Arts & Culture

The Little Theater That Could

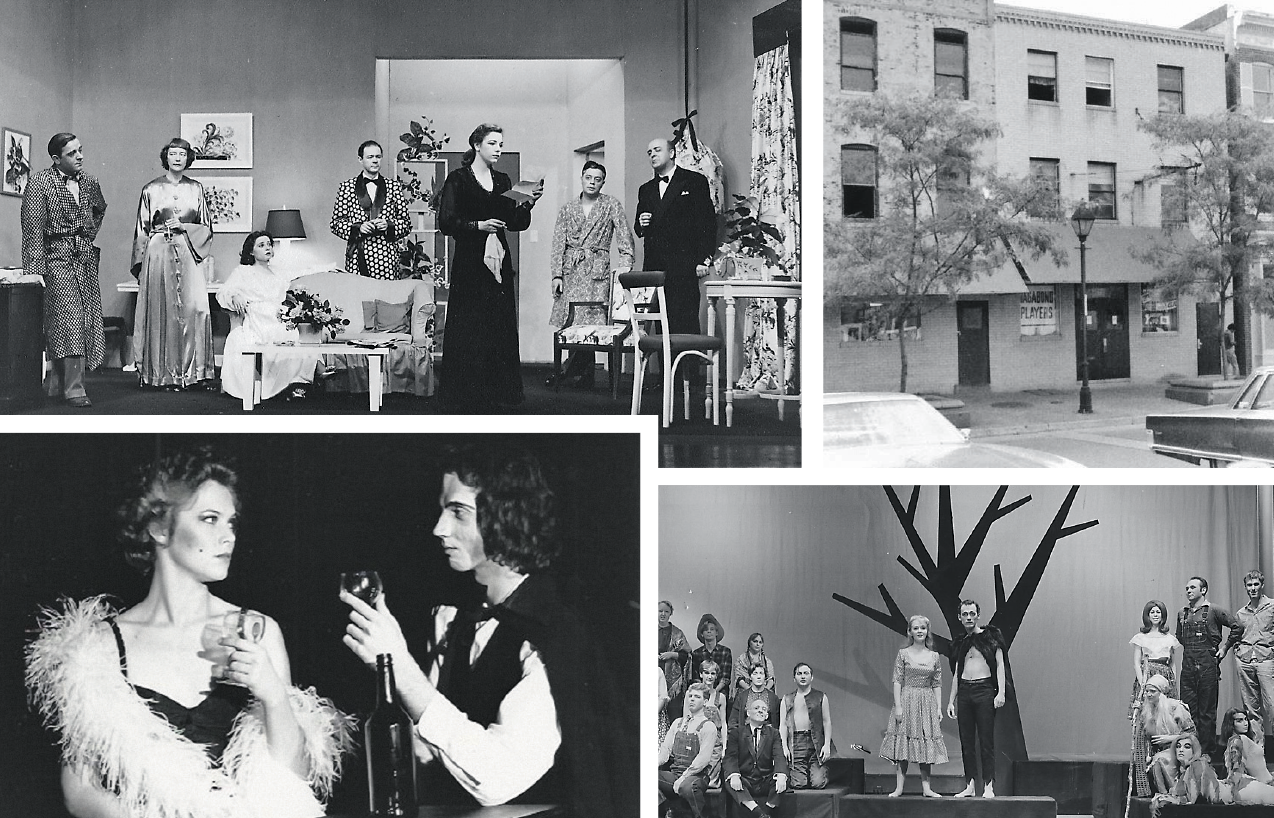

Vagabond’s first century includes literary icons, the occasional Hollywood star, and local theater devotees.

Carol Evans sits on a couch in the lobby of Fells Point’s Vagabond Theatre and places a large Jim Beam bottle on the floor beside her. After something of a dramatic pause, Evans nods toward the bottle. “It’s a prop,” she says, smiling.

Its contents, indeed, appear more like apple cider than bourbon, which makes sense, because Evans, a Vagabond Players board member dressed in a navy blue sweater and slacks, looks more like a theater dame than raging partier. That said, she notes that the building used to house a tavern—Corral’s Bar—before Vagabond settled here in the 1970s. In fact, during a 1973 production of Tennessee Williams’s Small Craft Warnings, which is set in a bar, a sailor wandered in during the show, walked onto the set, and tried to order a drink.

