crusade for 45 years to give them the respect and credibility they are due.

CH: It’s the same with public libraries. There was this taboo about letting kids have comic books. And then there was the realization that they are a gateway to introducing them to other books. Captain Underpants [writer and illustrator] Dav Pilkey talks about how he had difficulty reading, and he loved comic books and got into illustration, so there’s this recognition. And now comic books and graphic novels are in libraries, but it took a while.

SG: Journey to the Center of the Earth was one of my favorite movies. When I read the comic book, I wanted to read the book. I couldn’t get enough. If Jack and Jill went up the hill, kids might not care. But if Spider-Man and The Hulk went up the hill, now you’ve got their attention. The example I always give is if you’re sitting on the train and a guy in a suit is sitting there reading a science-fiction paperback and a dressed-down guy is reading a comic book, they’re both reading about little green men. The packaging is what misleads people.

SG: When I was 5 years old, everywhere you went, you ran into comics. They were in drugstores. They were in grocery stores. So when you’d say, ‘Mom, what did you get me?,’ it was a comic book. Who would think you could learn from an Archie comic?

CH: You can.

SG: I was reading Archie and they were out on an exploration and they were spelunking. What the hell is spelunking? I had to look it up.

CH: They started putting Shakespeare in comic books. That’s a way that you can introduce it and get kids involved. The next thing you know, it’s like, ‘Yeah, Macbeth!’ And in recent years, there has been more recognition of dyslexia and young people with reading difficulties. That has also helped show that visual literacy is just as important as other forms of literacy. You can read a picture, you can read an illustration—just like you can plain text. That’s why I was so excited when I first went to the Library of Congress and they were telling me about all of the wonderful collections, and they mentioned comics and I said, ‘Do you know in Baltimore there’s this wonderful gem?’ I invited you to the Library because I wanted to show off. I knew you would appreciate it.

