Arts & Culture

By Lawrence Burney

Illustration by Klawe Rzeczy

Opening Spread

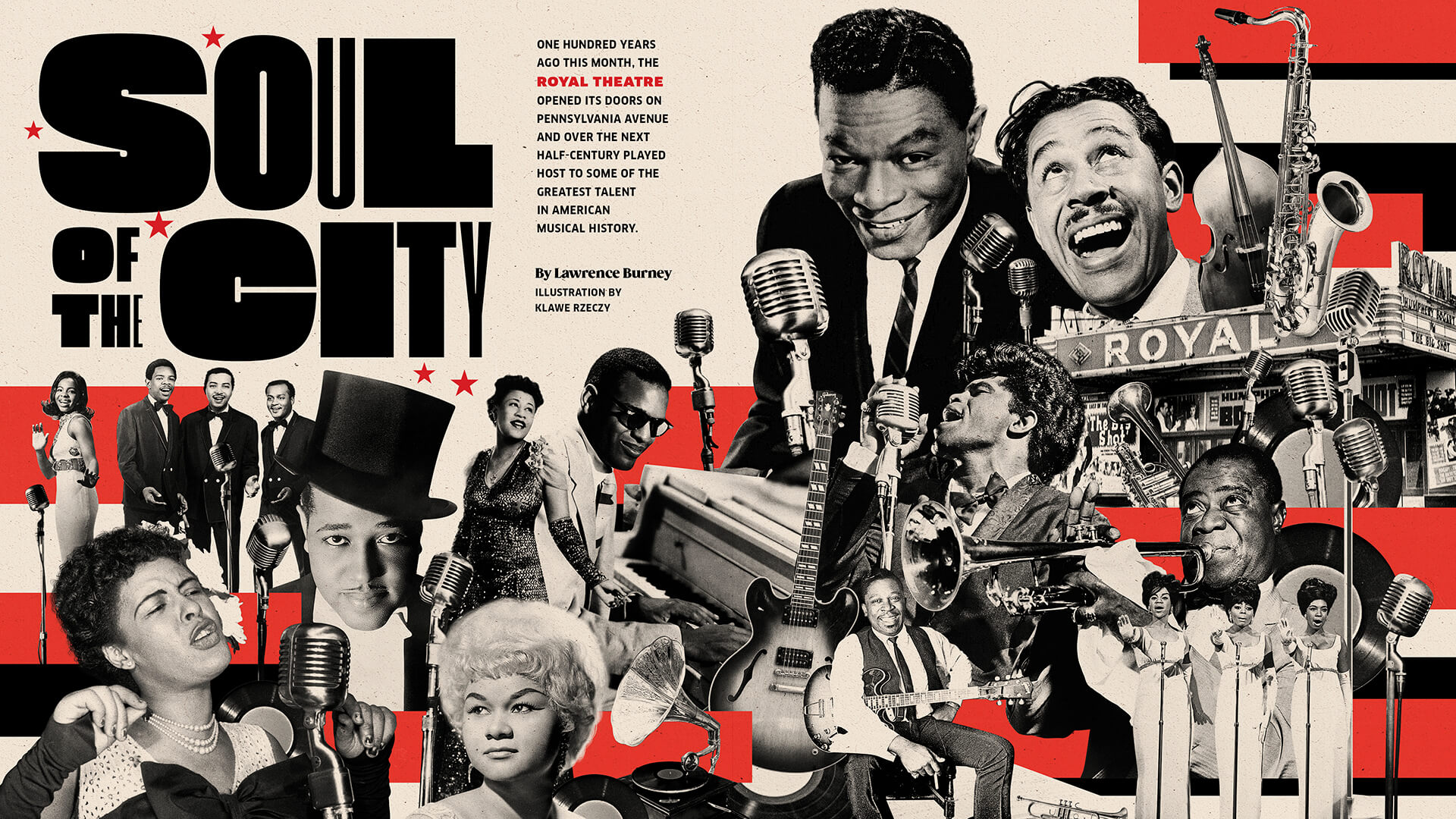

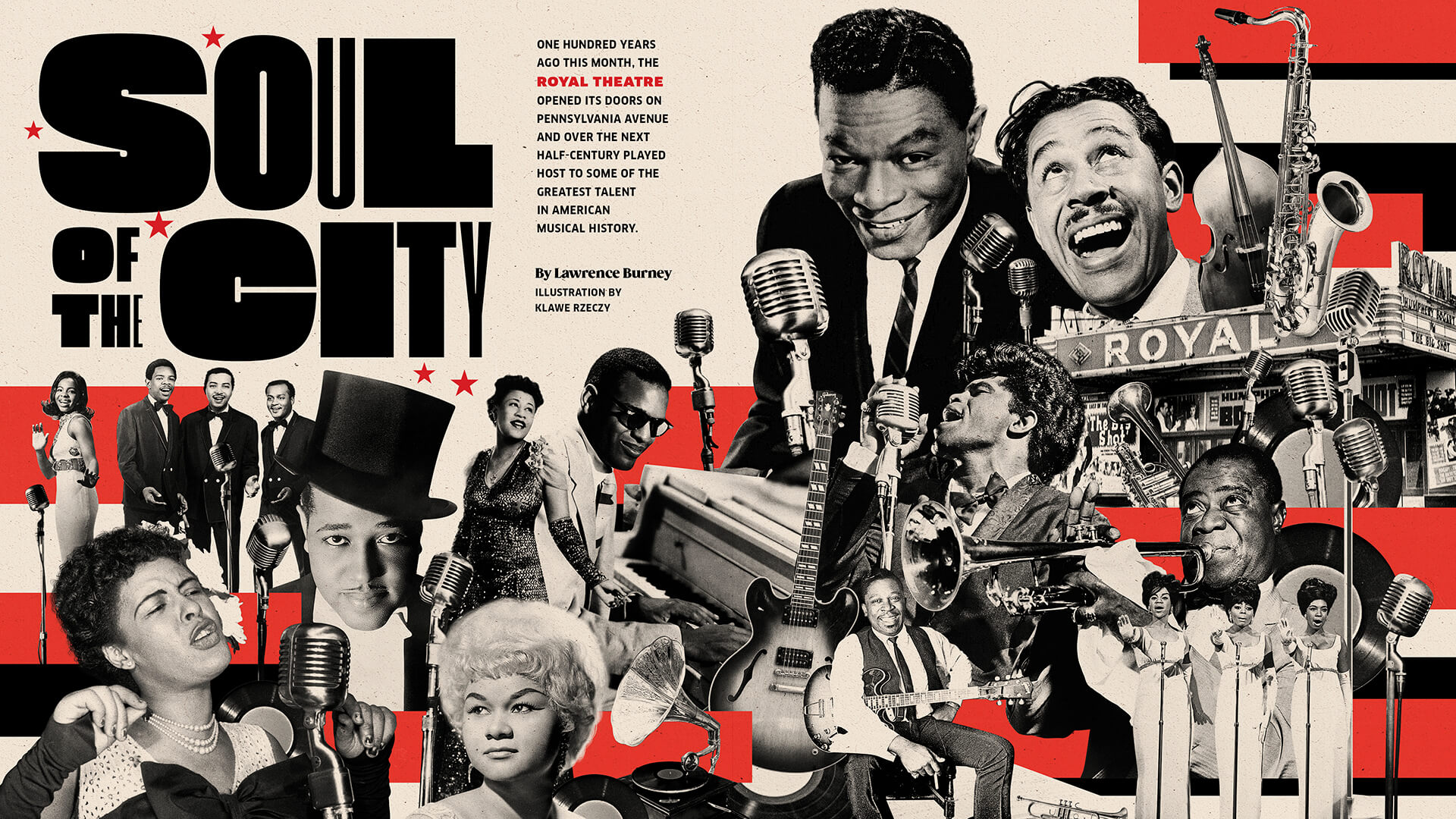

A collection of just some of the icons

who took the stage at the Royal Theatre.

