Arts & Culture

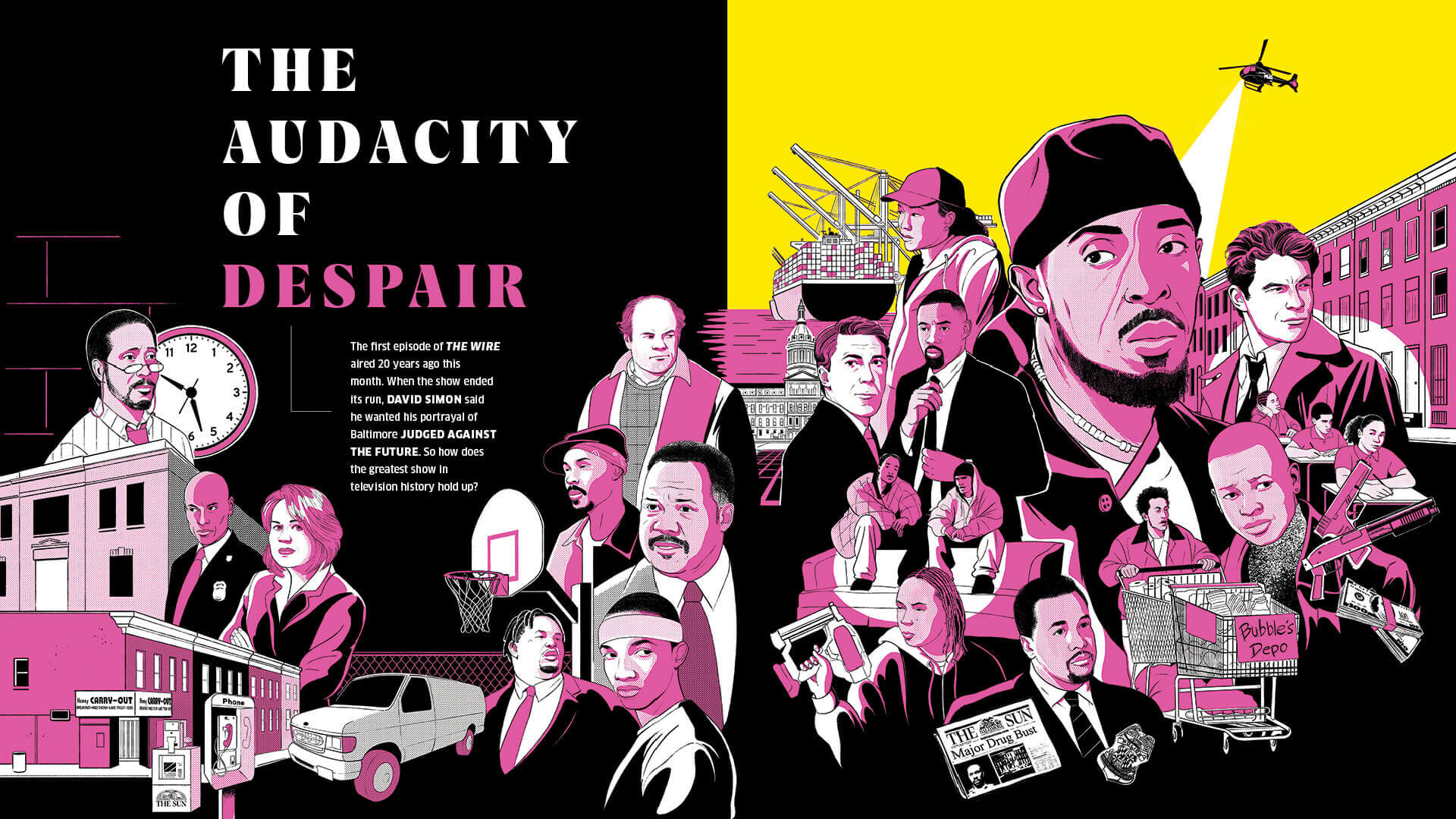

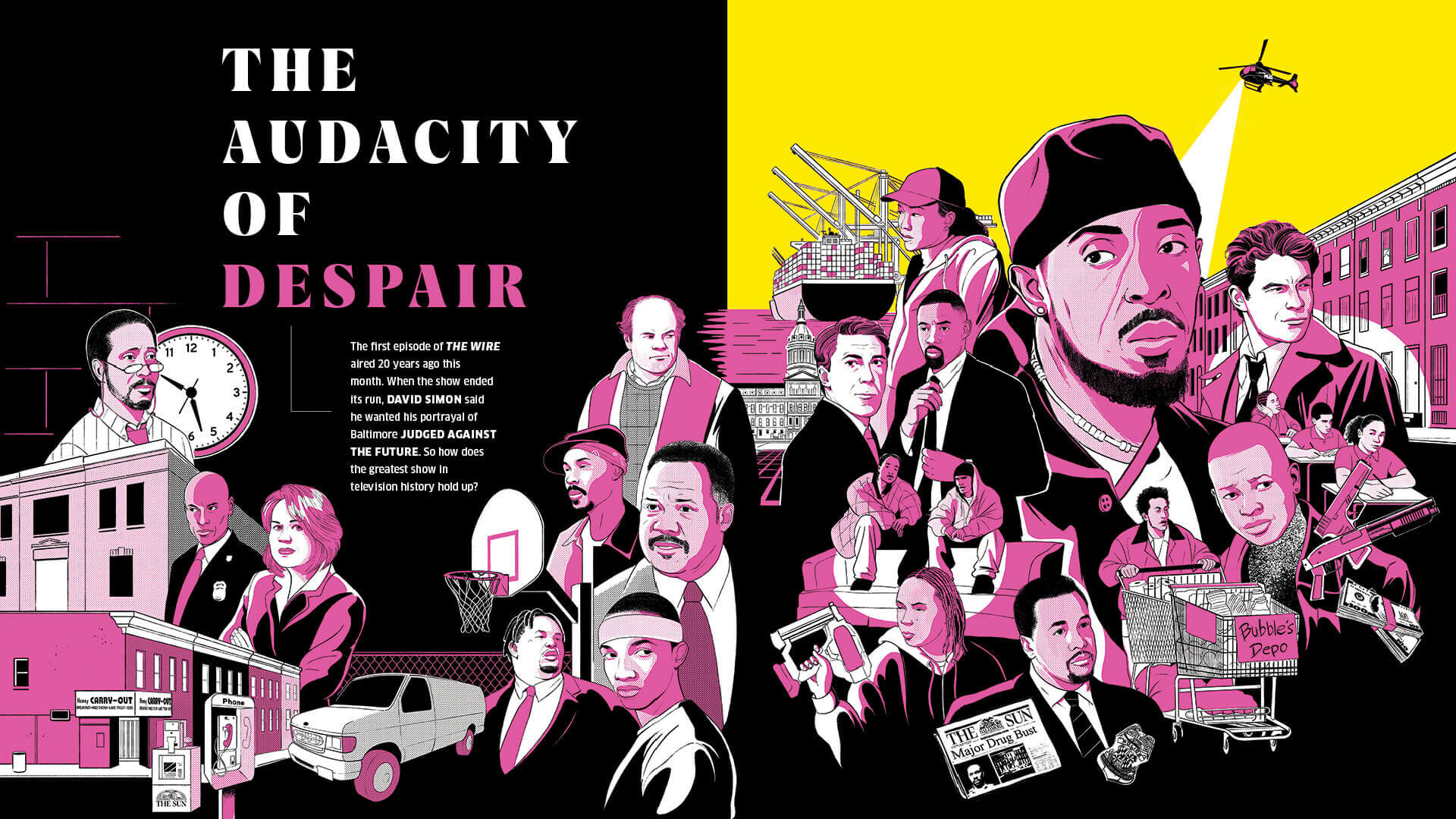

The first episode of The Wire aired 20 years ago this month. When the show ended its run, David Simon said he wanted his portrayal of Baltimore judged against the future. So how does the greatest show in television history hold up?

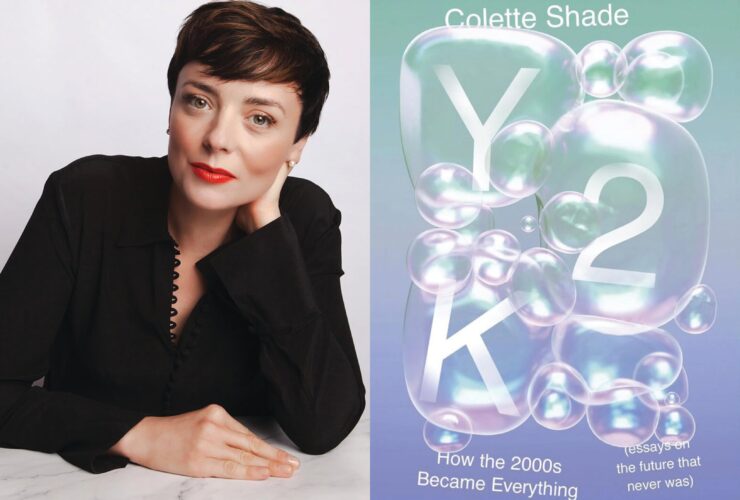

By Ron Cassie

Photography by J.M. Giordano

Illustrations by Alex Fine

“YOU CAN’T EVEN THINK OF CALLING THIS SHIT A WAR.”

“WHY NOT?”

“WARS END.”

—DETECTIVES CARVER AND

HAUK WITH DET. GREGGS.

THE WIRE, SEASON 1

THREE RIVULETS OF BLOOD, illuminated by flashing blue lights, seep from a body lying face-down in the middle of a dark street. In the background: the wail of a squad car siren, the whirl of a helicopter, the howl of a neighborhood dog. A cop picks up a shell casing and places it into a plastic bag. Static voices blurt out from a police radio. Three school-age girls silently take in the scene from their rowhouse stoop. On the steps of a vacant home on the same block, a white Baltimore homicide detective turns to the young Black man seated next to him, bundled in a hoodie and winter coat, blankly staring at his just-murdered buddy.

