Arts & Culture

The mysterious death, general strangeness, and undeniable genius of a certain macabre poet casts a large shadow over the city’s literary legacy. But Baltimore’s writing tradition is as rich and diverse as the city itself.

Edited by Ron Cassie

Illustrations by Tonwen Jones

B BEHIND LOCKED GLASS DOORS in the central branch of the Enoch Pratt Free Library’s staff-only section sits a bank-style vault. Inside, safely stored for posterity, there’s a letter penned by F. Scott Fitzgerald—who was living in Paris at the time—to H. L. Mencken, thanking the Sage of Baltimore for reading his just-published novel, The Great Gatsby. Mencken’s diaries, at his request, are kept there, too, as well as Mencken’s limited edition copy of James Joyce’s Ulysses. There’s also a handwritten copy of an Enoch Pratt-contest-winning rap by a young Tupac Shakur, plus a CD from “The Eastside Crew,” the group that the rapper formed while he was a student three blocks away at the Baltimore School for the Arts.

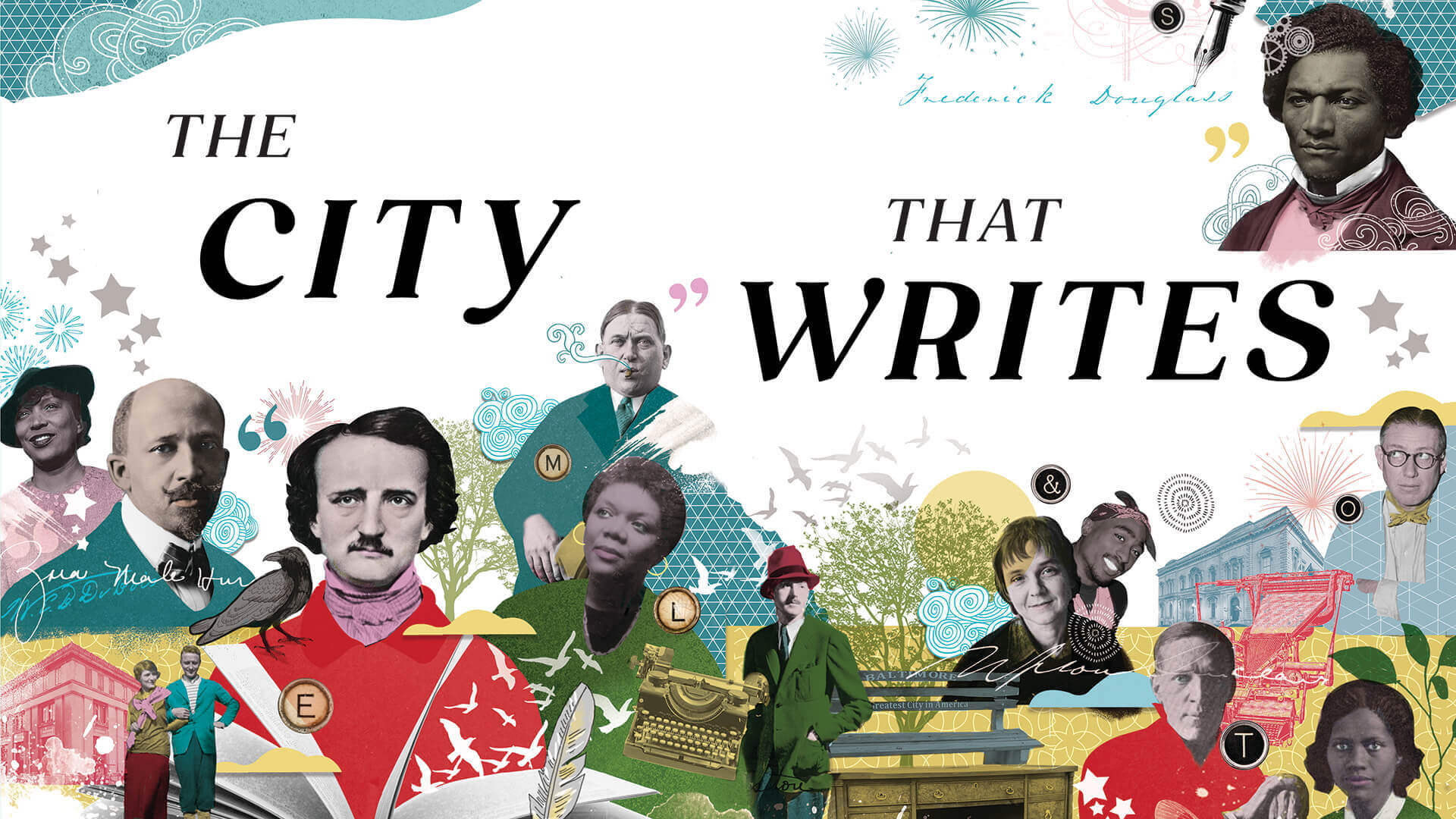

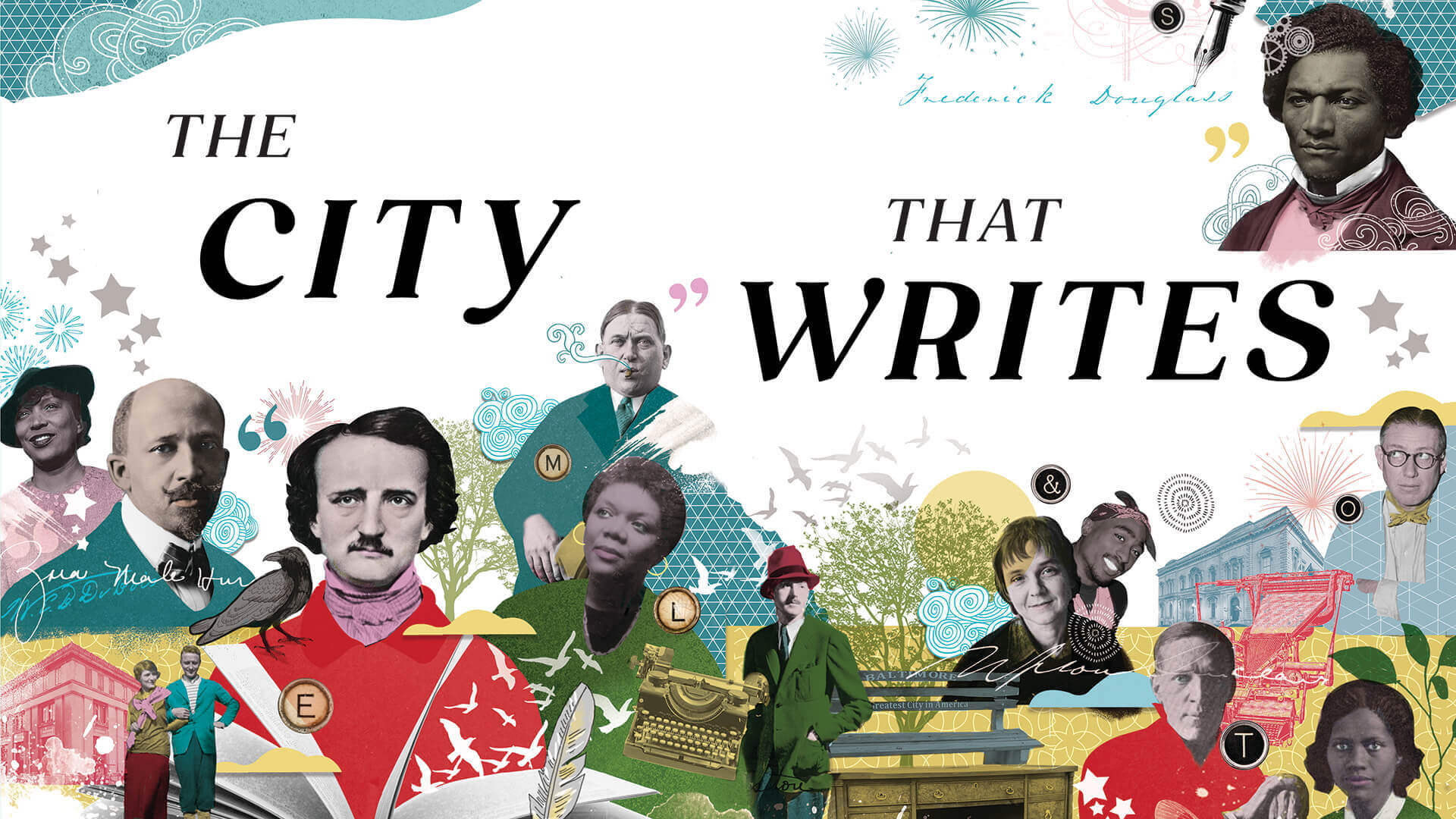

Opening Spread

from Left, Zora Neale Hurston, W.E.B. Du Bois, Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald, H.L. Mencken, Lucille Clifton, Dashiell Hammett, Adrienne Rich, Upton Sinclair, Frances Harper, and Ogden Nash. Sources: Getty Images, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons, New York Public Library.

