Arts & Culture

Dream Boat

The tragic last voyage of the Pride of Baltimore.

On April 2, 1986, Capt. Armin Elsaesser III was elated. A vivid and fluid writer, Elsaesser now had real cause to let his prose flow. Under his command, the tall ship Pride of Baltimore was returning from a successful tour of Europe, zipping west across the Atlantic, carrying Elsaesser and a crew of 11 toward the Caribbean. The 42-year-old, Ivy League-educated skipper could barely contain his glee in his log. “Now we are flying! As we come off the foamy white crests of sapphire seas Pride lifts her head 4 to 5 feet beyond the waterline. . . . The Power! The Energy! The giddy feeling of soaring through liquid blue space.”

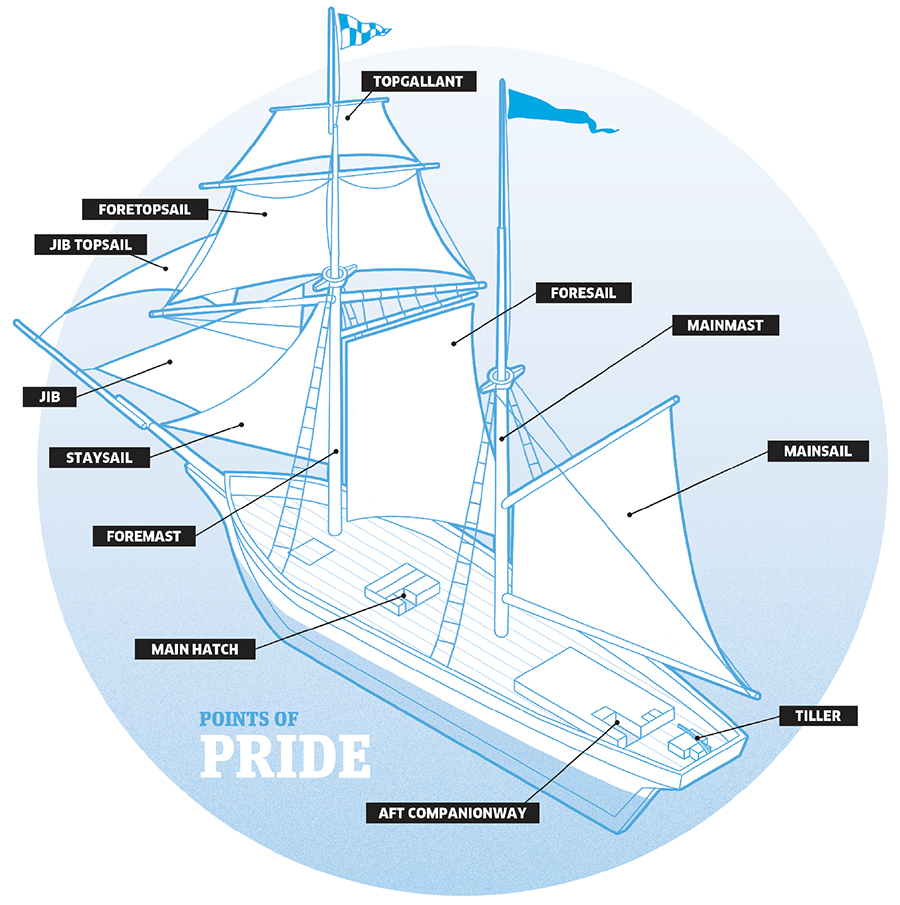

Pride’s immediate destination was Barbados, and eventually, her home port of Baltimore, where she had been built by hand 10 years earlier, part of the rush of urban renewal that yielded the National Aquarium, the Science Center, and Harborplace. That she was globetrotting at all was a surprise. She was built as a historically accurate replica of a Baltimore clipper, a type of topsail schooner prized for speed and agility that had been used to great effect against the British Royal Navy in the War of 1812. Initially, city leaders—including then-Mayor William Donald Schaefer—figured Pride would be a floating dockside attraction, but they reconsidered as she neared completion. The spectacle of constructing her in the Inner Harbor had drawn a lot of positive attention. And around the country, there was renewed interest in historic tall ships. Why not sail her to other ports, where she could drum up goodwill for her home city?

Taking her out on “blue water,” however, required changes. Pride was retrofitted with some modern conveniences, including an engine, a radio, and, naturally, safety gear, such as two self-inflating life rafts. But other features, like the hull’s lack of watertight bulkheads, were not addressed. Also not addressed was the ship’s stability, or relative lack thereof. While the boat was seaworthy, some felt that she didn’t possess the kind of stability needed for the kinds of ocean voyages she would now be taking. As such, it was strongly suggested that the ship not carry the public while under sail, only professional crew.

Pride’s potential shortcomings were taken seriously, says Gail Shawe, the head of the organization that managed the boat for the city.

“We were always concerned that we not put her in harm’s way,” she says. “We knew . . . that she had limitations. . . . But we couldn’t rebuild her. She was what she was.”

After Pride was commissioned on May 1, 1977, her captains quickly realized she was a ship with some quirks, and these quirks earned the boat several nicknames, including the “Wild Black Mare,” the “Flexible Flyer,” and, on occasion, “the bitch.”

