Arts & Culture

The Next Stage

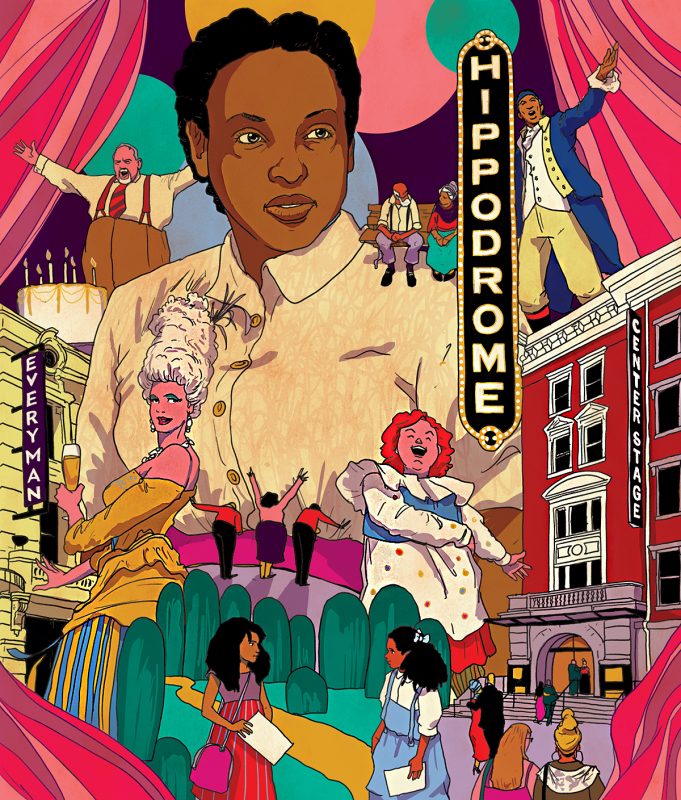

Baltimore’s theater companies are working toward a more active, inclusive future.

A quick turn down the hall from the Hippodrome Theatre’s Fayette Street side entrance reveals a strange sight for visitors to Baltimore’s base of operations for glitzy Broadway tours. Open double doors reveal two stories of windows pouring sunlight over long-hidden marble and steel beams, and pieces of the walls and floor seem to be missing. It’s hard to place what exactly what was there before. Were these doors always here? Did the building always go this far?

Take the time to look over a couple of project boards posted at the entrance and, if you’ve spent some time around the theater, it clicks. These walls were once a funny shade of tan, right? And those windows weren’t always so big, were they? No, they definitely weren’t. The space was once the France-Merrick Performing Arts Center’s ballroom, closed off to most and open only during special events (more than a few Best of Baltimore parties, for example).

The M&T Bank Pavilion, as the ballroom is officially known, was originally built as the Eutaw Savings Bank around 1881 and has been part of the France-Merrick Performing Arts Center since the adjacent buildings were acquired by the state of Maryland in the 1990s. But the building has sat mostly unused for the past 15 years, and now work is finally underway to follow through on the original plans for the space: to turn it into a new venue, one that could be a gateway for audiences of all ages and stripes to interact with the Hippodrome in a whole new way.

Once complete, this historic space will be home to a 25,000-plus-square-foot flexible performance space that will expand the nonprofit Hippodrome Foundation’s ability to present shows, events, and educational programs, in addition to hosting cultural institutions around the city and providing them with a place to perform without the struggle of lugging or renting technical equipment. The new space will also allow the foundation to run its free camps and workshops for Baltimore-area schoolchildren year-round instead of only during the summer when the Hippodrome stage is free.

The expansion is just one of the forward-thinking projects currently underway among Baltimore’s theaters. There’s something stirring behind the scenes in the local theater community—and in many ways, the Hippodrome and theaters like it are taking their cues from their smaller, more experimental brethren. To be clear, there are still plenty of chances to bring the family to a classic retelling of Romeo and Juliet or a Disney musical, but there’s a radical streak running through the rehearsal halls and stages across the city, one that’s hoping to bring people back into their dimmed halls by exploring new voices and lending power to those who need their voices amplified.

