Arts & Culture

The Midway’s Final Evening: The Block’s Only Non-Strip Club Bar Closes After Decades-Long Run

Like The Block itself, The Midway became a Baltimore institution simply by surviving.

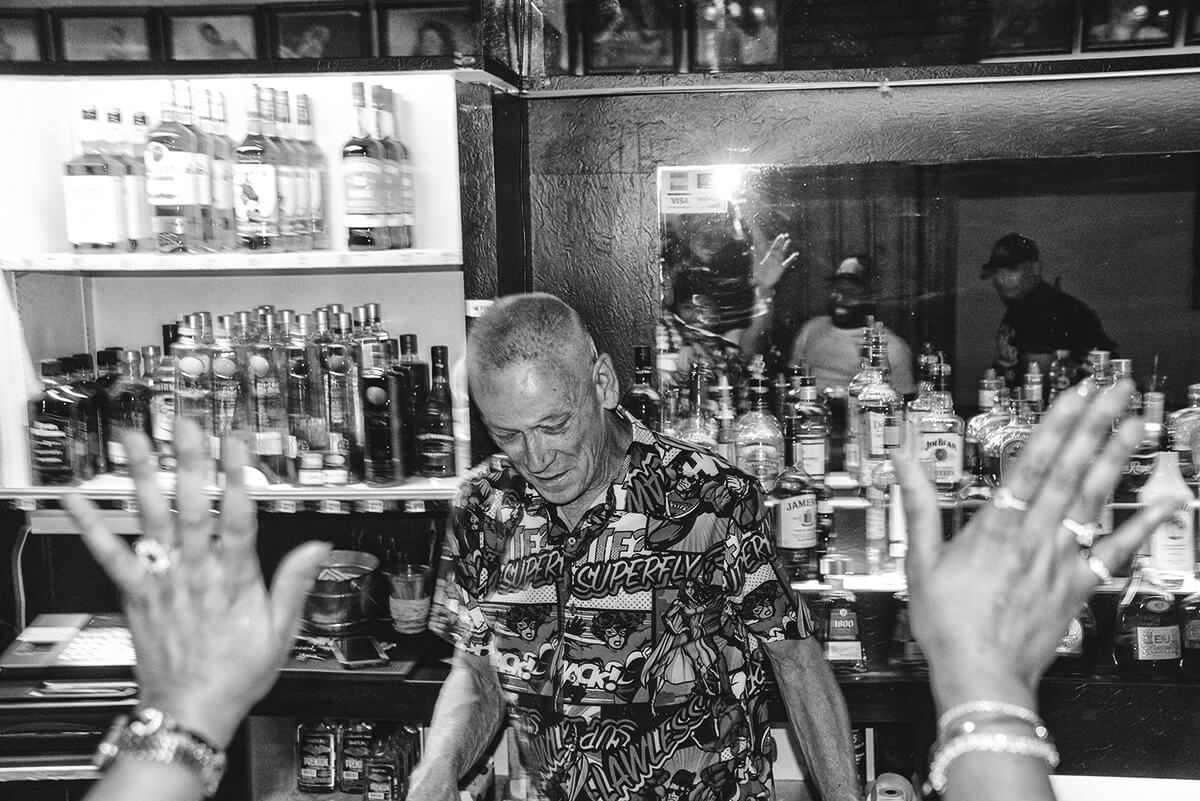

“I started working when I was 15. Came from a poor family and quit school to help out,” says 71-year-old Walter Hardesty, by way of explaining why tonight is his last shift at the Midway, the one bar on this stretch—halfway, appropriately, between Commerce and Gay streets—without a stripper pole and stage. “My first job on The Block was washing dishes across the street at Crazy John’s. Then I became a line cook. Eventually I started tending bar. My knees just can’t take standing up all night anymore. By the time I leave [after cleaning up and counting the money], it’ll be 6 or 7 in the morning.”

Crazy John’s is still across the street, serving scrapple, eggs, burgers, and fries all night on the weekends. The iconic Midway, however, is being retired this late summer evening along with Hardesty, who became irreplaceable over his decades-long career here.

