News & Community

Brand Ambassador

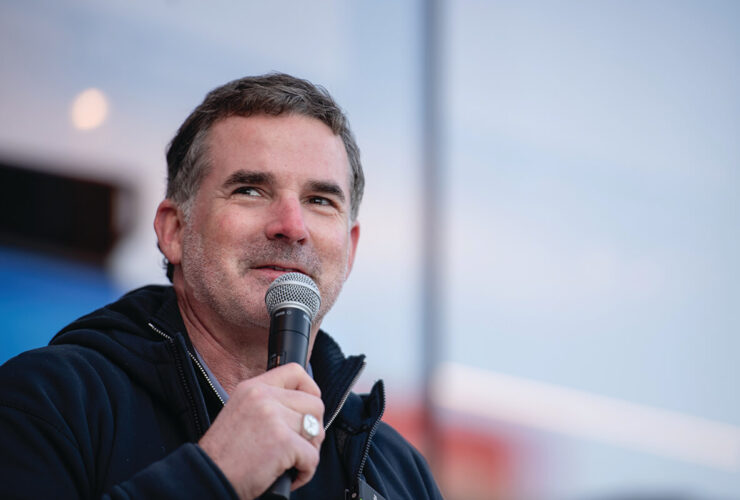

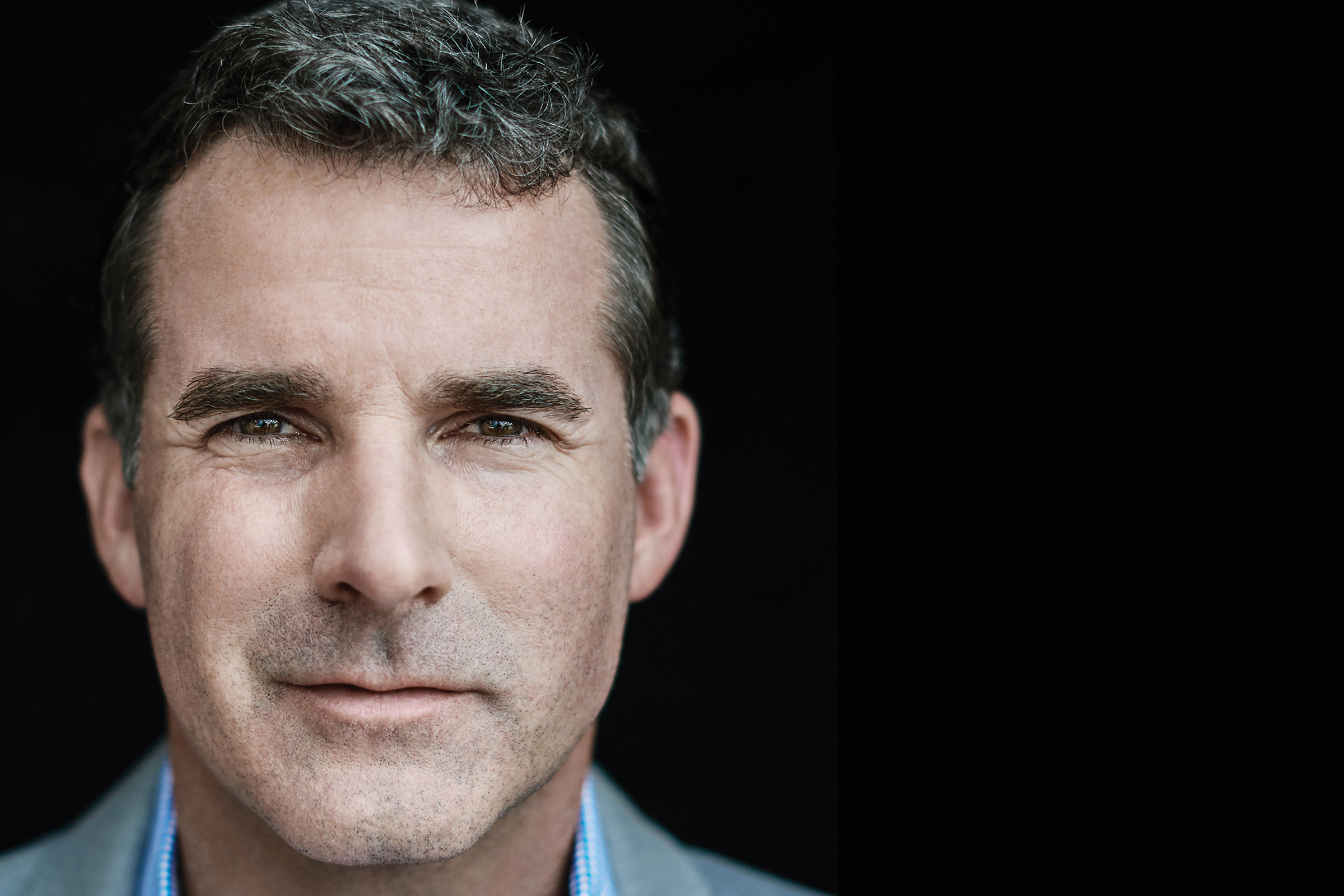

After a tumultuous year, Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank is newly resolved to see his company—and city—thrive.

evin Plank has a telescope in his office aimed not at the heavens, but at a hotel. From his suite on the fourth floor of the Cascade Building at Under Armour’s Tide Point headquarters, Baltimore’s sportiest billionaire can gaze across the water to the Sagamore Pendry, the Fells Point luxury hotel he opened in March.

evin Plank has a telescope in his office aimed not at the heavens, but at a hotel. From his suite on the fourth floor of the Cascade Building at Under Armour’s Tide Point headquarters, Baltimore’s sportiest billionaire can gaze across the water to the Sagamore Pendry, the Fells Point luxury hotel he opened in March.

Dripping with symbolism, the instrument was a gift from the property’s general manager, who already knows what everyone who works for Plank will discover soon enough: The boss will be watching.

Not that Plank is a micromanager—he didn’t pick out carpet or trim for the guest rooms. But he knows that his employees are among the most public faces of his brands, and to Plank, brand is king. He focuses on his businesses’ reputations with the precision of a Jordan Spieth putt.

Plank’s never been a reticent or reclusive CEO, but he’s far more comfortable discussing the company he famously dreamed up while an undersized, overachieving football player at the University of Maryland than he is talking about himself. That’s one reason these are trying times for him both professionally and personally.

If he had his druthers, he’d want people discussing his many projects, both philanthropic and for-profit, in his beloved hometown. Instead, throughout a tumultuous year in which Under Armour’s sales were sluggish, its stock price slumped, and his awkward foray into national politics—whether intentional or not—backfired, he’s found himself in the media spotlight. The glare has been harsh.