Evans chuckles at the story, one of many colorful tales that circulated during this past season, which marked Vagabond’s centennial and gives it bragging rights as “America’s oldest little theatre.” Literary icons such as H.L. Mencken, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Eugene O’Neill figure into that history, alongside a multitude of mostly unheralded actors, directors, set builders, lighting designers, costumers, and sound techs.

Last year, MD Theatre Guide readers voted Vagabond “Best Community Theatre,” though Evans prefers calling it “non-equity” theater. Vagabond’s directors and actors do not get paid, but technical workers receive a small stipend. It’s an approach that “lets us showcase the tremendous talents of local, everyday people,” Evans says.

“You need dedication . . . and continuity to maintain a successful theater.”

As if on cue, one of those locals appears at the door, hauling a piece of furniture on his back. Evans springs from her seat to open the door, and Greg Guyton enters, slightly bent under the weight of a maroon and gold divan, which will be used as a prop in the next show, Moon Over Buffalo. Rehearsal begins in an hour, and Guyton plays one of the leads. “We make our actors do all the work,” he says, heading toward the stage. “The production is on our backs.”

He’s joking, but not really. Most Vagabond principals wear various hats. Besides being a board member, Evans is co-producing Moon Over Buffalo, handling publicity, and acting in the show. When asked about the producer’s responsibilities, she quips, “We make sure everything gets done.”

Plus, they all have day jobs: psychologist, orthopedic surgeon, bakery manager, or Ph.D. candidate. Evans is a retired educator.

“We’re all really hard workers,” she says. “You need that sort of dedication, leadership, and continuity to maintain a successful and solvent theater, which we’ve done for 100 years.”

The Vagabond history can be traced back to a spring night in 1916, when three theater enthusiasts were waiting for a streetcar outside the old St. James Hotel at Charles and Centre streets. (The hotel has since been razed.)

Carol Sax, head of The Maryland Institute College of Art’s design department, was chatting with New Yorker Constance D’Arcy Mackay, who was in town to spearhead an event commemorating the 300th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, and Adele Gutman Nathan, who acted with a touring theater troupe. They got talking about the Little Theatre Movement—which then popularized non-commercial, more experimental theater around the country—and agreed that Baltimore had enough homegrown talent to support such a scene.

Sax noticed a “For Rent” sign in the window of the hotel’s ground-floor storefront. Looking through the window, they saw an empty space, two-stories high. At the far end of the room, a raised platform looked like a stage, which they took as a good omen. The next morning, Sax returned to the St. James and paid $19 for the first month’s rent.

Sax and Nathan took the reins, recruited other supporters, and, with the help of Sax’s Maryland Institute students, transformed the vacant shop into an intimate theater. They chose the Vagabond name because it implied artistic independence and freedom.

“At the very beginning, the Vagabonds were what we might call today an ‘alternative’ theater,” says Evans’s husband, Tim, who is also a board member, actor, and the group’s unofficial historian. “It was a revolt against the traditional theater of the 19th century.”

The theater opened in November 1916 with the players performing one-act plays (usually three or four per night). The inaugural program of three short plays included Mencken’s The Artist. It was a biting satire set during a classical concert, with the thoughts of a German pianist and his audience substituting for traditional dialogue. Basically, the critics snooze, the men ogle the women, and the women swoon over “the great pianist,” who ruminates over Beethoven, the shortcomings of America’s women, and the gastrointestinal eruptions caused by all the beer he has consumed. Overall, Vagabond’s debut received positive notices, with one review noting that the stage “was but little larger than the kitchenette of the modern apartment.”

Vagabond’s second lineup of shows included Eugene O’Neill’s Bound East for Cardiff. That summer, Nathan had paid a visit to the Provincetown Playhouse, where she was impressed by several plays and paid $15 a piece for the manuscripts, including O’Neill’s, on the spot. It was the first time the playwright, who went on to win Pulitzer and Nobel prizes, was paid for his work. In addition to O’Neill, Vagabond would also introduce the city to new works by the likes of George Bernard Shaw, J.M. Barrie, August Strindberg, and Anton Chekhov.

Though The Sun noted that O’Neill’s play was not well received in Baltimore, Vagabond’s first season—infused as it was by local talent and quality work—proved to be a resounding success. Back in New York, Constance d’Arcy Mackay, in her 1917 book about the Little Theatre Movement, wrote prophetically, “The Vagabond Theatre expresses the native art impulse of Baltimore. It does not rely on outside forces but draws its forces from within, a thing that makes for permanence and stability.”

