Music For The People

On the brink of its 100th anniversary, the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra explores its legacy.

Music director Marin Alsop leads the symphony at a rehearsal for the operetta Candide.

A man in a vibrant purple velvet coat and matching pantaloons pirouettes in front of shelves where priceless violins wait to be cradled in their owners’ hands. From time to time, men and women in wigs resembling shimmering wedding cakes rush to and fro, nearly colliding with musicians who gingerly carry their clarinets and French horns onstage for rehearsal. A stage that normally holds carefully arranged chairs and a podium will now be the site of sword fights and dances, not to mention furniture and an enormous video screen.

During this week in June, the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, home of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, has been transformed into an opera house for the final production of the season—a partially-staged version of the operetta Candide. When the lights next illuminate the 77 musicians and music director Marin Alsop this fall, the symphony will enter its 100th season. This is no small feat—in an era when symphonies around the country are closing their doors permanently, the BSO is one of only 25 of the 800 or so U.S. orchestras to have reached this milestone.

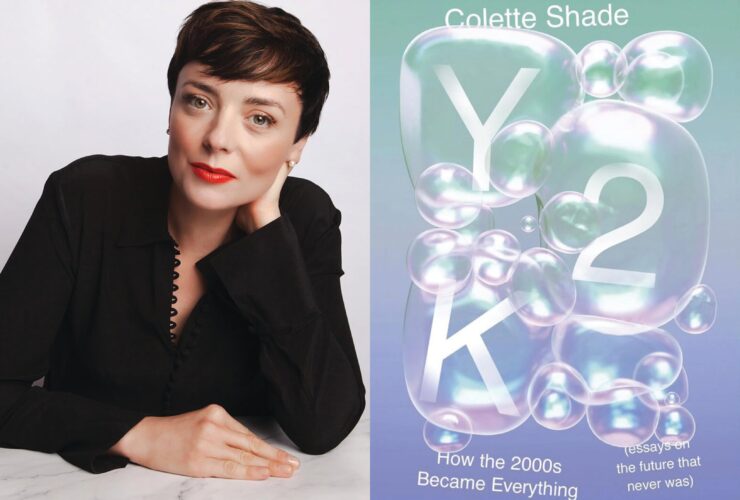

Philanthropist Joseph Meyerhoff contributed $5 million, a third of the cost, to build the 2,443-seat symphony hall, which now bears his name.

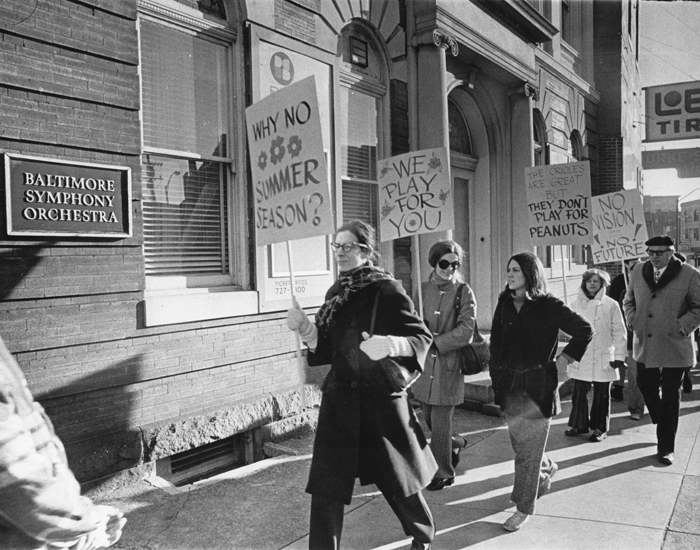

Musicians and the administration clashed during weeks-long strikes and a lockdown in contract negotiations during the 1970s and 1980s.

During the early years, the symphony played at the Lyric with what looked like scenery from opera performances as its backdrop.

