Arts & Culture

Half a Century Ago, The Hippo Became a Haven for the Local LGBTQ Community

Throughout its 43-year lifetime, the Mt. Vernon club was known as a welcoming drag and karaoke spot, a place to come together during the AIDS crisis, and a site to celebrate the advances in gay rights.

It was late, and the next song would have to be the last. As Farrell Maddox cued up the tech-trance “Sandstorm” by Darude, the DJ looked across a churning sea of dancers in the heart of Mt. Vernon, some rocking shirtless on top of the giant speakers, others swaying to the rhythm on the sunken dance floor.

Rainbow disco lights scanned the crowd and a big logo sign hovered behind, its bright pink hippopotamus striking a pose. It was the final night of Baltimore’s iconic Club Hippo—Sept. 26, 2015.

Charles “Chuck” Bowers, the club’s owner of 37 years, watched from the far side of the room. Just before 2 a.m., Maddox caught Bowers’ eye and spoke into the mic. “Chuck doesn’t have a microphone, so he can’t say anything, but if you can see him, and you see the look on his face, you know where his heart is right now.”

As “Sandstorm” wound up toward its explosive climax, Maddox remembered a favorite song that just had to be played. “Can we do one more?” he asked the crowd. Bowers held up one finger. “Get ready with the strobes,” said Maddox, turning to Norm Hillenburg, who was working lights, before slipping a beloved CD into the player.

It had been a long journey to this final party at one of Baltimore’s longest-standing LGBTQ venues. From the night it opened at the corner of Eager and North Charles streets on July 7, 1972, the Hippo was more than a discotheque. It was the beating heart of the local queer community—a welcoming party with beloved drag shows and karaoke, a place to come together during the AIDS crisis, a site to celebrate the advances in gay rights that occurred over the club’s lifetime.

Most of all, it was a safe haven, where patrons could be themselves and get lost in the disco lights until last call at 1:40 a.m., Tuesday through Sunday. And even after it closed for good, that curved building on a Mt. Vernon crossroads remains an important touchstone of Baltimore history.

Long before the Hippo was a dance hub for all walks of city life, its art deco building had many lives. Starting in 1939, 1 West Eager Street had been the home of the Chanticleer Club, hailed as “America’s Finest Supper Club,” where for almost three decades the city’s well-heeled smoked and drank and danced to live acts by everyone from once-local stars like Billie Holiday and Eubie Blake to national headliners like the June Taylor Dancers and Dean Martin.

It was constructed in the late ’30s and designed by local architect John Poe Tyler, a descendant of President John Tyler and famed poet Edgar Allan Poe, whose office at 347 North Charles Street was also located in the heart of Mt. Vernon. Two homes were demolished to make room for his streamlined corner structure with its signature sensual curves.

In the early 1960s, trombonist Lynn Summerall performed with the Mello Men, a 16-piece band of teenage musicians from a variety of Baltimore high schools. “I remember how exciting it was for these high school boys to put on our electric blue tuxedos and go down to the Chanticleer to play,” says Summerall, now 77. “I was on that dance floor under that same art deco ceiling at age 15 or 16, playing big band music. Little would I have thought that 10 years later I’d be traipsing back to the Hippo in search of young men to dance with.”

The supper club closed in 1967, with societal shifts leading to the demise of café society nationwide, and the building remained vacant for the next five years. Then, in early July 1972, Kenny Elbert and Don Endbinder brought 1 West Eager Street back to life as The Hippopotamus, with the opening weekend boasting “The Biggest and Best Gay Bar in the World!”

At the time, Mt. Vernon had already begun to emerge as the city’s “gayborhood,” with Leon’s bar in operation since 1957 and The Drinkery opening the same year as the Hippo. Named for the dancing pink hippos in Disney’s Fantasia, this new gay nightclub spun mostly disco and R&B records for large crowds on its sprawling dance floor four nights a week. Eventually, mirrors were etched with charming cartoons of the namesake animal, and as drinks were ordered, patrons saw themselves reflected amongst them in a swirl of lights.

“You never entered through the front at the corner of Charles and Eager—you entered on the side [through] the Saloon,” recalls Michal Makarovich, a long-time Hippo patron, referring to the elegant back room advertised for “quiet conversation and subtle cruising.” “But if you turned left, you went down a long hallway, the restrooms were on your right, then you went through the doorway, and there was The Palace.”

