Be

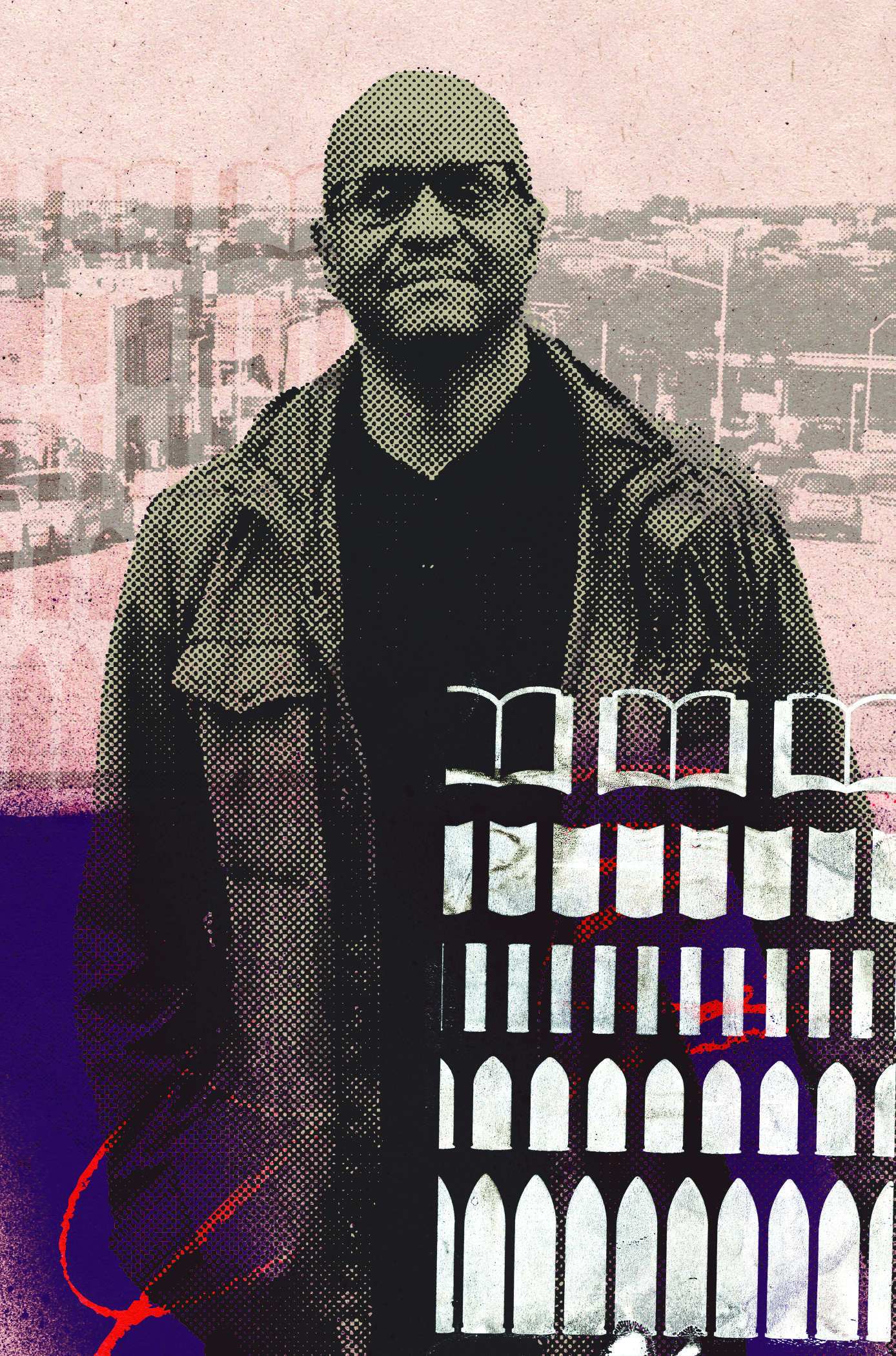

Author and Mental Health Advocate Kevin Shird on Baltimore’s Need for Accessible Trauma Care

"I know firsthand the impacts of trauma and stigma on one’s decision-making and how it has hindered communities of color from seeking treatment and counseling," writes Shird, who survived street violence and prison with the help of therapy. "I want to help tear down those barriers."

One day, I was sitting in my living room eating barbecue Pringles and working on my first book, a memoir of my life as a drug dealer, when a torrent of unexpected emotion rose up. I remember it like it was yesterday. I’d just started recounting the details of a shootout in broad daylight that I’d been involved in with a member of a rival crew decades earlier.

