No one needs a reminder that gun violence in Baltimore has been at epidemic levels for decades. The homicide rate, which quadrupled the national average some 40 years ago, has only spiraled from there—spiking in the 1990s, and again 2015—and remains at or near the highest rate in the U.S. ever since. And none of the crime reduction initiatives, not the so-called War on Drugs, not former Mayor Martin O’Malley’s mass incarceration policies, and not even the greatest per capita police spending in the country, managed to yield lasting results. In fact, the case can be made those policies and practices did more harm than good.

Gun violence—and policing following the death of George Floyd—was front and center during the 2020 Democratic mayoral primary, which featured incumbent Jack Young, former Mayor Sheila Dixon, former police spokesman T.J. Smith, former prosecutor Thiru Vignarajah, former Obama Administration official Mary Miller, and the then-youngest City Council president in Baltimore history, Brandon Scott. With a late surge, likely sparked in part by the police killing of Floyd just weeks before the primary, Scott, who pledged alternative approaches to gun violence, emerged with a two-point victory.

The high stakes of that election, which played out over days of post-election ballot counting, was the documentary that Baltimore filmmaker Gabriel Goodenough thought he was making.

Eventually, he realized that the bigger story was Scott’s commitment to initiatives like Safe Streets, the violence interruption program that deploys ex-offenders to quash neighborhood beefs, and his Group Violence Reduction Strategy, which directs resources to individuals most at risk of involvement in gun violence. Could they make an impact?

That question quickly evolved. The central tension that emerged during the course of filming was whether the young mayor’s plans would even be given the chance to succeed. The Safe Streets program and the Group Violence Reduction Strategy require not just city, but state and federal support. Meanwhile, the demand for results, as the film documents, is immediate—from local officials, the media, and the distressed citizenry (“the body politic”). Nor did it help that then-Governor Larry Hogan, while publicly decrying violence in the city, did not meet with Scott until six months after his primary victory.