“So your boy’s name is what?”

“Snot.”

“You call a guy Snot?”

“Snot Boogie. Yeah.”

The cold opening to what many consider the greatest television series ever is a repurposed story David Simon overheard in the back of an unmarked police car in 1988. That was the year Simon took leave from The Baltimore Sun and embedded with a BPD detective unit. The experience produced his acclaimed nonfiction account, Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, which filmmaker Barry Levinson and writer Paul Attanasio adapted for television into a long-running cop procedural. A dozen years later, that reporting (along with another year Simon spent observing the corner of Fayette and Monroe streets in West Baltimore) would also inspire many of the characters and stories he brought to The Wire, including the opening, featuring fictional detective Jimmy McNulty. In fact, that scene and the dialogue, which Simon transcribed almost verbatim, was filmed just blocks from where he had heard the very real Baltimore homicide detective, Terry McLarney, recount the sad story of Snot Boogie’s death. TV critics called it “authenticity.” Simon calls it “stealing life.”

McNulty: “Doesn't seem fair...you know, he forgets his jacket, his nose starts runnin', and some asshole, instead of giving him a Kleenex, he calls him Snot. So he's Snot forever. Doesn't seem fair."

Snot Boogie's Friend: "Life just be that way I guess."

McNulty wants to know who shot Snot Boogie, but any probing queries are shut down. “I ain’t going to no court.” Still, the friend shakes his head. “Motherfucker didn’t have to put no cap in him though.” We soon learn, as Simon had learned from McLarney, that Snot had a habit of snatching the pot from a regular Friday craps game he played in. He received a beating every time he was caught, which was often. Except, this time, someone took it personally.

McNulty, now curious: “If Snot Boogie always stole the money, why'd you let him play?".

Snot Boogie's Friend: "Got to. This America, man."

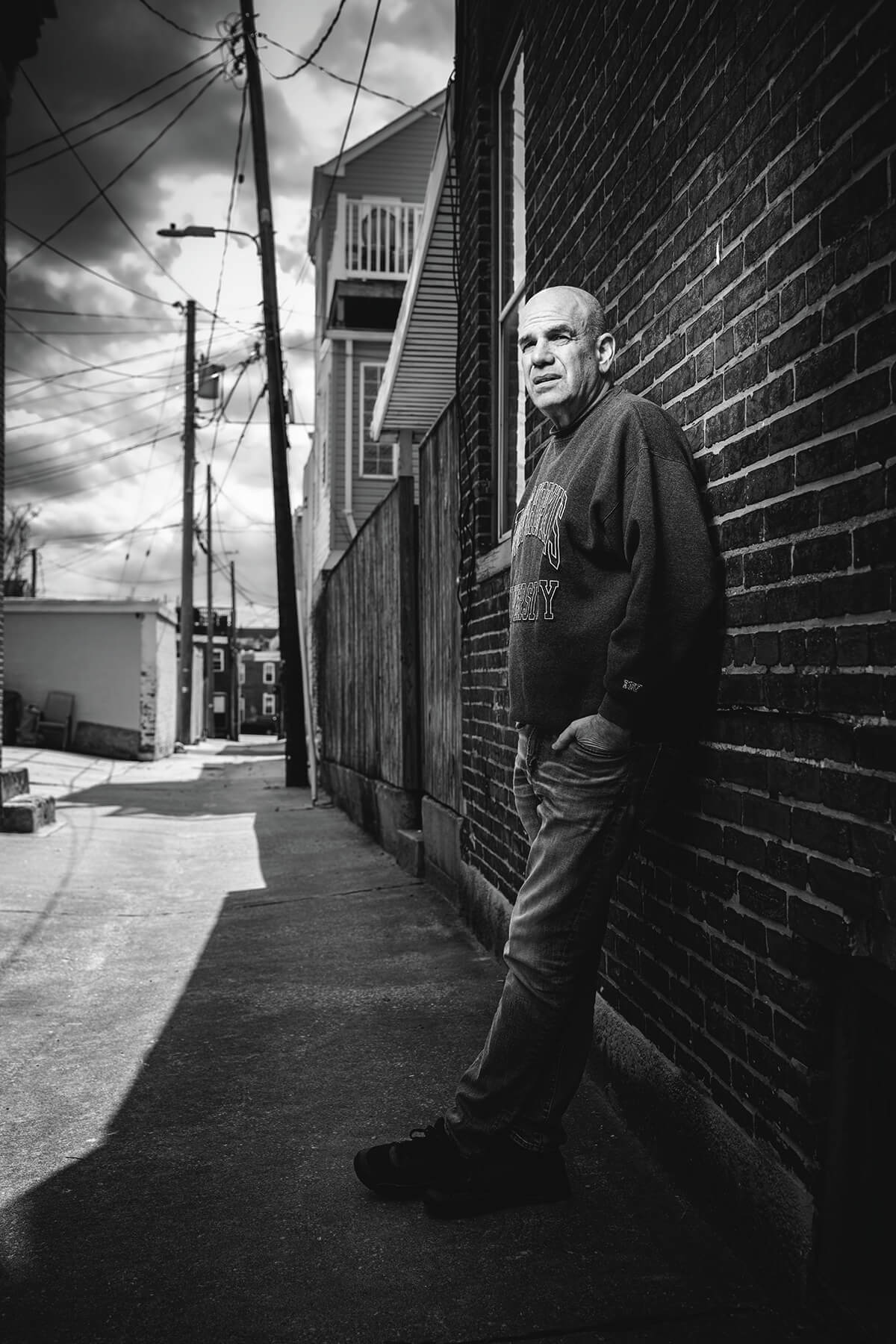

David Simon near his home and office in Balitmore this April. Photography by Mike Morgan

TERRY MCLARNEY HAD laughed as he shared the saga of Snot Boogie’s murder and it seemed almost an afterthought in Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, tucked as it was late in the book. But it stuck with the 28-year-old Simon when he returned to The Sun and began working the police beat again. The words would continue to resonate over time for the still-evolving journalist. “Got to. This America, man.” Simon had joined the big-city daily in 1982 right from The University of Maryland, where he’d served as editor-in-chief of The Diamondback. He wore a ponytail and a diamond earring, indulged in a joint now and then, and his politics were generally those of the anti-Reagan, anti-Thatcher, punk-informed young left of the day. He’d grown up in a liberal Jewish household in Bethesda that believed deeply in the civil rights movement. He had been covering the cops and courts for four years, but he wasn’t necessarily opposed to the War on Drugs when he planted himself inside the homicide unit. Almost no one was. That same year, when former Baltimore Mayor Kurt Schmoke became the first elected official to call for decriminalization and a public health approach to illegal drug use, he was vilified.

THE DRUG WAR IS A HOLOCAUST

IN SLOW MOTION.

— DAVID SIMON

Simon’s follow-up 1997 book, The Corner: A Year in the Life of an Inner-City Neighborhood, which he co-wrote with former detective and future Wire collaborator Ed Burns, was a 180-degree turn from Homicide. As was the Emmy-award winning HBO series, The Corner, which he co-wrote with fellow Diamondback alum, the African-American writer David Mills. Directed by Baltimore native and accomplished ex-offender-turned-actor Charles S. Dutton, The Corner was a depiction of a family in the throes of addiction and a Black community where the promise of living wages—Baltimore lost more than 100,000 manufacturing jobs between 1950 and 1995— had been replaced by opportunity in the drug trade. The show remains a must-watch precursor to The Wire, standing up as a heart-wrenching, deeply empathetic examination of crack cocaine and heroin addiction amid the poverty and decay of a once-thriving, if always segregated, neighborhood.