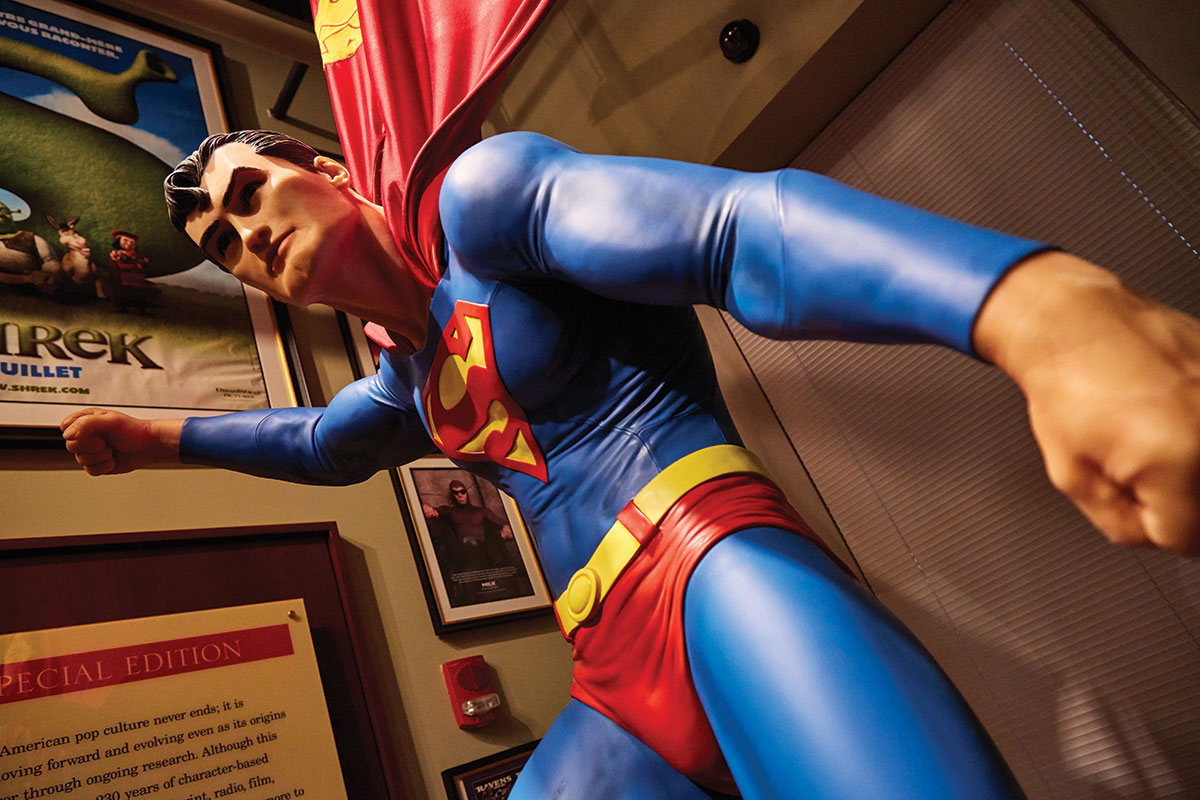

a towering superman figure.

SG: Someone anonymously donated Amazing Fantasy artwork to the Library of Congress. They had donated the original artwork that no one thought had existed. Paul Tiburzi, one of my attorneys, said, ‘Why don’t we go down and see Carla?’ because I hadn’t seen you since you became the Librarian of Congress. You pulled out the red carpet for me. I was in heaven.

CH: And what was so fascinating for me is that we have all of these experts. When the curators were showing you what they had, they were learning things from you. You knew some of the artists. You knew the history. You added to their knowledge—they loved you. Now they are able to give more context to what we already have, and they know some of the inside stories. The addition of the collection is not just how many things we will have now, it’s the depth.

SG: When you brought me down, we didn’t get into [the idea of the donation] per se. But later, you threw out the first pitch at Camden Yards.

CH: It was against the Nationals.

SG: We were at the Diamond Tavern at the Hilton and were having a couple of pre-game drinks. . . .

CH: (laughing): . . . It was sodas.

Photography by Sean Scheidt.

SG: I’m finishing your sentences, and you’re finishing mine, and it’s like someone was grabbing us by the nape of the neck and saying, ‘You guys need to talk.’ And at my age now, I’m doing estate planning. And I thought, ‘My kids are fine financially, but my collection, which they appreciate and love, is going to be a kind of a burden to them.’ They don’t want to hold on to it forever. And I thought, ‘Where can it go?’ And then it started to crystallize.

CH: When we move the collection, this will be a major, major move. They are like the crown jewels. It will have to be at a certain time and only a few people will know where things are being transferred and where they are going. The collection will have to be held in secure places. At the Library of Congress, we have the contents of Abraham Lincoln’s pockets from the night he was assassinated. But what is so significant, and what will inspire people, is that this comic art will be getting that same attention.

SG: See, this is my goal—if comics are not treated as valuable or important, people will see them as less valuable and important. The Library of Congress is the quintessential permanent resting place.

CH: . . . guarded by the Capitol Police, the people who protect Congress.

SG: Along with the Gutenberg Bible. And the Jefferson Library. All of this stuff is being elevated in the same way—and comics deserve it.

CH: And think about young people who are comic book lovers and who are isolated or considered geeky or whatever. This will make them feel like they belong.

SG: Here’s a good example, Carla. One day I’m at San Diego Comic-Con and a guy introduced himself, and I said, ‘I know who you are. You’re Dave Dorman. You do all those covers for Star Wars.’ He says, ‘No, you don’t know who I am.’ He said, ‘Remember that little kid who used to come into your store? That was me.’ And he starts telling me all these stories about my store. Here’s a kid, maybe, who if he’d never had a store to go to, who knows what would have happened? I feel very blessed to have been a part of it.

Photography by Sean Scheidt.