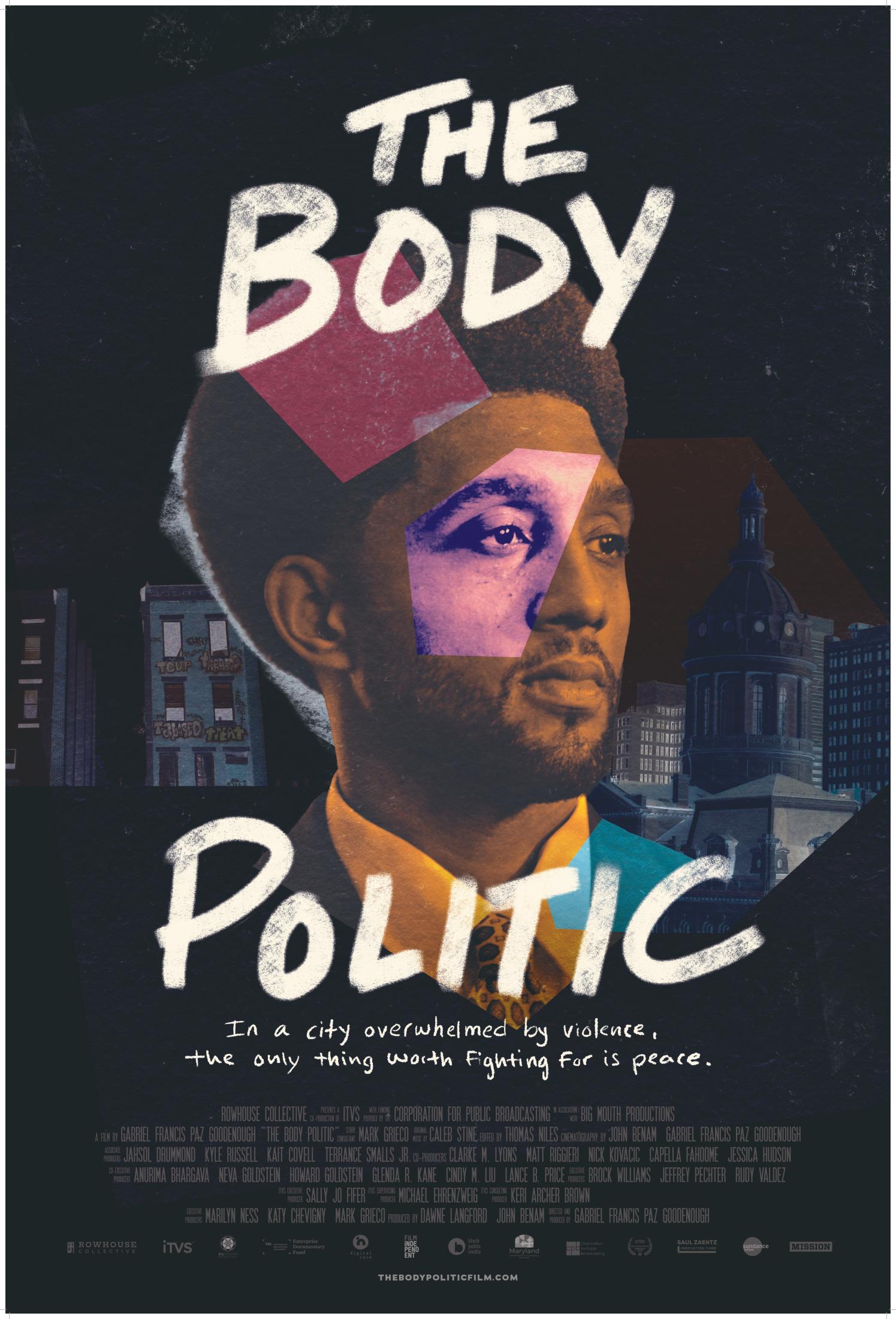

Scott may have become Goodenough’s protagonist by default after squeaking out the 2020 primary, but it is his steadfastness in pursuing a public health approach to gun violence that becomes the subject of the documentary, The Body Politic (90 minutes), which screens at the New/Next Film Fest at the Charles Theatre on Sunday, Aug. 20 at 1 p.m.

One need only to look at the election of New York City Mayor Eric Adams, a former police officer and “tough on crime” hardliner, and watch the local FOX45News to see the political risks involved. We see Scott as a child, in his uncle’s garage working on a car, speaking with aggrieved members of the community as mayor, and huddling with the closest members of his team—notably Shantay Jackson, until recently the director of Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement, and Erricka Bridgeford, the founder of the Baltimore Peace Movement. Both are lifelong Baltimoreans, all too familiar with the city’s gun violence and related trauma, and compelling figures in their own right. They also share the mayor’s dedication to violence intervention programs.

Scott comes across as a committed civil servant, but The Body Politic is not intended to be intimate character study. As anyone who follows city politics knows, he largely keeps his personal life and emotions under wraps. (When he recently announced that his partner was pregnant, it was the first time many of us found out he even had a girlfriend). The subject is really the new mayor’s gun violence prevention initiatives and whether there’s enough patience and political will in the city to apply a long-term, holistic remedy to the deadly epidemic.

If political opponents view the documentary as a potential boon for Scott’s reelection, it’s because in his third year in office, as the film notes in its epilogue, homicides are suddenly down 20 percent—and on track to fall below 300 for the first time in nine years.

Ahead of the New/Next screening, we caught up with Goodenough, the film’s director and producer, to discuss his process, the city’s violence prevention strategies, and what he hopes audiences take away from the film.

A bit of a random question to start, but is that the voice of just recently appointed police commissioner Richard Worley in the opening scene, breaking tragic news over the phone to Mayor Scott?

It is. They have a close relationship that goes back to when Brandon was a City Councilman and Worley served as the police commander in his district. He counts on Worley to give it to him straight. Worley [a Pigtown native] is real Baltimore.

Full disclosure, you and I first met while you were filming this documentary. You shot some footage of me interviewing former Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake and former Mayor Kurt Schmoke for a story about corruption in Baltimore, which ultimately is not included in the film. I did not know at the time that you had started this project shortly after you were diagnosed with cancer.

Bone cancer. Chondrosarcoma. It’s very rare. I had surgery in 2019 and had part of my hip removed. I had gone into the ER about something else, which turned out to be fine, but the radiologist saw a spot on my hip and said I should get an MRI. I was eventually told I had 60 percent chance to live 10 years. I also couldn’t do my old job anymore, which was to hold 40-pound cameras.

You began your career as a camera assistant on projects such as A Beautiful Mind, The Sopranos, and The Wire, and have served as director of photography on a number of documentaries, including A Thousand Cuts and Don’t Stop Believin’: Everyman’s Journey, both directed by award-winning Baltimore filmmaker Ramona Diaz. With the cancer diagnosis and surgery, you decided the time had come to make your own film?

That’s basically it. I grew up in Baltimore and lived mostly in Waverly and Sowebo as a kid. I went to public schools. My mom was a nurse at Hopkins and my dad was a carpenter. After my parents divorced, I moved to San Francisco and went to high school there. Then I went to film school at USC and as soon as I finished, I moved back to Baltimore.

I worked as a bike messenger. I applied for a job at Video Americain and didn’t get hired. Eventually, I got work as an intern, then a production assistant on Homicide: Life on the Streets. I’ve spent 25 years watching people make films and I wanted to make this film because I love Baltimore. I learned a shitload about this city in doing this film. Much of it really disturbing, and some of it amazing.

