Business & Development

The Revivalist

Bill Struever remade Baltimore’s harbor neighborhoods. His second act may be more dramatic.

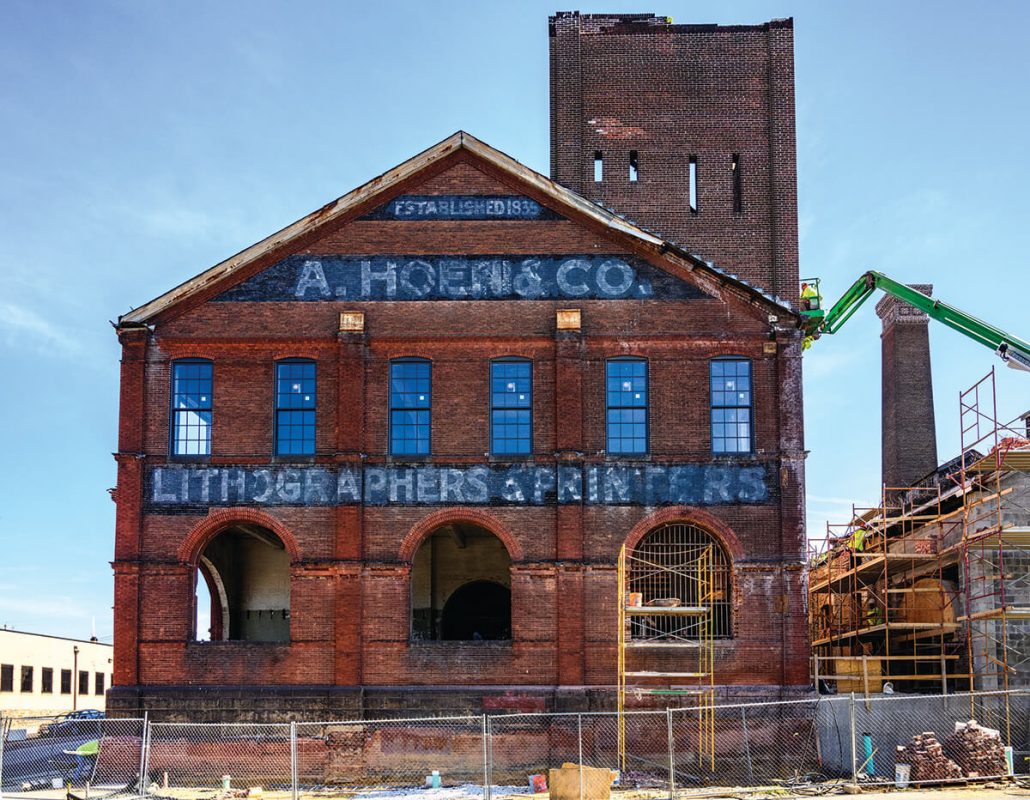

Bill Struever is standing inside the belly of a beast. For nearly a century, this massive 85,000-square-foot brick complex in East Baltimore was home to one of the most prolific lithographic printing companies in the world.

In its heyday, A. Hoen & Co. produced National Geographic maps, Buffalo Bill Cody posters, Dr. Seuss books, and Topps baseball cards. But it’s been shuttered since 1981, slowly crumbling over the past four decades like much of the surrounding neighborhood in the distressed area north of The Johns Hopkins Hospital and “north of the tracks” (read: wrong side to investors) where Amtrak rolls into town. Struever, however, is in his element.

“We’ve unearthed some of the old lithograph stones,” says the rumpled, 67-year-old developer, whose company, Cross Street Partners, is leading the long-hoped-for rehabilitation of the abandoned Hoen factory, which consumes an entire city block between East Biddle and East Chase.

Struever, on his way to a meeting in rolled-up jeans and a plaid workshirt, earned a degree in urban anthropology at Brown University and a master electrician’s license on the side. To his credit—and Baltimore’s benefit—he has always paid as much attention to the history and details of the buildings he’s repurposed as the construction, design, and financing process. He notes, for example, the relief sculpture in honor of Alois Senefelder, the inventor of the lithograph process, and the Latin words, Saxa Loquuntur—“the stones tell”—above the Hoen plant entrance.

But more than anything, it’s the reimagining of urban neighborhoods that animates him. He read acclaimed New York journalist, activist, and author Jane Jacobs’ book in college—she’d helped save lower Manhattan from urban highway destruction—and it became his Bible.

“You look out the window and realize Hopkins and the Henderson-Hopkins School [the first new school in the area in more than two decades] and the new Eager Park townhomes and apartments are just down the street,” says Struever, whose enthusiasm is both genuine, and, like any great salesman, contagious. “The American Brewery [home to nonprofit Humanim today] is a few blocks away, and there’s The Food Hub in the old Eastern Pumping Station on Oliver Street.”

Both the redevelopment of the wild-looking, late-19th-century American Brewery building—its central tower housed a 10,000-bushel grain elevator—and the Eastern Pumping Station are Struever partnership efforts. “To me, this is as exciting as anything we’ve ever done.” Which is saying something.