Most memorably, if that’s the right word, are locks of hair from Edgar Allan Poe and his teenage bride and first cousin Virginia, framed under glass, and a piece of his coffin.

It’s funny how long story ideas can take to germinate. I am pretty sure the seed for this month’s cover story, “The City That Writes,” was planted 11 years ago when I got a behind-the-scenes tour of the Pratt—vault included—for an assignment for this magazine entitled, “Book Smart.”

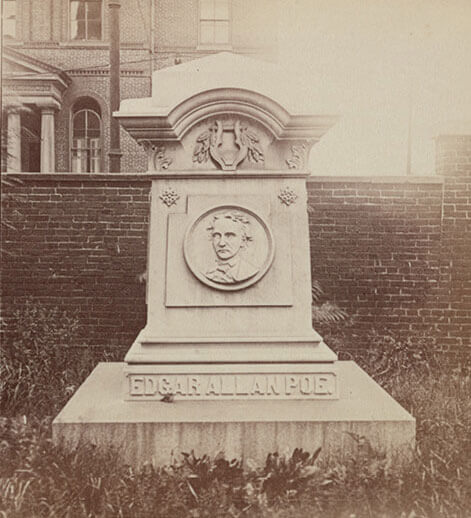

An 1896 photograph of Edgar Allan Poe's tomb. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

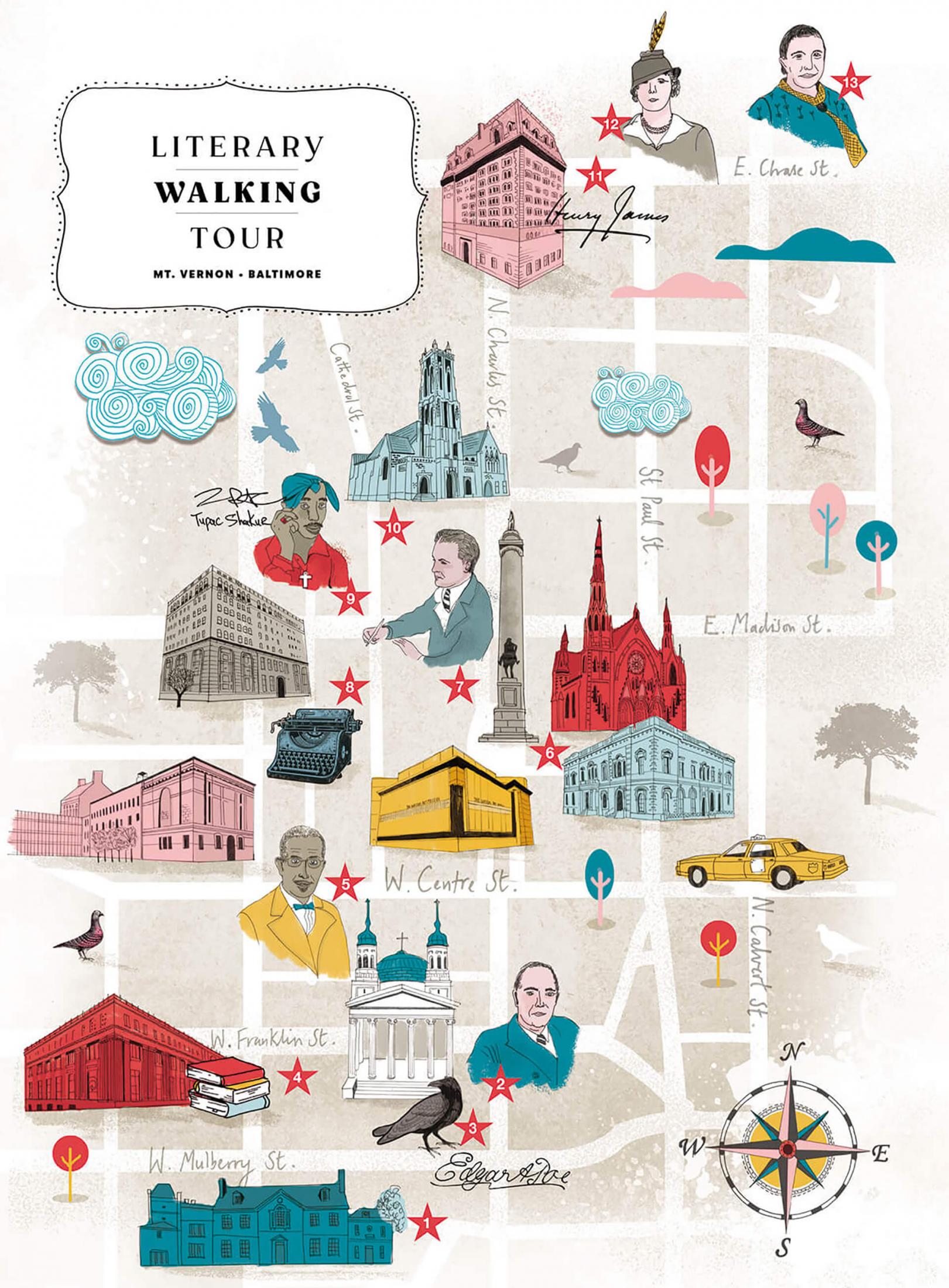

Since that tour, there have been countless other inspirations. A few years ago, I joined a Maryland Humanities Literary Walking Tour of Mount Vernon one weekend morning, and learned not just where Fitzgerald, Upton Sinclair, and Gertrude Stein, among other iconic figures, once lived in Baltimore, but the impact of the city on their work. One often-forgotten example: Fitzgerald’s famous short story about the man who ages in reverse, “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” was set in Civil War-era Baltimore. That walking tour—see our map below—is one of those things generally populated by visitors to the city, but we Baltimoreans could benefit even more from those kinds of tactile trips through the city’s history, architecture, and artifacts. Also worth a visit, for those who haven’t been, are the Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum in West Baltimore, and the recently restored H.L. Mencken home in Union Square. Both are designated National Historic Landmarks. Noteworthy as well: The poet Lucille Clifton’s former Victorian home in Windsor Hills, where she wrote some of her most acclaimed works, is currently being transformed into an education center and writers retreat by her children.

One more not-to-be missed literary experience over the past decade has been the annual January 19 celebrations of Mr. Poe’s birthday at Westminster Hall. One year, I met a woman who had been attending the accompanying late afternoon readings at his burying ground since the 1970s, when she came with her since-deceased husband on their first date. Once the pandemic has relented, hopefully we can return to the annual Baltimore Book Festival and the CityLit Festival, a project of the indispensable CityLit Project, as well.

“BALTIMORE IS WARM BUT PLEASANT . . . I BELONG HERE, WHERE EVERYTHING IS CIVILIZED AND GAY AND ROTTED AND POLITE.”