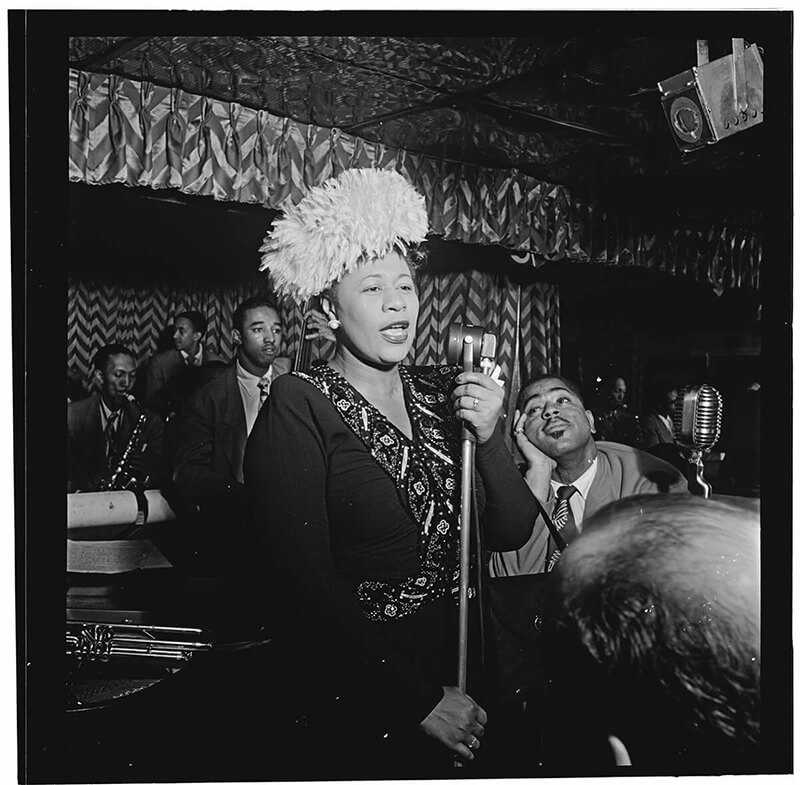

A COLLECTION OF JUST SOME OF THE ICONS WHO TOOK THE STAGE AT THE ROYAL THEATRE.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT, GLADYS KNIGHT & THE PIPS, DUKE ELLINGTON, ELLA FITZGERALD, RAY CHARLES, NAT KING COLE, CAB CALLOWAY, LOUIS ARMSTRONG (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS), THE SUPREMES, JAMES BROWN (GETTY IMAGES), B.B. KING, ETTA JAMES, BILLIE HOLIDAY (GETTY IMAGES).

Doris Hill took her six-year-old son Guy, my grandfather, from their home at the Lexington Terrace low-rise apartments in West Baltimore to nearby Pennsylvania Avenue’s main attraction, the already legendary Royal Theatre. Guy wasn’t completely sure of the occasion, but judging by the venue and what he’d known about it up until that point, he figured they had come for an early evening movie. For all of its fame of being a premiere Chitlin’ Circuit music hall for the first half of the 20th century, it’s rarely mentioned anymore that the Royal also served as a community cinema. But when young Guy entered the main theater that night and saw a stage in place of the big projection screen he expected, he realized he was in for something different than a motion picture. As he and my great-grandmother settled into their seats, the first person who came to the microphone startled him. It was the evening’s emcee, who, in comedic fashion, had walked to center stage dressed in a suit jacket, white shirt, black tie, socks, shoes—and boxer shorts. Part of his bit was a joke about how someone had broken into his dressing room and stolen his pants. Even at six, my grandfather still recalls he was a little shocked by how crass it all seemed. But soon after warming up the crowd with a few laughs, the host introduced the headliner for the night, a Chicago singer named Gene Chandler, who was on his way to becoming a huge star throughout the country that year.

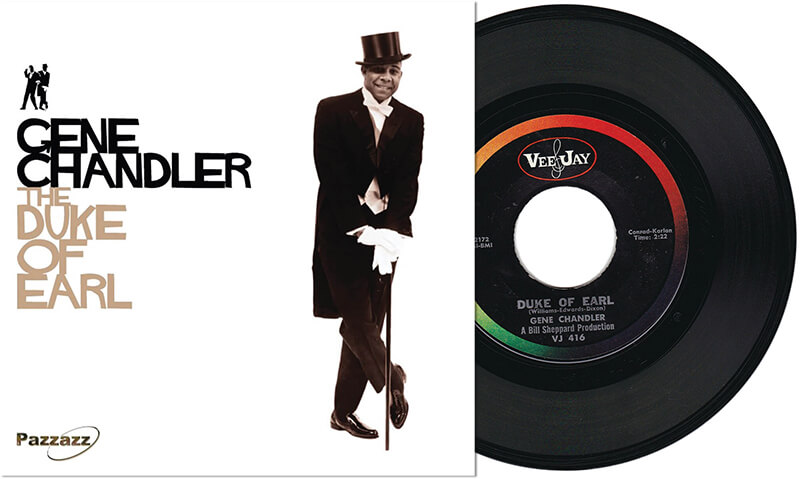

Guy didn’t recognize Chandler when he was introduced, but for months he’d been singing his soon-to-be chart-topping doo-wop single, “Duke of Earl,” which he’d heard over and over on the radio and everywhere in his neighborhood.

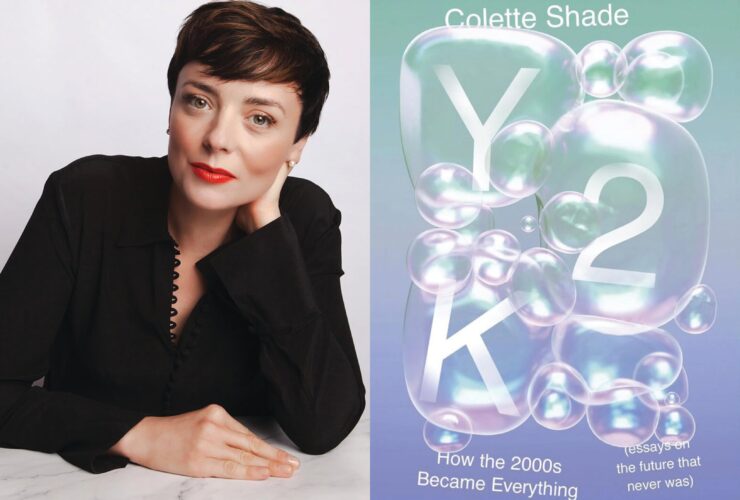

Singer Gene Chandler of “The Duke of Earl,” appeared at the Royal in the 1960s.

Duke, Duke, Duke of Earl

Duke, Duke, Duke of Earl

As I walk through this world

Nothing can stop the Duke of Earl

In a sultry voice in front of a packed audience, Chandler and his band, The Dukays, harmonized their pursuit of a young woman they’d like to make “the duchess” of their imaginary royal world. Just a couple of months later, “Duke of Earl” would peak at number one on the Hot 100 charts and stay there for three weeks. Once Guy’s first-grade brain was done computing that he could now place a face to the hit song, he watched the performance in wide-eyed amazement. The evening became a destiny-shaping experience.