CH: You have inspired us to do something on why people collect and what they collect. It all started with Thomas Jefferson’s collection, so there’s going to be a section on collecting.

SG: It’s fascinating what people decide to keep. Collecting teaches you how to take care of things. But kids don’t get exposed to comics the way that they did when I was a kid. I always had an active imagination, and I wanted to learn—that’s why it was so frustrating that I had to quit school, because I loved school. My biggest dream in life was to get a full set of encyclopedias. My mother couldn’t afford a set, so when comics came along, they were 10 cents, and my mother could afford to buy them. I was mesmerized. I would sit on the couch with the fan blowing and my mother would make me a hamburger—and I’d read.

CH: Well, it’s memory. Also, you’re talking about your mom and your mom bringing something that’s a tie-in to literacy, too. It’s the human contact.

SG: The worst thing you could ever do is be a dealer and a collector—you don’t want to sell what you collect. When I started collecting, I needed to make a living, so when times were tough, I’d have to sell things that I didn’t want to sell. And even though I might get them back one day, and even though I would buy them back for more, I would sell them for more.

CH: When did you realize that your collection was really to the point where you had enough to invest in displaying things?

plane crazy storyboard courtesy of comic wow.

SG: What crystallized it were the Mickey Mouse drawings. When I got them, I had them in my vault and started feeling guilty about having them in my vault, and all of a sudden [museum founder and “Beetle Bailey” comic strip creator] Mort Walker comes to me to solicit money for the then under-construction IMCA [The International Museum of Cartoon Art]. I thought, ‘Now here’s an opportunity for the world to see them.’ It got press like you wouldn’t believe. They were called the Mona Lisa—people came from everywhere to see them. And when the museum closed, I had to buy back what I had given them. So now I have them back in my possession. That was the catalyst for me—when I first recognized I had almost too much for one person to own. If you’re sitting there looking at it, but nobody sees it, what good is it?

CH: That’s called a miser or a hoarder. See, you’re not selfish. You want to share your love of it and your knowledge of it.

SG: Thank you. There’s a lot of ego you could associate with this, but I’m trying to be modest—the biggest ego trip I ever got out of this is that I was at Disney and saw a Xerox of [the storyboard], and I was like, ‘I own this.’ Somebody needed to save this stuff for all time, and I was just lucky enough to be in the position. I was just lucky enough to be that guy. Not only is this 45 years of my life, I’ve had the privilege of buying the collections of [others]. This is an amalgamation of a lot of peoples’ lives.

CH: That’s your gift to the nation.

SG: When we were closing my museum, I knew there were some teary eyes. And I said, ‘We’ve had the exclusive for 12 years.’ To have the first drawings of Mickey Mouse is just too overwhelming. I don’t want to sound too pious, too humble, but it’s the truth. It’s like owning Jesus’ sandals or something—you’re not supposed to have that, not that I’m comparing Mickey Mouse to Jesus’ sandals.

CH: But you are a guardian. You save stuff.

SG: The day we bought the Orioles, Peter Angelos referred to the Orioles as a treasure. He said that we are just caretakers. It’s kind of the same thing here. You know that you’re going to die and that no one lives forever.

CH: But what you did could live forever.

Photography by Sean Scheidt.

SG: That’s the point. I was allowed to have this stuff, to enjoy this stuff. And if I had that much enjoyment out of it, other people will get a kick out of it, too.

CH: We are working on a treasures gallery, so the Gutenberg will be in there, but that is where Mickey will probably be, because that’s a treasure. If that’s the Mona Lisa, it should be in the treasures gallery.

SG: Mickey and Gutenberg are a pretty good combination.

CH: The Jefferson Building [where the collection will be housed] opened in 1897. It was the first federal building to be wired for electricity, so everything is about American creativity and ingenuity in this building.

SG: When I see it there for the first time, I don’t know how I will react. I will probably cry.

CH: You’ve collected this stuff all of these years—now let’s show it and share it.