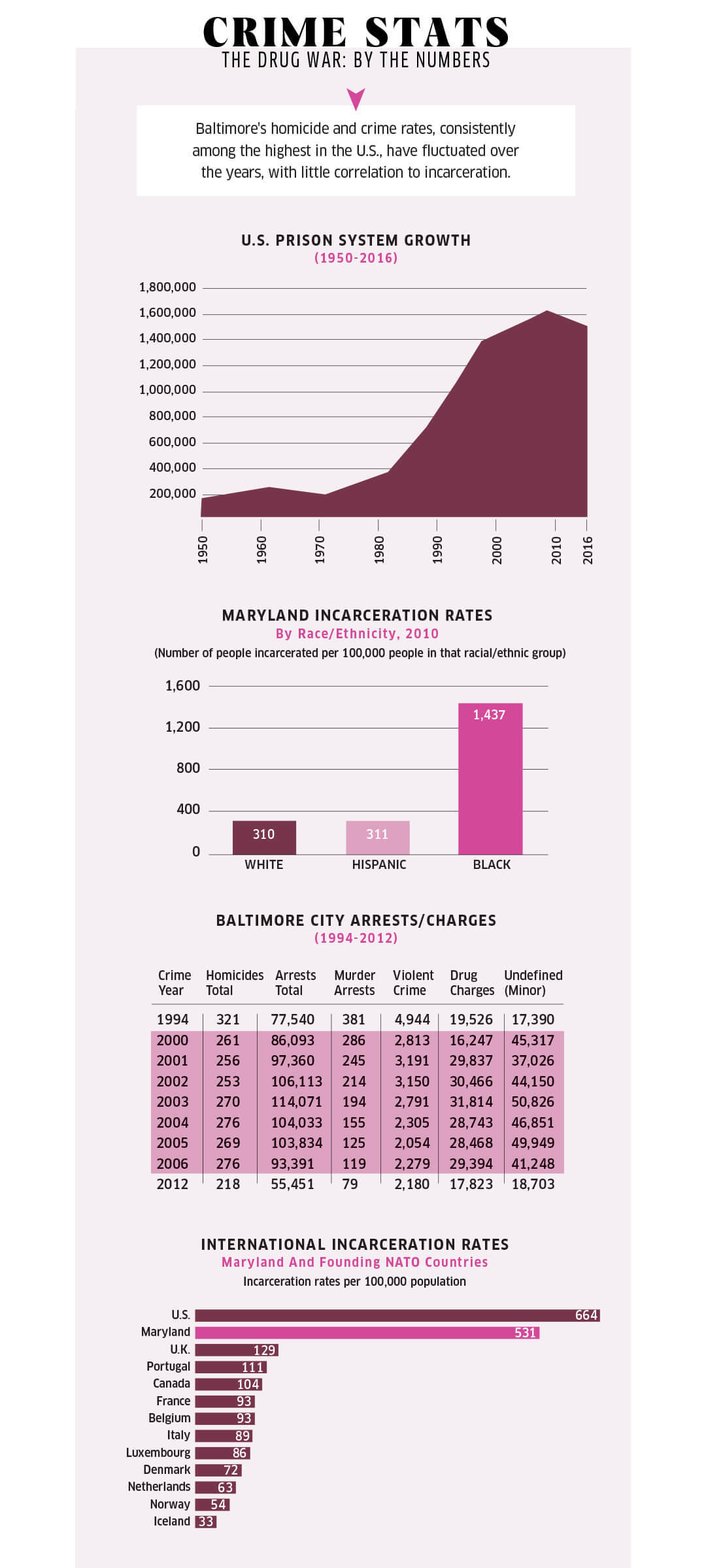

With the success of The Corner, which was filmed in a decidedly non-glamorizing, almost documentary style, Simon’s storytelling ambitions expanded further. Over nearly two decades in Baltimore, he had witnessed the drug war and the incarceration rates metastasize, with the effects causing increasingly more harm than good in the city’s majority-Black neighborhoods. (Reagan announced plans to radically expand the War on Drugs by creating 12 new task force units and hiring 1,200 additional prosecutors in 1982, the same year Simon had arrived at The Sun.) Across The Wire’s five seasons, he folded the brutish futility of the drug war, the bungling BPD, the loss of union jobs, the dysfunction at City Hall, the overmatched public schools, and the decline of the corporate-owned Sun into a broader narrative of failing institutions in a downwardly spiraling city. “All the pieces matter,” the wise fictional Det. Lester Freamon foreshadowed in the first season. As Schmoke had tried to tell those in attendance at the U.S. Conference of Mayors in 1988, and Simon now recognized, America’s drug “problem” was not a criminal issue at its core. It was a public health issue, a policing disaster, and a cruel social justice crisis.

“What drugs have not destroyed,” Simon explained to Salon in an interview 20 years ago this month, as The Wire first hit televisions screens, “the war on them has.”

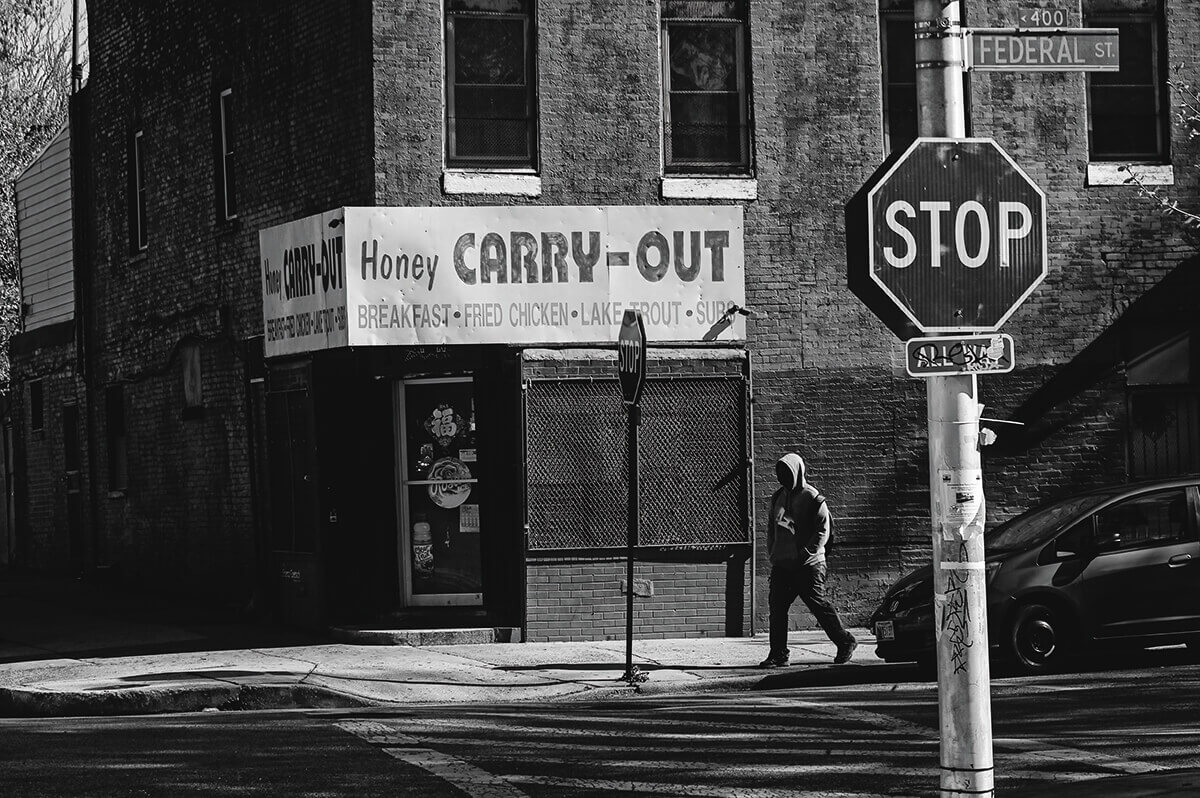

Bodie’s corner: while the original location, the northeast corner of barclay and lanvale, has been torn down, honey carry-out, a half-a-block south, is still a local shop, resembling the infamous season four set down to the red paint.

IN BALTIMORE, specifically, in the early and mid-2000s, Mayor Martin O’Malley and the police department escalated the drug “war” efforts to unprecedented heights. With an eye on the Governor’s Mansion, and, as we came to see, the White House, O’Malley was willing to go to any lengths to bring down the city’s horrific homicide rate and claim even a small victory. The “broken windows” and “zero tolerance” policies that he imported from New York led to a staggering 704,895 arrests during his seven years in office—a figure, incredibly, that surpassed the entire population of Baltimore. (Schmoke, who admittedly had run out of ideas to quell violent crime when he declined to seek a fourth term, did, however, warn there would be fallout from O’Malley's “tough on crime” platform as the then-Councilman campaigned for office.)

WE’RE BUILDING SOMETHING HERE

DETECTIVE...ALL THE PIECES

MATTER.

— DET. FREAMON,

THE WIRE

Tellingly, only 2.6 percent of the arrests made during O’Malley’s tenure represented a violent crime charge. Just another 7.3 percent of arrests represented a property crime allegation. The vast majority of arrests each year, according to Department of Justice data, were listed under “drug abuse”—meaning possession or intent to distribute—and “undefined” minor code violations, the single largest category by far. Additionally, more than 70,000 arrests were made for loitering, disorderly conduct, open container violations, and trespassing from 2000 to 2006. With Central Booking beyond capacity, O’Malley went as far as to push the state courts to install a seven-days-a-week judge at the Baltimore jail intake center to deal with the backup and delays that his policies had created. Each year, tens of thousands of charges were not worth prosecuting, and by 2005, the City State’s Attorney Patricia Jessamy’s office declined to move forward on a full third of all arrests. Worse still, the zero-tolerance policy—which meant clearing corners with loitering arrests— was ruining the BPD’s ability to investigate serious crimes. As overall arrests skyrocketed under the O’Malley administration, arrests for murder, violent offenses, and property crime fell dramatically each year. All this, coincidentally, took place as O’Malley’s doppelgänger, Mayor Tommy Carcetti, was coming to power in The Wire. In fairness, albeit in line with a national decline in homicides, the murder toll in Baltimore had dropped in O’Malley’s first year, but over the next six years, it steadily ticked back up, stubbornly remaining among the highest rates in the country, as it does today.

Charts: Sources from Top: Brennan Center for Justice; Prison Policy Initiative from 2010 U.S. Census; Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Prison Policy Initiative.

In other words, Simon, Burns, and The Wire writing team were scripting the folly and brutality of the drug war in real time: cops pointlessly clearing the same corners, cuffing the same people on bogus charges day after day; interrogating and threatening children and beating people up for no good reason; taking bribes and cash from drug dealers and raking in copious amounts of overtime. All enabled by higher-ups who fudged the stats to prove that the polices were working. Naturally, the supply of drugs, let alone the demand, was rarely interrupted.

But as bad as the Baltimore police department appears in The Wire, the show did not chronicle anything like the number of illegal searches and seizures it conducted, or the endemic lying, false testimony, and wrongful convictions of the era, or the extent of the police department’s barbarism. In the entire five-year run of the series, a single bumbling cop fires his weapon. Yet, as a London reporter who did a job exchange with former Sun, now Banner reporter Justin Fenton in 2009 highlighted—the show was a huge hit in the U.K.—Baltimore police had already shot 16 people, including a 14-year-old robbery suspect, by the time he’d arrived in October of that year.

Afterward, when the show concluded its run in 2008, Simon told local journalist Lawrence Lanahan, in a piece for the Columbia Journalism Review, that he wanted his depiction of Baltimore judged against the future. “What I saw happen with the drug war, a series of political elections, and vague attempts at reform in Baltimore . . . What I saw happen to the Port of Baltimore, and what I saw happen to The Baltimore Sun—I think it’s all of a piece,” he said. The Wire, Simon believed, was about more than even the drug war; it was a snapshot of the decline of the American empire: “Consider it a big op-ed piece and consider it to be dissent.”

The Wire, Simon continued, was a premonition of a darker future, for Baltimore, and by extension, for America—“more gated communities and more of a police state.” Should it come to pass, and if people were to claim no one saw it was coming, he said back in 2008, someone could pull DVDs of The Wire off the shelf and say, “Don’t say you didn’t know this was coming. Because they made a fucking TV show out of it.”