As I wrote about the unnerving incident, it struck me, for the first time really, just how incredibly dangerous and reckless that situation had been. Years had passed since that day, but I had buried the memory until I started writing. Putting it on paper ripped open the scab on that old wound and revealed something I hadn’t thought much about.

Our brains have a way of pushing traumatic memories into the deep recesses of our minds, almost as if they never happened. But there I was with tears streaming down my face. Alone, struggling to maintain my composure, I was unsure why this old memory affected me so deeply. Then I realized I was distressed because I could have accidentally harmed an innocent child walking down the street that da —or I could have lost my own life.

After taking some time away from writing, I confided in a friend who worked in mental health services about what had happened. I also ] told her about my ongoing trouble sleeping and the nightmares. A short time later, I made an appointment with a therapist. That’s where the journey started for me, the journey toward healing.

For decades, I had ignored the traumatic incidents I experienced in the streets of Baltimore. Like when I was 16 years old, and a guy opened fire on me from just six feet away. I still don’t know how he missed but thank goodness he did. Or the time a teenage friend and I snuck into a nightclub to hear the tantalizing sounds of the early days of rap music, only to be traumatized when a man was shot and killed inside the club as we danced to the beat. Or the time I was hanging out in Druid Hill Park on a Sunday with some friends, and a man pulled out a handgun, placed it against another man’s head, and pulled the trigger.

Back then, as young men, we didn’t think much of incidents like these. In fact, we had normalized trauma, believing that we could just sleep it off and that it would be gone by morning. We never considered that witnessing these violent acts could affect our mental health decades later and that unresolved trauma could have a significant impact on our lives and decision-making ability. I never understood why I hated the sound of fireworks as a young man and would go out of my way to avoid New Year’s Eve and Fourth of July festivities that included fireworks.

Healing is possible, and every Baltimore resident deserves a quality life.

Growing up in Baltimore, I experienced firsthand the challenges of systemic inequality, poverty, and the lure of the underground drug trade, as well as issues related to being the son of an alcoholic father.

These experiences led me into a life of crime, culminating in a federal prison sentence for drug trafficking. However, my incarceration marked a turning point, sparking a quest of self-reflection and redemption.

While serving my sentence, I took college courses and began to reimagine my future, using education and personal growth as pathways to transformation. Over the last 10 years I have authored several books that tackle complex social issues, often drawing from my own life to illuminate broader societal problems.

A Life for a Life: Poor Choices and Unresolved Trauma Is Killing America (2025), which comes out this spring, is a true story that examines the intersection of trauma, mental health, and violence. It explores my relationship with my former cellmate, Damion Neal, who tragically fell into violent crime after struggling with untreated mental health conditions. The book is both a personal reflection and a call to action to address systemic neglect of mental health and trauma.

The Colored Waiting Room (2018), which was co-written with civil rights activist Nelson Malden, connects the legacy of the civil rights movement to contemporary struggles for racial and social justice. Uprising in the City (2016) focused on the death of Freddie Gray, the systemic inequalities faced by marginalized communities, and the steps necessary for meaningful rebuilding. My first book, the one that I was writing when the traumatic memory of the shoot-out leapt back into my conscious mind, was Lessons of Redemption (2014), which chronicled my transformation from a life of crime to becoming an advocate for justice and change.

My commitment to advocacy extends beyond writing. In 2014, I worked with the Obama Administration’s Clemency Initiative to address the inequities of the criminal justice system and advocate for fairer drug policies. I have also worked at the Johns Hopkins Center for Medical Humanities & Social Medicine to raise awareness around the public health crises in Baltimore and its effects on individuals and communities.

Currently, I serve as an instructor at Coppin State University, where I educate students about the links between social justice, criminal justice, and public health. Through this role, I mentor students and continue my advocacy, hopefully inspiring the next generation of leaders and changemakers.

But the most significant area of my focus today is mental health. After being diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as a result of my early life and incarceration, I have become a vocal advocate for mental health awareness. My work highlights the impact of unresolved trauma and the need for compassionate approaches to mental health care. I know firsthand the impacts of trauma and stigma on one’s decision-making and how it has hindered communities of color from seeking treatment and counseling. I want to help tear down those barriers.

My personal story of drug dealing, gun violence, and incarceration may sound dramatic to many, but scores of people in Baltimore are trying to heal from growing up and living in a continuous state of survival. Entire neighborhoods have been subjected to generational poverty due to racist policies, leading to traumas stemming from systemic barriers to education, health care, safe housing, and economic insecurity.

These obstacles include underfunded schools, limited access to mental health services, food deserts, inadequate transportation, unaffordable housing, and restricted job opportunities. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these vulnerabilities in communities already facing instability.