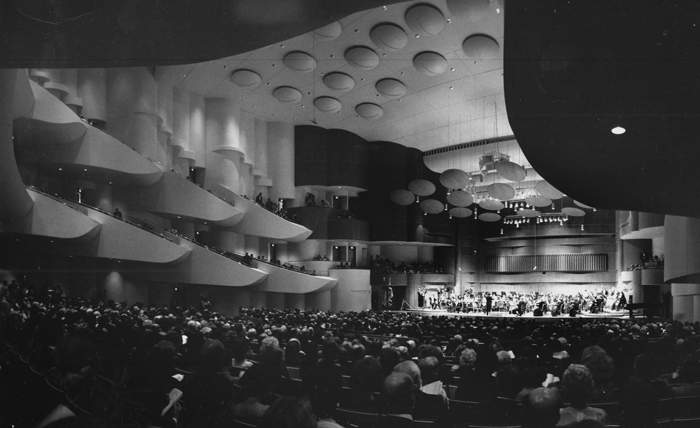

An overall view at the Meyerhoff symphony hall during a BSO performance.

During the 1940s, the orchestra took regular tours up and down the East Coast from Canada to Florida in three Pullman cars, stopping in orange fields for picnic lunches.

The orchestra after its return flight from Tallahassee, FL, while on a nationwide tour.

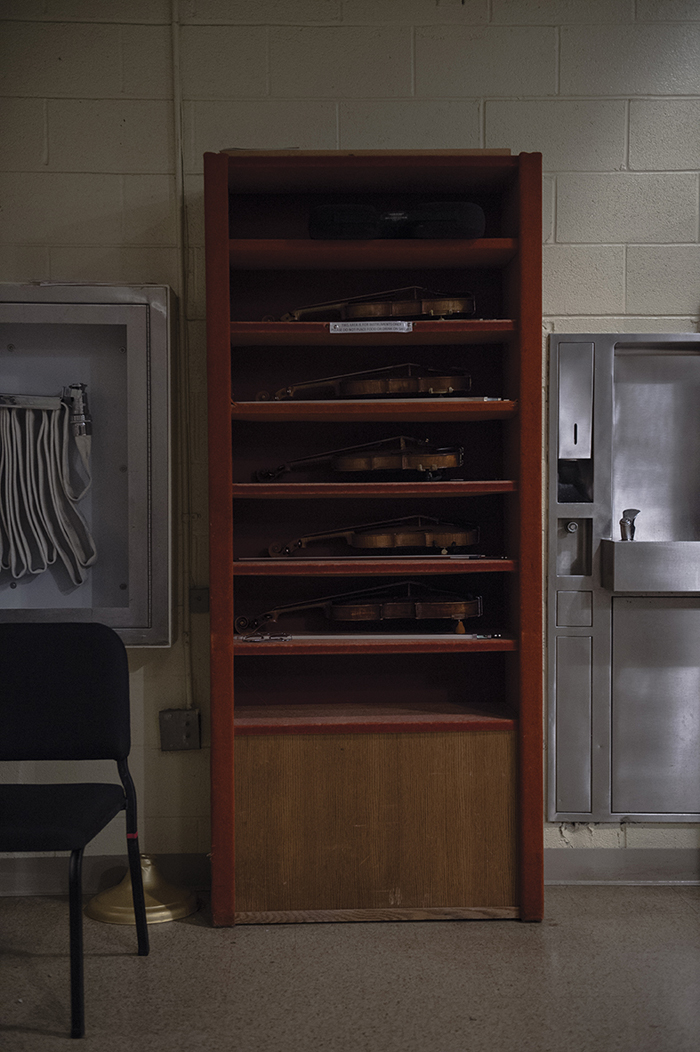

Violin storage backstage at the Meyerhoff Symphony Hall.

Music director Marin Alsop interacts with an orchestra member during a rehearsal.

The orchestra's music sheets light up during a rehearsal for Candide.

A performer sings in Candide, while Alsop conducts her orchestra in the background.

Performances that necessitate such elaborate backstage scenes, like Candide—based on the satirical novel by Voltaire and composed by Alsop’s mentor Leonard Bernstein, who selected her to study with him as a young conducting student—are becoming more common for the BSO. It’s part of an effort to bring in audiences that wouldn’t normally flock to see symphonies or concertos.

