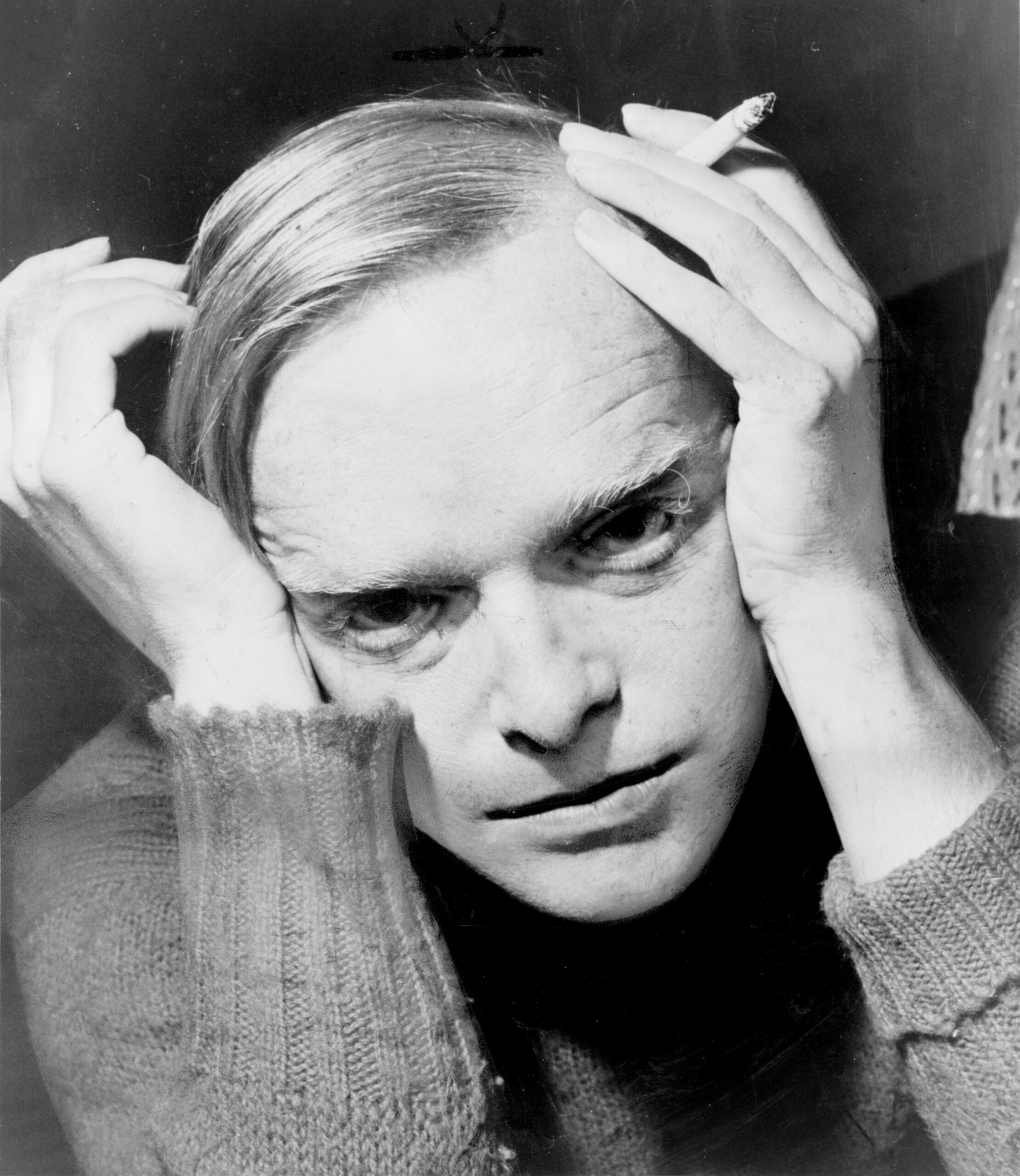

For decades John W. Ruark has told the story at cocktail parties: how on a November night in 1977, as a student at what was then Towson State University, he took Truman Capote’s arm and led the inebriated, incoherent, profanity-spewing writer off stage.