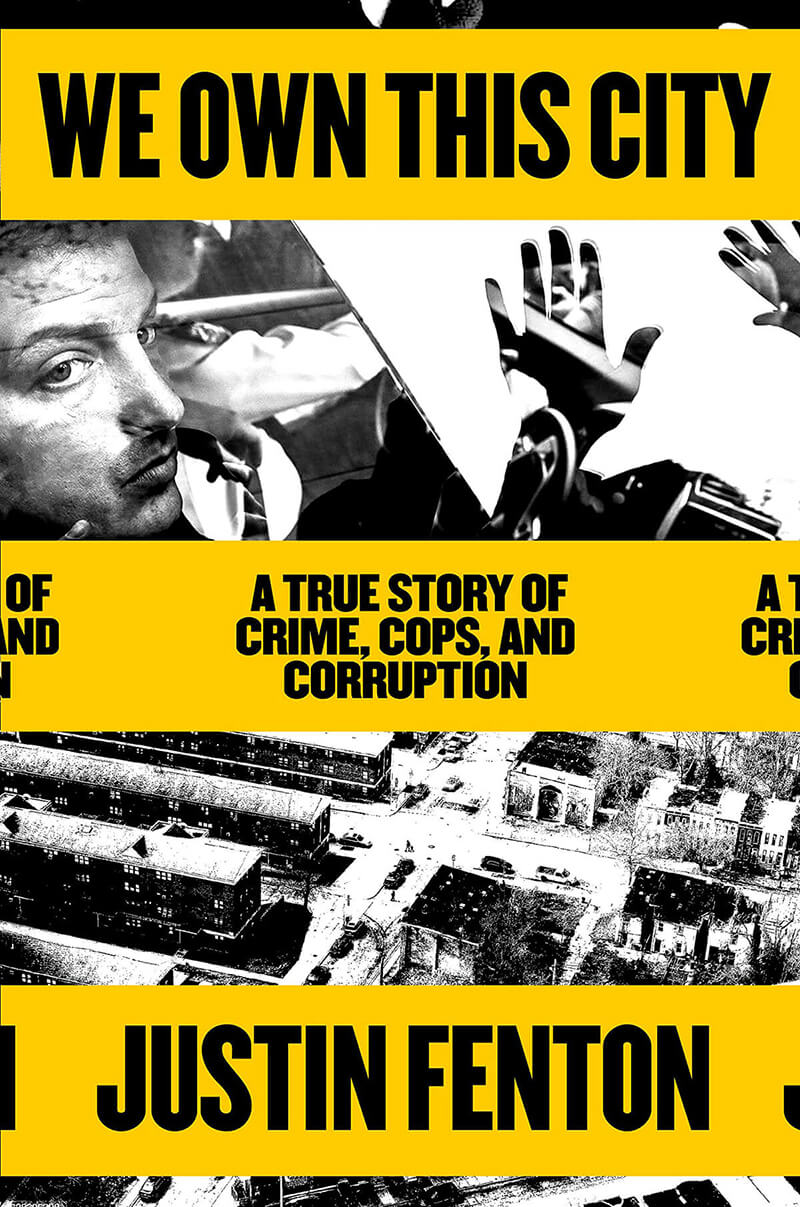

Which raises the question: How has Baltimore fared in the two decades since the city first got a long, hard look at itself on HBO? And how has The Wire held up? If Simon or someone else had another 60 hours to remake The Wire today—not just the roughly six hours he’s given in the new miniseries We Own This City, based on a book by the same name by Fenton on the corrupt Gun Trace Task Force—what would that look like?

Vincent sreet: this tiny pigtown street gave maj. Bunny colvin the idea for “hamsterdam,” a free drug area overseen by sgt. Ellis carver. The area around the fictional “vincent street” is being renovated.

“At the time, I thought, yeah, ‘This is America, this is Baltimore,’ things happen and sometimes you pay the ultimate consequence like Snot Boogie,” says DaJuan Prince, a then-18-year-old production assistant, who played the uncredited role of the Snot Boogie corpse. (“David told me to lie there and keep my eyes open but look dead.”) Prince had grown up in the Lexington Terrace housing project, the real-life “towers” where The Wire’s Barksdale gang controlled the heroin distribution. “The scene wasn’t hard for me to grasp. The whole thing of him stealing the money and still letting him play. I’ve lived on blocks where people stole people’s stashes and came back to actually buy more drugs. They let them, because what can you do about the lost stash? He has money this time so let him just go in and buy the product. Other times, you get caught in the act. Sometimes you pay the ultimate consequence. That’s the game. That’s the way I saw it.

“When I got older, though,” continues Prince, who went on to a career in costume and wardrobe for television and film, including Simon’s new HBO series We Own This City, “I realized it’s only the people on the street level that pay the ultimate consequence [of poverty, of the drug war, and gun violence]. Some people don’t pay any consequence, like the cops, the politicians, the prosecutors, the lawyers. Those are the people getting away with stuff and who are still getting away with stuff.”

THE WIRE CAST

THEN & NOW

After adapting The Corner for HBO (1997), which won three Emmys, and creating The Wire (2002-2008), considered one of the best TV shows in the history of the medium, David Simon moved beyond Baltimore and has become one of the most successful writers and producers in series television. Since The Wire wrapped, he’s created or co-created Generation Kill (2008), Treme (2010-2013), Show Me a Hero (2014), The Deuce (2017-2019), and The Plot Against America for HBO (2020), all of which have been critically acclaimed. Similarly, the cast of The Wire has gone on to rich careers—in some cases, as with Idris Elba and Michael B. Jordan—major stardom. Here’s a brief rundown on some of their subsequent efforts:

Bubbles

Andre Royo has remained busy in both film and television since his memorable portrayal of a heroin addict in The Wire, including playing Thirsty Rawlings in the hit series Empire.

Det. Jimmy McNulty

Dominic West, the English-born actor, earned Golden Globe nominations for his work in The Hour, and for his role as Noah Solloway in the long-running television series The Affair.

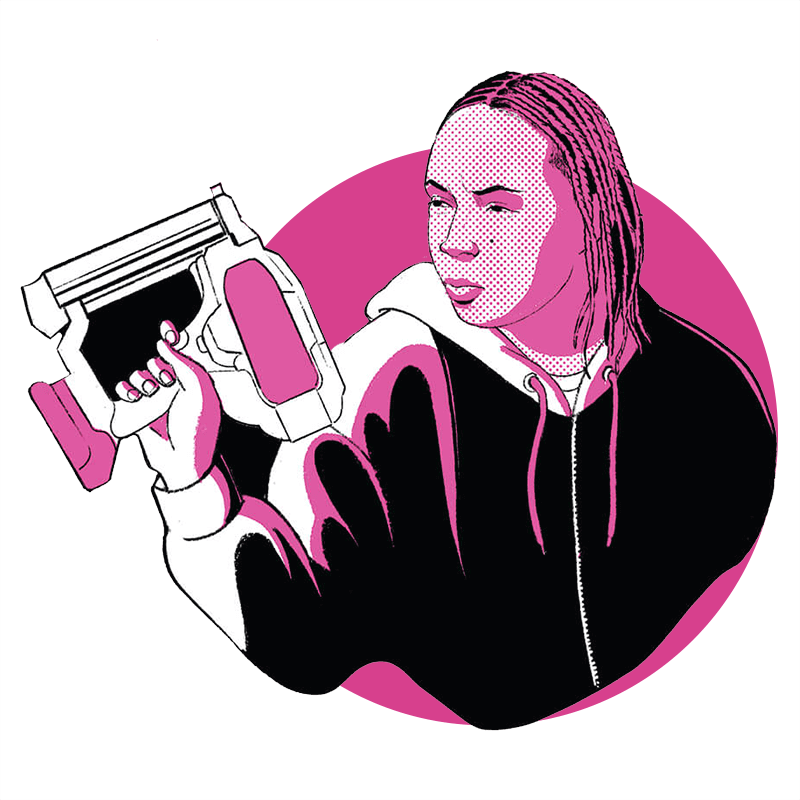

Snoop

Felicia Pearson, the former drug dealer, became an actor after her appearances in The Wire, including roles in Spike Lee’s Da Sweet Blood of Jesus and Chi-Raq.

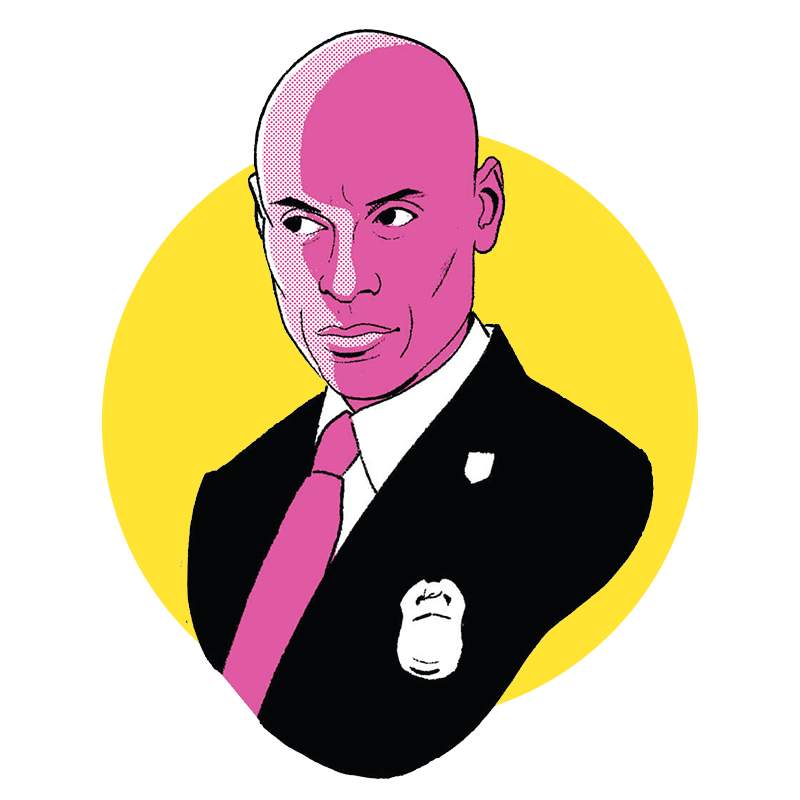

Lt. Cedric Daniels

Lance Reddick, the Baltimore-born actor who was also in The Corner, went on to roles in Oldboy, John Wick, Bosch, and One Night in Miami.