However, the presence of 13 singers and actors and a chorus of 83, not to

mention choreographers, directors, and wig mistresses, lends a slightly chaotic air to the stately concert hall. The stage directions and planned

interactions between the musicians, Alsop, and the performers are still being worked out. During the first dress rehearsal, Alsop, freshly back from

conducting in Europe, is a tad surprised when Keith Jameson, the man playing Candide, reaches for her baton to strike down a pressing foe. It’s not an

improv, but a new addition to the script that the maestra was not aware of. Garnett Bruce, the operetta’s director, quickly interjects, “My apologies,

Marin.”

On the cusp of its centennial, this slightly frenzied atmosphere is felt across the symphony, from the concert hall to the boardroom. The BSO is striving

to remain relevant and establish its legacy in the burgeoning Baltimore arts scene, and it has lofty goals—attracting younger, more diverse audiences, and

defining its place in the community, for instance. But plenty of questions exist about the future, including how will classical repertoire evolve? What

role will the symphony play in the community? And how will the symphony make the money it needs for survival?

Members of the Baltimore Choral Arts Society and the BSO’s bass section during the run-through.

“When you look at how far the orchestra has come, in terms of its humble beginnings to where it is today, it’s very hard to predict where we might be in 100 years,” says BSO president and CEO Paul Meecham. “I would hope that we’re thriving, of course, but that we’re building a love for music with the youngest generations that will stand us in good stead in terms of audiences for future generations. It’s got to start young.”

This focus has been central to the symphony in recent years, from community outreach programs such as OrchKids—a during-and-after-school music program that reaches children in some of Baltimore’s poorest neighborhoods—to a just-debuted concert series with local public radio station WTMD called Pulse that pairs the symphony’s musicians with up-and-coming indie-rock bands. That commitment has made the symphony a national trendsetter, says Jesse Rosen, president and CEO of the League of American Orchestras.

The BSO has “really been in the forefront of the evolution of American orchestras in the 21st century,” he says. “It has a very distinguished past, but in recent years, we think of them as being a leader in the adaptive work of becoming more part of 21st-century life.”

As Meechum alludes to, the BSO is no stranger to defying the odds. It fought hard to establish itself as one of the premier symphonies in the country—weathering strife between management and the musicians’ union, as well as financial woes, most recently during the economic downturn, a time when many other symphonies and Baltimore cultural organizations folded under pressure.

“The Baltimore Symphony has always been the little engine that could and can,” says Michael Lisicky, one of the orchestra’s oboists, and an author of a new history of the BSO, Baltimore Symphony Orchestra: A Century of Sound, out in November. When it comes to the future, “you get the idea that no one knows . . . the whole thing is still an unknown.”

But, he notes, it was also unknown in 1916.

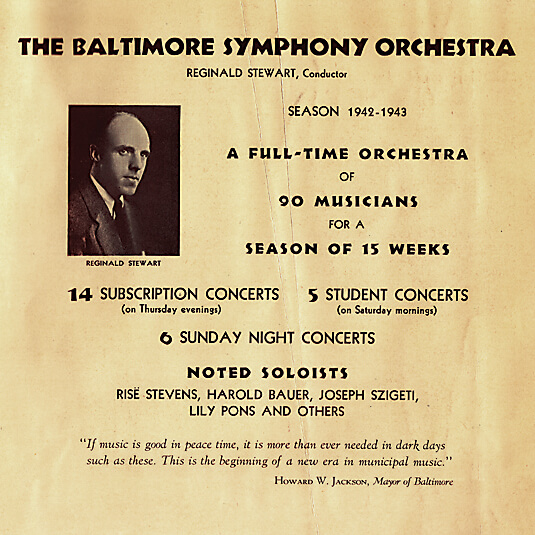

A program from after the BSO’s re-launch in 1942, featuring the conductor who created the blueprint for the orchestra today.

On February 11, 1916, the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra performed its first concert to a standing-room-only crowd at The Lyric. The program started with Beethoven’s classic Eighth Symphony.

A writer for The Sun noted that the night represented a turning point in the musical life of Baltimore. “It is not too much to believe that in the course of time, an orchestra that will take its place with the most important organizations in the country will result from the beginning that was made at the Lyric last evening.”