Dive bars may be nice places to visit, but working at one can take its toll. Owner Jim Brandt, whose mother, Vicki, tended bar at the Midway for 35 years, currently pulls the day shift. He says he’s had enough, too. “I’ve got my own health issues,” he shrugs. “I’m ready to sell it.”

Although there are no scantily clad dancers peeling their clothes for tips, the Midway is unequivocally a part of The Block’s culture. Ringing the entire establishment’s throwback wood paneling is its famous collection of 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s glamour shots, including young women from The Block’s burlesque heyday, the unmistakable Blaze Starr among them. Like most of The Block’s bars of that era, the Midway has a colorful, if checkered past. Not as bad as others, perhaps.

But go back to, say, the early and mid ’60s, and the Midway’s liquor license—along with since-departed red-light district bars like Club Tahiti, 704 Show Bar, and Mickey’s Mix-Up—was occasionally suspended for permitting solicitation. “For anyone to say that he was not aware of what was going on down there is hypocritical,” the liquor board chairman said of the bust. “Everyone knew what was going on.”

More common was Midway’s association with numbers running and what the newspapers used to call “the rackets.” In 1961, a grand jury approved subpoenas for the business records of 26 bars, including the Midway, among others on The Block. In 1977, the liquor board found an illegal lottery, run by a fellow named Benjamin “Big Nose Benny” Fooksman, operating out of the Midway.