— F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

In terms of Baltimore’s literary contributions to America, let’s also not forget the Pratt was the first free, inclusive public library in this country, and that the modern printing press, the linotype, was invented here by an obsessive German immigrant named Otto Mergenthaler. All that said, what is most exciting today in The City That Reads—former Mayor Kurt Schmoke’s aspirational nickname from his 1987 inaugural address—is the abundance of Baltimore writers who are living up to the city’s storied literary past. And to be clear, it’s a legacy that doesn’t just begin with Poe, but also Frederick Douglass—whose acclaimed autobiography sold 5,000 copies in just the first few months after its publication—and the poet, novelist, and abolitionist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who was one of the first Black women in this country to be published. In recent years, work from Baltimore writers Laura Lippman, Anne Tyler, Taylor Branch, Dan Fesperman, Danielle Evans, Martha Jones, and D. Watkins—and Baltimore-born writer Ta-Nehisi Coates and playwright Anna Deavere Smith—to name a few, has garnered national praise.

We’re also fortunate in Baltimore that our libraries and bookstores—the number seems to be growing despite the pandemic—continue to bring the finest writers from around the country to the city. (The MFA writing programs at Johns Hopkins, Goucher College, and the University of Baltimore do, too.) And, of course, the Pratt library and the city’s bookstores provide a platform for local authors, who, like the Baltimore writers of the past, inevitably are influenced by, and influence, the city’s sense of itself.

The Enoch Pratt Free Library on Cathedral Street. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

“I wasn’t exposed to writers as a kid growing up in Baltimore, going to school here,” says Watkins, whose new memoir, Black Boy Smile, is due out in May. “But I was exposed to storytelling. That’s what you do in Baltimore. Old guys making up stories on the porch. On the stoop. Rolling up to the corner with a story. Guys telling each other lies, and making stuff up. I didn’t know coming up that being a writer was a job. I didn’t start writing until I was 30, 31, but I was on the street doing those same things and, in that sense, becoming a storyteller and a writer all along.”

To say Baltimore is a place with a unique character, and unique characters, literary and otherwise, could go without saying. But who can resist quoting John Waters? “I would never want to live anywhere but Baltimore,” the renowned filmmaker and writer, whose stories have helped define the city, once said. “You can look far and wide, but you’ll never discover a stranger city with such extreme style. It’s as if every eccentric in the South decided to move north, ran out of gas in Baltimore, and decided to stay.”

Whether Baltimore has served as particularly fertile ground, or has produced an outsized number of writers relative to its size, is difficult to say. What is undeniable, however, is that Baltimore itself is the literary bond between an incredibly rich and diverse group of writers.

A portrait of Baltimore-born poet, author, abolitionist, and suffragist Mary Ellen Francis Harper. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

“Baltimore is the connective tissue, culturally and socially [between these writers],” says Paul Coates, the founder of Black American Press, and father of National Book Award winner Ta-Nehisi Coates. “The same way it was for Red Foxx [who launched his stand-up comic career here] and Billie Holiday. Baltimore has always had a strong cultural presence. Frederick Douglass, who learned to read and write in Baltimore, never forgot Baltimore. In the same way, Ta-Nehisi’s development as a writer can’t be separated from Baltimore. That’s the context from where they start. Baltimore has shaped these writers, and I think it’s fair to say these writers have shaped Baltimore.”

It’s with this “connective tissue” in mind that we asked 13 of Baltimore’s current literary standouts to write something brief about 13 of Baltimore’s past literary stars. It’s our hope that readers will seek out the work of both the Baltimore writers past and present included below.

by Ron Cassie

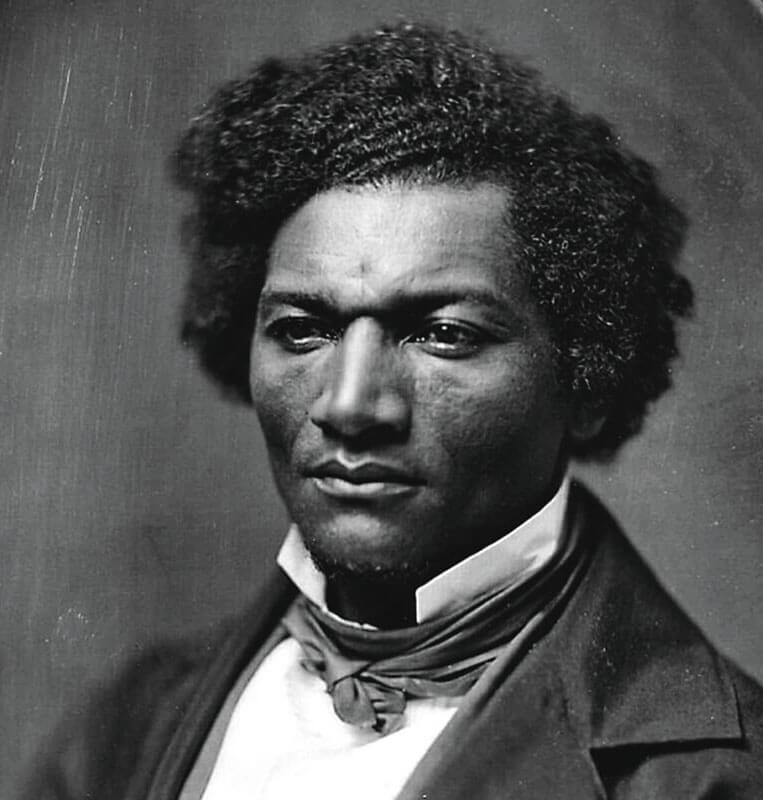

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

By Lawrence Jackson

Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Frederick Douglass, born in Talbot County, was fond of his adopted home city, Baltimore. He left by train in 1838 and could only return in the midst of the Civil War, after the outlawing of slavery in Maryland in 1864. On the evening of his return, he spoke at the Bethel AME Church and said, “My life has been distinguished by two important events, dated about 26 years apart. One was my running away from Maryland, and the other is my returning to Maryland.” Baltimore during Douglass’ time was an anomaly, the place where he witnessed the coffles of enslaved people marching in chains to the wharf for sale “down the river,” but where he also wrote that even as a slave, he was “almost a freeman.” In part, this curious freedom stemmed from the models of liberty that the young Douglass could see firsthand as he learned to read and then, starting with graffiti on the rough-hewn fences of Fells Point, write. His lessons from Sophia Auld, a white woman who shared the alphabet with him, and the anthology called the Columbian Orator he bought at his neighborhood bookshop, are the best-known stories of his early, self-taught career. But there is a less well-known influence shaping Douglass, the writer of three autobiographies, the editor of an important newspaper, the author of revolutionary fiction, and the public speaker who ranks alongside Abraham Lincoln and Daniel Webster as the 19th century’s most gifted orators.

“GIVE US THE FACTS. WE WILL TAKE CARE OF THE PHILOSOPHY...'TIS NOT BEST THAT YOU SEEM TOO LEARNED.”

The skills in writing and debating were developed in the shadows of “Sabbath school exhibitions of the free negroes, which he attended by stealth, and where he was beginning to shine as an orator,” as one biographer put it. His main church was a Methodist sanctuary on Strawberry Alley (modern-day Dallas Street) known as “Bethel on the Point.” At the Strawberry Alley church and on the playgrounds he met other boys and “entered...the art of writing.” In My Bondage and My Freedom, his second autobiography, Douglass signaled his break with white writers and abolitionists of the period who had condescendingly told him “Give us the facts...we will take care of the philosophy...'tis not best that you seem too learned.” Nonetheless, learned he and other local slaves who studied in secret were. Out from some 18,000 free Black and enslaved Baltimoreans of the 1830s came the century’s most prolific and impactful Black female and male writers: Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and Frederick Douglass.

Lawrence Jackson’s works include Chester B. Himes: A Biography and Ralph Ellison: Emergence of Genius, 1913-1952, and a memoir on family history, My Father’s Name: A Black Virginia Family after the Civil War. He is a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of English and History at Johns Hopkins University and founder of the Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts. His next book, Shelter, will be published this spring.