The symphony began with a $6,000 grant from the city, and was an arm of the Department of Municipal Music, which was folded into the recreation and parks department. Along with other venerable Baltimore institutions—The Baltimore Museum of Art, for example—city leaders, including Mayor James Preston, wanted the orchestra to enrich the public and bring the city prestige.

Though the connection with the city provided stability, it was also limiting, in terms of the types of musicians the symphony could attract—especially as it tried to fend off the esteemed Philadelphia Orchestra, which had a concert series in Baltimore until 1980. The financial confines led to several of the earliest conductors resigning, as well as conflicts with the musicians.

That crescendoed in 1942, when the symphony disbanded after only one performance that season. Thankfully, that same year, Peabody Conservatory director Reginald Stewart had an idea to make the symphony a private entity, and he drew up a viable blueprint for the new BSO, which went back to performing that November.

Despite the conflict, the symphony had plenty of successes in those early decades. It was the first in the country to offer a youth concert series in 1924, performed at New York’s Carnegie Hall in 1947, and, in 1945, became the cultural ambassador for Maryland. That same year, it took regular tours up and down the East Coast from Canada to Florida in three Pullman cars, stopping in orange fields for picnic lunches.

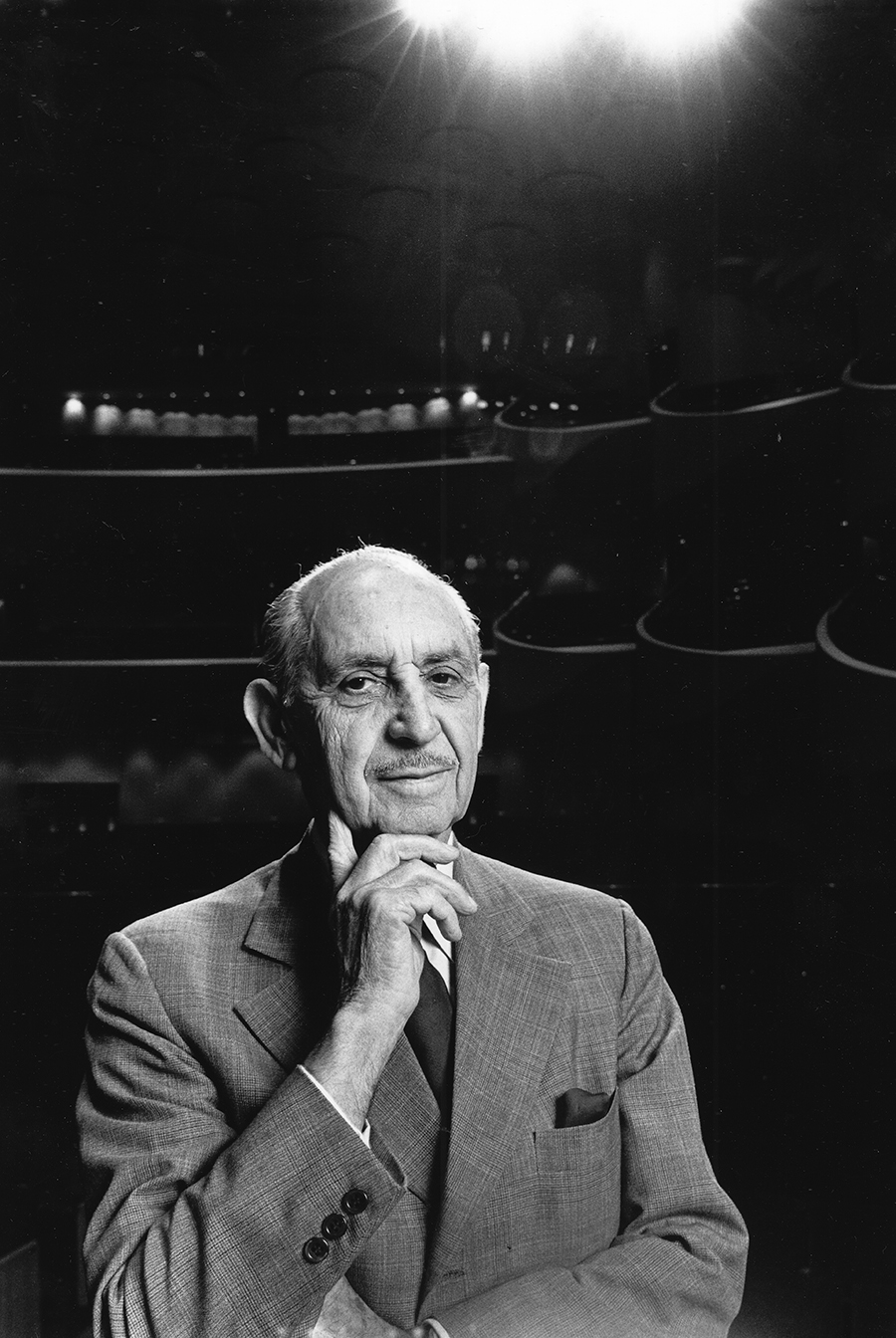

Then-music director Sergiu Comissiona during construction of the Meyerhoff in the 1980s.

The orchestra also made an effort to connect to its Baltimore audience beyond the concert hall, performing outdoor programs for the community that featured popular songs of the day.

Yet it wasn’t until 1969 that the BSO made strides in terms of quality, and that came with Romanian conductor Sergiu Comissiona. He brought a cachet to the position and transformed the symphony from a regional ensemble to one with an international reputation, Lisicky says. “Like when Diana Ross and the Supremes went from being just the Supremes, the BSO became the BSO and Comissiona.”

Music To Our Ears

Here are our picks for the not-to-miss performances of the BSO’s centennial season.

Romeo and Juliet

Friday, Oct. 16 through Sunday, Oct. 18. Times vary.

Prokofiev’s lush ballet gets a new treatment as the music is paired with actors performing scenes from Shakespeare’s classic play.