“That was an electrifying moment for me,” he says, six decades later, the excitement reentering his psyche. “After that, I just had this buzzing need that, you know, that’s what I wanted to do. That’s where I wanted to be. I wanted to be on a stage.” And he got there, too. Years later, Guy Curtis would drum with Parliament-Funkadelic on European, American, and Canadian tours, share stages with people like Bootsy Collins, Lenny Kravitz, and members of the Red Hot Chili Peppers. “That is the biggest backdrop of my young memory.”

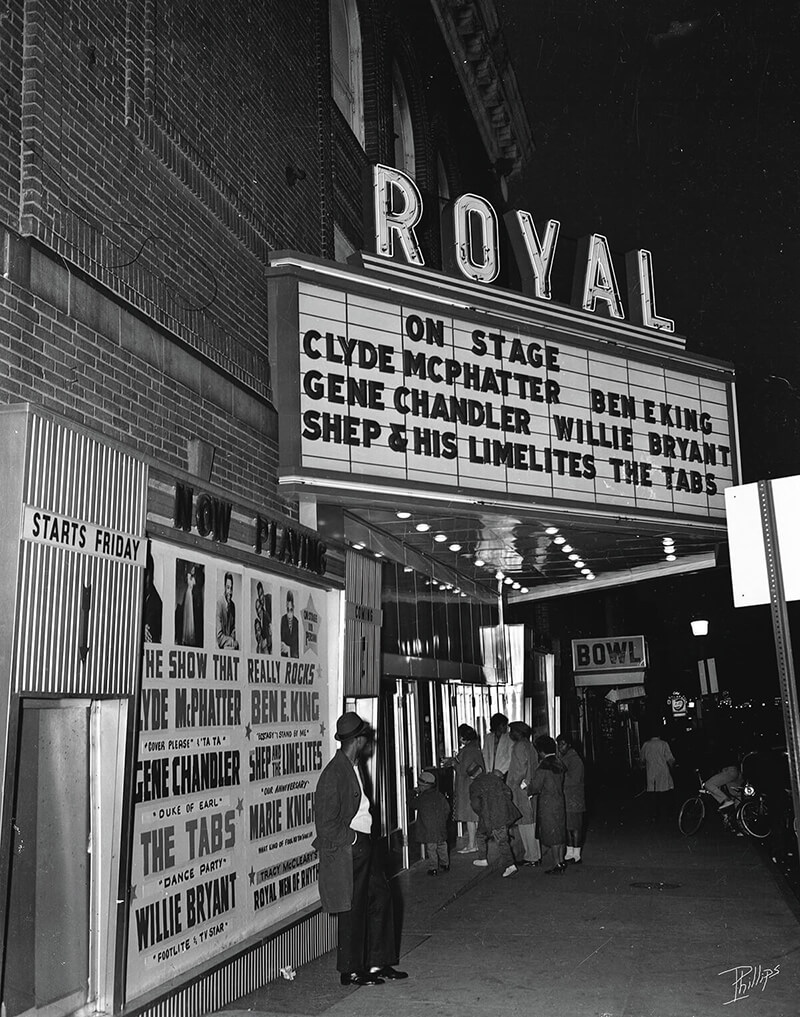

A line at the Royal, which was both a music hall and cinema. Credit: Courtesy Theatre Talks/Cezar Del Valle.

WHAT WOULD eventually become the Royal Theatre opened its doors 100 years ago this month, on Feb. 15, 1922. Initially, it was a fully Black-owned venue called the Douglass Theatre that specialized in movies, traveling comedy, and Black vaudeville shows. Live animal and circus acts took the stage from time to time, too. A few months prior to its opening, an ad in Baltimore’s Afro-American Newspaper had alerted local residents of its near-arrival and encouraged the Black community to make a financial investment in its genesis:

Afro ad for the Douglass Theatre, the Royal's original name. Courtesy of the Afro-American Newspaper.

“YOUR LAST CHANCE: Open in February 1922. Cost $500,000. Most beautiful theatre owned by colored people south of Philadelphia. Are you a part owner?”

Within a few years, however, the Douglass Theatre went from being a promising endeavor brought to fruition by Black Baltimore to a white-owned venue renamed the Royal, with a history and legacy that is as complicated and rich as the West Baltimore neighborhood where it stood before being demolished to make way for “urban renewal” in 1971.

The theater would never return to Black ownership, but for nearly a half-century the Royal would play host to many of the greatest, groundbreaking musicians, singers, and performers of the 20th century while primarily serving the city’s Black community. The list of iconic headliners over the decades boggles the mind today: Marian Anderson, Ma Rainey and her Georgia Jazz Hounds, Bessie Smith, Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, Louis Armstrong, The Count Basie Orchestra, Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, Etta James, Ray Charles, Little Richard, B.B. King, Bo Diddley, Stevie Wonder, The Supremes, Smokey Robinson and The Miracles, Gladys Knight and the Pips, and on and on. James Brown recorded a live album at the Royal. When Martha and the Vandellas shouted out Baltimore in their 1964 Motown classic, “Dancing in the Streets,” it was genuine—they were booked for an entire week at the Royal that year. Not to mention, saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker was once a member of the house band, the renowned Royal Men of Rhythm.

And then there is Baltimore’s own Cab Calloway and especially Billie Holiday, whose 8-foot, 6-inch bronze statue across the street from where the Royal once stood serves as both a monument to her transcendent talent and a testament to the theater’s role in American music history.

The Royal Theatre became storied in its own right, but historian and Baltimore native Philip J. Merrill also wants people to remember how it got its start with the help of the local Black community.

“I think it was so cutting-edge and so ahead of the curve,” Merrill says about the advertisement and early interest around the Douglass. Merrill, who authored the 2020 book, Old West Baltimore, specializes in historic Old West Baltimore’s past. “Here you have Clark Smith, a Black attorney who is a member of the Maryland bar, as well as the New York bar, that’s able to be the legal general counsel to get people interested in developing and supporting this pioneering cause. I’m in love with the concept of the Douglass and Black folk buying stocks and shares. And the other thing that’s exciting about the Douglass, is that a lot of people don’t understand [that] it even was called the Douglass”—an homage, of course, to a certain former Baltimorean who escaped slavery and became the most influential abolitionist in U.S. history.

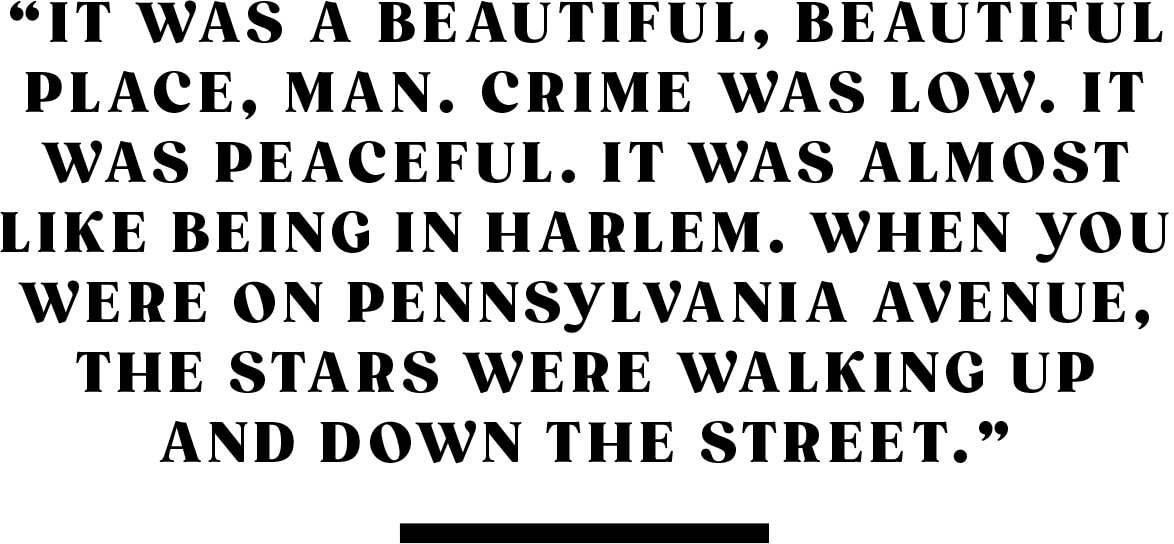

Gene Chandler and Ben E. King on the marquee; Billie Holiday on Pennsylvania Avenue. Photography by I. Henry Phillips.