This is no small leap, going from a career behind the camera, to directing and producing. I don’t know that viewers, including myself, ever fully appreciate the challenges in bringing a film to the screen.

My life is this film. That’s all I do. And that’s been tough on some relationships. I’m already $250,000 in debt. I mortgaged my house to make it, so, yeah, this film is pretty much my life.

You started filming in 2019, correct? What was the initial plan?

Yeah, this was three years of work. More than a year and a half of filming and then 15 months of editing. We essentially had two full-length films. One about the primary. We had cameras with Sheila Dixon, Thiru Vignarajah, T.J. Smith, and Brandon Scott on election night. The model for that was Street Fight [about the 2002 Newark mayor’s race, in which now New Jersey Senator Corey Booker defeated incumbent Sharpe James]. Afterward, when he won, we stuck with Brandon, and the second film became about his effort to address gun violence and implement his holistic approach because that felt like the more important story. Especially for the people who live here. But we couldn’t make a three-hour documentary. Oppenheimer could get away with it. We couldn’t. The two films got edited together—we tried flashbacks, and different things—but the film that emerged from more than 700 hours of footage is about Brandon Scott’s first year in office.

COVID was obviously another obstacle.

Shooting policy meetings over Zoom, while very helpful in terms of informing me personally, is super boring to watch on film. Ultimately, following Shantay Jackson into the community as she is doing her oversight work with Safe Streets, and following Erricka Bridgeford as she organizes CeaseFire events and everything else, became very important. Shantay, you can just see, is all business. Erricka is a sha-woman, priestess, healer, mediator, teacher, and activist. There is simply no one like her.

There’s a key phone conversation after a shooting that I hope people don’t miss. It relates to the motive behind the majority of the city’s gun violence. It’s not drugs, the control of corners, or gang-related activity, as commonly portrayed. It’s a personal beef, it’s over a stolen motorbike, a girlfriend getting “disrespected.” There’s retaliation, and it becomes this circular tragedy. This is why the personal, holistic approach of Safe Streets, Roca, and the Group Violence Reduction Strategy can lower the temperature and mitigate beefs, whereas more arrest and more incarceration fail.

That’s the point, right? We know it’s not really the drug trade fueling the violence. And it’s not gang violence. Gangs have never really been that organized in Baltimore. It’s neighborhood beefs. The violence stems from all these other things, and social media can blow it up tenfold. An Instagram post calling someone a “bitch” that gets seen by hundreds of people can a spark a beef.

There’s another poignant moment early on, when newly inaugurated Mayor Scott has the painting of Lord Baltimore, with enslaved child standing next to him, removed from City Hall. Did you know that was going to happen?

I didn’t. It was near the old entrance to City Hall. I thought it was insane that it was still up. But that’s the founding family of this state. Maryland is a Southern state and that history still resonates today.

For people who can’t get to the film, how do you—in a nutshell—explain the Mayor’s Group Violence Reduction Strategy?

The idea is to surround people who have been shot, or shot at—or are considered highly likely to get shot or use a gun—with resources from multiple agencies that can help them change their life. Help them move, if necessary. Get a job, or get back into school, or get into a training program. Get them the counseling they may need. All of it. But it’s a carrot and stick approach. There is a police officer and someone from the prosecutor’s office there, too. They tell the person, him or her, they can choose this option, but if they don’t and they commit a crime, these same people will bring the full weight of the law. It’s not new. Other candidates had similar proposals. It’s been proven to work, but it’s very expensive.

That’s the rub. It’s expensive. We see Scott and Jackson making their case to the City Council and remaining resolute. We see Scott going to Maryland’s federal delegation, and at first, butting heads with former Governor Larry Hogan, looking for funding. The approach also requires patience. Especially, with Gov. Hogan blaming “woke” politics for the gun violence in Baltimore and calling for more police, more arrests, and harsher sentences as the answer.

We tried arresting 100,000 people a year and that didn’t work. City politics are such—and this is one of the big things I learned—that no one works at long-term solutions. Everyone, and everything about the system, demands short-term results.

What do you think the audience will take away about the mayor and about Baltimore?

The first thing I studied in film school was subjectivity and objectivity. I think the truth is personal in some ways, it’s related to who you are as a human being. So, that’s hard to answer. You know, it’s not even about Brandon Scott. Baltimore is just so crazy. Baltimore is insane. I mean, I will say he’s a good, honest guy and a lot of the problems we’ve had with politicians, he doesn’t have. He has different problems maybe, but I think his heart is in the right place. I think he’s trying to do the right thing for the city. But Baltimore itself is Baltimore’s biggest problem. I think that’s what I discovered in making the film.

*This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.