EDGAR ALLAN POE

By Laura Lippman

Edgar Allan Poe casts a long shadow over anyone who writes detective fiction; there’s a reason that the highest honor in the field is named for him. Fittingly, his death in Baltimore also has provided a sturdy mystery—really, multiple mysteries. Why was he in Baltimore on that October day in 1849? What was the actual cause of death? And what was the story behind the Poe Toaster, the unknown visitor to Poe’s original gravesite, who left a bottle of cognac and three red roses there on Poe’s birthday? That tradition, which began in the late 1940s, ended in 2009, but was resurrected by the Maryland Historical Society in 2016.

In 1999, having decided I wanted to write a book about the murder of a “Faux Toaster”—a copycat visitor to the site—I convinced curator emeritus of Baltimore’s Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum Jeff Jerome to let me join the watch party at Westminster. In my memory, I was one of the first to spot a tall, shadowy figure moving toward the grave. Although I was covering the visit for my employer at the time, The Baltimore Sun, I had agreed to be obscure about certain details of what I saw that night, in order to ensure that future visits not be disturbed by those who would unmask the Toaster. I still feel honor-bound not to describe everything I saw.

But the reason that I feel close to Poe isn’t because of genre or Baltimoreor even the fact that I saw the Poe Toaster. I always keep in mind that Poe yearned to make a living from his writing, a difficult proposition then and now.

Laura Lippman is a former Baltimore Sun reporter, a New York Times bestselling author, and creator of the award-winning, reporter-turned-private investigator Tess Monaghan novels. Her latest stand-alone novel, Dream Girl, published this summer to rave reviews.

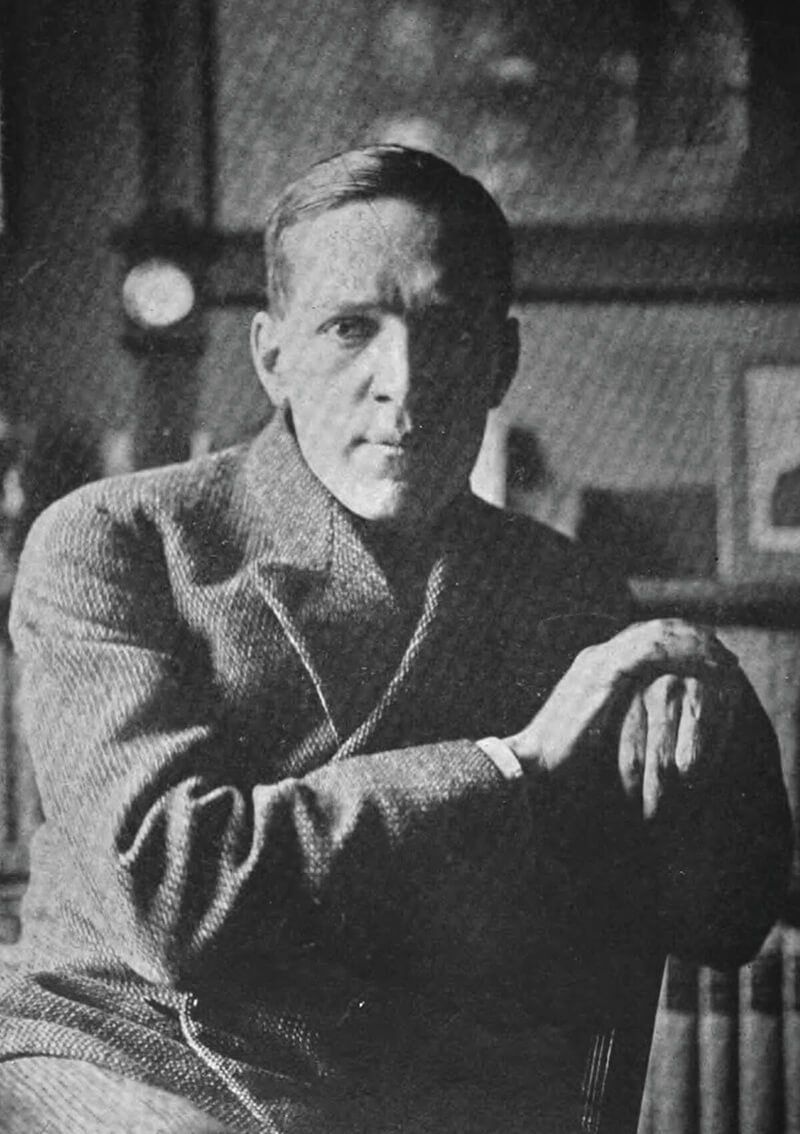

H.L. MENCKEN

By Michael Downs

What are we to do with Mencken? Admire the acrobatic vocabulary, of course, the caustic wit, the heroic—even epic—body of work. But then one must confront the ego, the snobbery that presents as high standards, the misanthropy. We’re still recovering some 30 years on from the posthumous publication of his diaries, which revealed him to be Homo Deplorabus.

“PURITANISM—THE HAUNTING FEAR THAT SOMEONE, SOMEWHERE, MAY BE HAPPY.”

Our mistake is to think of him as an icon. Which we do. Consider his sobriquet: the Sage of Baltimore. How hoitytoity! Another reason is that we find his aphorisms everywhere, as if he were Abe Lincoln. Bombastic, brief, and provocative, Mencken’s one-liners provide top-grade fertilizer for memes and tweets. We know him by his proclamation about puritanism. “Puritanism—the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.” Or the other about American democracy reaching its pinnacle when a moron becomes president. His line about journalism being the “life of kings” graced the wall of the old Baltimore Sun lobby as if writ by the hand of God.

But smash that Mencken statue you have in your imagining. See him not as icon but as iconoclast. Remember that when he wrote, he came at readers with lighter fluid and the match with which he fired his cigar, and he sought to inflame. That’s how he won what might have been the largest readership in America, pre-World War II. He pissed people off. But given that he argued everything, he may not have subscribed to everything he argued. It’s a theory that frees us to read Mencken beyond aphorisms—in essays such as the “Criticism of Criticism of Criticism” or “Newspaper Morals”—and to expect he could be wrong as often as right. Thus, he becomes even more worth our attention. One hundred years since Mencken’s best work challenged readers, he’ll still elevate our thinking, if not by enlightening us then by infuriating us, so that we argue with him even as he entertains.

Michael Downs is a former newspaper journalist and now tenured creative writing professor at Towson University. He is the author of the 2018 novel, The Strange and True Tale of Horace Wells, Surgeon Dentist, and House of Good Hope: A Promise for a Broken City, which won the 2007 River Teeth Prize for literary nonfiction. A Fulbright scholar, he is currently on sabbatical in Kraków studying Polish legends—the number of which he says is legion—in order to turn several of them into contemporary short stories.

ADRIENNE RICH

By Jen Michalski

“I came to explore the wreck,” explains a scuba diver in the titular poem of Adrienne Rich’s Diving Into the Wreck. But she isn’t your typical diver—“not like Cousteau,” and, instead of treasure, she has come to see “the damage that was done” to women throughout history, as well as herself. It’s a poem, groundbreakingly feminist and introspective, that’s inspired my own work (even making an appearance in my latest novel, You’ll Be Fine).

What writers aren’t exploring below the surface of things, seeing the damage done? For Rich, who attended Roland Park Country School, her rise to becoming one of the most influential poets of the 20th century began as a senior at Radcliffe College, when her first collection, A Change of World (1951), was selected by W. H. Auden for the Yale Series of Younger Poets Award. Twenty years and seven collections later, in 1974, Diving into the Wreck won the National Book Award for Poetry. The country, in the midst of the Vietnam War and the civil and women’s rights movements, was experiencing seismic changes, but Rich, whose father had been chairman of pathology at The Johns Hopkins Medical School and her mother, a concert pianist and composer, had understood the bending arc of history much sooner. As Rich writes in the poem “A Clock in the Square” (from A Change of World): “Time may be silenced but will not be stilled/Nor we absolved by any one’s withdrawing/From all the restless ways we must be going.”