SOMETHING THAT’S crucial to note is that Pennsylvania Avenue, as a whole, was somewhat of a Black oasis from the ’20s to the ’60s. It was filled with restaurants, clothing stores, markets, barbershops, and movie theaters on its main strip and side streets, from Penn North down to Franklin Street. While the Royal may have been the biggest draw, it had plenty of help from its neighboring businesses in creating a vibrant culture throughout historic West Baltimore. In those days, Baltimore generally ranked as the sixth or seventh largest city in the country, with a population that regularly flirted with a million. It was commonplace for American music’s biggest Black stars to stroll down The Avenue while in town a few days before or after a gig.

“Oh my, the whole of Pennsylvania Avenue was something in the evening,” Rosa Pryor-Trusty, a West Baltimore native and former singer, promoter, and club manager, told Baltimore several years ago. “Women stepping out in their dresses, with their fancy hats and gloves. The men putting on their best three-piece suits and polished, patent-leather shoes. Everybody walked The Avenue, going from one theater or comedy club or nightclub to the next.” Banned from downtown’s segregated hotels, many of the most famous musicians and performers in the country stayed in the heart of Old West Baltimore. They lodged at one of the neighborhood’s three small Black hotels, or at a boarding house or with a local family, or, sometimes, at the Black Baltimore Musicians Union Hall, which still stands in the 600 block of Dolphin Street.

“It was a beautiful, beautiful place, man,” my grandfather reminisces with a near sigh in his voice, clearly thinking about how West Baltimore has changed over the years. “Crime was low. It was very peaceful. It was almost like being in Harlem or something. When you were on Pennsylvania Avenue, the stars were walking up and down the street. They would be in the clothing stores. They’d be buying stuff and a lot of the stores had pictures of the owners with the artists that would come through. Walls would be decorated. Smokey Robinson, Diana Ross, James Brown. I mean, come on.”

THE ROYAL, along with spots like The Sphinx Club, the Club Casino (owned by legendary former numbers runner and entrepreneur “Little Willie” Adams), the Closet Club, The Red Fox, Gamby's, the Avenue Bar, the Tijuana Club, which hosted Miles Davis and John Coltrane, and other clubs along Pennsylvania Avenue also did their part in nurturing the local jazz and soul talent coming out of Baltimore City.

Billie Holiday, the internationally adored jazz singer, grew up as a young girl in Fells Point and made her living in the beginning by playing in clubs along The Avenue. Acclaimed singer and swing band leader Cab Calloway, and his lesser-known singing sister Blanche, cut their teeth in the same area after growing up and going to high school in West Baltimore. The same goes for Chick Webb, a prominent swing music drummer who was born and raised in the city. And for Ethel Ennis, Baltimore’s “First Lady of Jazz,” who grew up in Sandtown-Winchester. Her mother, Bell, played piano at the nearby Ames United Methodist Church on Baker Street. Her younger brother, Andrew Jr., played saxophone and clarinet, and eventually joined Ray Charles’ band. Ennis would go on to perform with Bennie Goodman, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie, Lionel Hampton, Louie Armstrong, and with Cab Calloway at the Apollo in Harlem. In 1984, she and husband Earl Arnett opened Ethel’s Place across the street from the Meyerhoff, bringing top shelf acts to their club from Wynton Marsalis to Yo-Yo Ma.

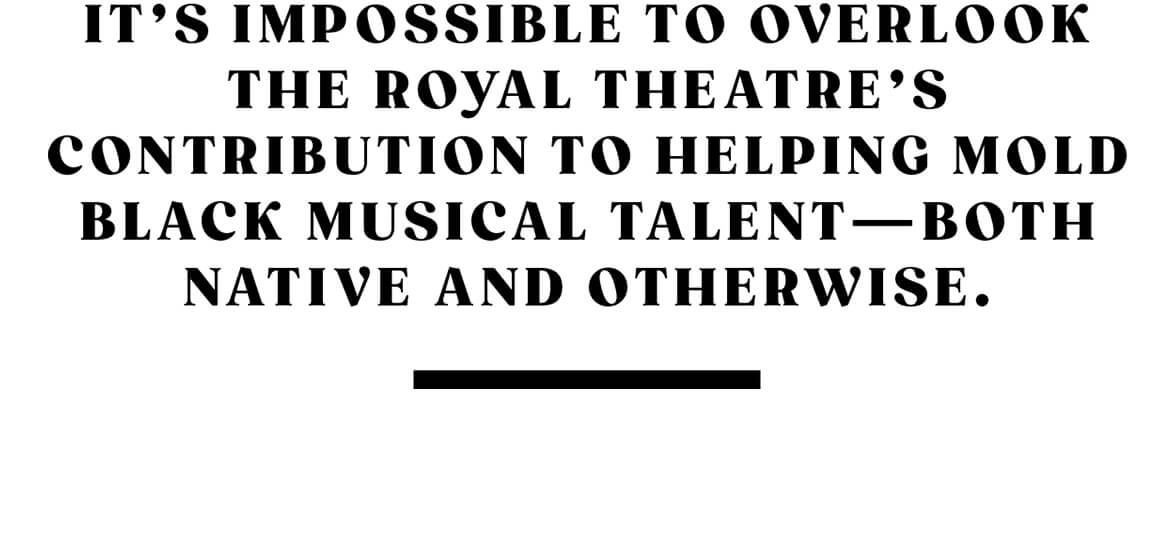

It’s impossible to overlook the Royal Theatre's contribution to helping mold Black musical talent—both native and otherwise—that went on to influence people who aren’t even aware of where that influence stems.