He’s talking about the main discotheque, which was sunken 18 inches and flanked by two bars. On a balmy summer opening night, “People were dressed to the hilt,” says Makarovich. “They were really flashy and there were lots of women—you know, at some bars, women would get in the way if you were trying to cruise. But it was a really comfortable place for everyone. A lot of straight people went there.”

Bowers first started as a bookkeeper for Elbert in 1976. “When I entered the Hippo, it was a new world for me,” says the Federal Hill native, who grew up attending local Catholic schools before graduating from Southern High School. “I fell in love with the bar, I fell in love with the community. Disco was knocking on the door. And I walked in at the right time.”

Two years later, with Elbert looking to other ventures, Bowers bought the business, and under his lively creative direction, the Hippo—as it was quickly nicknamed by patrons—entered its heyday. Theme nights were added, including a Sunday Tea dance, beginning at three in the afternoon. Friday was Ladies’ Night in the disco, with Gay Bingo in the Saloon on Wednesday. Men’s Night was wildly popular, recalls veteran bartender Danny Noël, who was crowned as “Mr. Gay Baltimore” at the Hippo in 1988. “The line started at the Saloon door and it would go all the way down to Gampy’s,” aka the now-shuttered Great American Melting Pot, a late-night eatery that stayed open well past last call on 904 North Charles.

Noël, a U.S. Army veteran, slung drinks at the Hippo during the ’80s and ’90s. He fondly remembers when Wednesdays were Big Band Night, featuring the Ed Williams Big Band, a holdover act from the Chanticleer days. “I was a doorman, dressed up in a tuxedo with a top hat, and I would open the door for the people coming in—elderly people, [in their] 70s, 80s, and 90s that remembered the Chanticleer,” says Noël, noting that the crowd was both queer and straight, with drag queen Stacy Maxwell running the coat check. “Oh, it was beautiful, and we had all pink linen tablecloths with beautiful chairs and candles on every table. It was like you walked into the 1930s.”

Now in his 60s, he says the Hippo had outsized importance for young gay men in its early years, calling it “the central place” for not just the city of Baltimore but the entire state. “If you were a country boy from Hagerstown or southern Maryland, you knew you made it in your gay life the moment you were able to walk into the front door of the Hippo,” says Noël. “That’s when you knew you were home.”

The Hippo opened just three years after the Stonewall riots in New York City, when a police raid of a beloved LGBTQ bar led to a violent attack on patrons. It was this historic event that sparked the gay rights movement of the 1970s. Queer people were fighting for basic equality in a resistant America, as were people of color in a quest for civil rights. And in the days of lingering racism following Baltimore’s 1968 riot, the Hippo was not only an inclusive space for the white LGBTQ community, but across color lines, too.

“I didn’t know where I would be welcome, because there are divisions in the gay community, where the Black gays may not like the white gays in their clubs, or the white gays may not want the Black gays in their clubs,” says Kevin Brown, owner of Nancy by SNAC in Station North. “But I didn’t feel that going into the Hippo—I thought it was a new era, a new time. And I met my life mate there. We’ve been together for 33 years now.”

Brown reminisces about the club’s massive Halloween parties, as well as regular Saturday nights, which tended to be the busiest. “The lines would be wrapped around the block, because everybody was welcome there all the time,” he says. “And that’s because of its leadership—Chuck Bowers was a hands-on owner. You saw him in the club. You saw him interact with the patrons. He was providing a safe haven for gays in the community, where they could come and be who they are.”

“WALKING INTO THE FRONT DOOR OF THE HIPPO…THAT’S WHEN YOU KNEW YOU WERE HOME. ”

Bowers grew up with an earnest work ethic. His father worked three jobs as a trolley car driver, undertaker, and chemist, and it wouldn’t take long for his son to take on a paternal role for his employees and customers, too. “I wanted them all to realize that it was their home,” he says. “I didn’t care who you were, what you were, what color your skin was, as long as you behaved yourself and had a good time. That’s all I cared about.”

During his 37-year reign, “where everyone is welcome” became the club’s unofficial motto. And DJ Maddox can attest to this. He first went to the Hippo as a patron in 1980, and at the time, “I was kind of that terrified person—I didn’t know what to expect, and I walked in and felt like I had walked into heaven,” he says. “Everything about it—the number of people, the variety of people, the diversity within the room. I was in awe of the music. I thought, I want to be the one playing the music here someday.”