A Night of Vivaldi

Friday, Nov. 6, 8:15 p.m. and Saturday, Nov. 7, 7 p.m.

BSO soloists perform two of the Italian composer’s concertos, as well as movements from the Four Seasons, which reigns as some of the world’s most recognizable classical music. The night ends with a piece by Baltimore native Philip Glass.

Pulse with Wye Oak

Thursday, Nov. 12, 7 p.m.

A joint production of the BSO and WTMD, this innovative new series pairs BSO musicians with indie-rock bands, such as local duo Wye Oak.

Hilary Hahn

Thursday, Nov. 19 through Saturday, Nov. 21. 8 p.m.

Baltimore’s own internationally renowned violinist performs Dvorak’s violin concerto.

100th Anniversary Concert

Thursday, Feb. 11, 2016, 8 p.m.

Superstar violinist Joshua Bell is featured on a program that marks the night, 100 years before, when the BSO’s first concert was held.

Porgy and Bess

Friday, April 8, 2016, 8 p.m. and Sunday, April 10, 2016, 3 p.m.

One of the most beloved American operas by George Gershwin—think the iconic song “Summertime”—gets a concertized treatment by the BSO and the Morgan State University Choir, directed by Center Stage’s Kwame Kwei-Armah.

Yo-Yo Ma

Wednesday, June 15, 2016, 8 p.m.

The acclaimed cellist—who has won two Grammys with the BSO—returns to the Meyerhoff to play Dvorak’s cello concerto. The orchestra also performs the composer’s “New World” symphony.

It was under his tenure in 1982 that the symphony moved to a new home. At The Lyric, musicians had to crowd into a backstage packed with props—a harbinger of their future Candide extravaganza, as it turned out—and during the early decades, the symphony played with what looked like scenery from opera and theater performances as its backdrops. Increasing its season to 52 weeks, which would establish it as one of the country’s major orchestras, couldn’t happen because of the Lyric’s schedule and because it was not a state-of-the-art venue.

That’s where Joseph Meyerhoff came in. The philanthropist contributed $5 million, a third of the cost, to build a 2,443-seat hall, which now bears his name. The new space could not have been more different from The Lyric, which is old-world and ornate. The Meyerhoff instead has elegantly modern, unadorned wood accents and superior acoustics.

With lauded music directors David Zinman and Yuri Temirkanov, it continued touring internationally with major soloists such as Yo-Yo Ma.