“When you’d do a boat check every hour, it wasn’t unusual to walk up to the person you were relieving and say, ‘Well what’s the bitch doing to us now?’” remembers Jennifer Lamb Bolster, a veteran of multiple Pride voyages.

Bolster also happened to be Elsaesser’s girlfriend and was privy to his doubts about the boat, concerns that grew after an experience in the Baltic Sea during the European trip. A strong gust of wind combined with steep seas laid the ship on its side and crew members went overboard. The boat righted itself at the last second and all crew members were recovered safely, but the ordeal, says Bolster, “shook Armin to his core.”

“I felt . . . that I was in an extremely elite fraternity.”

“When we got into Poland or Germany and we were met by Pride staff, Armin said, ‘This ship, when we get back to Baltimore, it needs to be tested. I don’t trust it,’” recalls Bolster.

But for all his worries, Elsaesser could not deny the ship’s magic—and the Atlantic crossing had been a dream. In addition to perfect trade wind conditions, dolphins frolicked alongside the bow and the crew—a mix of Pride veterans, experienced sailors, and eager novices—enjoyed the romance of traditional sailing.

Heading up the veterans was first mate John “Sugar” Flanagan, 27; second mate Joe McGeady, 26, of Severna Park; and boatswain Leslie McNish, 30, a native of California. All three were tight, having sailed together on Pride previously. Plus, Flanagan and McNish were a longtime couple.

Vincent “Vinnie” Lazzaro was new to old-fashioned sailing but had plenty of experience on the water. The 27-year-old commercial fisherman had kept a cool head the year before when the fishing boat he was on sprung a leak and had to be rescued by the Coast Guard.

Then there was 29-year-old ship’s carpenter Barry Duckworth, whose aversion to water did nothing to diminish his love of sailing; 26-year-old aspiring seaman Robert Foster Jr.; 23-year-old Daniel Krachuk; and James “Chez” Chesney, a 25-year-old New Yorker, who was hired as the cook.

Finally, there were three novice deckhands from Baltimore: Linthicum native Scott Jeffrey, 27; Susan “Susie” Huesman, 23; and Nina Schack, also 23, who had grown up in Cedarcroft and attended The Bryn Mawr School.

“I felt, at that time, that I was in an extremely elite fraternity,” says Jeffrey.

However ideal the Atlantic passage had been, by the time the ship reached the Caribbean, this makeshift seafaring family was ready for some R&R.

Privacy was especially welcome for Lazzaro and Schack. For not the first or last time, Pride had facilitated a love connection. Though apparent opposites (Lazzaro was quiet and tall; Schack was vivacious and petite), the two had a lot in common. Both came from artistic and intellectual Italian-American families. In early May, Schack wrote a letter to her mother that contained the line, “Vinnie is a man I could marry.”

A few days after Schack mailed that missive, Pride departed the U.S. Virgin Islands, heading north. On May 14, about 250 miles north of Puerto Rico, trouble struck. By mid-morning, squall lines had gathered off to the east, making Elsaesser uneasy, and he issued a non-emergency “all-hands” call, ordering the crew to prep the boat for possible storms.

“The boat was not overpowered at all. We’d gotten the boat ready for more wind,” remembers Flanagan, who estimates that it was blowing a gale of roughly 35 knots by the time the crew finished the sail changes.

And then the unthinkable happened. A strong gust of wind—maybe as high as 92 miles per hour—hit the ship at an almost 90-degree angle. The gust “slapped” the boat down in the water and she began to flood.

Immediately, it was chaos. Elsaesser called for a head count and crew members began falling into the water. Within two minutes, the sea had swallowed the Pride of Baltimore. The crew began congregating around the ship’s two inflatable life rafts but neither was holding air.

It quickly became apparent that not everyone had made it. Lazzaro was last seen making his way along the upturned side of the ship, heading toward, many speculate, Schack. Elsaesser survived the sinking, but was last seen swimming away from the amassing crew members, though toward what, no one knows.

Schack’s dead body floated by about 10 minutes after Pride went down. The crew agonized over what to do. They could use the yellow foul-weather gear she was wearing, but it felt like a betrayal to take it. Finally, they did, and her body was pushed out to sea.

After a while, Duckworth, the weak swimmer, reappeared, having taken on a lot of seawater. The crew took turns propping him up in the water until he died sometime in the late afternoon.

With night approaching, and despite several cracked ribs, Chesney, the cook, began blowing air into one of the rafts. Miraculously, it began to inflate. An hour later, it was buoyant enough to hold all eight survivors, and they climbed into a life raft built for six. This would be their home for the next four-and-a-half days as they drifted—scared, cold, and dehydrated—through the Atlantic. They knew no one was looking for them yet. Neither of the ship’s emergency homing beacons had been activated, and regular radio communication with the home office—always difficult—had been reduced to a bare minimum before the accident since it was such a headache and they were, as Gail Shawe says, basically “in home waters.”

Finally, on the night of May 19, with McNish standing watch and flashing an S.O.S. signal with a flashlight, a Norwegian tanker spotted them. Once on board, McGeady called his parents in Severna Park, and the news spread.