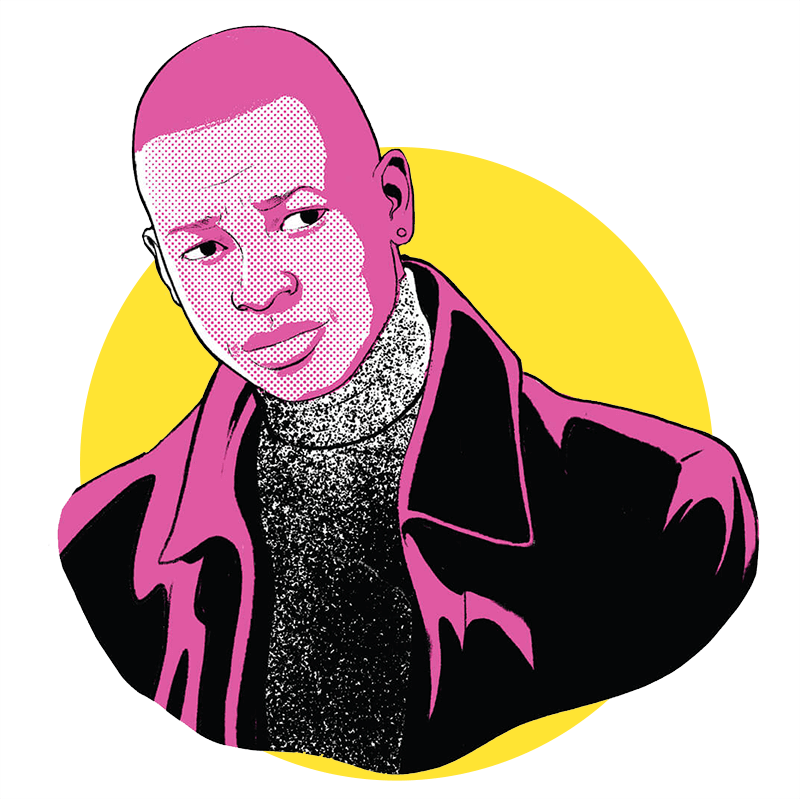

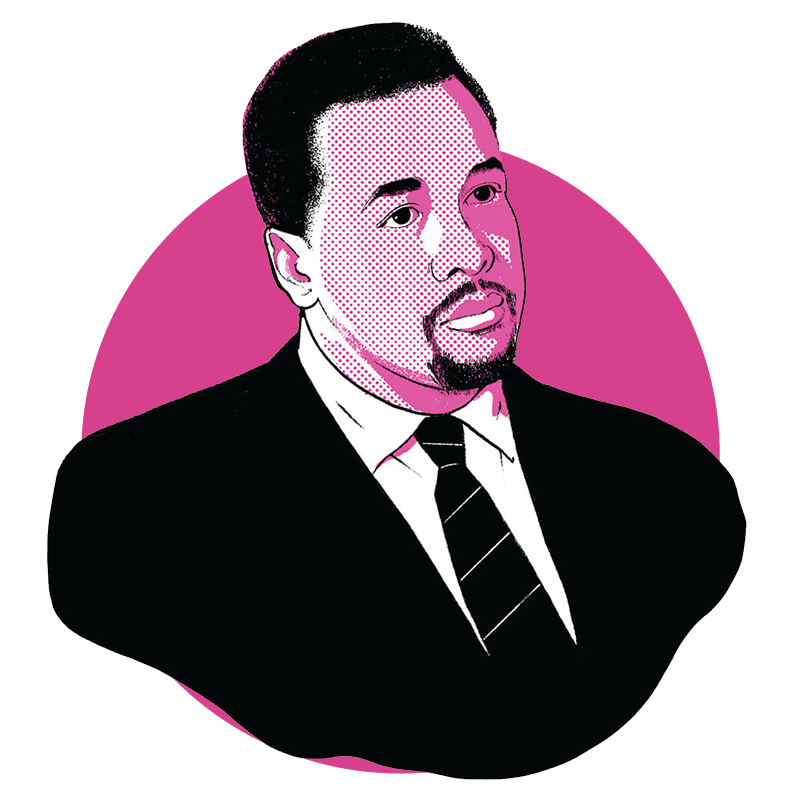

D’Angelo Barksdale

Lawrence Gilliard Jr., who attended the Baltimore School for the Arts, went on to star in The Walking Dead, The Deuce, and the acclaimed film One Night in Miami.

Det. William “Bunk” Moreland

Wendell Pierce, a New Orleans native, played trombonist Antoine Batiste in HBO’s Treme, among many TV, film, and stage projects.

Lester Freamon

Clarke Peters appeared in The Corner before playing the wise detective in The Wire. Among other roles, he starred in Treme and the Spike Lee film Da 5 Bloods.

Stringer Bell

Idris Elba became a major film male lead after The Wire, starring in Ridley Scott’s American Gangster, the series Luther, and Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom.

Herc

Domenick Lombardozzi, who started his career in A Bronx Tale, played Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno in The Irishman, and returned to Baltimore in We Own This City.

Det. Kima Greggs

Sonja Sohn has directed two HBO documentaries, Baltimore Rising and The Slow Hustle, which investigated the death of BPD officer Sean Suiter.

Mayor Tommy Carcetti

Aiden Gillen, from Dublin, has gone from playing the mayor of Baltimore to roles in the films Calvary and Bohemian Rhapsody and the TV series Game of Thrones.

Wallace

Michael B. Jordan, just 15 in The Wire, has become one of Hollywood’s top leading men, starring in Fruitvale Station, Creed, and Black Panther.

Cutty's gym: operated by Dennis “Cutty” Wise, Cutty’s fictional Eastside gym continues to go to ruin 20 years after it was used as a season three set for The Wire.

THE POPULARITY OF The Wire, let alone its cult status, is a strange phenomenon. Critically praised when it aired, the series never won an Emmy and it never garnered anything like the ratings of the show that it is most frequently judged against today, The Sopranos. The epic Italian-American family drama, centered on a suburban New Jersey crime boss, drew more than four times as many viewers on average than The Wire did in its best season and ten times as many viewers as The Wire’s final season.

With its star-making lead performance by James Gandolfini, The Sopranos was easier to follow than The Wire’s sprawling, slowly unspooling saga, which was built around a huge ensemble of largely unknown, if extraordinarily talented, Black actors. (At times, the graphic depiction of heroin use and violence was also simply painful to watch.) Simon had to fight every year with HBO to avoid cancellation, and the show’s fourth season didn’t begin for almost two years after the third season had ended. Ultimately, The Wire became a global phenomenon after it was released on DVD and word-of-mouth began to spread. Podcasts and Facebook and Twitter accounts dedicated to the series abound to this day. It’s an old cliché, but nonetheless true: If you’re from Baltimore, you’ve most likely been asked if the city is really like The Wire when you’ve traveled out of state or out of the country. In March, Russian dissident Alexei Navalny, of all people, when sentenced to an additional nine years in prison, tweeted a quote from show: “Well, as the characters of my favorite TV series, The Wire, used to say: ‘You only do two days. That’s the day you go in and the day you come out.’ I even had a T-shirt with this slogan,” Navalny added, “but the prison authorities confiscated it, considering the print extremist.”

If most U.S. television viewers were not paying attention from the jump, Baltimoreans were, especially those at City Hall. Focused on the perception of the city, as they often are, Baltimore’s elected leaders were not appreciative of The Wire’s portrayal of their fair town. After the first season, then-Councilwoman Catherine Pugh crafted a resolution, initially supported by 12 co-sponsors, called “Let’s Not Just Imagine a Better Image for Baltimore.” The proposed resolution concentrated on the negative references about the city in various reviews of The Wire, and “called for the creation of a committee of volunteers from business and the film industry to create a series of television ads to showcase positive things about Baltimore.”

The ever-combative Simon responded with a letter to then-Council President Sheila Dixon, threatening to change filming locations before the second season. The potential switch, likely to Philadelphia, would’ve cost the city tens of millions of dollars in lost revenue and more than 125 crew-member jobs. Eventually, after phone calls to Council members by Simon and advocates from the Maryland film industry, support for the resolution fell apart. The pushback did not end there, however, and it soon became increasingly hard to tell where art was imitating life and life was intimating art in Baltimore.

After the second season, O’Malley informed Simon that the city wanted “to be out of The Wire business,” while threatening to refuse filming permits. O’Malley was claiming to have reduced crime by 30 percent and demanded to know why the show didn’t highlight the 1,000 more treatment beds that he was funding. (As far as the perception of Baltimore goes, the city didn’t need an HBO series to generate bad press: Dixon was indicted on 12 felony and misdemeanor counts less than a year after the last episode aired, and more recently Pugh was forced to resign as mayor because of corruption charges.)

The Baltimore police got into the act during filming as well, pulling over cast and crew more than once after late-night shoots for no other reason than driving while Black. One of the people victimized was Prince. After picking up 10 police uniforms for the next day’s shoot, he was pulled over for an alleged traffic violation on his way to a small cast get-together in Remington. When the police searched him and then the trunk of the car and found uniforms, they thought they’d hit the jackpot, handcuffing and hauling the wardrobe assistant off to Central Booking. Even after Prince made a phone call to his HBO supervisor, who verified his story and came and grabbed the uniforms, they impounded Prince's car and kept him locked up overnight.