“We’re taking a lot of heat right now for a number of reasons,” Plank says. “But there’s so much care for this brand. That’s one of the things that has been tested. Hopefully, people see that our heart is true, but number one right now is making our brand something that will make Baltimore, and all of America, frankly, really proud.”

It’s a beautiful early October day, and through the windows of his corner office, Plank has a striking panoramic view of the city. The only ripples in the water are the wakes of water taxis, another of his recent acquisitions, crisscrossing the harbor.

He’s wearing a gray long-sleeve shirt, the familiar interlocking UA logo displayed on the chest, and black pants, a casual outfit that reflects his relaxed, confident attitude. Flecks of gray pepper his dark hair, but at age 45 he still exudes the youthful jockishness of his days as a Terp. Despite the challenges his company and his city face, as always, Plank is unabashedly optimistic about the future.

“One of the things I’m most proud of is the fight we’ve seen from the team,” says Plank, who often employs coachspeak when discussing corporate culture. “It would be a lot easier if we just had to hug instead of fight, but sometimes you don’t get that choice.”

He should know. Kevin Plank has been a fighter all his life.

The youngest of five boys, Plank grew up in the Washington, D.C. suburb of Kensington. His father, William, was a real estate developer, while his mother, Jayne, worked for the state department and served as mayor. Despite the wide age range of the children, there was rarely a dull moment in the Plank residence.

“My mom would be constantly shopping for food,” Plank’s brother Scott says. “Eventually the food would run out at our house and we would go over to a friend’s house or up to the sub shop.”

Plank was a rambunctious kid who was self-sufficient, easygoing, reliable, and a bit of a daredevil, his mother told Bethesda Magazine in 2009. “I got a call one day at work that Kevin tried to fly from the apple tree in our backyard,” she said. Her son had broken his wrist. “He was dressed in his Superman outfit.”

“Kevin was always hustling,” Scott says. “He was the kid who was cutting grass and shoveling snow. Some kids have a hobby—his was not robotics or model building, it was doing odd jobs and working.”