At press conferences in Puerto Rico and Martin State Airport in Middle River, the media descended.

“Some of it was quite horrifying,” remembers Chesney. “For instance, ‘How did you feel when Barry stopped breathing and sank?’ You know, what kind of question is that?”

The survivors dealt with the sometimes distasteful media coverage by getting on with their lives as best they could. Luckily, there was a happy occasion to bring them all together.

While treading water in the immediate aftermath of Pride’s sinking, McNish had turned to Flanagan and said, “Sugar, I don’t want to die without being proposed to.” Flanagan had responded in typically understated fashion, “Sure, Leslie. If we survive, we’ll get married. Just keep kicking.” True to their words, Flanagan and McNish tied the knot in California that August with all eight survivors in attendance.

Back in Baltimore, however, things were anything but celebratory. Condolence letters poured in from all over the globe. Many urged the city to build a second boat, and unsolicited donations arrived. But officials had other worries as the thorny question of blame hung in the air. Four people were dead and the boat had been lost. Who was responsible?

“This ship . . . it needs to be tested. I don’t trust it.”

Almost immediately, members of the sailing community began second-guessing everything from the ship’s design to Elsaesser’s handling of the crisis.

The Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board opened inquiries, but the findings were complicated.

Essentially, both reports agreed that the ship simply had been overwhelmed by the wind. They rendered no conclusive judgments on her inherent stability. The malfunctioning life rafts were, as best anyone could figure, a terrible fluke. The main criticisms were of the lack of watertight bulkheads, life preservers on deck, and regular communication.

Elsaesser, too, was mostly spared. Yes, maybe he could have struck more sail, or struck sail sooner, or turned the boat this way instead of that, but how could he have predicted such a wind?

Ever succinct, Flanagan simply says, “I wouldn’t believe what armchair sailors say. They’re sitting in their armchairs.”

Of course, the larger question was whether the ship should have been out in the first place. No answer satisfies everyone. Some say absolutely not, others say risk is the tax you pay for adventure.

The Lazzaros and Schacks felt the organization had been negligent, and each family filed a claim. According to Pride of the Sea, a book about the sinking by former Sun journalist Tom Waldron, both claims were settled by early 1988 with payouts in the low six figures.

Vinnie’s mother, Maria Lazzaro, now 82, says, “I wasn’t myself for quite a while. With time, I realized it doesn’t do any good to bear [any ill will].”

In that vein, all the survivors—immediate and otherwise—have gone on.

Leslie and Sugar Flanagan remain married and live in Washington State, having raised two daughters aboard their historic schooner, Alcyone.

Leslie and Sugar Flanagan remain married and live in Washington State, having raised two daughters aboard their historic schooner, Alcyone.

James Chesney also lives in Washington State with his wife, Susan, who he met on the tarmac at Martin State Airport after returning from the sinking. She worked for the Pride organization. Together, they’ve raised two kids and still sail, though Chesney notes that his boat is “fiberglass, very little wood.”

Joe McGeady, now a father of five, lives in Maine with his second wife and works as a mate on a tugboat in New York Harbor for Vane Brothers, a Baltimore company.

The only Pride survivor still living in the Baltimore area, Scott Jeffrey runs the Geospatial Applications program at the Community College of Baltimore County in Catonsville. He lives nearby with his wife with whom he has raised two daughters.

Daniel Krachuk now lives outside of Philadelphia with his wife and two young children and works in the city’s shipyards.

The Elsaesser family and friends created a fellowship in Armin’s name with the Sea Education Association at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts where he worked in between stints on Pride.

Similarly, Schack’s mother preserves her daughter’s memory through a scholarship fund at Bryn Mawr.

Susie Huesman declined to be interviewed and Robert Foster Jr. could not be reached for comment.

The city launched Pride of Baltimore II—complete with watertight bulkheads—on April 30, 1988, and with it, a new tradition. But the first Pride is still remembered fondly, especially in the offices of the now nonprofit Pride of Baltimore, Inc.

“For me, it’s the whole story,” says executive director Rick Scott. “It doesn’t begin in 1988. It begins with this first experiment, this novel idea, this bold idea—a symbol for a city. It’s the very fabric of our identity.”

Aside from Pride II, the most visible reminder of that original symbol can be seen off Key Highway at the base of Federal Hill. Here, a ship’s mast juts from the ground, ringed by a walking path and shrubbery. This quiet memorial could move as part of the planned redevelopment of Rash Field, but its possible new location is not yet known. Scott hopes it will be nearer to the intersection of Key Highway and Light Street for added prominence.

Fittingly, the monument contains the names of those lost at sea. But the last word is Elsaesser’s, culled from the final log he sent back to Baltimore before the sinking.

“What lies ahead is unknown—a source of mystery and apprehension—perhaps the allure of the sailing life—always moving, always changing, always wondering what the next passage will be like and what we will discover at the other end.

“This time, our destination is home—the Chesapeake Bay and Baltimore. It is always a relief for the captain, and I suspect, the ship, to have our lines ashore and fast where Pride is safest—the finger piers at the Inner Harbor.”