In some ways, that streak has been around for ages, inspiring storytelling in neighborhoods across the city. In Fells Point, The Vagabond Players, one of the oldest continuously operating community theaters in the country, has been sustained by actors volunteering time and energy beyond the responsibilities of their daily lives to bring drama to its audiences for more than 100 years. Downtown, the African-American community theater company Arena Players is nearing its seventh decade in Baltimore, having first sprung up at what was then Coppin State College a decade ahead of the Black Arts movement elsewhere in the country.

There’s something stirring behind the scenes in the local theater community.

Then there’s the wealth of independent theaters and companies throughout the city—groups like Baltimore Theatre Project and Charm City Fringe and Spotlighters and Iron Crow—that have consistently been exposing city audiences to diverse works and new types of performances. This year alone has brought artist-owned performance space Le Mondo to a long-awaited home on Howard Street, marked color-conscious theater troupe ArtsCentric’s move to a permanent home in Remington, and sent experimental troupe Single Carrot Theatre away from its marquee and into new corners of Baltimore in hopes of “activating different neighborhoods in different parts of the city that may be less seen,” according to artistic director Genevieve de Mahy.

But, now, as we roll toward a new decade, the city’s larger companies have caught up as well. The Bromo Arts District, home to Everyman Theatre, The Hippodrome, Le Mondo, Arena Players, and several other venues, is abuzz, and there’s talk among this tight-knit group of creative leaders of bringing new voices to new audiences. They want to engage with people in new ways, encourage a new generation of theater-goers, and sate current audiences’ appetites for more diverse and inclusive works.

Just how to tackle all those goals is the question of the hour for Baltimore’s theaters, and its creative community in general. How do these cultural stewards reach out to people and get them to engage with the art they’re producing? Part of the answer is producing stories that are more representative of the diverse world in which we live. At Center Stage, that means highlighting works by women, people of color, and LGBTQ playwrights and reexamining the way they work with artists. The same is true at Everyman, where founding artistic director Vincent Lancisi is using this new season to blend classics with highlights from the current “golden age of female playwrights.” The theater is gambling on the idea with its biggest season ever, eight total plays, four of which are written by women and three of which, including the premiere of the final play in Caleen Sinnette Jennings’ Queens Girl trilogy, are part of the first-ever New Voices Festival. The festival will also launch an intimate new upstairs space.

“There’s a renaissance of playwriting and women authors out there. How long have we been suppressing this? We just haven’t seen them because they haven’t had opportunities and see the light of day. . . Now the opportunity has presented itself,” Lancisi says. “Let’s take the best of the best famous plays, pay homage to those who came before us, but let’s create a lot of opportunity for some of these new voices to be heard. The world is changing faster than we care to recognize or are even able to keep up with, and the theaters have to catch up.”

With greater representation and dedication to wider populations, there’s hope that, like it has during so many eras before, the theater can become a gathering place and center of education and activism. It’s the reason why socially conscious Single Carrot left the stage and started scouting spots to bring their immersive performances to new neighborhoods. And it’s the idea that compelled the folks from Center Stage to bring a truck bearing an invitation to Miss You Like Hell, a “joyful musical about an undocumented mother and her U.S.-born daughter” to the September meeting of GOP leaders in Harbor East because, as they explained, they thought the House Republicans would find the play “illuminating.” Escapism, this is not. As Center Stage puts it, they want to meet audiences where they are.

When new director of artistic partnerships and innovation Annalisa Dias joined Center Stage this summer, she put that intention into action by meeting with both local independent theaters and social justice organizations with the aim to better understand the work already being done in the city to engage audiences and connect them to resources. One such meeting was an education event hosted by Guerrilla Theatre Front’s Dogs of Art that covered immigrant rights, ICE detentions in Baltimore, and how people can help. The event helped inspire programming for Miss You Like Hell, for which Center Stage created a lobby installation that offered information on direct service providers working with the local immigrant community.