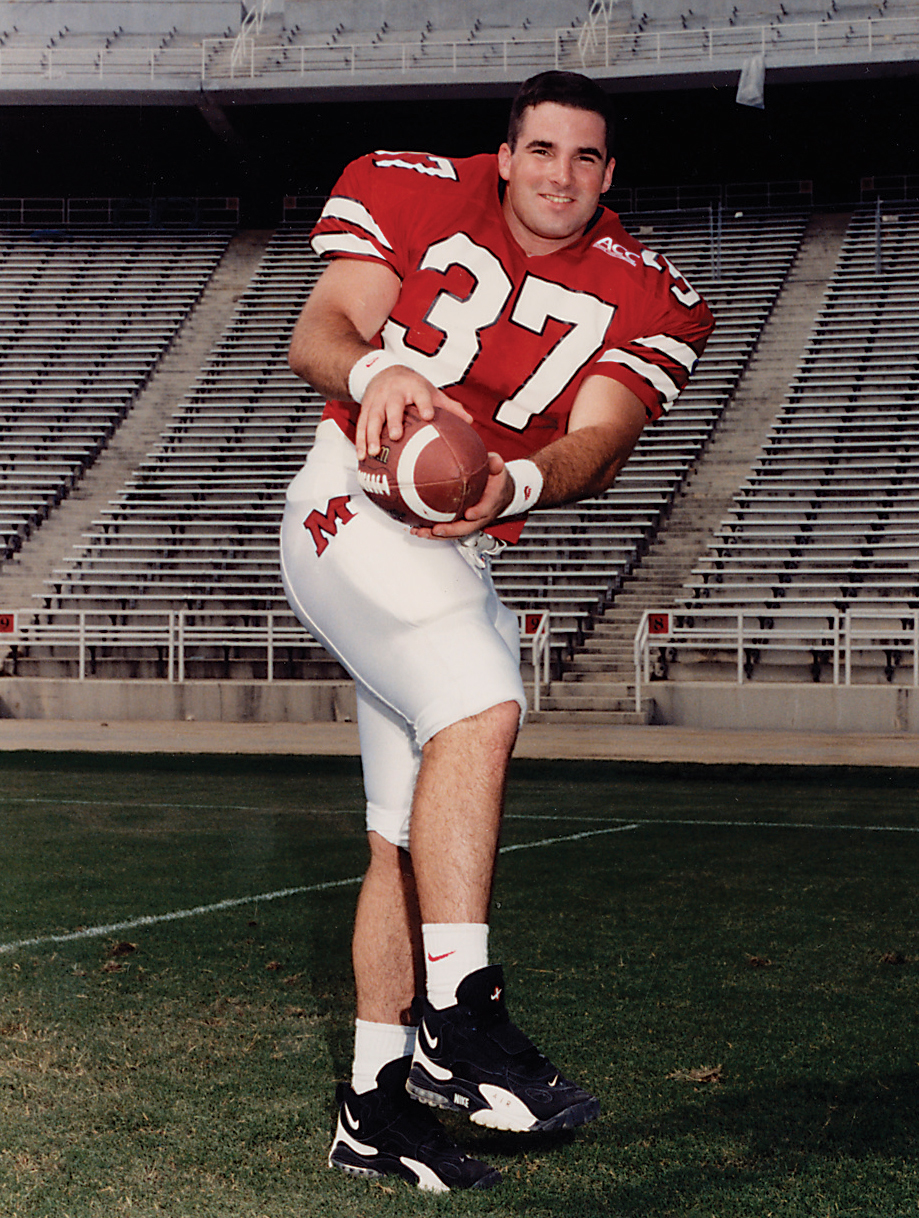

Sports played a prominent role in the household, and lacrosse and football provided a positive environment for Plank to focus his energy, which wasn’t always easily harnessed. He was kicked out of Montgomery County’s prestigious Georgetown Prep after his sophomore year of high school for a losing combination of failing grades and fighting, according to Forbes. At St. John’s College High School in Washington, he improved his academics while continuing to play his ass off on the football field. Plank was a fiery player, and after a year at Fork Union Military Academy, he walked onto the team at the University of Maryland, determined to eventually earn a scholarship. By his senior year not only did he have a free ride, he was named special teams captain as well.

“He was a little bit above average as an athlete, but what he brought was his attitude,” says Mark Duffner, his college coach. “We used him both at linebacker and fullback. He was a very highly motivated, high-energy player. If you’re a very competitive guy and you’ve got toughness, then you can be a contributor. Those are the attributes he had. You could always count on him coming out of the game looking like he’d gone through the war, because he was going to give all he had.”