Jen Michalski’s writing and short stories have appeared in more than 100 publications, including The Washington Post, Poets & Writers, Barrelhouse, and Gargoyle. She is the founding editor of the weekly literary journal jmww and her award-winning debut novel, The Tide King, was published in 2013. Her latest novel, You’ll Be Fine, was published this year and her collection of stories, The Company of Strangers, is due to be published in 2022.

UPTON SINCLAIR

By Baynard Woods

“SINCLAIR SAW CLEARLY THAT ALL JOURNALISM WAS ACTIVIST IN SOME WAY OR ANOTHER.”

Once, a former Sun reporter who had lived in Baltimore all of three years before moving on to more lucrative pastures, attempted to insult me as a reporter by applying the word “activist” to my work, as if it was a fatal blow in our argument, proving once and for all that what I did was not journalism. Over the years, other disgruntled scribes hoping to cast a long shadow in the setting Sun have hurled the same epithet across the ether and each time, I smile and think of Upton Sinclair, to whom the term “muckraker” was applied, often with similar derision.

Sinclair’s activist journalism is best-known in the form of his 1906 Progressive-era meat-plant exposé, The Jungle. But throughout his long career, Sinclair saw clearly that all journalism was activist in some way or another and that strictly proscribed “objectivity” served the ruling class by making their views seem neutral and universal. He wrote about the unfair trial of anarchist immigrants Sacco and Vanzetti and about the rise of the Nazis. He wrote about incipient fascists and how to cover unjust legal tactics, à la the reliance of holding those charged with crimes without bail—issues, of course, that writers continue to disagree about in this city and around the country.

Sinclair attributed his social conscience and activist writing to his early life in Baltimore, where his parents lived in poverty on the 400 block of N. Charles St. and his grandparents lived much more lavishly at 2010 Maryland Ave. As inequality in the city has dramatically increased in the last century, Baltimore needs more socialist writers like Upton Sinclair—but, in a cruel joke of history, we’re left with the Sinclair Broadcast Group, the locally owned rightwing media empire.

Baynard Woods is a writer and “activist journalist.” His work has appeared in a wide variety of publications, including The Guardian, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Oxford American Magazine. He is the co-author of I Got a Monster: The Rise and Fall of America’s Most Corrupt Police Squad and the author of Inheritance: A Memoir of My Whiteness, which will be published this summer.

Check the Maryland Humanities website for information on its Literary Walking Tours, which were canceled in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but are expected to begin again this spring.

KEY

1. Carl Sandburg: 1878-1967

Old St. Paul’s Rectory, 25 W. Saratoga St. Sandburg was a frequent guest here.

2. Upton Sinclair: 1878-1968

417 N. Charles Street The location of the boardinghouse where Sinclair was born.

3. Edgar Allan Poe: 1809-1849

11 W. Mulberry Street Here Poe visited J.H.B. Latrobe, who selected Poe’s “Ms. in a Bottle” for a Baltimore Saturday Visitor contest, launching his career.

4. Karl Shapiro: 1913-2000

Enoch Pratt Free Library, 400 Cathedral Street Shapiro attended Enoch Pratt Free Library School before WWII.

5. John Murphy: 1840-1922

Eutaw and Centre Streets Historic home of the Afro-American.

6. John Dos Passos: 1896-1970

George Peabody Library, 17 E. Mount Vernon Place Dos Passos wrote many of his works at a carrel in this library’s reading room.

7. F. Scott Fitzgerald: 1896-1940

The Stafford Hotel, 718 Washington Place Fitzgerald lived here while his wife Zelda was undergoing treatment at Sheppard Pratt.

8. H.L. Mencken: 1880-1956

704 Cathedral Street, now part of Baltimore School for the Arts Mencken lived in an apartment here during his brief marriage to Sara Haardt.

9. Tupac Shakur: 1971-1996

Baltimore School for the Arts, corner of Madison and Cathedral Streets Shakur attended the school for a short time.

10. Edna St. Vincent Millay: 1892-1950

Emmanuel Episcopal Church, 811 Cathedral Street Millay frequently read her poetry here.

11. Henry James: 1843-1916

Belvedere Hotel, 1 E. Chase Street James stayed here in 1905.

12. Emily Post: 1873-1960

14 E. Chase Street Post was born in this house.

13. Gertrude Stein: 1874-1946

215 E. Biddle Street Stein lived here while attending nearby Johns Hopkins Medical School.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

By Madison Smartt Bell

For a long time, the only Fitzgerald fiction I liked was the story “Babylon Revisited,” which seemed to me more honest and less overreaching than the two novels I had read. As a freshman at Princeton, I tried This Side of Paradise and found it sentimental in the worst puerile way. I’d read The Great Gatsby once in my middle teens because my parents had a copy, and again when it was taught to us in a senior high school course. No sale: Scott’s longing to belong did not grab me. In college, I wrote a negative review of Gatsby as a paper for an English course, concluding that the soulful Jay was really no more than a retired gangster covetous of his neighbor’s wife. I’m now fairly astonished to see what a young fogey I was then.

So, when asked to give a keynote speech for a Baltimore Fitzgerald Conference, I tried to beg off, unsuccessfully. On the hook for this gig, I thought I would learn and talk about the Fitzgeralds' time in Baltimore, which turns out to be a fairly straightforward tragedy (alcoholism, financial troubles, professional struggles). As the tragic heroine, Zelda pretty well steals the show, though Scott remains a contender.

Fitzgerald redirected the dark energies of that domestic drama, which was also a bitter professional competition, in Tender Is the Night, a novel written during his nearly five-year sojourn in our fair city, one in which his alter ego is reasonably honest about the ways he’s dishonest with himself. For my money, Tender Is the Night is Fitzgerald’s best work, and enough to make me get what all the fuss was about. Though maybe I should try the others again; they say you never read the same book twice.

Madison Smartt Bell is the author of 12 novels, including Waiting for the End of the World, Straight Cut, The Year of Silence, Soldier’s Joy, Save Me, Joe Louis, Ten Indians, Master of the Crossroads, and The Stone that the Builder Refused. His most recent novel is Behind the Moon. He is married to the poet Elizabeth Spires and teaches at Goucher College.

Zora Neale Hurston

By Damaris Hill

Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Born on January 7, 1891, Zora Neale Hurston learned to walk shortly before the age of two when a sow came snorting toward her and her snack. Rather than be robbed of her treats and dignity, Toddler Hurston “had come to rectify her reluctance” to walk, and took her first steps. A few years later, she moved with her family from Notasulga, Alabama, to Eatonville, Florida, which was the nation’s first incorporated Black township. There, Schoolgirl Hurston was never indoctrinated into the myth of racial inferiority and white supremacy, and her mama and the community were heroes. In 1916, Hurston came to Baltimore as a wardrobe girl with a traveling Gilbert and Sullivan Theatre troupe and then stayed to attend Morgan Academy, the high school arm of then-Morgan College, graduating in 1918, saying later she’d arrived with “only one dress, a change of underwear and one pair of tan oxfords.”

In Dust Tracks on a Road (1942), Hurston tells readers about her mama’s determination not to “squinch” her spirit too much, for fear that she would turn out to be the type of Black girl who would grow into a “mealy-mouth rag doll by the time [she] got grown.” Thus, Young Miz Hurston’s mouth became a treasure of words that mirrored her wit—each sharp like diamonds. Ask anyone who went with her to Morgan Academy, a place where writers take root—or Howard or Barnard or Columbia, where she also studied—she was a genius laying the tracks on her road. An anthropologist as well as a writer, she was skilled at amathomancy, reading the patterns of dust, dirt, sand, and the ashes of the deceased. This was an act of love.

In Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), Miz Hurston writes, “Love makes your soul crawl out from its hiding place.” A legacy of love and nurturing bears many gifts; imagination might be the greatest of them.

DaMaris B. Hill is the author of Breath Better Spent: Living Black Girlhood (2022), A Bound Woman Is a Dangerous Thing: The Incarceration of African American Women from Harriet Tubman to Sandra Bland (2019), The Fluid Boundaries of Suffrage and Jim Crow: Staking Claims in the American Heartland (2016), and Visible Textures (2015). Similar to her creative process, Hill’s scholarly research is interdisciplinary. Hill is an associate professor of creative writing at the University of Kentucky.