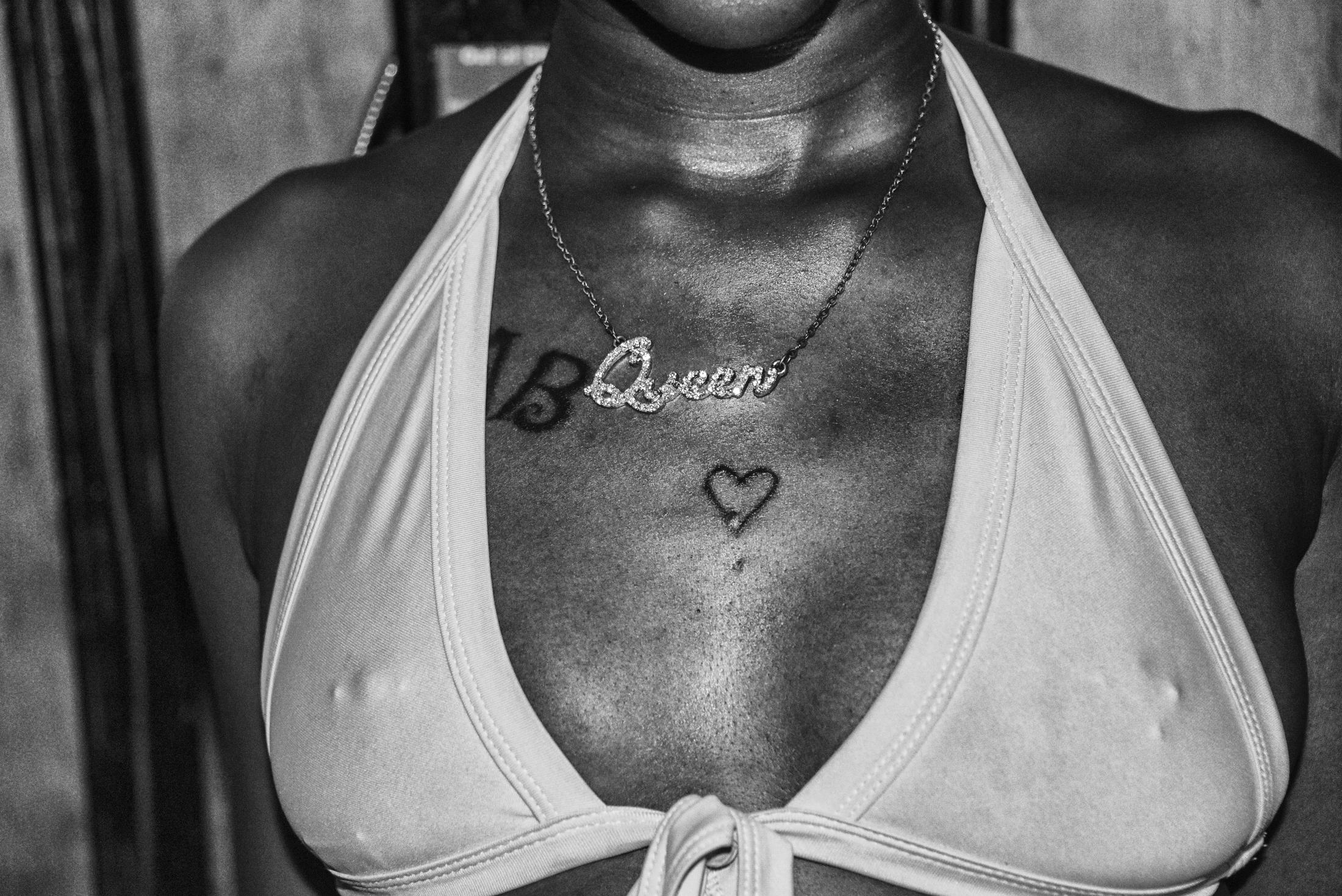

Not that all the old stories are negative. Former Sun columnist Michael Olesker once recalled legendary Midway bouncer Joe Finazzo knocking out a bully who was harassing a couple of female patrons, not once but twice in the same night, each time with a single blow. A former prizefighter, Finazzo was a gentlemanly 71 at the time. Meanwhile, situated above the Midway all these years has been Tattoo Charlie’s. Opened in 1938 by Charles Geizer, it catered to inebriated sailors on leave and is believed to be one of the longest continuously operating tattoo parlors in the U.S.

It is remarkable that while politicians have been attempting to shut down The Block for decades, the Midway has remained, essentially its neighborhood bar. It’s the place where dancers, doormen, shift workers, servers, and bartenders, whose schedules were not 9-5, would come for cocktails and comradery.

Like The Block itself, it became a Baltimore institution simply by surviving. (In 1994, Gov. William Donald Schaefer authorized a massive Block raid, which resulted in more than 50 arrests, half of which were quickly dropped. The same year, Mayor Kurt Schmoke signed legislation designed to “clean up” The Block, expressing his hope it’d all be gone in 10 years. Earlier this year, state Sen. Bill Ferguson put forward a plan that would’ve established a 10 p.m. curfew for bars on The Block. Bar owners and others pushed back. It failed.)