Then, in 2005, Marin Alsop was appointed music director, becoming the first woman to head a major American orchestra. The details of her hiring infamously played out in the public eye, with the musicians’ union expressing displeasure at her appointment, as members felt the administration had moved without seeking their final approval. This was not the first clash between the musicians and the administration, with weeks-long strikes and a lockdown in contract negotiations during the 1970s and 1980s.

Both sides aired grievances, and the dust from that period appears to have settled—during our interview with her, Alsop joked that the job hadn’t brought any surprises, “after the beginning.” Lisicky notes that the orchestra had a re-start when Alsop arrived, “and it was important to do that. It’s hard to get past feelings. This orchestra’s very good at carrying baggage, and there is baggage that keeps going around the carousel that no one picks up.”

The interior of the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall.

Despite the rough start, Alsop’s presence at the helm has brought continued excellence, with more recordings and Carnegie Hall appearances. By founding OrchKids and launching the BSO Academy, a week-long program in which amateur musicians play side-by-side with members of the symphony, she has increased community outreach. And she has focused on bringing the music of modern composers, particularly women, to the symphony’s repertoire.

“Marin’s programming is very much of our time,” says Rosen of the League of American Orchestras. “Her substantial devotion to music by living American composers, and presenting work that very clearly ties into issues in our lives today, really positions [the symphony] as a leader.”

What has also defined Alsop’s tenure is her connection with Baltimore. “She’s been a great face for the orchestra to the community,” Lisicky says. “To them, she’s just ‘Marin.’ ”

Still, the orchestra’s touring was cut short after the BSO drastically lost money from fundraising and ticket sales following the economic downturn—its budget dipped to $24 million in 2010 from a high of $30 million in 2005-2006. There were furloughs, a staff reduction, and pay cuts. Around the country at the time and in the years that followed, other orchestras were facing similar challenges: Symphonies shut down in Albuquerque, NM; and Honolulu, HI; the Nashville Symphony came within days of foreclosure on its symphony hall; even the storied Philadelphia Orchestra filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Baltimore also watched its opera company slip into bankruptcy in 2009.

Meecham says the symphony is more stable now, and the budget has almost returned to $27 million, close to where it was before the downturn. Alsop calls financing one of the biggest challenges facing orchestras.

“We don’t have the luxury of saying, ‘Let’s try this, and we can afford to miss,’” she says. “I think if someone backed up a truck filled with money and dropped it off, we’d still have some challenges, but I don’t think we’d have too many. . . . We have to do everything with an eye on the bottom line, and I think that makes it hard.”

Soprano Lauren Snouffer belts out a high note as the character Cunegonde in Candide.

When the audience watches the symphony perform, it appears so pristinely coordinated—the bows of the strings slicing the air in the same direction, horns rising to brass players’ lips in unison, the musicians themselves dressed in refined black dresses and tails. It’s astounding that 77 musicians can play together with such precision, creating one, cohesive sound that at the same time consists of so many distinct layers. Watching them, you understand what has captivated classical music lovers for centuries.

It’s easy to picture the symphony and Alsop, who perform together so seamlessly, as one entity. But, in fact, the BSO is an organization of many moving parts—the administration, which includes a staff of 106; the board, which, along with the administration, is responsible for the fundraising that keeps the symphony afloat; the musicians, who are represented by a union known as the players’ committee; and Alsop, who juggles conducting at orchestras around the world with her duties at the BSO.

As demonstrated by Alsop’s beginnings with the symphony, at times, these groups have different ideas about how the symphony should run. That became news fodder this spring when many musicians didn’t attend the 100th season announcement, and hired a public relations firm to bring light to vacancies and salary discrepancies. Despite this, all are proud of what the symphony has achieved.

“It always strikes me that with all the struggles we’ve been through, the fact that we’ve made it this far is extraordinary,” says Gregory Mulligan, one of the symphony’s violinists and co-chair of the players’ committee.

If the symphony hopes to grow and become more harmonious—both on stage and off—a lot lies at the feet of Alsop. Inside her dressing room, where a framed black-and-white photo of Leonard Bernstein sits on a table, she talks of her vision for the Meyerhoff as a cultural epicenter, a destination that feels embracing and open. If money wasn’t an obstacle, she’d love to see a coffee or wine bar or restaurant in the lobby, so people can gather and bridge the gap between the symphony hall and its neighbors—the Maryland Institute College of Art, Station North Arts & Entertainment District, and The Lyric.