In the U.S., high rates of trauma and violence stem, in part, from a lack of coordination and commitment to mental healthcare. Locally, the homicide rate, though thankfully coming down, nonetheless remains at a very high level. The opioid epidemic in Baltimore City claims even more lives, nearly 6,000 over the past half a dozen years. Meanwhile, nearly one in four high school students across Baltimore seriously considered attempting suicide in the previous year, according to a recent Annie E. Casey Foundation study. And these are not issues that only impact Baltimore. Suicide is the third leading cause of death for ages 10-24 statewide in Maryland.

Inevitably, unresolved trauma becomes a major issue for youth affected by violence and opioid overdoses. Unlike physical wounds, psychological scars can persist indefinitely, often triggered by reminders of the past. These triggers vary widely, from loud noises and flashing lights to crowded spaces or even certain sights or smells.

Addressing young people’s mental health needs requires a comprehensive approach that includes prevention and intervention, with therapy and counseling among the most effective tools to help them process experiences, develop coping skills, and gain control over their lives.

“When you live in fight-or-flight mode, it’s a daily reminder of the link between trauma and violence,” says Rev. Kim Lagree, CEO of Healing City Baltimore, a community-driven organization that emphasizes trauma-informed practices and fosters compassion. One of Healing City Baltimore’s core beliefs is that addressing systemic racism is essential to treating today’s traumas. “A lot of homicides and opioid overdoses are rooted in people hurting and trying to cope. Our youth and communities face challenges with depression and anxiety, and often lack access to quality, culturally relevant services, [which are] typically designed by people who don’t look like those they serve.”

The good news is that Baltimore, with the Healing City initiative headed by Lagree, and Maryland, more broadly, have come to the forefront nationally as leaders in addressing long-ignored issues around trauma and its consequences.

In 2020, then-Mayor Jack Young signed the Elijah Cummings Healing City Act, an initiative pushed by now-City Council President Zeke Cohen, requiring that Baltimore City agencies eliminate policies that cause trauma to citizens and provide trauma-informed training to all public-facing staff. In 2021, lawmakers in Annapolis passed the Healing Maryland Trauma Act, sponsored by Baltimore State Senator Jill Carter and Delegate Robynn Lewis.

Lagree emphasizes that healing is possible, and that every Baltimore resident deserves a quality life. “An Ubuntu quote resonates with me: ‘I am because we are.’ It perfectly captures our belief that ‘if I am not free, then neither are you,’ and vice versa.”

One of Healing City Baltimore’s roles is serving as a hub for collaborators and mental health change agents. They assist organizations in developing solutions and strategies for communities that need access to quality, culturally relevant services.

“We elevate lived experiences as expertise and embrace the voices of youth and community leaders,” Lagree says. “Organizations like We Are Us, which connects directly with men in the streets, and Heart Smiles, a youth-led group training hundreds in trauma-informed care, are making a difference,” she adds.

Research shows that men, in particular, struggle to discuss mental health issues due to societal expectations and stigma. Men are often socialized to express emotions through actions rather than words—I’m no exception here—reinforcing norms of self-reliance and stoicism. Fear of judgment, limited role models who discuss mental health openly, and cultural stigma can make men reluctant to seek help. These factors often prevent them from addressing mental health needs until they become overwhelming.

During my time in prison, I had participated in a reentry program that addressed every issue imaginable, from criminal behavior to gambling and drug and alcohol addiction. The program leaders were strict: If you didn’t speak up and actively participate, you’d be kicked out, which could potentially impact your release date.

After my release, I knew I needed to continue working on myself. So, when opportunities for therapy came up, I didn’t hesitate, though finding the right therapist proved to be a challenge. As I talked with Lagree about the impact of unresolved trauma and recalled some of my story, she shared what she went through growing up in Edmondson Village and how it informs her understanding today.

Raised in a predominantly female-led family, Lagree witnessed the impacts of trauma firsthand. Her grandfather, a combat veteran, returned home with severe mental health issues and eventually became homeless.

“He struggled with alcohol addiction and left home before I was born, when my mom was still in middle school,” Lagree says. “We couldn’t locate him for decades, leaving my grandmother to raise the family on her own. She was deeply religious and took me to church with her seven days a week. Despite our challenges, her resilience and faith provided a foundation for our family’s healing.”

Trauma affected multiple generations in Lagree’s family. “My mother and biological father both experienced addiction,” she continues. “My mom would disappear for days—or even months. Years later, when we had the chance to rebuild our relationship, the Black community still wasn’t openly discussing mental health. Growing up, it was expected that we handle family issues privately. For years, I experienced the emotional death of my mother countless times from age five to 20. Filing more than 30 missing persons reports alongside my grandmother had a significant mental impact.”