The 1932-1933 season (by then, Vagabonds was mounting full, three-act productions) included what is arguably the most infamous play in the theater’s history, a production involving F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, who were then living in Baltimore. Written by Zelda, Scandalabra was, according to one critic, “a bizarre mix of supernatural characters and drawing room witticisms” that ran a whopping five hours long. At the premiere, the curtain reportedly rose at 8:15 and didn’t drop until after one o’clock in the morning. By 1:30, Scott was working through a case of beer and cutting the script to half its original length.

The 1932-1933 season involved F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.

Upstairs at Vagabond, amidst a jumble of props and costumes, Carol Evans points out the chair Fitzgerald sat in as he worked through the night. Preserved all these years, it has become somewhat mythic, a totem from Vagabond’s storied past. “It actually looks like a throne,” says Evans, before noting that Fitzgerald’s efforts were mostly for naught.

The critics had attended opening night and were merciless in the next day’s papers. The play flopped.

Over the next few decades, Vagabond weathered not only the occasional box office disaster, but also fallout from the Great Depression, World War II, competition from the film industry, and relocations to venues that included an old stable on West Monument Street, a carriage house on Read Street, and the basement bar at what was then the Congress Hotel on Franklin Street. Its prospects were, at times, tenuous, but the group fought hard to keep the doors open.

But the theater benefited mightily from enduring leadership by Helen Penniman and John Bruce Johnson. They virtually led the troupe through its first 80-plus years. Penniman, who joined the board in 1917 and retired as board president in 1961, resisted calls for the theater to turn professional and never wavered from a commitment to local talent. Johnson joined as an actor in 1960, presided over the board for 30 years, and oversaw Vagabond’s move to its current home in Fells Point. He also helped solidify its brand of programming—innovative and popular plays with an occasional edgy production in the mix—before retiring in 1998. Johnson’s 2008 obituary in The Sun said friends dubbed him “the patriarch of community theater in Baltimore.”

A white porcelain urn containing Johnson’s ashes sits on a desk in the theater’s upstairs office. “He’s always with us,” says Carol Evans.

Vagabond (lovingly called “Vags” by actors and theater devotees) transitioned away from its experimental roots, as public tastes and the local theater scene evolved over the years. The advent of Center Stage, Everyman Theatre, Theatre Project, and smaller groups such as Single Carrot Theatre amply filled the niche for new and challenging work. Though there have been memorable exceptions since Vagabond settled in Fells Point—like when John Waters’s colleague Steve Yeager wrote and directed a Freudian take on Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde that included a young Kathleen Turner in 1976—the theater’s programming is decidedly mainstream, which provides the revenue needed to remain open. “At this point, we try to present shows that we know people want to see,” says Evans.

A porcelain urn containing Johnson’s ashes sits in the office. “He’s always with us.”

With that in mind, a board committee invites proposals from directors and maps out each season, generally a mix of a few comedies, one or two serious dramas, and a musical. For its centennial last season, Vagabond culled favorites like Our Town, The Lion in Winter, and Moon Over Buffalo from past seasons. The coming 2016-2017 season will include Neil Simon’s The Odd Couple, Arthur Miller’s All My Sons, The Complete History of America (abridged), and Avenue Q, the Tony-winning musical.

In addition, a 100th anniversary celebration is scheduled for Oct. 16 at Admiral Fell Inn, and the theater will host a commemorative staged reading of O’Neill’s Bound East for Cardiff on Dec. 7, exactly 100 years after it played at Vagabond.

Preparations are also underway for the next century of shows at Vagabond. The theater lobby was recently remodeled and new bathrooms were installed. This summer, the auditorium’s carpet and 104 seats are being replaced. The seats currently being used are mid-1970s hand-me-downs from the old Morris A. Mechanic Theatre. “We’ve certainly gotten a lot out of them,” says Evans, who points out that, these days, they are usually filled by a mix of Vagabond regulars, younger folks from the surrounding Fells Point neighborhood, and out-of-town visitors.

Evans stops speaking, as the sounds of clanging swords and stage fighting shouts of, “Hah! Hah!” drift upstairs from the stage below. In a few minutes, she’ll be needed onstage.

Rehearsal for Vagabond’s next show has begun.