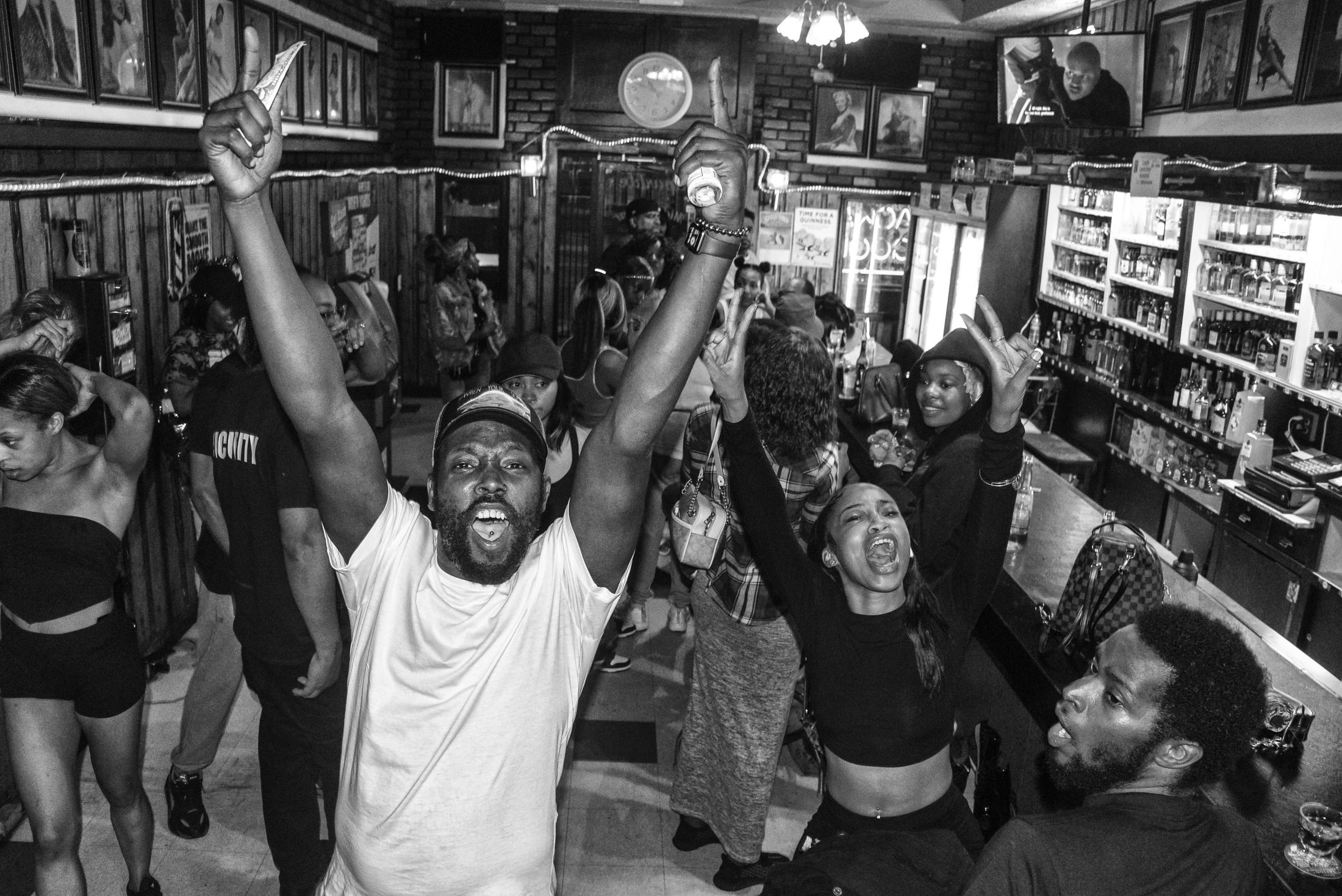

None of that is on the minds of regulars at Hardesty’s send-off, however, which includes two people who actually have glamour shots up on the wall. One is “Mama” Jackie, one of the first Black women to dance on The Block in the 1970s and something of a mother figure to younger women who earn a living on The Block now.

The other is Hardesty himself, in stunning drag, also in a professional shot from the 1970s—which he takes down and holds up to the jaw-dropping amazement of the regulars on hand, who never would’ve guessed in a million years that the almost-50-year-old photo was anything other than that of another Block beauty.

“Let me tell you what makes this place special and what makes Walter, in particular, special,” Mama says, smiling and taking a seat across the bar from Hardesty after bringing a cake for the occasion. “Walter treats everyone with respect. He always has. That is all there is to it. When you’re here, you’re not judged by what you do, but by who you are. That’s the way it’s always been.”