Along with speaking with Lagree about Healing City Baltimore and efforts to address trauma in the city, I also wanted to talk with Rev. Donte Hickman, whom I’ve actually known since our teenage years. One of the most respected faith and community leaders in the city, he offers a unique perspective on community healing from trauma, which includes having to rebuild a neighborhood senior housing complex that was under construction and destroyed in the Uprising after the death of Freddie Gray.

Also, a Baltimore native, he has led the Southern Baptist Church on the east side of town for two decades. A pastor, he nonetheless believes that spirituality and religion should not be the sole tools for healing. He has long talked about the impact of trauma among cit residents, youth in particular, and the deep need for accessible mental health in Baltimore.

“Spirituality should enhance social awareness, not blind us to reality,” he explains. “Some use it to block out real threats [to mental health].”

Hickman acknowledges that while Baltimore is making economic and infrastructure strides with redevelopment underway in many parts of the city, people and communities still grapple with trauma. Ex-offenders, for example, he says, face enormous challenges to healing when they return, and it can be difficult for them to navigate life outside of prison. Failure to adequately address these mental health needs will not just hold individuals back but hold the city back as well, he adds.

“Healing can be misunderstood; spirituality is often misused, becoming a shield against pain,” Hickman says. “Karl Marx said, ‘religion is the opiate of the masses.’ Similarly, spirituality can insulate us from violence and trauma, giving a false sense of [physical and psychological] security.”

He believes true healing requires intentional effort. “We must first acknowledge what’s wrong, rather than using spirituality to avoid it. Instead, it should encourage us to confront our realities.”

Hickman acknowledges that while Baltimore is making economic and infrastructure strides…people and communities still grapple with trauma…failure to adequately address these mental health needs will not just hold individuals back, but hold the city back, as well.

The mental health impact of violence is profound in the neighborhoods around his church, especially among young people, leading to anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Children shouldn’t live in fear at school, worried about what’s around the corner, Hickman continues.

“This contradicts the teachings of Jesus, who said, ‘I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly.’”

In 2021, Hickman and his congregation faced the personal impact of random community violence when Evelyn Player, a church volunteer, was found dead in the church restroom. Hickman arrived to find police tape surrounding the church, shocked to learn she had been murdered. “I thought, ‘Who would stab a woman in a church?’ It made me realize that not everyone views the church as a sacred space,” he reflects.

After the tragedy, Hickman addressed the congregation about the complicated feeling of being protected by God in such a moment and organized a prayer vigil to honor Player and unite the community in the grieving and healing process. This collective spirit has been evident during past violence, such as the 2015 riots following Freddie Gray’s death.

“We went door to door and engaged with seniors to understand their experiences,” he recalls. The day of Player’s murder was no different. Hickman wanted to bring the community together to affirm their faith and support one another. Gov. Wes Moore, then a church member, attended the vigil, emphasizing the importance of community in the healing process.

Tragedies, such as the murder of a beloved community member like Evelyn Player or the death of an innocent man in police custody, as in the case of Freddie Gray, do have the potential to unite people across boundaries, fostering a shared determination to heal.

For long-overdue healing in Baltimore to occur, the community must show up for each other, transcending both real and imagined divides, Hickman says. But there must still be broad and affordable access to mental health care, as well. “If we ignore the needs of the least and most vulnerable in our communities,” Hickman says, “we will feel the repercussions in all neighborhoods.”

I also know firsthand the impact of trauma and stigma on one’s decision-making and how it has all too often hindered communities of color from seeking treatment and counseling. I want to help tear down those barriers and help communities return to being well again, but it’s also important that if I don’t take care of myself, I won’t be of much service to others.

A therapist once told me I had something called the “Superman Syndrome” or “Superman Complex.” It’s an unhealthy sense of responsibility rooted in the belief that others are incapable of handling even simple tasks on their own. Those with this complex—or its counterpart, Superwoman Syndrome—often see themselves as invincible and incapable of failure. They’re driven by an intense need to fix everyone around them, all while believing they have no issues of their own. She described me to a ‘T’ and that was the day that I started to pay more attention to my own emotions and my own feelings—and take on the problems of others as if they were my own.

At the same time, while writing my first book, Lessons of Redemption, I worried about how people might perceive my story. Gregory Kane, a former columnist for The Baltimore Sun, gave me invaluable advice: “Don’t worry about those fools. Just be honest in your writing.” Which is also good advice for life. I’ll never forget when he said, “Write until your hand falls off, and if it does, learn to write with the other hand.”

At the time, Kane was battling cancer, and his resilience inspired me. If he could fight that battle, I could certainly put words down on paper. Those moments, combined with my conviction to always rise to the occasion when it mattered, played a major role in shaping my journey.