Plank’s entrepreneurial spirit bloomed from his earliest days in College Park. He shoveled snow, bounced at a bar, parked cars, worked in construction, and even sold T-shirts at Grateful Dead concerts (the latter aided by his now wife, D.J.). During his second year on campus, he started a rose delivery business from his dorm room. The $17,000 he made was seed money for Under Armour.

“My first year we sold 100 dozen roses, then 250, then 650,” he recalled in his 2016 commencement address at Maryland. “By my senior year I had a credit card machine in my room, 40 drivers delivering, and five operators working the phones and taking orders, and, of course, upselling. You know, for just $10 more we can put that in a vase!”

delivering the 2016 commencement address at the university of maryland.

The speech was sprinkled with so many mentions of entrepreneurs, entrepreneurism, and entrepreneurship that taking a pull every time he mentioned the word or its various forms would have made a good drinking game for grads who snuck flasks into the ceremony.

Plank is unapologetic about his passion for the subject.

“Twenty years ago I would have said there is no idea more fundamentally American than being an entrepreneur,” he said. “Now, 20 years in . . . my perspective has changed. Frankly, there is nothing more global than being an entrepreneur. It’s the most desired export that we have as a nation.”

In 2006, Plank sponsored the first Cupid’s Cup at Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business. A sort of hybrid American Idol and Shark Tank, the annual competition hands out cash prizes to entrepreneurs with winning business ideas. It’s grown dramatically since its inception. The first few were held at the University of Maryland, but in March, it went national. The 2017 event at Northwestern University awarded $100,000 (in exchange for zero equity in the companies).

“I’ve seen this now on several occasions, where he talks about the basic lessons he learned and the grit and determination all entrepreneurs have to have to succeed,” says Alexander Triantis, dean of the Smith School. “Kevin’s about huge vision. He’s always looking a few mountains past where everybody else is and understanding that it never will be easy getting there, but if you’re not doing it for the money or fame, but because it’s something you believe in and love doing, then you can succeed.”

Eric Golman and two of his friends won last year’s cup. The $80,000 they pocketed enabled them to develop their product—a tea- and superfood-infused coffee that can be dropped in hot water and brewed in its bag in four minutes—and produce the initial inventory to get it into stores.

Last winter, they met with Plank at Under Armour’s headquarters to discuss their company, JavaZen, over veggie wraps at lunch.

“There was some intimidation going in, because he’s built something so huge and had such massive success,” Golman says. “We were shocked by how laid back he was. He made it easy to be open and transparent with our business. We had a 25-minute meeting scheduled, but it ended up going on for over an hour. People came in saying the next meeting had to start.”

Plank ignored them.

“The main advice that still sticks with us was his focus on selling one product and doing that well,” Golman says. “He said there were about seven years where he just sold one shirt, and he didn’t make the next product until that was perfect.”

If you don’t know Under Armour’s moisture-free rags-to-riches tale by now, you must be wearing shoes with a swoosh. It’s a story that has become entrenched in business school lore: How, as a player at Maryland, Plank became increasingly frustrated with the heavy, sweat-soaked cotton T-shirts he wore under his football uniform and began thinking there had to be a better way. How he scraped together a few hundred dollars to have a College Park tailor sew seven prototypes, then asked his teammates and other Terrapin athletes to demo them. How he started the company in 1996 in his grandmother’s house in Georgetown and drove around the country in his cracked-windshield Ford Explorer passing shirts out to friends, former teammates, equipment managers—anyone who would take one and spread the gospel about his new line of performance apparel.

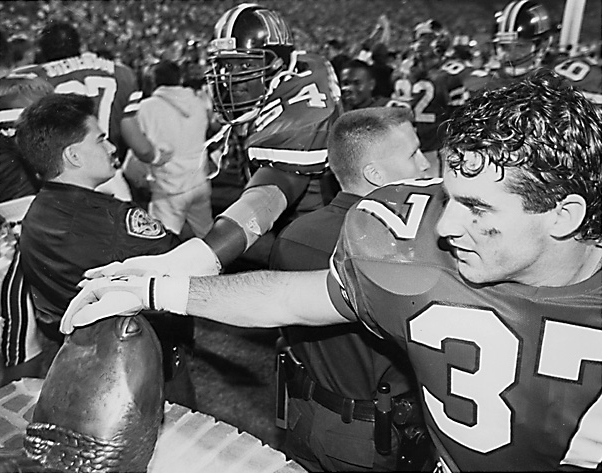

kevin plank posing while playing special teams for the Terps. courtesy of university of maryland archives.