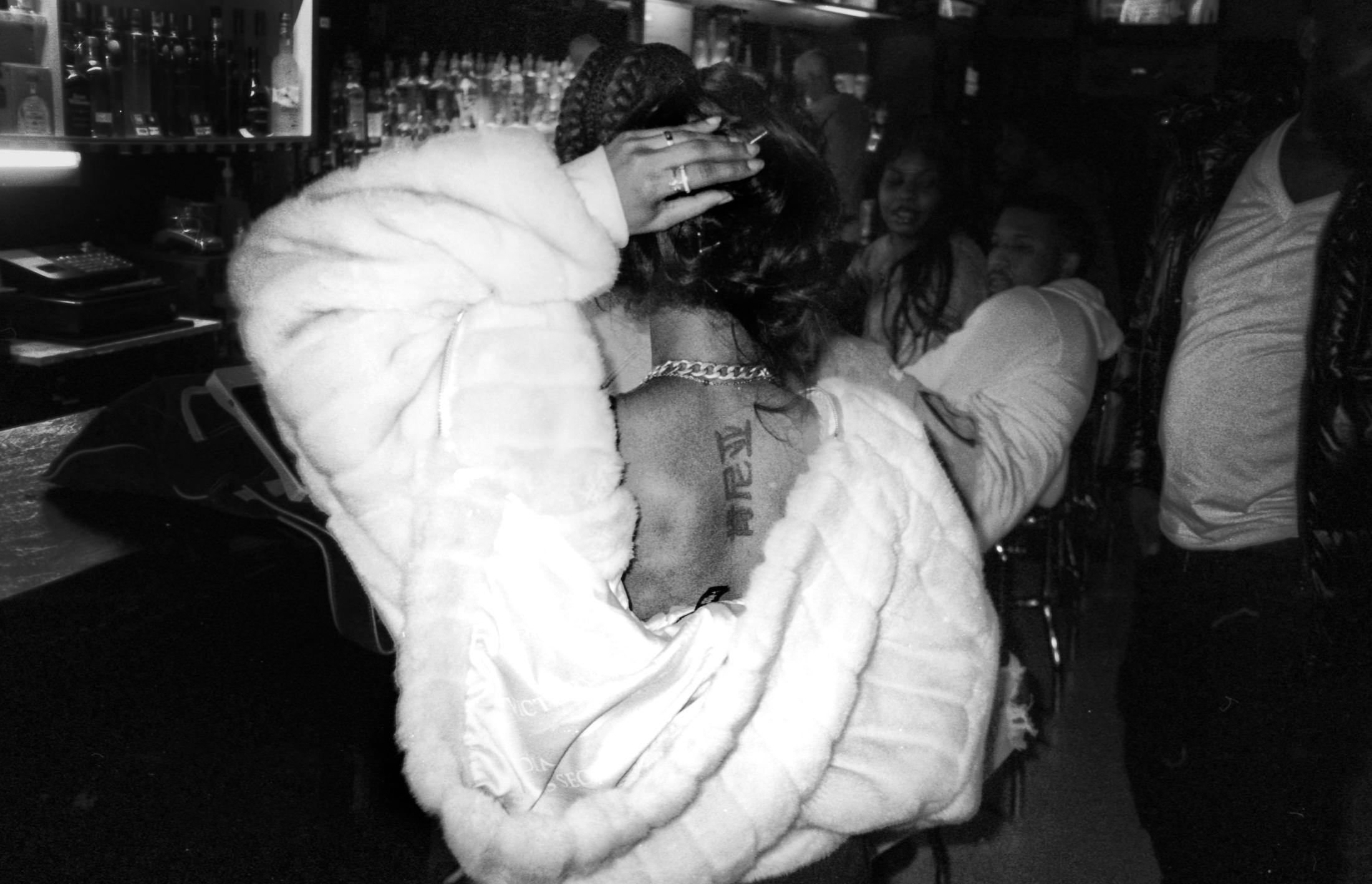

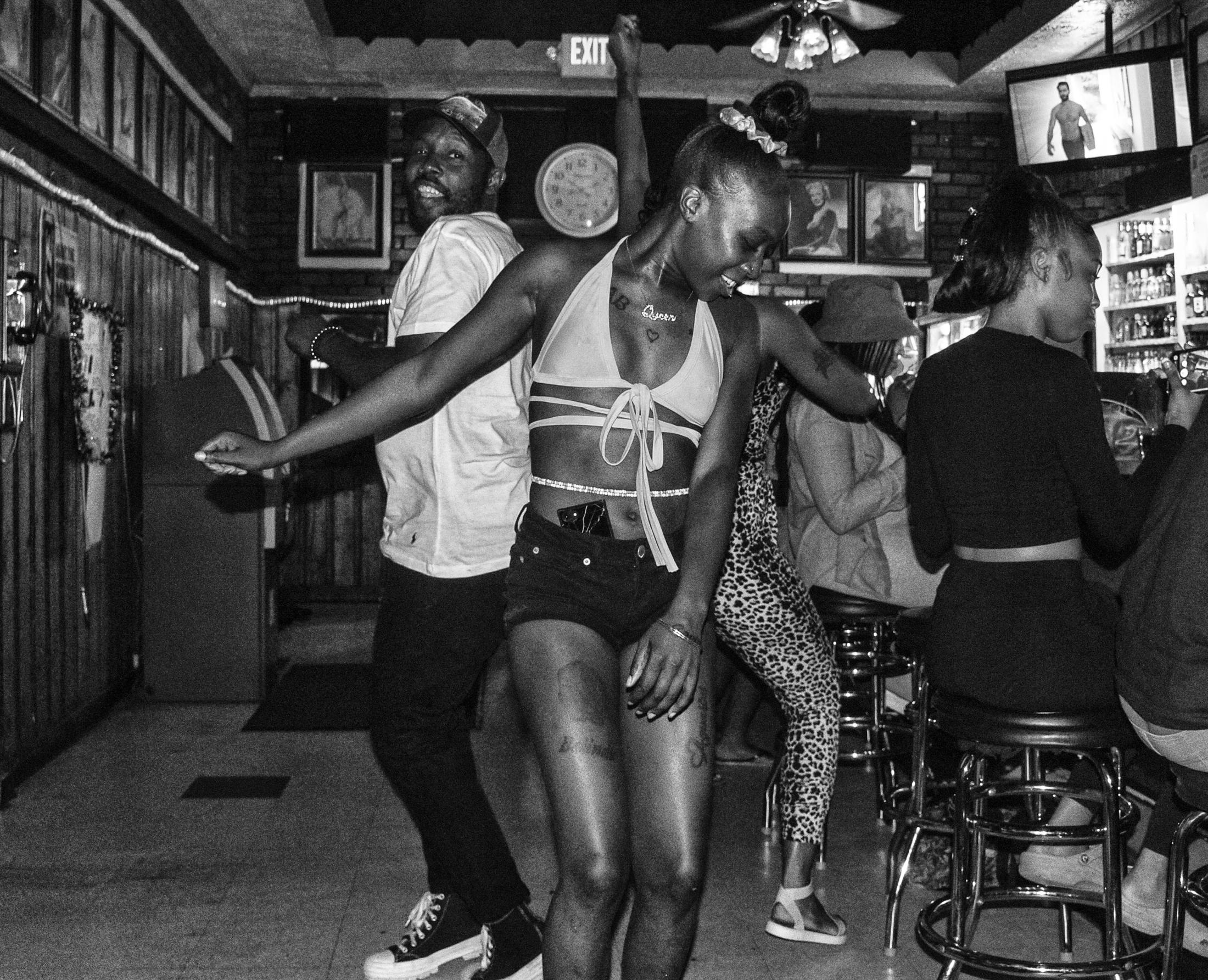

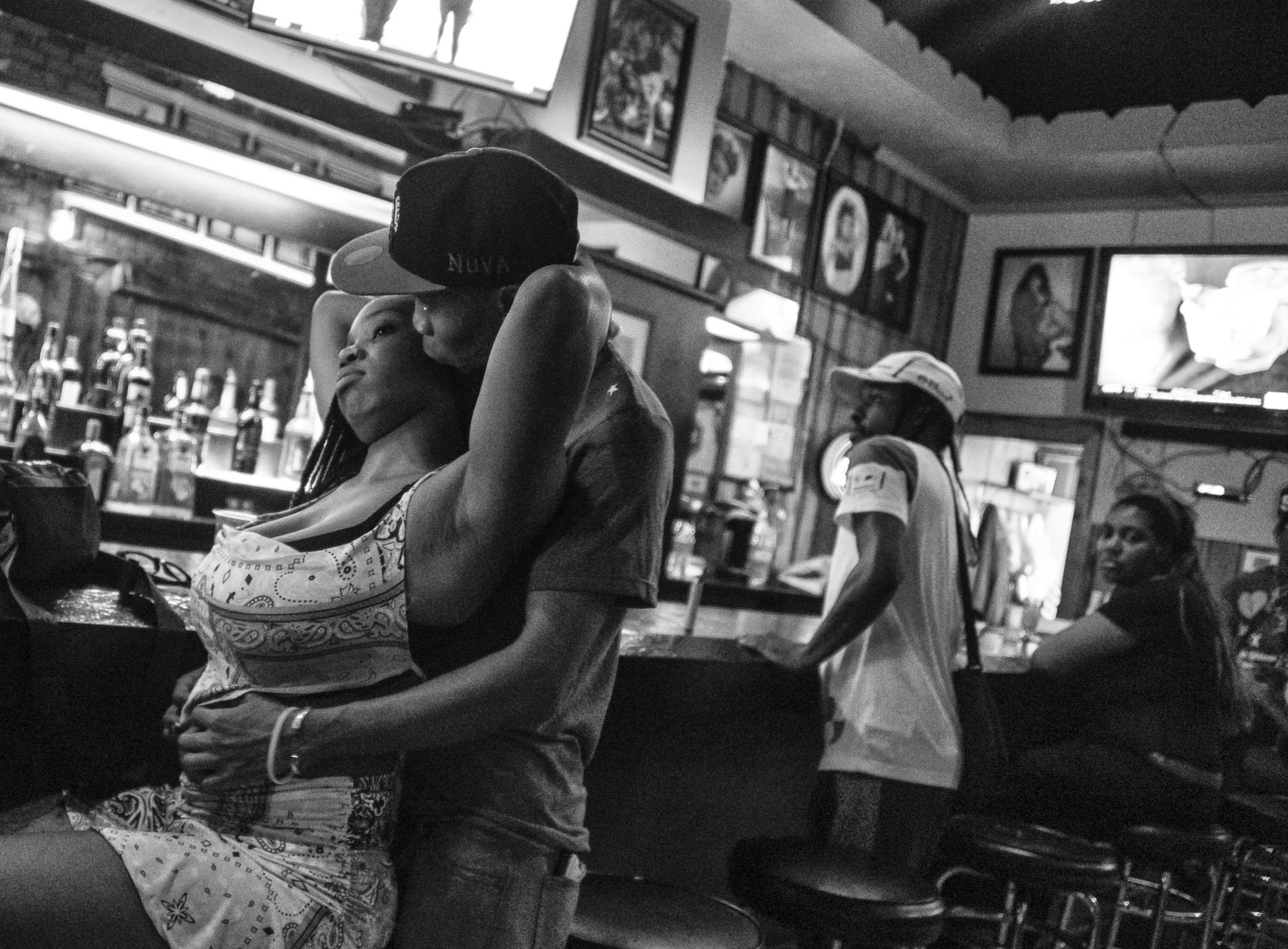

Photojournalist and Baltimore contributor J.M. Giordano documented The Midway’s final nights of service at the end of July.

“The closing of the Midway is devastating to The Block,” Giordano says. “Dancers, ‘runners,’ house moms, dealers, and even other bartenders felt at home at the Midway between shifts. It was a safe place where dancers and sex workers looked after each other and where they could talk to Walt, the last bartender in the bar’s long history.

“For this series, I thought the only way to really capture the humanity of the place was to snap in black and white. I was reunited with my bestie, Ilford 3200 ISO film, which has been invaluable in all of my night work. The Midway was a place where if they didn’t know you, you didn’t take photos. I’m honored that I was allowed to take these, a visual eulogy for a place and time that will never be again.”

Below, Giordano captures the energy of the hallowed bar’s final hours.