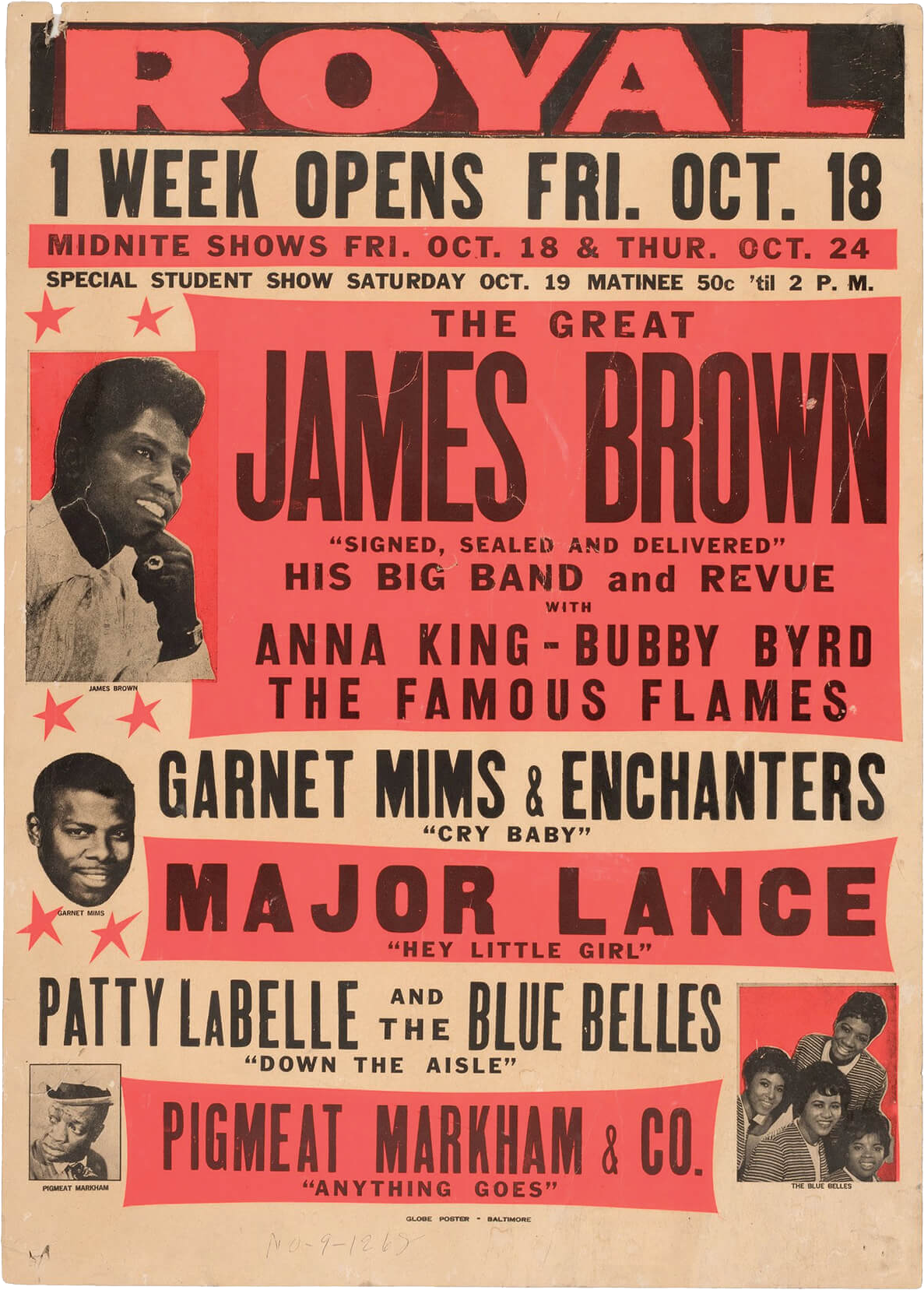

Consider that in November 1963, James Brown and The Famous Flames, the group he started out with before going solo, recorded Pure Dynamite! at the Royal, one of the 15 live albums he released throughout his career. A flyer for that night informed concertgoers that it would be recorded, which by the sounds of their uncontained elation throughout the album, was probably the extra fuel the crowd needed to come with their best screams, howls, and sing-along voices. The album is only 30 minutes long and made up of eight songs that had already been released at that point. “Like A Baby” and the extended version of “Oh Baby, Don’t You Weep” are studio recordings that were dubbed with live crowd noises afterward so they could blend in. Still, Pure Dynamite! remains an indispensable Baltimore artifact because it’s one of the few pieces of documentation of the Royal that gives you a true feeling of what it was like to be there when the biggest star of the time was front and center. It’s the equivalent of someone 60 years from now stumbling across a video of Beyoncé performing at M&T Bank Stadium during her Formation Tour in 2016. On “Shout and Shimmy,” for example, an onslaught of drumming, combined with Brown’s wails, are met with whistles and screams. A quarter of the way through, when Brown yells, “I feel alright!” the audience responds with an impassioned, “Yeah!” And when he follows with, “You know I feel pretty good, children,” and asks people to stand up and shout if they feel as good as he does, they come through with an even louder, “Yeah!”

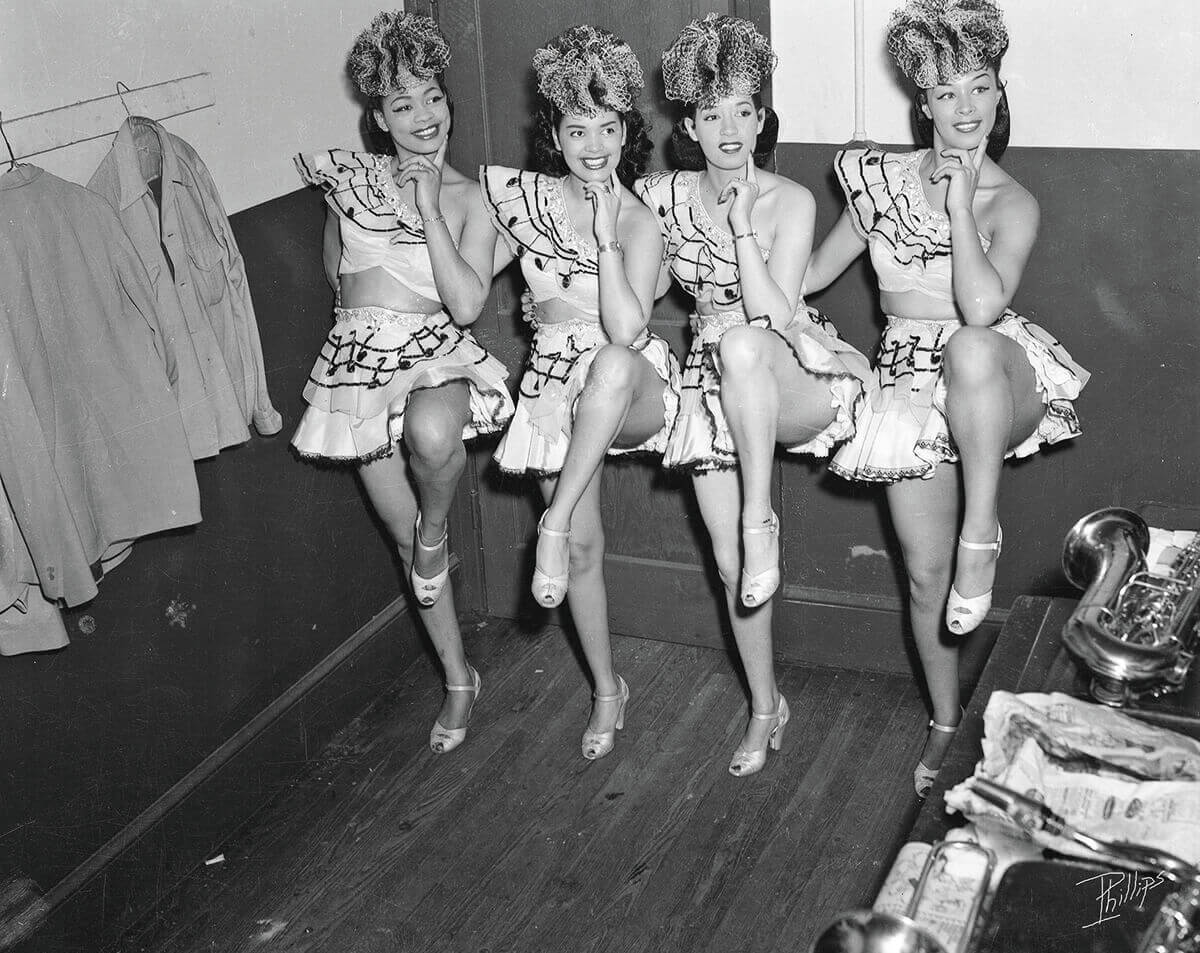

The audio is crunchy, but much of it resembles the part of a church service when the percussionists, organ player, and vocalist join forces in hopes of helping someone catch the Holy Ghost. It’s an example of what made the Royal such an exhilarating sanctuary for Black music: It housed so many musical alchemists whose names and styles became part of the everyday contemporary lexicon. Duke Ellington, who was from neighboring D.C., started to play at the Royal frequently in the 1930s. By then he had created his own signature sound within jazz called jungle music, which he’d developed during a four-year residency at New York City’s Cotton Club. The Supremes helped revolutionize what R&B girl groups would look and sound like for decades to come. Singer Etta James—whose work spanned from gospel to rock ’n’ roll to blues and whose classic "At Last" has been covered by Adele and Beyoncé—played the Royal several times a year. (Although she didn’t remember it too fondly in her later years. After her death in 2012, The Baltimore Sun published a 2007 interview where she said, “Now that was a bum theater. Everybody that ever went there would be terrified to go . . . people would come in there with pickles, with olives, with boiled eggs and get ready to throw all kinds of stuff at you . . . Baltimore was always a really raunchy city, compared to Washington, D.C.”)