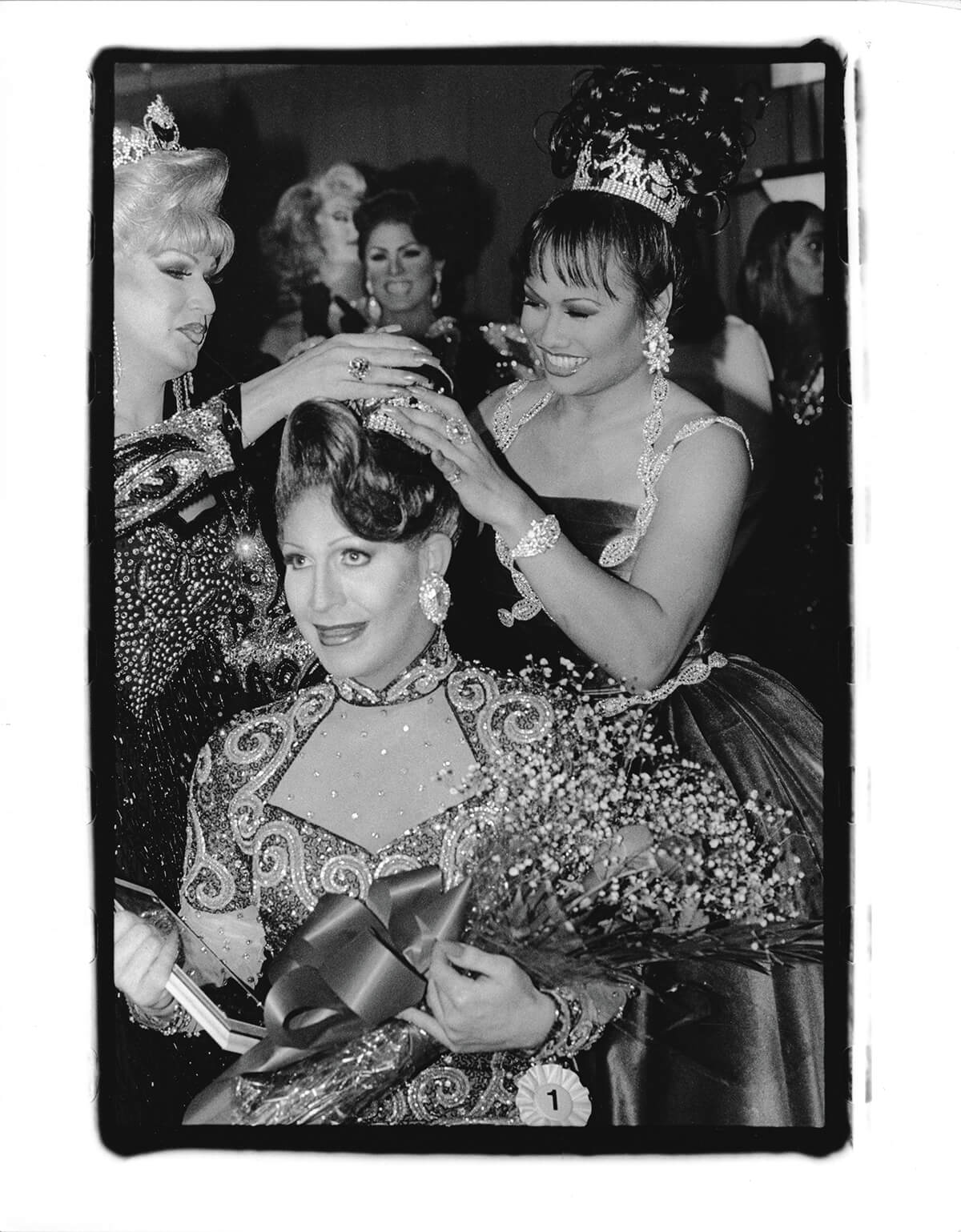

The Hippo hosted both DJs and live performers, including a variety of stars such as The Weather Girls, Wayland Flowers and Madame, Jody Watley, and the Broadway cast of Mamma Mia! And drag shows were always a big draw.

“Baltimore had seen it all and they appreciated drag,” says Jeffery Roberson, who performed at the Hippo many times in the late ’90s and 2000s as drag queen extraordinaire Varla Jean Merman. “And at the time, the biggest drag queen in the world was from Baltimore.”

Hairspray made its cinematic debut in 1988, starring Baltimore’s beloved drag matriarch, Divine, and written and directed by its transgressive filmmaker John Waters. But even amidst their acclaim, a hostile attitude still persisted toward the local LGBTQ community, only increasing as they made strides toward social acceptance. In the preceding years, the city had launched its first-ever Pride Parade and founded its inaugural LGBTQ activism and resource organization, the Baltimore Gay Alliance, both in 1975.