Practically everything Baltimoreans love about the city’s repurposed built environment—Canton Cove and the Can Company factory, Cross Street Market, Belvedere Square, the Tindeco and Bond Street wharfs, Stieff Silver in Hampden, Under Armour’s headquarters in the former detergent plant at Tide Point, the Clipper Mill complex, even the winking neon Mr. Boh atop Brewers Hill—Struever played a major hand in developing.

“When people ride Amtrak through East Baltimore, coming to the city for the first time,” says Struever, optimistic as ever, “they are going to see a transformation from the old sets of The Wire.”

After years spent digging out from his company’s collapse in the wake of the global financial meltdown in 2007, the visionary developer is now back in the fray with adaptive reuse projects in East and West Baltimore—a dramatic geographic shift in focus from the “white L” to the city’s historically redlined “black butterfly.”

“[People] are going to see a transformation from the old sets of The Wire.”

Mary Ellen Hayward met then 25-year-old Bill Struever in the summer of 1977, shortly after finishing her doctorate in American Studies. He was rehabbing rowhouses in Federal Hill and had already reached out to the Maryland Historic Trust about a research project around the homes and buildings in the Federal Hill National Register Historic District. She tapped on the door of his small office tucked in a recently rehabbed house on East Cross Street and inquired about a job.

“‘Can you write?’ was his first question,” Hayward says. “Bill was the same as he is now. He could be a little spacey,” Hayward adds with a chuckle. “He’s not always engaged with the conversation right in front of him because he’s looking ahead. Then, when he’s excited about something that interests him, he can talk fast, be hard to follow, jumping from idea to idea. He walks fast, too. He was that way when he was 25.”

At the time, blocks of rowhouses on Federal Hill’s north end stood vacant behind chain-link fencing, recalls Hayward, who went on to write several books about Charm City’s architecture and rowhomes. Acquired by the city when plans were still in the works to build a bridge across the Inner Harbor—to link to a planned urban expressway through Fells Point—the rowhouses had been abandoned after the defeat of the highway by local activists, including a certain feisty social worker named Barbara Mikulski.

Other houses on South Charles Street remained burned-out shells, and more homes on South Hanover Street were empty and boarded up. Stories in The Sun referred to the “slums” of South Baltimore. A body was reportedly discovered in one of the abandoned rowhomes they purchased.

Three years earlier, Struever’s mother had accepted a job at Hopkins teaching Renaissance history, and he’d decided to tag along to the city following graduation from Brown. He’d learned of then-Mayor William Donald Schaefer’s $1 housing program and saw potential opportunity in Baltimore even as others were fleeing for the suburbs. He dragged his brother Fred and college roommate, Cobber Eccles, with him to the city.

The trio bought a pickup and plastered a hammer logo on it, earning beer money their first year from basic home improvements. “I thought it might be something that lasted a year before I headed to graduate school,” says Eccles, who remains a Struever partner.

Their first home at 436 Grindall Street in Federal Hill—Struever has never forgotten the number—was purchased with a $10,000 loan from his mother. They eventually rehabbed three more in the group and created a grassy knoll between them, naming it Chandler’s Yard in tribute to the ship chandlers who had lived nearby. But Struever soon realized that if they were going to be successful flipping old houses, they needed to revitalize the neighborhood’s commercial life—jump-start the kind of businesses, restaurants, and shops that make urban neighborhoods convenient, attractive, and fun for pioneering young home buyers.

“Our banker told me someone needed to do something with the Cross Street Market and reopen the nearby storefronts,” Struever says. “Otherwise, nothing would sell. [But] I didn’t have any money. Then he told me he’d loan me the money to do it. We eventually bought 40 storefronts, and I’ve been borrowing money ever since.” Struever and his partners launched the Sundae Times ice cream parlor on the south side of Cross Street, a children’s bookstore, and a gourmet cheese stall in the market.

Their most successful venture proved to be a bar and live-music venue called Hammerjacks at the corner of Cross and South Charles streets. “We sold more cases of Budweiser than any bar east of the Mississippi,” Struever says with a bit of pride.

Ever restless and adventurous (Struever has been known to kayak across the harbor to meetings), he quickly turned his attention to more audacious projects, such as redeveloping Clipper Mill, the former sail factory on the Jones Falls. Inevitably, as with the Tindeco, Canton Cove, and American Can Company projects, he saw value where few dared to tread. He also displayed a knack for marrying private investments with public subsidies and tax credits, which continues to this day. In the process, he reshaped the city’s deindustrialized harbor and decaying riverfront mills into national models of adapted renewal.