“We’re right here, but we’re not connected,” Alsop says. “I’m hoping that within the next decade, this whole area will be completely transformed so it becomes very welcoming to people.”

Like Meecham, she wants to create concerts aimed at younger audiences. And she’d rather take another look at the subscription model—where audience members sign up for a block of concerts throughout the season, choosing a night of the week to attend, or a series that they find interesting. Alsop likes the idea of switching to themes instead, perhaps four or five a season, that would incorporate talks, films, or plays with symphonic works.

Meecham acknowledges that to inspire loyalty, nonprofits such as the symphony will likely have to incorporate new models that don’t require patrons to decide their Saturday- night schedules six months in advance. He mentioned looking at a monthly, direct-debit model, similar to Netflix or Spotify, where members would pay a monthly fee to attend concerts throughout the year.

Alsop and Meecham would also like to increase diversity, which is the hallmark of the BSO’s outreach. Alsop says she wants to see OrchKids, which aims to not just alter children’s lives but change the diversity of musicians from the ground up, reach 10,000 kids as opposed to 800. African-Americans had a separate orchestra in Baltimore for years, before the first African-American member joined the BSO in 1965. The city still has a predominantly African-American and Latino orchestra, Soulful Symphony, which was founded in 2000.

“I would like the symphony to better reflect the community in which we live—[from] the musicians on the stage, [to] the audience and the people we serve,” Meecham says. “I think there’s a lot more work that needs to be done there, being of cultural relevance to everyone in this city.”

As the flow of revenue from fundraising and ticket sales remains inconsistent, this search for relevance is one every arts organization is facing, says Tom Hall, music director of the 50-year-old Baltimore Choral Arts Society, and the culture editor for Maryland Morning with Sheilah Kast on WYPR.

“There’s an arts audience that’s very loyal, in the know, and able to cross disciplines,” he says. “Then, there’s a community that never does that. And the barriers are significant, both financial and cultural.”

Despite predictions of a changing future, symphony musicians believe the orchestra will remain similar to what it is today—and that’s because playing great music is what unites the orchestra, says Mulligan, who has been with the symphony for 30 of the past 35 years.

“This is music that’s not going away, and I don’t think audiences are going to stop wanting to hear it,” he says, then acknowledges after a moment, “I know this sounds kind of stodgy.”

Symphony musicians are highly skilled, and have spent years at conservatories honing their extremely specific craft before entering the competitive—and

difficult—world of classical music. While the works of Bach, Beethoven, and Tchaikovsky are what they know best, they do understand the need for mixing

that repertoire with show tunes, movie scores, even rock songs at times. Mulligan remarks that during a summer performance with a Led Zeppelin tribute band, “I

was tapping my foot.” However, the key is striking the right balance, he says.

Alsop conducts during a dress rehearsal for Candide, which was written by her mentor, Leonard Bernstein.

The musicians have slightly less far-reaching goals for the immediate future—they’d like to have more full-time players, for one. Earlier this spring, the orchestra had 79 full-time members—15 years ago, that number was 98, and their contract calls for at least 83. Recent auditions will bring in another two or three, Mulligan says, but four musicians retired after last season, and another left. Orchestra members have previously cited their salaries as a reason for the departures. Base pay is a little more than $76,000, while it tops $100,000 at orchestras such as the Pittsburgh Symphony.

BSO THROUGH THE YEARS

1916

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra performs for the first time on Feb. 11 to a standing-room-only crowd at The Lyric. It is established as a branch of the

city’s Department of Municipal Music. In the first season, all three concerts are sold out.

1937

Violist Sara Feldman and violinist Vivienne Cohn become the first women to join the BSO. Some members are supportive, but others picket with signs reading,

“Unfair to Men.” The New York Times reports the incident.

1942

The BSO disbands after only one performance following conflicts between the city and the musicians’ union. By that fall, the BSO is incorporated as a

private organization, and gives its first performance as such on Nov. 19.

1965

Wilmer Wise, a trumpet player, becomes the first African-American member of the BSO.