By the end of 1996, Plank made his first team sale, to Georgia Tech, and Under Armour earned $17,000. Two years later, he moved the company to Baltimore, forging a bond with the tough, blue-collar town in which he saw similarities with himself.

“When we moved to Baltimore, people asked why,” he said on CNBC last year. “I said, ‘I can’t tell you.’ Something drew me there. Something fit the brand, the culture, the ethos. The work boots, the lunch pail, the attitude to that city—it is Under Armour.”

From a handful of employees on Sharp Street to 14,000 around the world, from a few thousand dollars in sales to more than $4.8 billion last year, Under Armour has grown beyond almost anyone’s wildest dreams—except Plank’s.

“Kevin never would have said the company’s going to be this international multizillion dollar whatever, but he never would have thought he couldn’t do that either,” Scott says.

Plank’s confidence, his unbridled belief in himself, extends to his vision for Baltimore. Aside from the hotel and the water taxis, he’s invested millions of dollars in a thoroughbred farm and a whiskey distillery, and his company has given millions more to build rec centers and fields, outfit the city’s high school athletes, redesign firehouse gyms, and sponsor events like the Baltimore Running Festival, now in its 17th year.

“When we were getting ready to go into our second year, I had a conversation with him, and Kevin said, ‘You know what I’m going to do? I’m going to put $100,000 up,” Baltimore Mayor Catherine Pugh says about the running festival. (Plank actually provided $200,000 a year for 10 years, plus free shirts for the runners.) “We started out with 6,600 people, and now it is at about 23,000. I attribute a lot of that to Kevin’s initial investment. He would come to the marathon, look at the crowd and say, ‘See what you started?’ He’s very humble, easy to get to know. I think he’s a visionary, and we need more of them.”

Much of Under Armour’s charitable and civic work is detailed in a new campaign, dubbed We Will, encouraging volunteerism and aiding Baltimore City. Plank is definitely a “we will” kind of guy, but he’s often frustrated by living in a “no you won’t” kind of world.

As the Under Armour logo and Sagamore brand continue to pop up on more and more projects, he’s faced some backlash by people weary of his ambitions. After all, he’s not an elected official. Should one man—a private citizen—have so much power in one city?

It’s a criticism Dan Gilbert has heard more times than he can imagine. The chairman and founder of Quicken Loans, Gilbert is trying to revitalize downtown Detroit much as Plank hopes to transform Port Covington, the waterfront neighborhood he’s pouring millions into, and other parts of Baltimore.

News & Community

Tomorrowland

Port Covington will be like nothing Baltimore has ever seen. But at what cost?

The two have become friendly in recent years. Plank sat next to Gilbert for a quarter of an NBA Finals contest last year between the Cleveland Cavaliers, the team Gilbert owns, and the Golden State Warriors, who are led by Under Armour pitchman Stephen Curry. “[It was] the game we won, thank God,” Gilbert says.

While the tactics they are employing to boost their beleaguered cities may differ, the cores of the two men’s philosophies are very much the same.

“It’s using the leverage of your people and your capital to make the city a better place,” Gilbert says. “The secret of all of that, I think, is you actually are more profitable and a better company in the end if your people embrace it. I think he sees that for sure.”

Plank says he never thought of his philanthropic work as trying to buy a headline.

“Instead of taking the dollars I have to invest and sticking them in some real estate trust, I’m going to invest here in Baltimore,” he explains. “I want to give back. That hotel was something I saw falling in the water, and I watched several development plans happen with it over 10 years. I thought someone should actually do it. Things I can see and that our teammates here, my family, my friends, the people of Baltimore will be able to enjoy.”

Although his mother served in public office and worked in the state department during the Reagan administration, Plank has taken great pains to stay above the political fray. He has played golf with President Obama, and, according to CBS Sports, he donated $2,700 to Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign.

In February, during an interview on CNBC, he said this about newly elected President Trump: “To have such a pro-business president is something that’s a real asset for this country.”

As innocuous as he may have thought that sentiment sounded, negative reaction to it was swift. Curry, ballerina Misty Copeland, and actor Dwayne Johnson, three of Under Armour’s key endorsers, voiced their displeasure, and the company took out a full-page ad in the The Sun attempting to clarify his remarks.