Struever didn’t invent the exposed piping, beam, and brick aesthetic, nor the modern commercial, office, and residential district, as Baltimore architect and former Struever collaborator Klaus Philipsen points out. That had been done previously in places such as SoHo, San Francisco’s Ghiradelli Square, and the docks of East London. But Struever convinced an often-timid Baltimore, Philipsen recalls, that it could be done here. “I arrived in Baltimore [from Germany] about when Bill did, and the city was in transition, and not in a good way,” Philipsen says. “He and his team were enterprising, the first to use adaptive reuse principles. He understood the power of design and value in preserving these assets. It’s much easier to go to the suburbs and build where nothing else exists.”

Struever’s mentors included the also famously rumpled, civic-minded developer James Rouse, who built Harborplace, Cross Keys, and, from whole cloth, Columbia. Ted Rouse, James’ son, became the fourth partner of Struever’s team early on. Not that Struever was in concert with James Rouse on everything. “We disagreed over Columbia,” he says. “Why create something out there when you already have the density and ingredients and creative energy of city life? I was never interested in the suburbs. It’s fake. Nothing’s authentic.”

Another mentor was Walter Sondheim, the former chairman of the school board who spearheaded the desegregation of Baltimore’s public schools following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. Struever, too, sat on the Baltimore City Board of Education for a period, among numerous boards over the years. He also practiced what he preached, living in the city and sending his daughters to public schools.

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but I don’t think anyone can deny the redevelopment of the Can Company and Canton waterfront and the rest were thoughtfully done,” says Abell Foundation president Robert Embry Jr., reflecting on Struever’s landmark accomplishments. “He’s a city treasure. I grew up in Northeast Baltimore, and I’d never seen the water there as a kid. It was industrial. There was no reason to go down there.”

“It is much easier to go to the suburbs and build where nothing else exists.”

There were hiccups along the way—a failed effort to develop the Port Liberty area and the early ’90s recession took their tolls—but eventually the success of Struever Bros., Eccles, and Rouse enticed the celebrated developer to look beyond the beltway to places such as Wilmington, Delaware; Durham, North Carolina; and Providence, Rhode Island—even Boston and Fenway Park. And then, leveraged to the hilt as the financial crisis hit in 2007, the whole company came tumbling down.

Projects such as the State Center, Harbor East, and the completion of Brewers Hill had to be handed off to other developers. The Olmstead, a planned 12-story building on St. Paul Street in Charles Village, stayed a fenced-in hole in the ground. Lawsuits for failure to pay contractors and vendors and loans piled up across multiple states. Struever never declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy, which would’ve been the easier and personally less costly route, instead spending the subsequent half-decade mitigating the damage and working out of the mess. The formation of Cross Street Partners enabled him to begin again with consulting projects, but the heavy losses essentially sidelined him until recently in terms of full-blown development work.

“A lot of sleepless nights,” Struever says. “We employed about 400 people, and there were hundreds of others affected, obviously. That’s what keeps you up, trying to figure a way out.”

The $30 million Hoen project, which recently received $1.6 million grant from the federal government and a visit from a Trump Administration commerce official, has already attracted major tenants, including Strong City Baltimore and the Association of Building Contractors, which will move their trades training programs here.

With exterior brickwork and window replacement underway, the building is scheduled to open in 2020. Whether the A. Hoen & Co. Lithograph complex—135 years after its construction—can again serve as a catalyst for wider East Baltimore revitalization and convince mixed-income, black homeowners to remain, return, or buy in the broader neighborhood remains a open question. It could take a generation. Or two. It took decades for a tipping point of new young families in Canton and Federal Hill to send their kids to local public schools.

Barbara Mikulski says part of Struever’s genius in Locust Point and Canton, in particular, was recognizing not just the potential to renovate ex-warehouses and make them look hip, but the 21st-century innovation economy jobs they could attract. The 83-year-old, the longest-serving woman in the history of the U.S. Congress, had worked a summer in one of those old Canton factories making ketchup.

A half-century later, as senator, she helped bring a NASA incubator office into the Can Company building. In his second act in East Baltimore, Struever’s taking a calculated gamble on the continued expansion of Hopkins’ medical-research network and local nonprofits, like Strong City and Humanim, as well as the new Food Hub incubator and the Association of Building Contractors skilled workforce programs, to generate jobs. It’s a new kind of undertaking. It’s not just the buildings that have been left behind here, but the people who live in this community. Unemployment rates in East Baltimore are double that of the city as a whole. In some neighborhoods, half of the residents didn’t graduate from high school. “There needs to be a holistic approach,” cautions Rev. Donte Hickman of nearby Southern Baptist Church.

“The area needs more mass transit, the whole city does, and we need to invest more in our schools. That’s crucial, too,” adds Mikulski, who has paid close attention to Struever’s projects over the years. No one person is going to fix the city, she stresses, including the next mayor.

“There are no saviors,” she says. “But one thing Bill likes is to take people to Portland, or New York, and see what we can learn from each other. Pittsburgh and Detroit suffered the same body blows, and look at the great things happening in those places. We don’t want to copy them, but we can gather ideas. Bill gets people talking to other people about the city, its spaces, and [he] imagines what Baltimore can do—and it’s never cookie-cutter stuff. That’s what he does best.”