BOOKISH BALTIMORE

A ROUNDUP OF SOME OF BALTIMORE’S BEST BOOKSHOPS

Baltimore Architecture Foundation

100 N. Charles St., Suite P101 The Baltimore Architecture Foundation is home to a small but excellent bookstore specializing in the city’s architectural heritage. By appointment at the moment.

Atomic Books

3620 Falls Rd. All you need to know is that John Waters receives his fan mail through the Hampden bookstore and stops by regularly to pick it up.

Barnes & Noble Johns Hopkins

3330 St. Paul St. The official bookstore for Johns Hopkins University is also open to the general public—with all the coffee, snacks, and amenities you’d expect from the national bookseller.

Bird in Hand Café & Bookstore

11 E. 33rd St. This Charles Village café, with a tea bar and an espresso bar, is the perfect stop for a bite and a book.

The Book Escape

925 S. Charles St. The cozy storefront in Federal Hill has the new titles that you’re looking for and is crammed with thousands of used and unexpected finds.

The Book Thing of Baltimore

3001 Vineyard Lane What's not to love about free books? The beloved Baltimore institution is currently open one day a month, so check their website for upcoming dates.

Busboys and Poets

3224 St. Paul St. Founded in D.C. in 2005, the restaurant, bar, small bookstore, and community gathering place’s name is a homage to Langston Hughes, who worked as a busboy prior to gaining fame as poet.

Charm City Books

782 Washington Blvd. The historic Pigtown bookseller has all the character and charm that you’d hope for from an independent, family-oriented bookshop.

Co_Lab Books

2209 Maryland Ave. Recently re-opened after closing during the pandemic, the bookstore offers an eclectic selection of art, architecture, and design titles.

Greedy Reads

1744 Aliceanna St.| 320 W. 29th St. Opened in Fells Point in 2018, and in Remington in 2019, both shops are curated for readers looking for books from Baltimore writers and national titles.

The Ivy Bookshop

5928 Falls Rd. Long a Baltimore favorite, the Ivy not too long ago moved to a new home, a renovated Mt. Washington house, with one of the best backyards for reading— and readings—in the city.

Normals Book & Records

425 E. 31st St. For more than 30 years, Normals has remained an eclectic and essential wonderland of used books and music.

Protean Books & Records

836 Leadenhall St. A massive warehouse space filled with a curated collection of new and used books, records, movies, video games, nostalgia, and curiosities.

Red Emma’s

1225 Cathedral St. (Moving soon to 3128 Greenmount Ave.) The 17-year-old community coffeehouse, bookstore, event space, and worker cooperative is moving later this year to a big new location in Waverly.

Snug Books

4717 Harford Rd. Snug Books, which opened in November, replaces The Children’s Bookstore, a beloved Northeast Baltimore institution that closed this past summer.

Station North Books

34 E. Lanvale St. Open early afternoons, the fun, quirky, shop is a can’t-miss collection of art, literature, fine binding, and Marylandia artifacts.

Urban Reads

3008 Greenmount Ave. A community bookstore, café, and event space— not far from Waverly’s Saturday farmers' market— dedicated to Black authors and prison authors.

Viva Books

326 N. Charles St. A small downtown storefront with a low-key vibe offering a range of used books, with a specialization in the arts.

Lucille Clifton

By Kondwani Fidel

A letter to Lucille Clifton:

When I read your poem “1994” from The Terrible Stories, I think about Fidel, my little brother, and Davon, his older brother, who I watched die in a house fire when I was 10, and the many other children in Baltimore who haven’t had their fair shot at life. The ones who ask themselves, or whatever God they believe in, during their final breaths, “Have I not been a good child?”

You were a writer-in-residence at Coppin State College, which is now Coppin State University, and it’s where I currently teach English and Creative Writing. You were the poet laureate of Maryland and lived most of your adult life in Baltimore, the city where I was born and raised. You were a poet, like myself.

I love that in your work you honor the dead—you honor the things that shed. Whether it’s feelings for an ex-lover, or the lies that didn’t taste like lies during the time you told them to yourself. I honor the dead, too. I have a stack of obituaries living in my bedroom. Death is something that has been consistent in my life, but still something I could never get used to. Death is strange. But, death is the only thing that vouches for our reality. In your poem “1994” you also wrote:

you have your own story

you know about the fears the tears

the scar of disbelief

When I read this, I think of the many stories that you left us with. The many stories that encourage the rest of us to use our voices.

Kondwani Fidel is the author of The Antiracist, Hummingbirds in the Trenches, and Raw Wounds. He received his MFA in Creative Writing and Publishing Arts from the University of Baltimore. NPR called Fidel “one of the nation’s smartest young Black voices.”