Still, Simon repeatedly tried explain that The Wire wasn’t about Baltimore, per se, or designed to stick it to the city. “Give or take an inside joke or two, these were stories relevant to any number of forgotten places in post-industrial America,” he wrote in an essay in this magazine in 2008. “The problems depicted are profound, complex, and national.”

BEHIND THE SCENES: THE WIRE COSTUME SUPERVISOR

DONA ADRIAN GIBSON

AFTER FASHION school in Atlanta and a union wardrobe gig in local Baltimore theater, designer Dona Adrian Gibson got her television break in The Corner, which won a Primetime Emmy for Outstanding Miniseries in 2000. That led to a long-running job on The Wire, where she rose to costume supervisor for seasons 3-5, and steady work in television and film ever since. From The Wire, the Gwynn Oak native went on to serve as costume supervisor for such series as Army Wives, Treme, The Walking Dead, and She’s Gotta Have It, among other projects. More recently, she served as costume designer for Justified: City Primeval, directed by Michael Dinner and Quentin Tarantino, and We Own This City.

“I had read the book, The Corner, by David Simon and Ed Burns, about a year before getting hired and I really wanted to work on the project and felt like I was fortunate just to get hired as part of the crew,” Gibson recalls. “Then, the first day that I got there, the background costume said to me, literally in the first two hours after I arrived, ‘If you want my job, you can have it. I don’t want it.’ And that’s how my career got started.”

In terms of creating wardrobe, Gibson says, it’s necessary to envision the character in their setting, as well in context with their makeup, props, and dialogue, etc. “I would say you can pretty much identify who a person is when they walk into the room by what they have on, in many ways,” she says. “You know if they’re villainous, if they’re not.” For The Wire, with its massive ensemble—as many as 70 characters overall, and as many as 45-50 characters to outfit in a single episode—the sheer logistics of locating, buying, and making wardrobe was a challenge. And when a specific place—Baltimore in this case—becomes a central character, it brings other challenges, which are generally fun to tackle, Gibson adds. For example, Baltimore’s street fashion changes much faster than, say, trends at City Hall or the Clarence M. Mitchell Jr. Courthouse, she notes.

“One year, all the young guys are wearing the long white T-shirts. There’s the story of the Air Force One basketball sneakers that were popular here and almost nowhere else,” she recalls. “The oversized sweat suits and jeans happened and whatnot. It’s funny, because all that has changed in Baltimore since The Wire, but as far as the way political people dress, that hasn’t really changed that much. Maybe now it will post-COVID? That’s potentially interesting. Street fashion just changes a lot more. It goes through such a quicker evolution than the political class or business class.”

Prop joe’s: a pedestrian symbol faintly resembles a chalk outline in front of Prop Joe’s shop in highlandtown. Now a delicious-looking bistro, the location is surrounded by cuisines from all over central america and mexico along eastern avenue.

THAT SAID, it’s impossible for anyone from here not to take a parochial view of The Wire. More than an inside joke or two, the show leaned into its Baltimore cred. Police commissioner Ed Norris played a homicide detective. Still in the midst of the show’s run, mind you—he admitted to misappropriating up to $30,000 from police funds and was convicted of a felony and fraud. Governor Bob Ehrlich, who was sued by The Sun in 2005 for prohibiting state employees from talking to two of its journalists, took a turn as an Annapolis state trooper. Former Mayor Schmoke got a bit part as the city’s health commissioner, ironically warning the show’s Black mayor he would be vilified as “the most dangerous man in America”—words once hurled at Schmoke—if he went along with a plan to create a de facto decriminalized drug zone in the city. Rev. Frank Reid III of Bethel A.M.E. basically played himself as a politically influential West Baltimore pastor. Columnist Michael Olesker and other journos and ex-journos, including Simon’s wife, the reporter-turned-author Laura Lippman, had walk-on roles in The Sun’s newsroom in season five. Two other ex-Sun newspapermen, Rafael Alvarez and Bill Zorzi, were writers on the series.

A lot of credit for The Wire’s Baltimore bonafides has to go to Pat Moran, a former John Waters “Dreamlander” and an assistant director on his 1972 cult classic, Pink Flamingos. She cast the series, so it’s not surprising some of the most indelible characters were created by professional actors who are also natives. Lawrence Gilliard Jr. played the conflicted middle management dealer D’Angelo Barksdale. Lance Reddick portrayed the ramrod-straight police colonel Cedric Daniels.

Robert Chew, who taught drama at the city’s Arena Playhouse, starred as the colorful east side entrepreneur-kingpin Prop Joe. And who can forget “Ziggy” Sobotka, the weird, immature, drug dealer-wannabe son of the stevedore union leader, played by James Ransone. All went to area high schools.

Then there are “Little Melvin” Williams and Felicia “Snoop” Pearson, who are in a class unto themselves. Williams was a heroin and cocaine trafficker in Baltimore in the 1960s, ’70s, and early ’80s, and someone Wire co-creator Ed Burns had pursued as a Baltimore detective. Williams, who is credited with helping quell the 1968 riots in West Baltimore—such was his status at the time—served as part of the inspiration for the character Avon Barksdale, The Wire’s notorious west side kingpin. He played, however, a charismatic pastor known as The Deacon in the series. The tomboyish and fierce Pearson, who grew up in terrible circumstances, had been convicted of murder at 16. She was discovered at a Baltimore club by Michael K. Williams, the late actor who portrayed the openly gay stickup man Omar Little, who invited Pearson to the set. Her portrayal of the nail-gun toting hitwoman, also known by her real-life nickname Snoop, became one more of the show’s unforgettable characters. Novelist Stephen King called Pearson’s character “perhaps the most terrifying female villain to ever appear in a television series.”

Further below the surface are other uplifting, surreal, and tragic links between The Wire, real Baltimore, and Simon’s and Burns’ work, The Corner. Famously President Obama’s favorite character, Omar is partially drawn from stickup artist Donnie Andrews, who had a heroin addiction and made his living robbing drug dealers. He eventually surrendered himself to Burns for performing a contract killing because it was against his “code.” In prison, Andrews became an anti-gang mentor to younger guys. Following his release, which Simon and Burns had supported, they introduced him to Fran Boyd, the real-life drug-addicted mother portrayed in The Corner, whom Andrews helped get clean and married. (Although there are similarities between Andrews and Omar, the gay aspect of Omar’s character was borrowed from someone called Billy Outlaw, another local stickup artist.) Meanwhile, Boyd’s real-life son, De’Andre McCullough, whose teenage struggles were the central story of The Corner, played the assistant to hitman Brother Mouzone in The Wire. Sharp, observant, and funny—he once told Simon he’d helped him with his research for The Corner because he looked “so out of place that I felt sorry for you”—McCullough died of a drug overdose in 2012. His father had died from an overdose shortly before The Corner aired. At the time of his overdose, McCullough was being sought on warrants related to two armed robberies of pharmacies.

WORLD GOIN’ ONE WAY,

PEOPLE GOIN’ ANOTHER.

— POOT, THE WIRE THE WIRE

The main character in The Wire, of course, is the city itself, which, despite the controversies and anxiety from the powers-that-be, generally embraced the show. Seth Gilliam, who played the young hard-nosed Det. Ellis Carver, said that filming on the streets of Baltimore every day felt like making an independent movie, in a good way, meaning residents often took an interest and became part of the backdrop. The physical locations were obvious to Baltimoreans— the courtyard at the McCulloh Homes housing project, where D’Angelo Barksdale managed the low-level dope dealing from an iconic orange sofa, sits just off Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, mere blocks (and a world away) from downtown. The Port of Baltimore’s Seagirt Marine Terminal starred in season two as fictional labor leader Frank Sobotka fights to get the harbor channel dredged. (Sobotka, by the way, enlists the services of a political insider named Bruce DiBiago, clearly modeled on Bruce Bereano, the real-life lobbyist once convicted of mail fraud, to garner support in Annapolis.) The old Locust Point grain pier, which Sobotka pushes to get reopened, got redeveloped into the Silo Point luxury condominiums a year after The Wire wrapped—a merging of fact and fiction that underscores the opposing trajectories of Baltimore’s working class and the city’s “Gold Coast” white collar professionals. When it came to the rowhouses, vacant and otherwise, the Korean corner stores and storefront Black churches, the dive bars, the slang and accents, the cemeteries, and hundreds of other local references—Faidley’s crab cakes at Lexington Market and Chaps Pit Beef on Pulaski Highway to name two—who other than Baltimoreans could understand their true significance? The actors and portrayals were so good, sometimes Baltimoreans mistook those for the truth, too. There was one time Andre Royo, who played the heroin-addicted character Bubbles, was walking over to the food service area from the set when someone came up to him and said, “They’re giving out free testers,” and handed him drugs. Royo called it his “Street Oscar” moment.

The port of baltimore is one of the country’s busiest ports, and the southeast baltimore waterfront, cranes, and cargo boxes were the landscape in the wire's second season.

Lines between fact and fiction continued to blur. The Ritz Cabaret, the South Broadway strip club— which stood in for the drug dealer-owned money laundering strip club Orlando's in The Wire—was seized by the feds as the HBO series was being shot. The owner of the Ritz was convicted of laundering suspected drug money and hiring illegal immigrants as dancers.

Simon, however, emphasized the show was fiction, comparing it to a Greek tragedy. But he never convinced everyone in Baltimore because so many real people, crimes, and even real homicides are referenced, if obliquely. For example, the killing of three-year-old James Smith III, who was shot while waiting with his mother to get his hair cut at a Pigtown barbershop in 1997, leaving the entire city in grief.

“David Simon isn’t fooling anybody,” well-respected Councilman Kenneth Harris said in 2004. “The Wire is more documentary than it is drama.”

In the end, both sides were probably right. The Wire is documentary and drama. The part of the equation that is troubling for others, is that the show is also entertainment. “I never watched The Wire,” says Ray Kelly, an ex-offender, longtime criminal justice activist, and a founder of the No Boundaries Coalition, which builds community across race, class, and neighborhood in Central West Baltimore. “I wouldn’t dare. I live two blocks from where some of that was shot and watched them film that shit every night. Blatantly imitating what they saw and recording it. Every day. And then they pay actors to portray addicts. So, no, I’ve never seen an episode of The Wire.”