IN NOVEMBER 1963, James Brown and The Famous Flames, the group he started out with before going solo, recorded Pure Dynamite! at the Royal, one of the 15 live albums he released throughout his legendary career. A follow-up to his Live at the Apollo the year before, the album, taking its title from Brown’s nickname, “Mr. Dynamite,” reached the Billboard charts, peaking at No. 10.

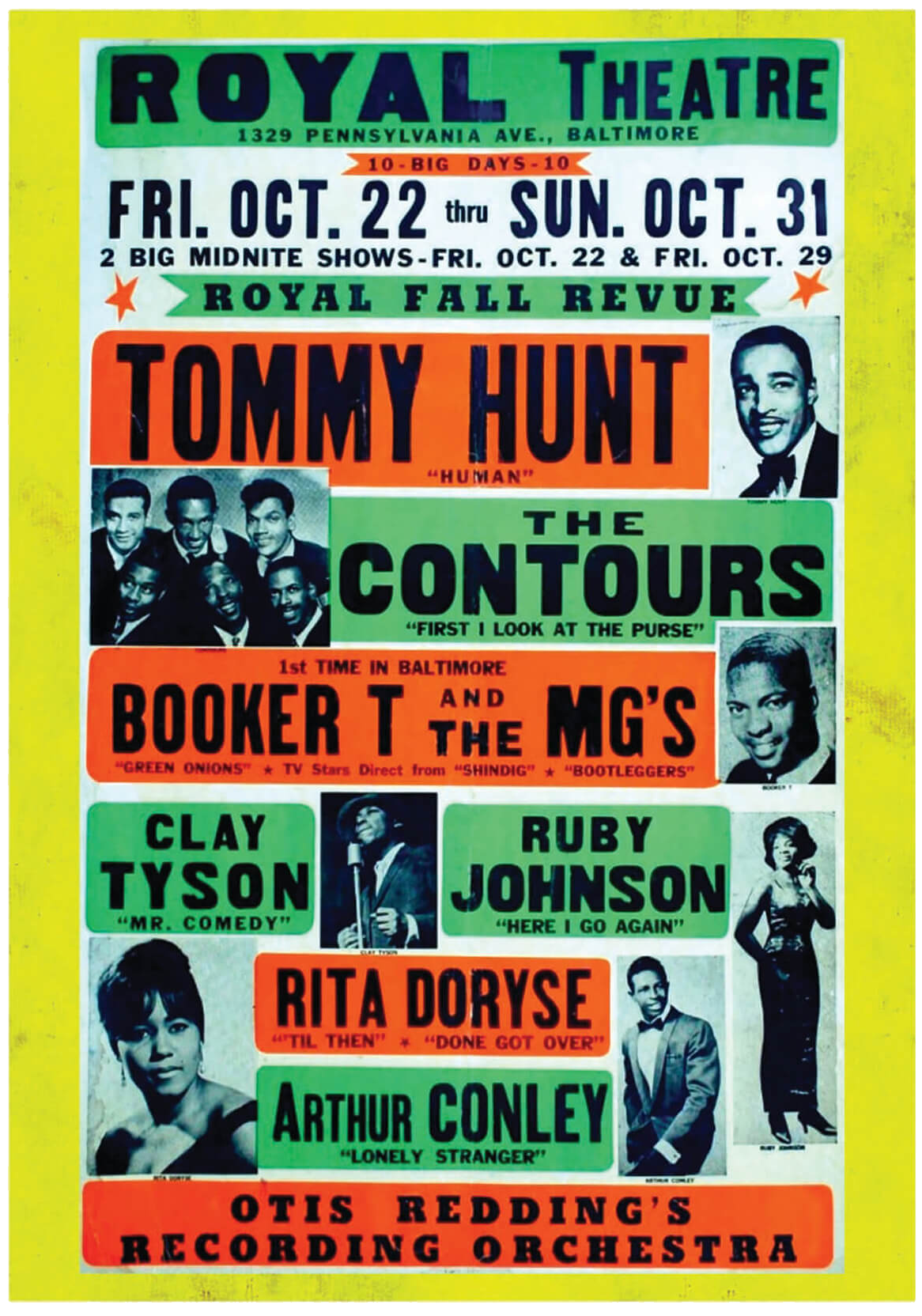

GLOBE POSTER Once one of the largest printmakers in the United States, Globe was revered for its music and entertainment posters that promoted state fairs, carnivals, drag races, and, most notably, show bills for the leading soul and R&B acts in the country. Globe ceased operations in 2010 and the Maryland Institute College of Art holds their collection.

45 records from Frankie & The Spindles, James Brown, Ray Charles, and Etta James. Vintage Globe posters advertising James Brown and Patti LaBelle and The Blue Belles, and Tommy Hunt and Booker T and the MG’s. Wikipedia Commons, Discogs & Globe Poster

Count Basie at the piano during a stint with his orchestra at the Royal. Photography by I. Henry Phillips.

OVER THE YEARS, I had heard a few versions of how my grandfather, who grew up in the same low-rise with the people who’d go on to inspire The Wire’s central characters, became a fixture in Baltimore’s music scene for the next 50 years. After getting the performance bug, he wanted to be a star, not just the guy gigging in the background. As a teenager, he tells me now, he set out to learn every instrument, produce his own music, and handle the vocals. The Royal had already been shuttered by the time he reached adolescence, but he started to enter talent shows in the area, where he typically excelled, and managed to learn the keys, bass drum, and some saxophone.

Smokey Robinson and The Miracles backstage at the Royal. Robinson returned to Baltimore in 2002 to help raise funds for the Royal Theatre Marquee Monument. Photography by I. Henry Phillips.

Down at the courtyards of Lexington Terrace, once he entered junior high, my grandfather started to weasel his way into the huddles of dudes in their teens and 20s who had their own singing group and would be rehearsing their songs, shooting dice, and drinking right behind his family’s apartment. Their stage name was Frankie & The Spindles and they were steadily becoming one of the biggest R&B groups in Baltimore, if not the whole East Coast. “They would push me away, like, ‘Go ahead, boy.’ You know, they were a little older than me and I was like a kid at that time,” Guy says with a laugh. “But they always looked out for me.” Lucky for him, the group’s guitarist was a friend’s older brother and offered to give him some lessons on playing. He saw Guy’s potential and, by the time he was about 14, Guy would accompany Frankie & The Spindles to various clubs on Pennsylvania Avenue where they’d plead with venue owners to let him on stage if they promised to look after him. And he took full advantage. Once he got older, seasoned musicians who’d compliment him on his guitar-playing skills gave him all the positive reinforcement that he needed. “It was my early start in being fearless,” he says. “I didn’t care who I played with, what level they was on stage, or how great they were.” Frankie & The Spindles went on to play at area clubs for the next decade or so, in addition to touring up and down the East Coast with The O’Jays.