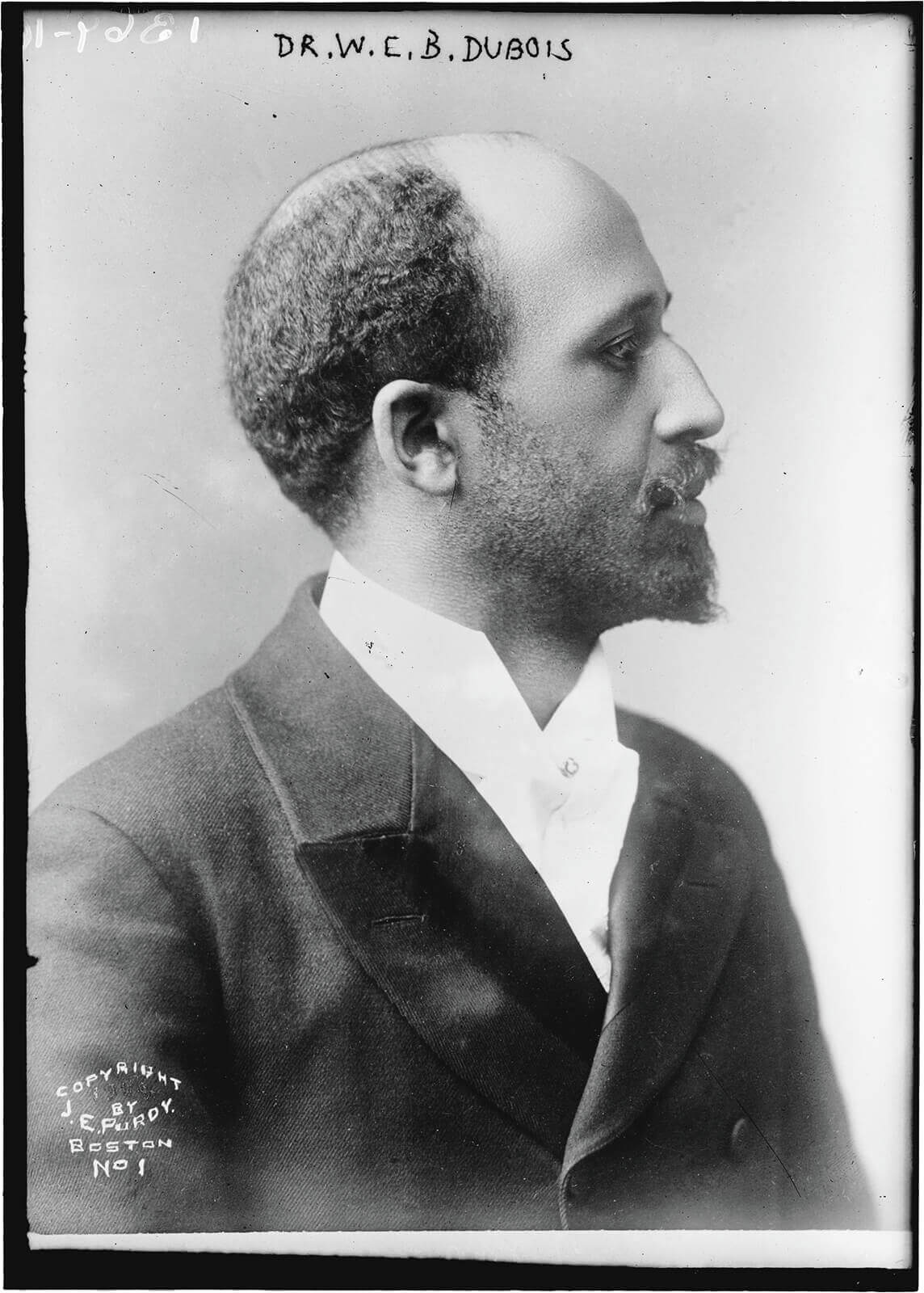

W.E.B. DUBOIS

By Lawrence Brown

Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

In 1903, at the age of 35, Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois penned his classic book, The Souls of Black Folk, to demolish the central tenet of America’s white supremacist theology: that Black people had no souls and were subhuman. Such was the breadth of his groundbreaking career and contributions to American sociology and history, that in 1935, just four years before moving to Baltimore at 71, Du Bois published a staggering 746-page masterpiece entitled Black Reconstruction in America. Here, Du Bois called for the building of an “abolition-democracy” that meant not only the end of chattel slavery, but the “uplift of slaves and their eventual incorporation into the body civil, politic, and social, of the United States.”

“DU BOIS, WHO LIVED IN BALTIMORE UNTIL 1957, MOVED INTO A CITY THAT WAS STILL RIGIDLY SEGREGATED BY RACE.”

Upon moving to Baltimore with his wife, Nina, to be near their daughter, a city school teacher, Du Bois hired renowned Black scholar, activist, and architect C.J. White to design and build his home in 1939 in the Morgan Park community adjacent to what was then known as Morgan College. Du Bois, who lived in Baltimore until 1957, moved into a city that was still rigidly segregated by race. But undoubtedly, he saw the walls of rigid racial segregation begin to crack, too. Morgan College students marched to Annapolis in 1947 to protest inequitable funding for their school. In the early 1950s, more Morgan students began pioneering and waging a sit-in movement to eventually desegregate establishments such as Read’s Drug Stores and Northwood Shopping Center. Du Bois himself was transitioning from domestic politics to international affairs. He had deftly analyzed America’s racial problems and crusaded as an organizer and activist for over 50 years. Firmly in his 70s, he retired from his professorship at Atlanta University in 1944 and resigned a second and final time from the NAACP in 1948. While living in Baltimore, Du Bois remained active and increasingly focused on issues of peace and African independence from European colonizers, writing two books on the topic in 1945 and 1946. After his wife Nina died in 1950, Du Bois later married prolific author and activist Shirley Graham Du Bois. Both remained tireless advocates for racial justice until their deaths in 1963 (W.E.B.) and 1977 (Shirley)

Lawrence T. Brown is an urban Afrofuturist and equity scientist. His first book The Black Butterfly: The Harmful Politics of Race and Space in America was published in 2021. From 2013-2019, he served as an assistant and associate professor at Morgan State University in the School of Community Health and Policy. He is currently a research scientist at Morgan State in the Center for Urban Health Equity.

Gertrude Stein

By Phoebe Stein

Growing up, I heard stories about my father’s “cousin Gertrude” and her love for my family, her sense of humor, deep laugh, and penchant for American popular culture, including one particular tale about her December 1934 visit to Baltimore with life partner/Parisian avant-garde cohort Alice B. Toklas. They stayed with my grandparents at the family farm in Pikesville while my father was home from boarding school. Dad’s central goal over the holiday break was to get his driver’s license, but he forgot to put out his arm to indicate a turn and failed the test. As Dad told it, he returned home from this “tragedy” and stormed into the house, only to see Gertrude with journalists from the Associated Press. She asked my sulking father to bring in my grandparents’ dogs and insisted he pose for the photo with her, too. The result is a family keepsake—a picture of my dad, stonyfaced, with the family dogs, sitting at Gertrude’s feet.

In college, I met a different version of Gertrude Stein, one who rejected America and moved to France.

Gertrude Stein has been both lambasted and lauded for her experimental style, and I cannot say I have read all of her work or enjoyed all the reading I have done. My favorite remains her collection of novellas, Three Lives, set in a port city of “Bridgepoint,” I believe loosely based on Baltimore. (She lived here while attending medical school at Johns Hopkins for three years). In fact, the novella in the collection, “Melanctha,” is a rewriting of Stein’s manuscript for her novel Q.E.D.—considered one of the earliest coming-out stories— about her failed romantic relationship with May Bookstaver in turn-of-the-century Baltimore.

Phoebe Stein has been an advocate for the humanities for more than 20 years. She is the former executive director of Maryland Humanities. She received her Ph.D. and M.A. in English from Loyola University of Chicago and since May 2020 has served as the president of the Federation of State Humanities Councils.

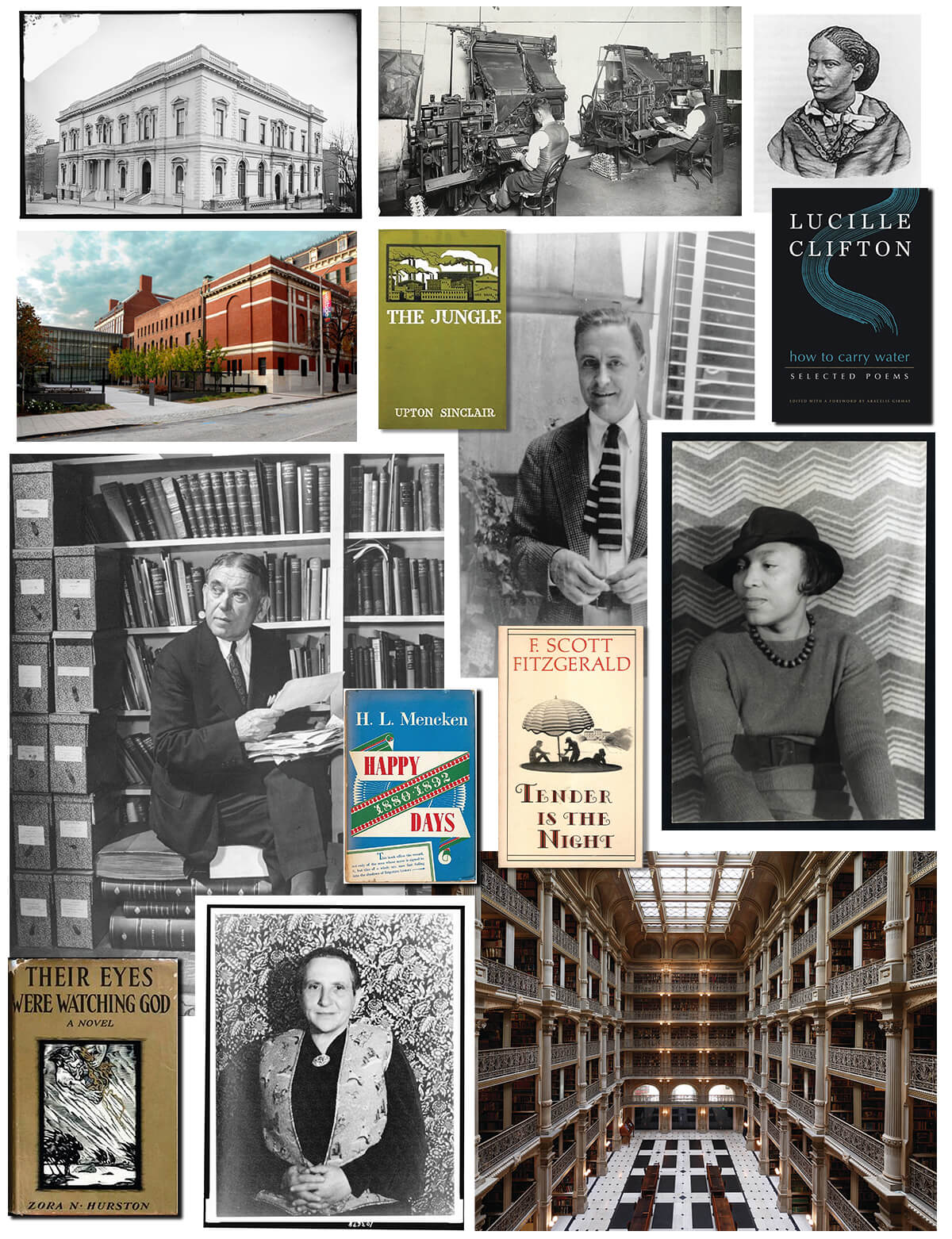

Literary Baltimore

A PHOTO ALBUM OF LITERARY RELICS.