Harris, a 45-year-old father of two, was killed during an armed robbery outside the popular New Haven Jazz Lounge in northeast Baltimore in 2008.

We Own This City

A Q&A WITH CRIME REPORTER JUSTIN FENTON ON WATCHING HIS BOOK ABOUT THE BPD’S CORRUPT GUN TRACE TASK FORCE GET ADAPTED FOR HBO.

BASED ON THE 2021 book by former Sun now Banner reporter Justin Fenton, which chronicled the crimes of the BPD’s infamous Gun Trace Task Force, HBO’s six-episode series We Own This City wrapped May 30. Developed by David Simon and George Pelecanos, and directed by Reinaldo Marcus Green, the series brings the horrific corruption within the Baltimore Police Department to the screen, going back to The Wire era and following the disastrous prosecution of the drug war to the present day.

Former BPD homicide detective Ed Burns and former Sun assistant city editor Bill Zorzi—both Wire alum—joined Simon and Pelecanos in the writers’ room for We Own This City, along with New York Times best-selling author D. Watkins. Also returning from The Wire are numerous actors, most notably Delaney Williams, who portrays former police commissioner Kevin Davis, and Jamie Hector, who portrays former detective Sean Suiter, whose controversial death, one day before he was scheduled to testify in front of a grand jury about police corruption, was ruled a suicide. Baltimore native Josh Charles (The Good Wife) plays former rogue GTTF officer Daniel Hersl. Jon Bernthal (The Walking Dead) is in the lead role as the brutal GTTF leader Wayne Jenkins. Both Hersl and Jenkins, among other Gun Trace Task Force officers, remain incarcerated. Wunmi Mosaku (Lovecraft Country) stars as a composite Department of Justice attorney who led the investigation into the BPD that became the police department’s current operating consent decree with the DOJ.

We Own this city extra.

How close does the HBO series hew to the reporting in your book? There are an awful lot of scenes that are word-for-word, actual dialogue. Some of that is from wiretap conversation, and [other dialogue] somebody said to me in an interview, or it’s something that was said at a press conference. Certainly, there are other scenes that we know, generally, what happened from different participants, but we weren’t there in the room with a microphone recording. And then, there are other characters who are sort of a mashup of different people...but it’s all rooted in real-life events.

The series goes back to the start of Wayne Jenkins’ career in the early and mid-2000s. The show, to my delight, tracks with the book. It does not just catch up with these guys in 2015, 2016, while they’re robbing people. It jumps back to Jenkins and his career choice, and back to 2003 when he’s a rookie—what he’s being told to do and what he’s observing in others about how the department works.

David Simon had suggested that you write a book based on your Gun Trace Task Force reporting. He follows what is going on in the city and at some point I met him, probably in 2009. We’ve been in touch occasionally, but yeah, he contacted me during the trial. I’m a newspaper reporter. I’m trying to think about what my next story is going to be, what my week is going to be, and maybe how I can tell this in a narrative format for the paper. He said there’s interest from HBO [as the GTTF crimes were unfolding]. I know George Pelecanos was interested, and he said, you need to write a book and we’ll option it.

What do you think Baltimoreans will take away? I hope that Baltimoreans, who experienced this [criminal behavior from the police department], feel validated, and there’s some perspective on how the police department works and doesn’t work. Hopefully, it’s illuminating. There are people who think this stuff doesn’t happen or can’t happen or people are lying [about being victimized by police]. You know, we just need to support police without any reservation. This is a look at what was happening right under our noses, all the time.

Read our full conversation with Fenton, here.

Silo point: the renovated grain elevator is virtually unrecognizable. Silo point played an integral role in the wire’s season two, which focused on the city’s white working class.

TWENTY YEARS AFTER The Wire’s premiere, we have a clearer view of the War on Drugs and its effect on Baltimore. If Simon wanted his groundbreaking series to be judged by the future, it has proven prescient—if anything, it didn’t go far enough. And why has Baltimore been so particularly victimized by the War on Drugs? To put it plainly: Because Baltimore is a hyper-segregated, majority-Black city, whose low-income, redlined, under-resourced Black neighborhoods have been both target and battleground of the 50-year war.

In her 2010 book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, civil rights litigator and law professor Michelle Alexander documented how racism was always at the heart of the War on Drugs. From her research, Alexander found that incarceration rates have little correlation with crime rates, which have fluctuated since Richard Nixon first coined the term “the war on drugs” a half-century ago. National crime rates were in fact at a low point in 1982 when Ronald Reagan first escalated the crusade.

The sun: the dark portals of the former baltimore sun’s building on calvert st., now ironically home to the bpd’s central district offices. In season five, the paper came under fire for writing about a fictional “serial killer” created by det. Jimmy mcnulty to boost homicide numbers.

Since the early 1970s, the incarcerated population in the U.S. has quintupled, with two million people in jail and prison today, far outpacing population growth and crime. Although the U.S. has five percent of the global population, it holds more than 20 percent of the world’s prison population. It’s been driven by the drug war’s focus on urban, lower-income communities of color, longer and racially disproportionate prison sentences—100 to 1 for crack versus powder cocaine, for example—parole revocations for non-violent drug offenses, and record police, prosecution, and prison spending. Those factors have not only led to the highest rate of incarceration in the world, but also a grossly disproportionately rate of imprisonment for Black men.

“It is no longer socially permissible to use race, explicitly, as a justification for discrimination, exclusion, and social contempt,” writes Alexander. Instead, the U.S. utilizes the criminal justice system to label Black and Brown people “criminals” and then “legally” discriminates against ex-offenders in almost all the ways it was once legal to discriminate against African Americans prior to the civil rights reforms of the 1960s. In a city that’s nearly two-thirds Black like Baltimore, with thousands of returning citizens each year, the practice is crippling for ex-offenders, but also for our majority-Black communities as a whole. “Once you’re labeled a felon, the old forms of discrimination— employment discrimination, housing discrimination, denial of the right to vote, denial of educational opportunity, denial of food stamps and other public benefits, and exclusion from jury service—are suddenly legal,” Alexander adds. Once a convicted felon, “you have scarcely more rights, and arguably less respect, than a Black man living in Alabama at the height of Jim Crow.”

Nationally, one out of every three Black male children born today can expect to go to prison in his lifetime, according to the ACLU, as can one of every six Latino boys—compared to one of every 17 white boys. This is despite the fact that illicit drug use and drug dealing are basically equal across ethnicities. One study in Maryland found that while white people comprised the majority of Marylanders in drug treatment, African Americans represented 90 percent of the state’s drug prisoners. Similarly, a 2020 ACLU research report revealed that although Black people represent a little more than 60 percent of Baltimore City’s population, between 2018 and 2019, 96 percent of all marijuana possession charges were filed against Black people in the city.

THEY FUCK UP, THEY GET

BEAT. WE FUCK UP. THEY

GIVE US PENSIONS.

— DET. CARVER, THE WIRE

Ultimately, the drug war destroyed what little trust remained in Baltimore between the Black community and the BPD, especially after the 1968 riot. In the early and mid-1960s, following outrage over police brutality—and a damning two-year investigation by the International Association of Chiefs of Police—the sitting Baltimore police commissioner was ousted. His replacement, Donald Pomerleau, who had consulted on the investigation, described the BPD at the time as “the most corrupt and antiquated in the nation, and had developed almost no positive relationship with the city’s Negro community.” Two decades before, there had been a massive uprising in the city against police brutality after a white officer killed an unarmed Black soldier on leave from Fort Meade, and it wasn’t until the end of the 1950s that the police department began to integrate.

The corruption and police brutality simply never ended. In 1973, there were at least six different city, state, and federal investigations into the police department. In January of the same year, in a brazen theft that would’ve made the GTTF officers in We Own This City blush, some 1,250 bags of heroin, worth an estimated $100,000, went missing from the Baltimore police department’s evidence control room. (Also in the 1970s, Black officers founded the Vanguard Justice Society, to represent their rights and interests, and help Black officers move up the chain of command.) By 1980, the NAACP had again called for a federal investigation into police brutality, and it wasn’t until 1984 that then-Mayor William Donald Schaefer appointed Bishop Robinson as Baltimore’s first Black police commissioner.

Meanwhile, the 515-page outside report commissioned by the city and released earlier this year, “Anatomy of the Gun Trace Task Force Scandal: Its Origins, Causes, and Causes”—essentially the backstory of We Own This City, Simon’s current HBO series about the BPD—makes it difficult to imagine a golden age of Baltimore policing ever existed.

Jenny Egan, chief attorney in Baltimore’s Office of the Public Defender, says improvements have been made in the police department since the signing of the consent decree with the Department of Justice in 2017. That the General Assembly decriminalized small amounts of marijuana in 2014, and that the overall number of arrests in the city are way down, is significant, she says. There are miles to go, however.

“There is so much left to be done if you look at that report, and no one in the City Council or state legislature has talked about addressing the rampant problems of false testimony by police, that police officers regularly and routinely lie, according to the report,” says Egan. “Their whole job is to testify under oath and to tell the truth right off. I don’t understand how any of those arrests or convictions are viewed as legitimate by any stakeholder in the system, given the report.”

So, yes, 20 years after The Wire launched, Simon’s premonition of a darker future for the city has proven all too true. In Baltimore, the drug war and mass incarceration became something akin to a jackhammer pounding away at our de facto segregated and under-served Black neighborhoods. ("Simon has historically framed the drug war as a war on the underclass, not as intentionally racist policy, while readily recognizing its disproportionate impact. In a 2021 tweet, he acknowledged: “The drug war is racist in its origin, its execution, its maintenance and its intent and purpose.”)