“It was very dangerous for a gay man to hang out in a non-gay bar or club at the time,” says José Villarrubia, a former Hippo patron and resident of Mt. Vernon since 1984. “Gay spaces were the only space where you could act like yourself. But even so, I saw queer bashings right outside of [them]: straight guys coming out of a car and picking a random stranger to beat up.”

And on top of that, another threat was spreading across the country. In the summer of 1981, the first cases were reported of what would come to be known as the AIDS crisis, and on July 3, The New York Times published an article with the ominous headline: “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” That decade, more than 100,000 people would lose their lives.

All the while, the Hippo remained open, offering support to its patrons and hosting fundraisers while trying to maintain some semblance of optimism on the dance floor.

“Things did change with the big ‘A’,” says Bowers. “We were going to funerals quite a bit. We lost a lot of friends—a lot of friends.”

“In those days, it was like a nightmare,” says Lynda Dee, a patron of the Hippo in the 1980s, who co-founded AIDS Action Baltimore with Waters’ collaborator Pat Moran and the late Garey Lambert, projectionist at the Charles Theatre and editor at the now-defunct Baltimore Alternative. “That camaraderie and that family spirit from the clubs really held us all together.”

Over the years that followed, the Hippo continuously adapted to the changing times. At the turn of the 21st century, the club added karaoke in the Saloon’s side lounge and introduced hip-hop nights in the discotheque, providing “the kids who were gay, who really didn’t want to be out, a place they could come out unexamined,” says Brown.

As new milestones were reached—against discrimination, for civil unions, and so on—societal shifts in acceptance played a part in the demise of queer-specific venues. Many point to the internet and the growing popularity of online dating as the death knell for clubs like the Hippo, as well as increased visibility, both on television and all throughout pop culture, offering them more space to be themselves.

Eventually, by 2015, Bowers, disenchanted by the rise in technology and shifting atmosphere of nightclubs, decided to sell the neighborhood’s last true dance floor.

“One thing that older queers like myself miss the most is that secret society,” says Makarovich. “For years, Leon’s didn’t even have a sign—you just knew it was there.”

Today, no hint of the Hippo remains beyond the building itself and the section of North Charles, just south of Eager, that has been designated “Chuck Bowers Way.” When Bowers closed the doors, his iconic disco was transformed into a CVS. The original sign, with its silver hippopotamus, is now on display a few blocks away at the Maryland Center for History and Culture, which also holds a scrapbook that Bowers and Maddox assembled of autographed headshots and other ephemera from the club’s heyday.

The “gayborhood” has changed, too, though a few LGBTQ bars remain. The reimagined Central on North Howard Street. The biker bar Baltimore Eagle on North Charles. The Drinkery on West Read, opened the same year as the Hippo, and Leon’s, now in its 66th year of business.

Every March, Brown and his partner go back to that corner of Eager, to the exact spot outside of the old art deco building where they met 33 years ago. The lights are undoubtedly brighter and the music canned, but they wander the aisles of the chain pharmacy, purchase candy bars, and reminisce about the decades when this location was magic. “He likes Reese’s cups, I like Snickers,” says Brown.

At 78, Bowers still lives in Mt. Vernon and picks up his prescriptions at his former club—out of convenience, not nostalgia—though the energy of the Hippo is forever a part of him. “I used to joke, when that day comes that I’m in a box, make sure my music is with me,” he says. “Because wherever I go, I’m gonna have a party.”

On that final night at the Hippo in 2015, Darude’s “Sandstorm” slid into the last song ever. There was a cymbal crash, and then a slow rumbling: the opening thunder of “It’s Raining Men” by The Weather Girls.

Humidity’s rising

Barometer’s getting low

According to all sources

The street’s the place to go

’Cause tonight for the first time

Strobes flashed like lightning. Maddox was in Heaven—aka Bowers’ nom de plume for the DJ booth.

Just about half-past ten

For the first time in history

It’s gonna start raining men

Hallelujah, it’s raining men, amen

In that moment, Maddox thought of all of those who had danced in the club over the decades. “You couldn’t be in there that night and not feel their presence,” he says, thinking of friends lost to the AIDS crisis, too. “It was like every emotion that had ever been in that room was there at that instant.”

Hillenburg brought the disco ball down slowly from the ceiling and all the hands in the room reached up.