1982

The Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall opens with a concert featuring pianist Leon Fleisher and conducted by Sergiu Comissiona.

1981

The BSO tours Europe for the first time, and becomes the first American orchestra to tour East Germany.

1990

The BSO wins its first Grammy award for a recording of cello concertos by Samuel Barber and Benjamin Britten with soloist Yo-Yo Ma.

2005

The BSO plays its first concert at its second home, the Music Center at Strathmore in Bethesda. The orchestra is the first in the country to have year-round venues in two metropolitan areas.

2007

Marin Alsop conducts her first concerts as the BSO’s 12th music director, and becomes the first woman to head a major American orchestra.

Photos courtesy of the BSO Archives

“It’s a battle,” Mulligan says. “It’s a challenge to replace more quickly than we’re losing people.”

But there are always moments when the real reason for their chosen career path shines through. One of those occurred this past April, two days after rioting swept through the city following the death of Freddie Gray. Lisicky organized a free concert with members of the BSO and Alsop in front of the Meyerhoff to promote peace and healing. A crowd of hundreds, from pre-school students to professionals on their lunch breaks, gathered and listened to the strains of Bach, Beethoven, Handel, and “The Star-Spangled Banner” that carried in the breeze. The concert was so successful they staged another, in West Baltimore, several days later.

Lisa Steltenpohl, the symphony’s principal violist, remembers the bond she felt with the community that day. Collectively, she and her fellow musicians were “using music to express when words failed,” she says, and as the crowd cheered and whistled, she was reminded of why she performs: to watch people enjoy what she loves.

But the reaction Lisicky received from audience members indicated, to him, a bit of a disconnect between the symphony and the community. “People weren’t sure why the symphony was out there,” he says. A few people approached him afterward to congratulate him, asking, “Why are you guys out here, when the Orioles are in Florida?” They seemed curious as to why the symphony would choose to make a statement about community when even the baseball team that is such a symbol of Baltimore would be playing home games out of town.

Lisicky told them, “We’re part of your community, too.”

It’s Friday night, June 12, the opening night of Candide in Baltimore. The door to Alsop’s dressing room remains shut and an assistant keeps watch as she gets ready for the performance and reviews the score, which is littered with Post-its and highlighter markings, indicating stage directions and cuts. She had remarked to another conductor at the first dress rehearsal, “It’s like Sanskrit.” The symphony musicians squeeze past one another to reach their seats, giving each other knowing smiles. This is business as usual for them.

The audience has gathered, and it contains a smattering of young people, though ushers escort a surprising number of others to their seats with walkers and wheelchairs.

The lights dim, and Alsop walks to the stage. There are a few cheers, and she briefly holds her hand to her heart. Audience members love their maestra, and she clearly loves them back. Each time she arrives at the podium and sees the enthusiastic faces in the crowd, she’s reminded of why the city touches her so deeply. “Baltimore is not really a place of elitism,” she says. “It’s a city all about neighborhoods and communities. I think that’s what I like about it so much.”

Then, she lifts her baton, and the audience is swept into a racous, hilarious world, from the whirlwind overture to emotion-laden love songs.

This time, everything goes off without a hitch, and all traces of dress-rehearsal tension are gone. The audience howls at the antics of the singers, and especially loves the orchestra-performer interactions. When Candide reaches for Alsop’s baton to kill his enemy, she hands it to him, and when he gives it back, she shrugs, wipes it on her jacket and cues the orchestra, amid continued laughter and applause.

The music is sumptuous, and all the instruments, even the triangle, seem to be having an “on” night. The Sun raves, “the BSO’s terrific version of Leonard Bernstein’s Candide led by Marin Alsop and featuring a whole lot of talent packed onstage is among the most satisfying BSO ventures of any recent season.” The Washington Post calls it, “A welcome tradition of light, wonderful ending fare.”

When Alsop lowers her baton at the end, people leap to their feet. The cheers last for minutes, through numerous curtain calls and bows.

After a performance of such musicality and audience appreciation, the future appears bright and limitless, and struggles do not seem insurmountable. And on this night, at least, it feels quite possible that what Alsop says is right: “We’ve been able to make the BSO a world-class orchestra. But also an orchestra of the people.”