Per capita homicides in the city, which jumped after the death of Freddie Gray from injuries sustained in police custody and the subsequent uprising, have risen from 37 per 100,000 in 2002 to more than 57 per 100,000 today—the second highest in the country behind St. Louis. Drug and alcohol-intoxication deaths, which were falling during The Wire’s run, have exploded from 152 in 2008 to more than 1,000 last year, driven by the prescription opioid epidemic and the poisoning of the heroin supply by the deadly synthetic drug fentanyl.

Meanwhile, despite the dramatic reduction in arrests, there remains an extraordinarily high number of people still in prison, Egan notes, including from the O’Malley years. At the same time, overdose deaths don’t receive anything like the attention given to gun violence, even though drugs are a potentially preventable public health crisis. “When we think about overdose deaths versus murders today, which they outnumber 3-1 in the city, we don’t seem to get the same sort of ‘crisis’ headlines,” she says. “Isn’t this what a War on Drugs was supposed to be about?”

In fact, inequality in the historically segregated areas of the city that Morgan State University public health professor Lawrence Brown coined the “White L” and the “Black Butterfly” has significantly widened over the past 20 years.

The city’s overall poverty rate has remained consistent over the past two decades, at just over 20 percent. But only because poverty has been falling in gentrifying, formerly working-class white neighborhoods as fast as it’s been climbing in the many Black neighborhoods in Baltimore. In the “White L,” poverty fell dramatically from 2000 to 2014-18, in neighborhoods including Canton (from 11.5 percent to 4.3 percent), Woodberry (13.6 to 5.6), and Locust Point (9 to 4.1).

Over the same period in the “Black Butterfly,” poverty shot up in Johnston Square (19.6 to 49.1 percent), Harlem Park (34 to 50.6), and Sandtown-Winchester (43.3 to 50.8).

“We’ve started to coin the phrase ‘enduring divergence,’” says Seema Iyer, who oversees the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance at The University of Baltimore’s Jacob France Institute. “Some neighborhoods are getting everything, and some neighborhoods are continuing to atrophy month after month. That becomes self-reinforcing. The neighborhoods that grew in population and the neighborhoods that lost population between 2010 and 2020 are basically the same neighborhoods that grew and lost population between 2000 and 2010. It’s not random. There is a clear pattern.”

Today, the themes of a series like The Wire would no doubt be different. Arrests in Baltimore, which peaked at 114,071 in 2003, had fallen by 56 percent to 50,314 by 2014—at least in some part due to a 2006 lawsuit brought by the ACLU and NAACP. In 2019, the last pre-COVID year, the number was down to 20,100, and in 2020, to 14,022.

Edward tilghman middle school in season four played off the name of the real tench tilghman elementary/ middle school, Which sits almost on the edge of patterson park.

Police violence, in the age of smartphone videos and the Black Lives Matter movement, would likely be front and center. Earlier this year, Baltimore police shot and killed an unarmed 18-year-old driver named Donnell Rochester who was wanted on outstanding warrants. Wrongful convictions would also likely be front and center. Several real-life detectives from Homicide and The Wire have seen decades-old cases fall apart, as a New York magazine article recently documented. Since 1989, 25 men convicted of murder in the city have been exonerated, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. In 22 of those cases, official misconduct was present. “The history of BPD officers and detectives withholding exculpatory evidence from the accused, coercing and threatening witnesses, fabricating evidence, and intentionally failing to conduct meaningful investigations is decades long,” wrote attorneys for Clarence Shipley, a Baltimore man who spent a quarter of century in prison for a murder he was exonerated of in 2018.

Safe consumption sites for hard drugs to reduce overdose deaths might replace the “Hamsterdam” decriminalized zone of The Wire. The futility of the BPD’s drug corner “street rips” might switch to the current focus on illegal gun possession. The increase in Hispanic immigration and subsequent ICE policing was something Simon said he would’ve addressed with the next season of The Wire, had he been given six seasons. City Hall corruption, the influence of developers—i.e. the Port Covington tax break—those things would just need an update.

Having grown up in West Baltimore in the ’70s and ’80s, Lawrence Gilliard Jr. remembers what it was like coming back to the city to film The Wire in his role as D’Angelo Barksdale. “All the communities where we shot, when I was a kid, were vibrant communities with kids playing and neighborhoods flourishing,” Gilliard recalls. “We lived at Franklin Square, although I played Little League football for the Lexington Terrace squad, and I remember traveling to the McCulloh Homes neighborhood to play. They all had recreation centers, and kids were out in the street game playing in the summertime.”

After having lived in New York for many years, the city looked vastly different when he returned to shoot the show. “I would hear from my family and my younger siblings, who were still in Baltimore, about how things were changing over the years. I’d go back to my neighborhood, too, and I could see it declining.

“The way drugs were pumped into the communities, that played a big part of breaking down communities, breaking down working households,” Gilliard continues. “But the War on Drugs, which broke down communities further, it was a false war, in my opinion. That was a made-up thing.”

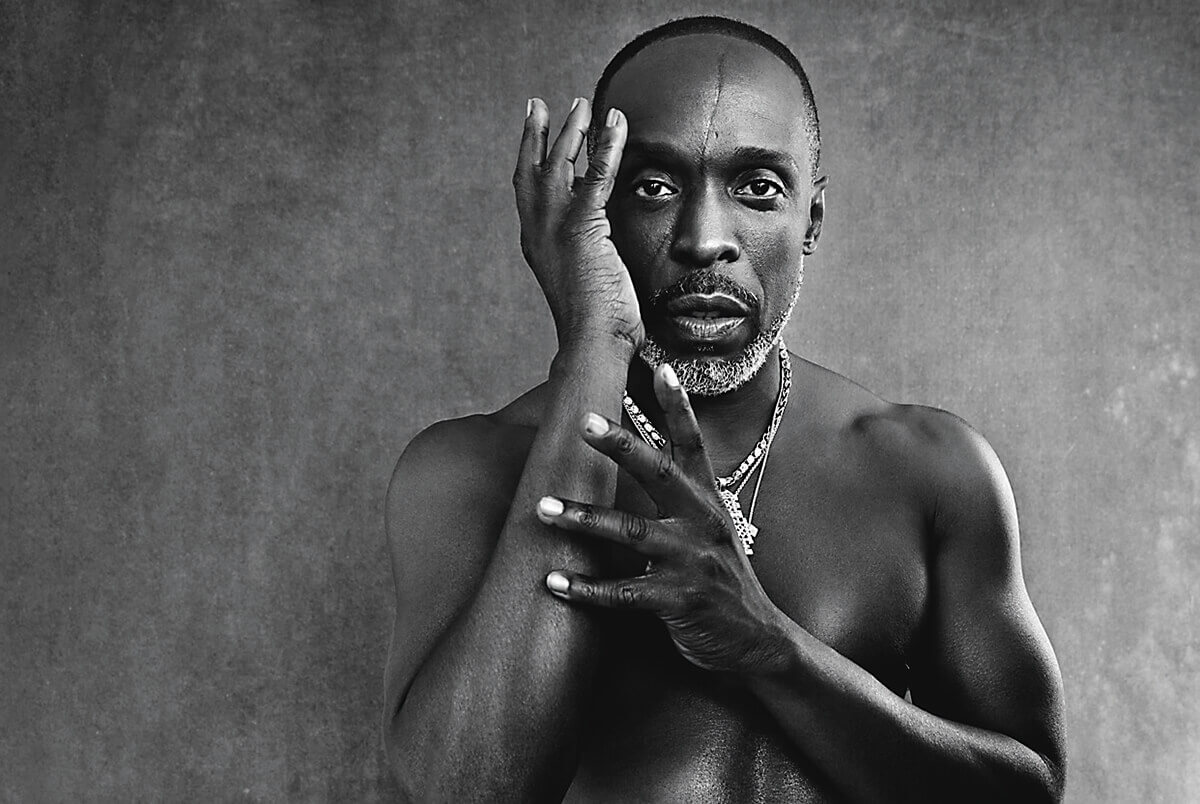

MICHAEL K. WILLIAMS

(1966-2021)

Photography by Jesse Dittmar

WHEN THE BELOVED actor Michael K. Williams died of an overdose last September, the loss was deeply felt among fans across the country, but especially in Brooklyn, where he was born, and in Baltimore, which he considered a second home. And, of course, the loss was acutely felt among his Wire family. Williams worked mostly as a dancer until a bar fight on his 25th birthday left him with a long, distinctive facial scar—the result of being slashed with a razor—that changed the course of his career. He soon was being asked to audition for “thug roles,” he told NPR, eventually landing the role of Omar Little, the fiercely loyal, openly gay, heavily armed robber of drug dealers—the most memorable character in what many consider the greatest television show ever.

“AN IMMENSELY TALENTED MAN... PORTRAYING THE LIVES OF THOSE WHOSE HUMANITY IS SELDOM ELEVATED UNTIL HE SINGS THEIR TRUTH.”

“He was fearless, he was outspoken. He suffered not even a little bit from social acceptability. He didn’t care what anyone thought about him, except the ones he loved,” Williams said of Omar in a 2020 GQinterview. “And he had a huge moral compass, and he wasn’t afraid to express it. I was the complete polar opposite. I was frightened a lot of times growing up. I had a very low self-esteem and a huge need to be accepted. The only thing I knew that I shared with Omar was his sensitivity and his ability to love, and his ability to love deep. I knew that I had that in me.”

After The Wire, Williams’ star kept rising despite recurrent troubles with drug addiction that at times had also been a problem during his breakthrough portrayal of Omar. He went on to roles in numerous award-winning television shows and films, including the HBO biopic Bessie, the Netflix series When They See Us, and most notably, the long-running HBO series Boardwalk Empire, where he starred as Chalky White. He earned five Emmy nominations before his death at 54.

“The depth of my love for this brother, can only be matched by the depth of my pain learning of his loss,” Wendell Pierce, who played Det. “Bunk” Moreland in The Wire, posted on Twitter after Williams’ death. “An immensely talented man with the ability to give voice to the human condition portraying the lives of those whose humanity is seldom elevated until he sings their truth.”