“Mr. Capote,” he told him, “It’s time to go.”

A crowd of about 1,800 people had come to the university’s Towson Center to hear Capote read from his work, according to a report that week in The Towerlight, the school newspaper. Capote’s appearance–rambling and spiced with F-bombs–lasted only 10 minutes. The abrupt ending made for sensational headlines nationwide. Ruark, then student government president, told reporters about chaperoning Capote through the event—from hotel to Towson and back again.

But he only told part of the story.

“There are things that happened I felt uncomfortable sharing,” Ruark says. “I am a different person now than I was then.”

Decades later, Ruark, 66, is a wealth-management planner living in Miami, and Nov. 13, 1977 is a piece of his personal history. It’s also become a piece of literary history that, like Capote himself, is a provocative mix of gossipy entertainment and tragedy. That day, Capote publicly proclaimed himself a “genuine alcoholic” and told a reporter with the Baltimore News American that his Towson State reading would be his “final farewell.”

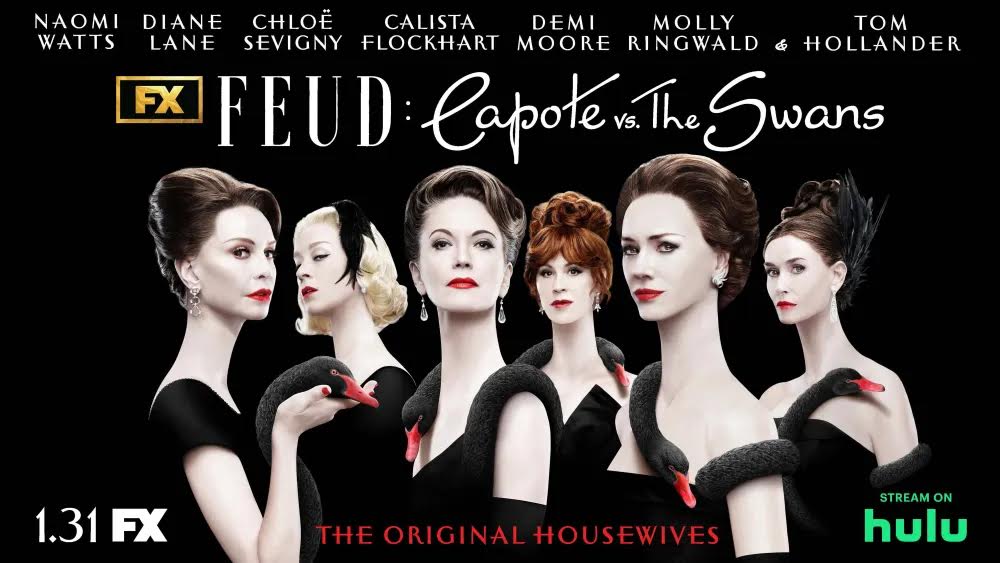

But Capote isn’t the sort to just go away. Nearly 40 years after his death, the author of In Cold Blood and Breakfast at Tiffany’s—himself the star of countless cocktail parties—remains endlessly fascinating. Capote vs. the Swans, an eight-episode season of the Ryan Murphy anthology series Feud, premiered this week on FX and Hulu. The show depicts Capote’s exile from a flock of New York socialites—a banishment that intensified his uncontrollable drinking and drugging.

Which led to that Sunday night in Towson.

Two years earlier, Capote had published “La Côte Basque 1965” in Esquire magazine. Its main characters were Capote’s wealthy women friends—thinly disguised. They felt betrayed by Capote’s use of the infidelities and petty secrets of their lives, so they ostracized him. He recounted later to the New York Times that this painful exile led him to visit five psychiatrists and check into a rehab facility to kick pills and booze.

But those struggles hadn’t ended when he arrived at the Hunt Valley Inn ahead of his talk.

When Ruark came into Capote’s room, he found the 53-year-old writer in the company of a man he recalls Capote describing as “my young friend.” Ruark was about 10 minutes early, so Capote said he’d like to use the bathroom.

And there he stayed.