“We’re going to start opening these doors and really trying to activate the space in a new way,” Dias says. “It’s trying to rethink the experience of walking through these doors and going to a show and what you do before and after. How do we make this a space where people want to hang out and interact in a different way?”

For many companies, that “meet people where they are” mentality extends to area schools. Giving students the opportunity to experience drama and see themselves reflected in it is a common thread among the leadership of the city’s theaters both big and small. Whether it’s introducing school groups to the Bard at Chesapeake Shakespeare Company or building and performing an in-class puppet show with Black Cherry Puppet Theater, these troupes are finding ways to connect kids to the performing arts and hopefully start a lifetime of participation in the city’s creative landscape. Partnerships between the Hippodrome Foundation and the Baltimore Design School have even opened up theater as a career path by offering older students interested in costuming opportunities to learn from area professionals and network with local costume warehouses that work with national productions.

Student matinees at theaters across the city feature talkbacks with casts and crews, and students often say these class visits are the first time they have ever seen a professional production, a trend Everyman’s Lancisi has seen grow over the past decades.

“Sadly we’ve lost entire generations [of theater-goers] to date, and we like to say it’s because of price, but I think it’s also because of theater-going traditions,” Lancisi says. “It always requires somebody or some place to provide the exposure. The first time that the students come and see a play can be a life-altering experience for them. They see themselves on stage, or represented in some way, or their point of view matters when they’re encouraged to talk to us about it and react out loud as a community together.”

“The world is changing faster than we care to recognize . . . and the theaters have to catch up.”

Making the younger generations a part of this community is one of the keys to Baltimore theaters’ broader vision for the future, but the hope is that new voices and experiences will be the siren songs that bring people both young and old back into the theaters, away from streaming at home and back downtown. And once those audiences are in the seats, that they’ll engage with all the little things that add to the experience —local art inspired by the shows on the walls, chances to discuss work with the cast, interactive elements of the performance itself —but also with one another.

“[Center Stage] could be activated as a space where people really want to gather and unpack and process, a fun, joyful space of healing, resistance, power-building, democratizing. . . all these things,” Dias says. “We have power to change the way things have always been done and uplift and amplify artists who are living in the city.”

And as these spaces expand and diversify, the whole community benefits. More so than some other industries, there’s a feeling of camaraderie and support among Baltimore’s creative class. The larger venues are inspired by experimentation and new ideas coming from the smaller companies, and smaller companies can be assisted by the resources of the large as each inspires its audiences to seek out more from the wealth of options around it. The Hippodrome Foundation has already been in talks with 56 groups, including local concert series, art spaces, and other theater companies, about using their new state-of-the-art location once the renovation is complete.

“There are 70 arts organizations that don’t have permanent homes. We want to be the incubator for the growth that’s happening,” says Ron Legler, president of the France-Merrick Performing Arts Center. “What we’re hoping to do is take some of the smaller things that are out there that are gems in the city and help them grow and help them find different revenue sources to stay competitive.”

That growth and support means bringing works and performers to new audiences, and giving those audiences what has always worked in the theater, stories that connect and contribute to the conversation. If successful, they have the power to change the way people think and feel. It’s a big ask, but Baltimore’s casts and crews and creative leaders are willing to do the work. They’re used to doing things the hard way.

“The best case scenario for me has never changed, which is that all the theaters of Baltimore are full of audiences hungry for the work they’re doing, that their marquees are bright, that they’re reaching a wider audience, a more diverse audience, that people are willing to try new things or go to a theater they’ve never heard of before,” says Lancisi. “Doing things live is the most labor-intensive and challenging thing to do, but we do it because it’s magic. There’s nothing like it. You’ll have a communal experience, and it’ll just blow you away.”