“Aligning any brand with politics is usually a bad marriage,” says T. J. Brightman, president of A. Bright Idea, an advertising and public relations firm headquartered in Bel Air. “You’re always going to turn someone off. Why risk doing so with any consumer who already has an affinity to your brand, like Under Armour?”

Scott Plank, who was a high-ranking UA executive until he left the company in 2012, seems to bristle at the idea his brother’s comments were considered controversial.

“We’re not political people,” he says. “I don’t think he or anybody could have known just how sideways it would get with [his] statement.”

In August, Plank became the second CEO to quit the president’s now-defunct manufacturing job council following Trump’s controversial reaction to the Neo-Nazi and white supremacist demonstration in Charlottesville, VA.

“Being part of the council,” Brightman says, “there was a certain allure to having a seat at the table with the president, but I think that as we quickly found out, this current administration’s volatile nature that seems to change by the hour is not the place to be for any consumer brand. It’s a no-win situation—you’re bound to alienate someone.”

While questions about Trump were off limits during the interview for this story, Plank did speak to the general environment pervading the country these days.

“The cynicism in America right now is at an all-time high,” he says. “No matter what you do, I think people are going begin with what the negative of that could be, versus what’s the positive. Regardless of how pure your heart is, there will be a faction of people that will be questioning it.”

Coupled with Under Armour’s reduced sales projections for this year—in August it announced it would lay off 2 percent of its workforce, including about 140 jobs in Baltimore—2017 has been a humbling year for a man so used to winning. His net worth fell to $1.7 billion, down from $3 billion, and Under Armour's third-quarter earnings report revealed a 5-percent decrease, marking the company's first year-over-year revenue decline since it went public. At press time, the company’s stock was hovering around the low teens.

Still, Plank is unwavering in his belief in his company, his brand, and in himself.

“You live through those ups and downs,” Plank says. “We’ve had easier years, we’ve had better years at Under Armour, but I believe that ’17 is one of those years we’ll look back on and say it’s one of the most important we’ve ever had. For me, it means my primary focus is doubling down on culture. We can’t control what people say about us and how they feel about us, but we can control what we say about ourselves.”

Even as some analysts have jumped ship, others have remained bullish on Under Armour, in no small part because of its CEO.

“I know he’s had his challenges in the last year, but everybody always does,” Gilbert says. “I’m a big believer in Under Armour, because I’m a big believer in him. I tend to be a jockey guy more than a horse guy.”

rubbing mascot testudo's head for good luck with his teammates. courtesy of university of maryland archives.

Plank is a goal setter, and among his current ones is to eventually get eight hours of sleep a night. He used to be good with four, but now, in middle age, needs about five. To call him a workaholic misses the point; work is not something he does, it’s a part of who he is.

Tomorrow, he’s off to California for an event at Venice Beach celebrating Under Armour’s 15-year, $280 million deal with UCLA. ESPN reports that it’s the richest in college athletics. In the past four years, he’s flown more than 1 million miles.

“That means I’ve spent more than a month a year in the air,” he says. “But I love it. I don’t see it as work. Hopefully, intellectual curiosity is something that will always define me.”

When he lands in a new city, he’ll often explore it by going for a three- or four-mile run. He’s completed eight half-marathons, but his bucket list doesn’t include finishing a full one. (“Once your nipples start bleeding I don’t know how good of an idea that is.”) He works out with a trainer three times a week, and although he’s well below his playing weight of 237, he can still push around some iron.

Plank’s not the type to pause and consider his own mortality, or take stock of what he’s accomplished in life. He’s focused on the future, which leaves little time to smell the roses. His immense success has allowed him to buy some toys—his 530-acre Sagamore Farm, around which he enjoys four-wheeling, is a gorgeous one—and he’s still known to spend a summer day at the Starboard, a beach bar near his house on the Delaware shore.

But an ideal Saturday afternoon, Plank says, is one at home in Baltimore County with his wife (whom he’s known since high school), his 14-year-old son and 10-year-old daughter, a Terps game on the TV, and perhaps a glass of whiskey—Sagamore Rye, of course—nearby.

“I live next to the field where my son plays,” he says. “That was my dream: to be able to drive home, park my car, and walk over to this little berm and watch my son play football. It was perfect weather yesterday. To watch him be able to go out and throw the ball . . . it was a perfect day. He got hit, he got knocked down, but he kept getting back up.”

Wonder where the kid gets his resilience.