Row 1: The George Peabody

Library; linotype machines;

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Courtesy of LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Row 2: Mencken's Happy

Days; Maryland Center

for History and Culture;

Sinclair's The Jungle; F. Scott

Fitzgerald; Clifton's How

To Carry Water. Courtesy of WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Row 3: H.L.

Mencken; Fitzgerald’s Tender

is the Night; Zora Neale

Hurston. Courtesy of CARL VAN VECHTEN

PHOTOGRAPHS COLLECTION AT THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS.

Row 4: Hurston's

Their Eyes Were Watching

God; Gertrude Stein Courtesy of CARL VAN VECHTEN PHOTOGRAPHS COLLECTION AT THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS;

Peabody Library interior.

Dashiell Hammett

By Dan Fesperman

Before he was ever called Dash, and long before he wrote a single word of hardboiled fiction, Dashiell Hammett was simply Sam from Baltimore, a restless high school dropout who, at age 20, finally found steady employment as a gumshoe for the Pinkertons, working in their downtown office in the Continental Trust Company Building, now known as One Calvert Plaza.

He probably had that building in mind when he later created his first notable detective, the Continental Op, although I’ve never bought into the boosterish local claim that the building’s decorative stone eagles helped inspire The Maltese Falcon. They’re eagles, for chrissakes.

What has always been clear—to this writer, anyway—is that you could never take the Sam from Baltimore out of Hammett’s writing. His prose, like his boyhood city, beguiles by never putting on airs. His dialogue doesn’t speechify or lecture. Hammett gives you only what you need, and keeps you enthralled while doing so.

“BEFORE HE WROTE A SINGLE WORD OF HARD-BOILED FICTION, DASHIELL HAMMETT WAS SIMPLY SAM FROM BALTIMORE.”

His own habits sometimes crept into those of his detectives—first with the Continental Op, then with Sam Spade, and, finally, with the narrator of his last novel, The Thin Man. Nick Charles, like Hammett at that point in his life, was a somewhat idle man of means keeping company with a sharp, sophisticated woman (writer Lillian Hellman, in Hammett’s case). Nick also drank heavily—six tipples in the first nine pages alone, four of them before lunch. By then, so did Hammett, alas.

But even as his life took him to ever more glamorous and exotic locales, we could still see and hear plain old Sam from Baltimore in the stripped-down beauty of his prose.

Like Hammett, Dan Fesperman enjoys writing about dangerous and unseemly people and places, a habit he formed as a foreign correspondent for The Baltimore Sun. Now traveling on his own dime, his novels draw upon those experiences. The sixth of those books, The Prisoner of Guantanamo, won the Dashiell Hammett Prize from the International Association of Crime Writers. His thirteenth, Winter Work, will be published in July by Knopf.

THE CITY THAT READS

Baltimore writers on why books matter.

“I devoured the books because they

were the rays of light peeking out from

the doorframe, and perhaps past that

door there was another world.”

— Ta-Nehisi Coates

“In reading some books we occupy

ourselves chiefly with the thoughts

of the author; in perusing others,

exclusively with our own.”

— Edgar Allan Poe

“I know some who are constantly

drunk on books as other men

are drunk on whiskey.”

— H.L. Mencken

“I read so I can live more than one

life in more than one place.”

— Anne Tyler

“Once you learn to read, you

will be forever free.”

— Frederick Douglass

“Each person has a literature

inside them.”

— Anna Deavere Smith

“I always give books. And I always ask

for books. I think you should reward

people sexually for getting you books.”

— John Waters

John Dos Passos

By Rafael Alvarez

The desk in the Peabody Library where John Dos Passos worked in the last two decades of his life and was often mistaken for a librarian has a small plaque bearing his name: “Novelist and Social Historian, 1896-1970, he spent many hours in research at this desk.”

It was in an alcove high above Mount Vernon that Dos Passos, as he moved from fiction toward history upon settling in Baltimore in 1952, wrote the bulk of a subjective biography titled, The Head and Heart of Thomas Jefferson. I’ve not read the Jefferson book nor sat at the desk where it was written. But I have experienced World War I and the Great Depression through novels the one-time Mount Washington resident published at the beginning of his career. Back then, Dos Passos was mentioned in the same breath as Hemingway and Steinbeck, was featured in the debut issue of Esquire, and, like Hemingway, was a Chicago-born ambulance driver in World War I.

“BOTH [BOOKS] WERE QUITE DUSTY, LIKE THE REPUTATION OF THEIR AUTHOR. WHY HAS HE LANGUISHED?”

In the 1920s and ’30s, Dos Passos drove his stories with characters as familiar as the working-class Baltimoreans who lived on the same block as my Highlandtown grandparents. There were Citizen G.I.’s like Fuselli, an Italian-American grocery clerk featured in Three Soldiers, celebrated as a masterpiece when published in 1921. Fusilli could have been the good-looking kid slicing capicola at the original DiPasquale’s when it opened on Gough Street at the beginning of World War I. Would the neighborhood not have prayed for his soul at Our Lady of Pompei upon news of his death in a trench?

Perhaps I am drawn to Dos Passos because his response to the tumult that accompanied his coming of age as a writer, according to The Guardian, “was to become a novelist with the instincts of a journalist.” I recently bought a vintage copy of Three Soldiers—along with 1919, part two of Dos Passos’ once-celebrated and now rarely discussed trilogy U.S.A.—from Station North Books near Penn Station. Both were quite dusty, like the reputation of their author. Why has he languished? Probably because of his support for conservative causes from about the 1950s on.

A lifelong habitué of libraries, Rafael Alvarez covered the Enoch Pratt Free Library in the 1980s for The Sun. The author of a dozen books, both fiction and non-fiction, all set in Baltimore, Alvarez is currently co-editing an anthology of Baltimore stories due out from Belt Publishing this spring.

Frances Harper

By Martha Jones

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper is best remembered as the African-American suffragist who challenged Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Frederick Douglass in 1866 at New York's National Women’s Rights Convention, insisting that Black women should win voting rights after the Civil War. But that scene—one in which she memorably urged that “we are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity”—occurred only after Harper had established herself one of the era’s most eloquent poets and anti-slavery lecturers.

Born in 1825 in Baltimore City, raised by her uncle—the minister, educator, and founder of Baltimore’s Legal Rights Association, William Watkins—she published her first poem in 1839. By 1850, she escaped the slavery and racism that permeated Baltimore and took a teaching post at Union Seminary in Columbus, Ohio. Harper joined the anti-slavery lecture circuit in 1853, dedicating her talents to the radical extinguishment of human bondage and joining luminaries such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, no easy feat for any woman in mid-19th-century America, no less a Black woman. By the time she faced off with Stanton and Douglass in 1866, Harper was a committed advocate of women’s rights.

Harper married briefly, becoming a widow in 1864, while remaining passionately committed to her literary career throughout her life. Her critically admired novel Iola Leroy, about the plight of slaves and former slaves around the time of the Civil War, was published in 1892 when Harper was just a few years shy of her 70th birthday. Still, her heart’s devotion lay in the future of her only child, a daughter, Mary, who followed in her mother’s path, becoming an accomplished public speaker. Today, the two women are buried together in Delaware County, Pennsylvania. A fitting tribute to this woman of letters and daughter of Baltimore in the city of her birth awaits.