In my lifetime, my grandfather worked as a cab driver in the city throughout the week, jammed with his musician buddies in our basement every few days, and gigged on the weekends. But musician or simply music lover, talk to anyone old enough to recall the Royal and they’ll share similarly vivid memories of the theater and the artists who performed there, suggesting it’s still very much alive in the hearts of those who got to experience it. “I never got to perform at the Royal, but it was okay because I had that memory of my mom taking me there,” my grandfather says. “And that’s part of me, always. I will never, ever forget that because that’s what sparked me into wanting to be a musician.”

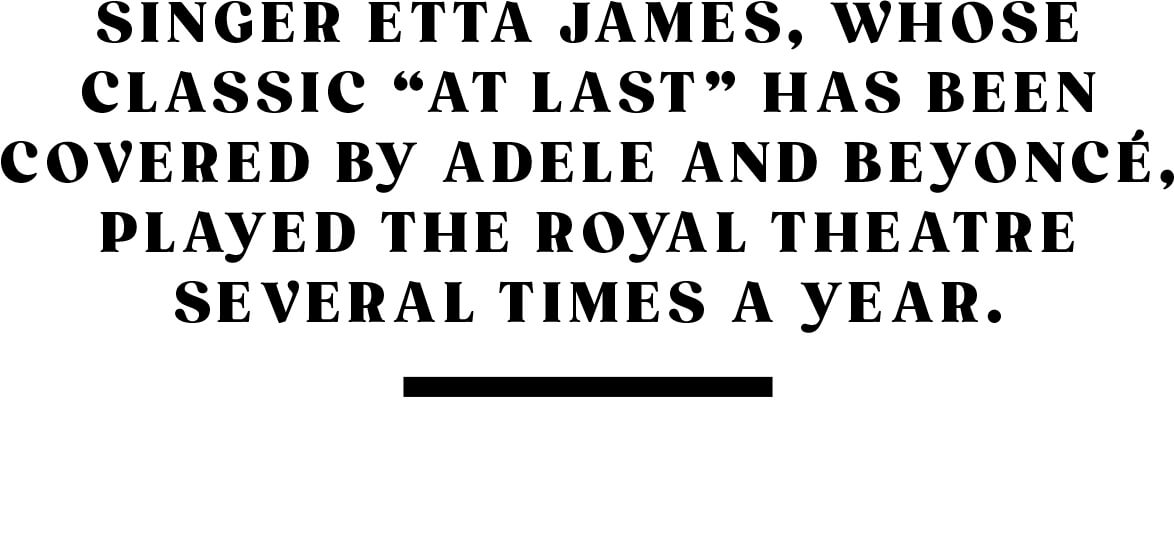

Billboard ads outside the Royal. Photography by I. Henry Phillips.

FOR A BLACK PERSON who has grown up in the post-1968 unrest version of Baltimore City, the lure and legend of the Royal—Pennsylvania Avenue as a Black entertainment mecca, neighborhood quartets singing on street corners, rowhouses that aren’t dilapidated, and a relatively low crime rate in our communities—feels like nothing short of blind romantic nostalgia. The Baltimore that we’re familiar with has remnants of this culture, but it’s mostly in the spirit and stories of our elders, who, if we’re lucky, have made some effort conveying to us that we are part of a lineage that’s greater than the dysfunction we’re often defined by. I’m lucky to have my grandfather, aunts, and family friends for that. But it is also critical to acknowledge that the need for Black spaces like the Royal, and other hubs along The Avenue which created a more insulated culture, was driven by relentless white lawmakers and white constituents intent on maintaining Baltimore’s centuries-old segregation.

The great trumpeter Louis Armstrong appeared many times at the Royal and donated 300 lbs. of coal to needy residents during a December 1931 visit. Photography by I. Henry Phillips.

The area that Pennsylvania Avenue and surrounding Sandtown-Winchester are a part of—now colloquially referred to as Zone 17—was where much of the city’s Black community lived because of a first-of-its-kind discriminatory housing law put into effect just 12 years before the then-Douglass Theatre opened. Though the 1910 law was created to effectively make integrated residential areas impossible in Baltimore, the result carried over into the city’s entertainment and nightlife scenes. Ford’s Theater in the then-white Howard Street business corridor (not the one where Lincoln was killed in Washington, D.C., although both were owned by Baltimore native John T. Ford) allowed Black people to perform, but Black patrons had to enter through the side of the building and could only sit in the very back rows of the second balcony where they could barely see. Matters became worse when the theater showed a screening of D.W. Griffith’s then-heralded racist propaganda film, Birth of a Nation, in 1916. The local NAACP chapter regularly protested the venue from that point forward. The Lyric, which first opened in 1894 as The Music Hall, allowed Black patrons to sit where they liked, but they were not allowed to perform under any circumstance. In 1944, the Afro-American reported that the Lyric’s managing director at the time, Frederick R. Huber, said the venue would not be made available for a planned NAACP event featuring Duke Ellington and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

My grandfather was just a boy when most of this was going on, but he still recalls the places and neighborhoods that his mother told him not to enter. “I remember they used to tell me that we couldn’t go beyond North Avenue without it being an issue: up into the Reservoir Hill area we wanted to go,” he tells me. “But it was a great place to live and it was all about music. We had the Civic Center and there was always two or three major shows a month. We had the Fifth Regiment Armory, which used to do the same thing. They also had the circus. We had The Ambassador on Gwynn Oak and Liberty Heights. And then you had some venues around the racetrack in the Pimlico area. It’s sad now because they have nothing at all.”