Ten minutes became 15. The young friend knocked on the door, but Capote wouldn’t come out.

“Are you aware that Mr. Capote just got out of rehab?” Ruark remembers the young friend saying. Ruark hadn’t known that.

“He hates talking in a public forum like this,” the young friend said.

Fifteen minutes became 20, and at last Capote emerged. On the drive, Ruark discerned a change in Capote’s demeanor. The writer began to mumble and murmur in what Ruark calls “that unique voice of his.” It’s a voice once described as sounding like a hamster on helium. But Capote’s words didn’t make sense. By the time they reached Towson, it was clear to Ruark that Capote had ingested some intoxicant and couldn’t carry off the talk.

He found David Nevins, a former student government president who since graduating had joined the university’s administration, and who was on hand to help with the event. Nevins, who had started the school’s speaker series, recalls looking forward to Capote’s talk.

“Truman Capote was as famous then as Oprah Winfrey is today,” he says.

But Ruark motioned toward Capote. “This guy,” Ruark said, “I don’t know what he’s on, but I don’t think he’s going to be able to give the speech.”

What to do? Let him speak? Stop him? Nevins, who now owns a public relations firm in Towson, remembers an associate of Capote’s insisting that he’d be okay to give the talk. Ruark remembers learning that they had to let Capote try. Stop him and the student government would be liable for Capote’s $3,500 fee. But if Capote couldn’t deliver, then the failure would be his. He’d violate the contract, and the student government could keep his fee.

“It was important to me not to screw up the financial part of it,” Ruark says.

On the way to the podium, Capote tripped. He dropped his reading glasses. When Ruark picked them up, Capote spat at him: “Fuck you!” Nevins remembers Capote throwing a book into the audience, then singling out people and calling them “fat” and “slovenly.” According to The Towerlight, Capote announced, “I’m going to read you something I like and if you don’t like it, to hell with you.” Ruark, though, recalls “to hell with you” as another F-bomb.

“We could not use that kind of language in public at the time,” Ruark says. “We took him from both sides. He didn’t say ‘stop’ or anything like that.”

“He was sort of childlike in his response,” says Nevins. “He just kind of looked and oddly smiled.”

“I was quite shaken,” Ruark says. “But we got him to the car.”

Nevins went back to the podium and apologized to the crowd. “It’s the most applause that I’ve ever gotten anywhere at any time,” he says.

Back in Hunt Valley, Capote’s young friend and Ruark puzzled over how to get Capote out of the car and back to his room. Capote wouldn’t move, and couldn’t keep his feet. Small, he might have weighed about 130 pounds at the time, Ruark tossed Capote headfirst over his shoulder, then headed for the lobby.

And this is what he didn’t tell reporters. As they passed through the lobby, Capote, still slung over Ruark’s shoulder, squeezed one of Ruark’s butt cheeks and said, “You have a nice ass.”

Why withhold this detail? Because Ruark was then a 20-year-old man from Salisbury, on Maryland’s conservative Eastern Shore, struggling in less open-minded 1977 toward coming out as gay.

“I’m coming out of the closet,” Ruark says now, “and oh, my gosh, this man’s grabbing my ass. What do I do?”

What he did was lay Capote carefully on the hotel room bed, then hurry back to his dormitory to deal with fallout from the event.

Other speakers who came to Towson State that year performed without a hitch. Ruark graduated after majoring in economics. He’s now married, happily out, and contributes to LGBTQ+ causes. He’s still pleased to tell the story of his encounter with Truman Capote, and how, despite the tension and sadness of it all, Capote still delivered the evening’s ass-grabbing punchline.

Ruark never considered Capote’s actions harassment or oppressive. “I just literally thought it was funny,” he says.

Capote continued his cycle of addiction and celebrity until his death at age 59. Complaining to an interviewer a year after the Towson event, he said he didn’t understand why people had made such a big deal of his behavior that night.

“My goodness,” he said, “you’d have thought I killed the Lindbergh baby.”

Michael Downs is a former newspaper journalist and past director of the graduate program in professional writing at Towson University. He has published three books, most recently a novel, The Strange and True Tale of Horace Wells, Surgeon Dentist.