Business & Development

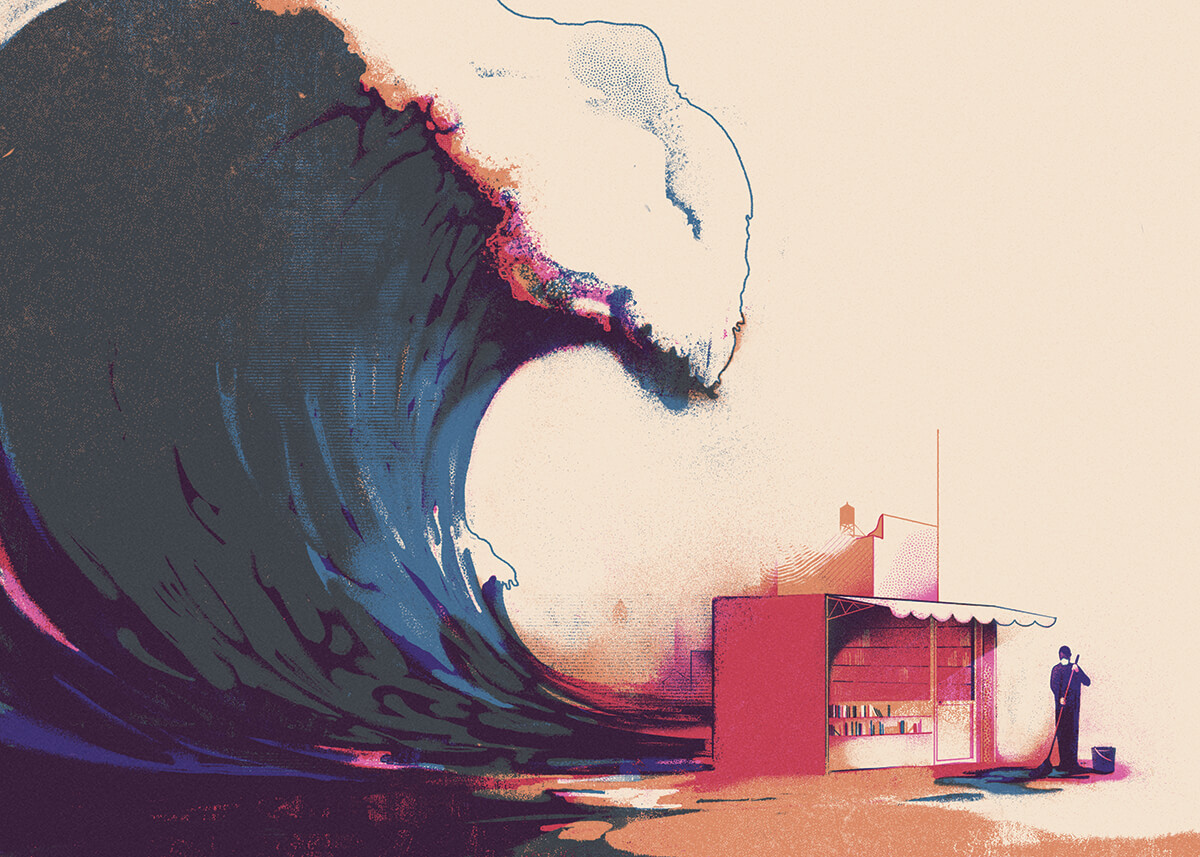

A Wave of Woe Awaits

It’s never good news when the bankruptcy business is booming.

As a bankruptcy attorney, Dennis J. Shaffer sees people at one of the most challenging times in their lives. And with the pandemic-hobbled economy, he’s getting busier. Take, for example, his client in the personal service industry (who, understandably, asked that their name be withheld).

It was almost a year ago, shortly after the coronavirus first landed on our shores, that the client started having trouble paying the business’ bills, including loan payments. “In January, I realized that the debt structure was increasingly tough to stay current with,” the client says.

The business was shuttered for three and a half months due to the non-essential business closure orders, then, once it reopened in July, it struggled with the shortened hours and lack of space to adhere to social-distancing mandates. Working closely with Shaffer, the business owner opted to file Chapter 11. But the owner is still unsure how it will turn out.

“[The bankruptcy] has added to the uncertainty of tomorrow, because the virus is still with us and the fears continue,” the client admits. “Also, the notification of the bankruptcy has caused a negative reaction with our clients. Employees, clients, friends, and family look at you differently.”

But Shaffer, a 20-year veteran in the field who has been consistently recognized among the “Best Lawyers in America,” says society needs to reframe how it thinks of bankruptcy, particularly as the pandemic takes its toll on more businesses. He points out that while it is about paying off creditors, it can also give debtors a fresh start. And he prefers to refer to himself as a “restructuring professional” rather than a bankruptcy attorney, since restructurings can be done without declaring bankruptcy.

“Most restructuring professionals see themselves as problem solvers,” he says. “Bankruptcy isn’t a bad word. Even though it has an extreme negative connotation, it really is a tool. The various chapters of the bankruptcy code offer specific relief that are great tools to help alleviate problems for clients.”

And that rethinking of the bankruptcy stigma he refers to may eventually happen simply because of the sheer volume of filings to come: Shaffer and others in the field know there’s a tidal wave of business failures on the horizon.

