The latest chapter in the saga of the murder of Hae Min Lee and conviction of Adnan Syed for the crime came to a close last night with the finale of HBO’s The Case Against Adnan Syed, which director Amy Berg and her team worked on for three-and-a-half years.

Through interviews, research, and a team of private investigators and experts, Berg has constructed a solid argument for Syed getting a new trial, if not his innocence. Before the final episode, “Time is the Killer,” aired on HBO, the Landmark Theatre in Harbor East hosted a premiere of the finale featuring a panel discussion with Berg, attorney C. Justin Brown, and former Baltimore City prosecutor Ivan Bates, moderated by Marc Steiner.

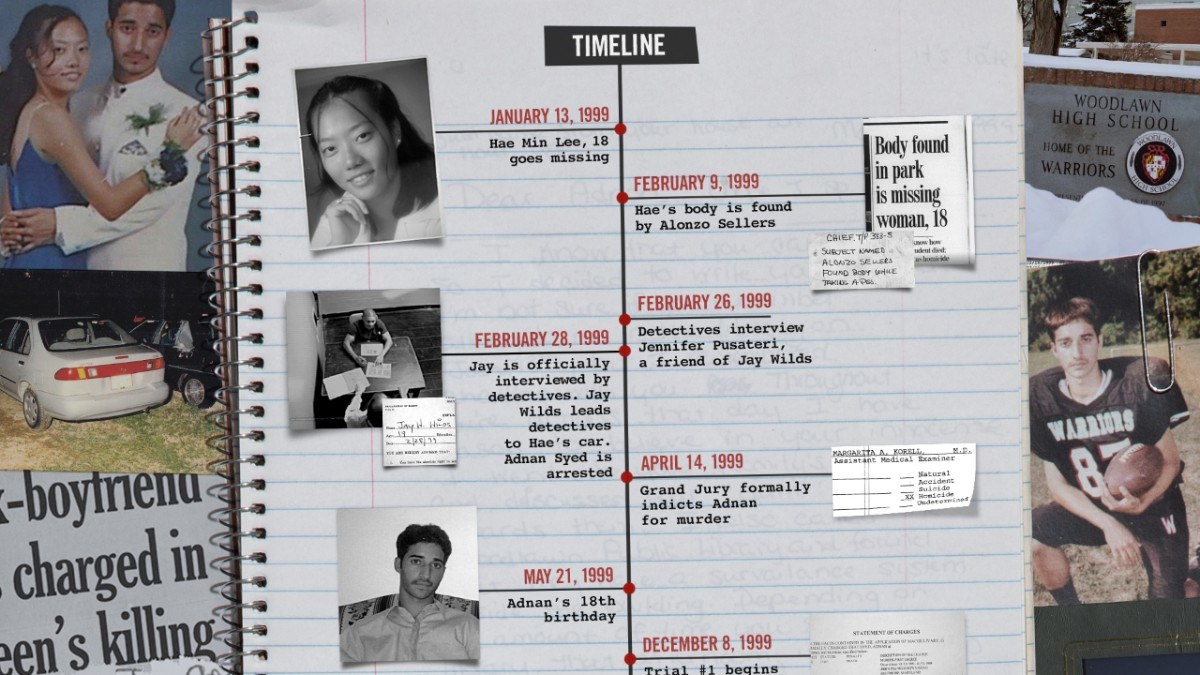

For those attempting to keep track of the twists and turns of a case that has now stretched across 20 years, here’s some of the key points we learned from the finale and post-show panel. Many, many spoilers ahead.

The fingerprints

Fingerprints left on Hae Min Lee’s car did not match Syed, or anyone else whose prints are in the system. This means whoever they belong to has never been booked by law enforcement.

The autopsy

Fulton County, Georgia, medical examiner Jan Gorniak examined the autopsy report and other details regarding Lee’s body and posited that she may have been somewhere other than Leakin Park for eight to 12 hours before she was buried. This change in the timeline is based primarily on a phenomenon called “lividity” during which blood settles in the body differently depending on how it is positioned.

Jay Wilds’ testimony

Wilds declined to be interviewed for The Case Against Adnan Syed, but according to Berg, when they spoke he discussed several points that contradict his previous statements (Wilds has contradicted himself many times before), including that the police coached him to say that he first saw Lee’s body in the parking lot of Best Buy and that Syed had asked him to provide 10 pounds of marijuana, which Syed then allegedly used to blackmail Wilds into helping bury Lee’s body.

Hae Min Lee’s car

Turf physiologist Erik Ervin’s testing and analysis of the grassy area where Lee’s car was parked was not conclusive. But Ervin did state that, based on the freshness of detritus on the tires and the turf below it, he believed the car had been there for a week at most. This hypothesis is supported by interviews private investigators hired by Berg conducted with a longtime resident of the area where the car was parked.

What comes next

The series ends with the March 8 ruling in the Maryland Court of Appeals that reinstated Syed’s conviction, meaning that his hopes for a new trial are on hold for the moment. But this is not the end of Syed’s legal fight.

“Other courts have found ineffective assistance of counsel when an attorney fails to contact an alibi witness who was neutral and who provided an alibi for the time of the murder. So it was absolutely stunning to us that Maryland is now the outlier on this issue. We did not see that coming,” said Justin Brown following the March 28 premiere at the Landmark.

When asked where completing the series has left her, Berg also stated her surprise over the ruling. “I mean, we expected to be in a different place tonight, so it’s hard to kind of imagine,” said Berg. “This turn kind of casts a dark light on the story. So, we’re not done obviously.”

The same day the finale premiered in Harbor East, the results of DNA tests mentioned in the film were also released. Several pieces of evidence previously went untested, partially due to concerns from the defense team that Syed’s DNA could be present Lee’s car or on her person because they had remained friends after their breakup. “If anyone has been holding it back, it has been me, because I have been concerned that it could potentially be misinterpreted,” said Brown. “But finally an opportunity arose to do it.” None of the recovered evidence contained DNA matching Syed’s.

Brown said that the team would go as far as the Supreme Court to try to get Syed his new trial and was met with a roar of applause from the packed theater, which included the filmmakers, Syed’s legal team, Rabia Chaudry, Syed’s friends and family, and many of those interviewed for the documentary series. Brown followed with another promise.

“If the Supreme Court doesn’t hear it, then we’ll try to go to federal court, and if the federal court doesn’t hear it, we’ll go back to Baltimore City Circuit Court, and we’ll keep going,” he said. “As long as we have support, as long as we believe in Adnan and we believe in his innocence, there’s no reason we’re going to stop.”