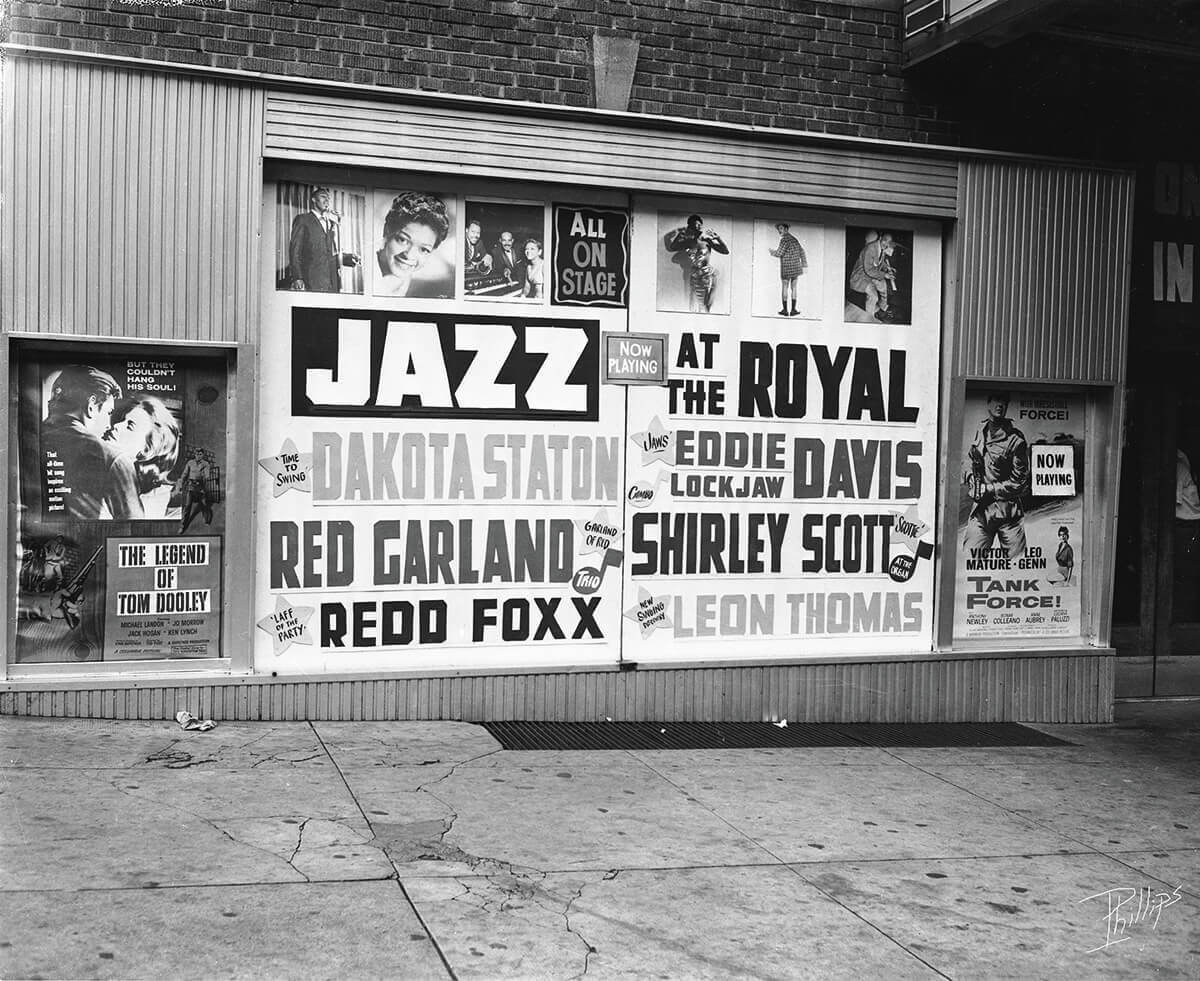

Comedian Redd Foxx had a long-running engagement at the Royal; professional dancers backstage; Ella Fitzgerald on the Royal’s stage; Nat King Cole at the piano. Photography by I. Henry Phillips and Library of Congress.

To hear my grandfather recount the days when Baltimore had more than a handful of legitimate music venues and an overall higher quality of life brings about a mourning for a city that I’ve never come close to experiencing. Today, Pennsylvania Avenue is a shell of its former self. The Royal Theatre is gone and all that’s left in its honor is a faux marquee with its name on it. The neighborhood itself offers little reason to visit unless you already live in the area, other than perhaps an occasional event at the Arch Social Club or Jubilee Arts—or roller-skating at the Shake & Bake Family Fun Center. Much of it has broken down since mainly white business owners fled after the riots in 1968 in response to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Two-plus generations later, that same area was ground zero for Baltimore’s 2015 Uprising in response to the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray, after he suffered life-ending injuries while in police custody.

One of the recent musical bright spots for the Upton/Sandtown area was the national attention starting to be garnered by rapper Lor Scoota. Growing up two blocks from the site of the Royal, he was on the cusp of becoming a leading voice among a new class of young artists representing the feelings and attitudes of inner-city youth. But in 2016, he was tragically gunned down in Northeast Baltimore after leaving an anti-violence charity basketball game at Morgan State University.

All that said, while The Avenue may be full of ghosts today, there is also optimism. In 2019, Maryland designated the area surrounding Pennsylvania Avenue’s business corridor as the state’s first official Black Arts District, offering financial incentives for viable Black nonprofits and businesses to return.

If, in some miraculous string of events, the Royal could be resurrected—there’s long been talk of reviving the venue—it’d be a kind of full-circle moment and moral victory for the city’s Black residents. It for damned sure wouldn’t solve all of our issues, but a victory like that would feel good for most, if not all. (Merrill, the Baltimore native and author, readily acknowledges the Pennsylvania Avenue’s significance as what he calls a “Renaissance pocket,” but he says he’s not in favor of rebuilding the Royal. “We can’t go back in time,” he says.) Award-winning spoken-word artist and activist Lady Brion, the founding director of the Black Arts District nonprofit, which is coordinating efforts in the state-designated area, acknowledges the enormous hurdles in building a new venue.

Diana Ross and The Supremes appeared at the Royal in the 1960s.

“A live performance space, serving Black-curated artists, is one of our big goals,” she says. “There are not enough mid-size performance spaces in Baltimore. There are a lot of 100-seat or less venues, and huge 750-2,000-seat theaters, but not the mid-size, 200-500 space, which is our ideal, and a size venue that the city needs.

“Ask any elder in West Baltimore and they are going talk about the nightlife on Pennsylvania Avenue,” Brion says. “We think this arts and entertainment district can create a new wave of interest in West Baltimore and help to make Pennsylvania Avenue a destination, which will definitely be a way to jump-start the local economy in that area and attract people and businesses here once again. For me, personally, Pennsylvania Avenue represents a high point in Black Baltimore cultural history.”

BILLIE HOLIDAY PROJECT FOR LIBERATION ARTS

Photography by Ron Cassie

FOUNDED BY Johns Hopkins University professor Lawrence Jackson, the mission of the Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts is to collect, document, and share the unique history of Baltimore Black life, culture, and art. For Jackson, a historian, writer, and the author of the award-winning books Chester B. Himes: A Biography (W.W. Norton 2017) and The Indignant Generation: A Narrative History of African American Writers and Critics (Princeton 2010), the creation of the project was part of his return to the city where he grew up. “There is no better location than where we are to explore the figures I’m interested in, in 20th-century history,” Jackson said in announcing the initiative in 2017.

To date, the Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts has created a speaker series in partnership with Black churches, a public arts program, a visiting artist residency, a partnership with public schools, and a free, annual Billie Holiday Jazz Concert at Lafayette Square.

For history buffs, the project has also created the Baltimore Africana Archives Initiative, whose aim is to build an “unprecedented” Maryland collection of Black primary source material, with a focus on local history and culture. Recent acquisitions include 100 of acclaimed Baltimore photographer John Clark Marden’s city photographs shot between 1974 and 2012, and collected material from the late Ethel Ennis, Baltimore’s “First Lady of Jazz,” and her husband Earl Arnett.—Ron Cassie

PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE BLACK ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICT

Photography by Mike Morgan

IN 2019, the state formally designated the Pennsylvania Avenue corridor the city’s fourth Arts & Entertainment District. Building on decades of work by community activists, the critical distinction includes 10 years of tax-related incentives designed to attract artists and cultural organizations—and visitors—while promoting local engagement, investment, and revitalization.

As part of the initiative, spoken work poet Lady Brion (pictured above), the cultural curator at the grassroots think tank Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, founded the nonprofit Black Arts District to coordinate efforts in the nearly 150-acre designated area. Despite the pandemic, the Black Arts District has remained busy, hosting, sponsoring, and promoting virtual and in-person events, including grant workshops, slam poetry competitions, and pop-up vendors at “The Avenue” public market. This spring, they will host the acclaimed Womxn of the World Poetry Slam as well as a Black Arts Fair. Plans also include an outdoor music Legacy Festival in August and a Black Pride celebration in October. Meanwhile, their capital campaign for a new Pennsylvania Avenue arts center continues.

“We haven’t really known anything outside the pandemic,” says Brion. “So our role has been to help Black creatives find some normalcy. To give them places to be creative, to work—both virtually and with in-person gigs—serving a programmatic purpose. Last year, we gave out $100,000 in grants and this year we hope to double that.”—Ron Cassie