“BANKRUPTCY ISN’T A BAD WORD. EVEN THOUGH IT HAS AN EXTREME NEGATIVE CONNOTATION, IT REALLY IS A TOOL.”

While commercial bankruptcy filings nudged up in September of 2020, a report by the American Bankruptcy Institute notes that, nationwide, overall filings were down 35 percent over the same month in 2019, a trend mirrored in Maryland. But that’s misleading: It’s because courts, once shuttered, are now congested with case backlogs. Worse still, others facing financial failure can’t even afford the fees to file.

Alessandro Rebucci, an associate professor at The Johns Hopkins University Carey School of Business and an expert in finance and economics, says the pandemic is unique. Normally, bankruptcies correlate to unemployment.

“The COVID recession is like no other due to initial government support,” says Rebucci, citing the CARES Act, payroll protection loans, and lender forbearance. “All the federal programs ultimately are contributing to keep the economy as a whole, and its parts, afloat.” But it won’t last.

“Many large companies have succumbed already,” he says. “We are not out of the woods, and we could easily see a delayed wave of defaults and bankruptcies in 2021 to ’22.”

Shaffer is already seeing an uptick in client activity and bankruptcy across all small to mid-sized businesses, many family-owned, including salons, restaurants, and franchises. He anticipates some businesses will shut down while others will avail themselves of bankruptcy protections.

“One of the first questions I ask clients is, ‘What do you want to accomplish? What is an ideal outcome for you?’” Shaffer says. Bankruptcy is often a solid option, but he understands the hesitation. “[Bankruptcy] presents more opportunities to help people, but it’s more personal,” he says. (It’s also more public—bankruptcies are listed in The Daily Record.)

Sometimes, Shaffer says, creditors will negotiate with debtors without the need for bankruptcy’s protection. For better or worse, the creditor is in a partnership with the debtor and it behooves the creditors to find a solution, even if they can’t collect on a debt in its entirety.

Failing that, there are the various chapters. Typically, individuals file under Chapter 7, to wipe out all debt, or 13, to restructure and pay their debt over time. Chapter 11 can be used by an individual or a business to restructure the existing debt in a way that hopefully allows the business to stay open, though it can also mean the business would have to liquidate its assets to pay creditors.

One difficulty in dealing with small business bankruptcy is that the assets are often backed by a personal guarantee. Not only is the business on the line, but creditors can also come after personal assets, like an individual’s home. Even here, Shaffer says, there are solutions and opportunities to negotiate with creditors.

As painful as the process is for those facing financial failure, this is as good a time as any to go bankrupt.

The Small Business Reorganization Act passed in February 2020, making it faster and less expensive for small businesses to file while also offering a higher likelihood of salvaging the business, and eligibility was expanded under the CARES Act.

But that doesn’t relieve the emotional toll it takes on the filer.

Shaffer’s client in the personal service business says they feel like their entire life is hinging on getting through the bankruptcy successfully.

“Some days look more promising than others,” the client says. “It’s a learning process, and each day and phase brings on new challenges. I think we are between struggling and rebounding.”

“WE COULD EASILY SEE A DELAYED WAVE OF DEFAULTS AND BANKRUPTCIES IN 2021 TO ’22.”

Dr. Jodi Jacobson Frey is a professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore’s School of Social Work who specializes in workplace behavioral health. Among her appointments, Frey is co-chair of the Workplace Suicide Prevention and Postvention Committee of the American Association of Suicidology. Frey says that even without a pandemic, financial distress can be severe because it impacts every part of a person’s life, from their relationships and general happiness to their basic needs for food and shelter. Also accompanying financial problems are feelings of shame and embarrassment.

“Bankruptcy tends to be full of fear of the unknown, as most people don’t know someone who’s ever declared bankruptcy and they don’t understand the laws,” says Frey. “Fear can be paralyzing, causing people to live in denial, to ignore the bills, to avoid the calls from creditors, or to fall back on using credit cards.”

Frey compares financial distress to a rubber band. You can stretch it, but it will bounce back only so many times before it breaks. In this pandemic, with individuals and businesses dealing with myriad stressors, the rubber band is stretched too far.

“Financial distress leads to financial despair, and that leads to poor health and mental-health outcomes,” she says, including substance use, depression, or aggression, even suicide. And pandemic isolation only makes it harder to tap the support networks needed to get through a tough time.

“People are feeling hopeless, like they have no options,” she says. “Fear prevents us from reaching out until it’s too late.”

Shaffer advises those facing failure to not delay.

“If you know there’s an issue, if you’re maybe okay now but you know business is down, speak with a restructuring professional sooner rather than later,” he says. Most attorneys offer a free initial consultation, and talking to an attorney doesn’t always lead to filing—sometimes there are other options, but they dwindle if you wait too long, he says.

Shaffer has already assisted a client who was a restaurant supplier hit hard when the chain it outfitted shut down and canceled plans for new stores.

“He couldn’t wait a year for business to come back,” he says. “This person’s business was going to shut down, and he knew it.”

The business was wound down in an orderly fashion. They maximized the sale of assets and worked with creditors to re-negotiate repayment amounts.

“Ultimately, the individual had no liability and even had a little equity left in the business.”

Shaffer underscores that anyone struggling financially is not alone.

“These things happen, and now they’re happening all over the place, but there are options. At the end of the day, it doesn’t need to be a total loss.”