The opening of Harborplace sparked a waterfront renaissance beyond Baltimore’s wildest dreams. Four decades later, has the ship sailed for the twin pavilions?

Travel & Outdoors

The opening of Harborplace sparked a waterfront renaissance beyond Baltimore’s wildest dreams. Four decades later, has the ship sailed for the twin pavilions?

August 2021

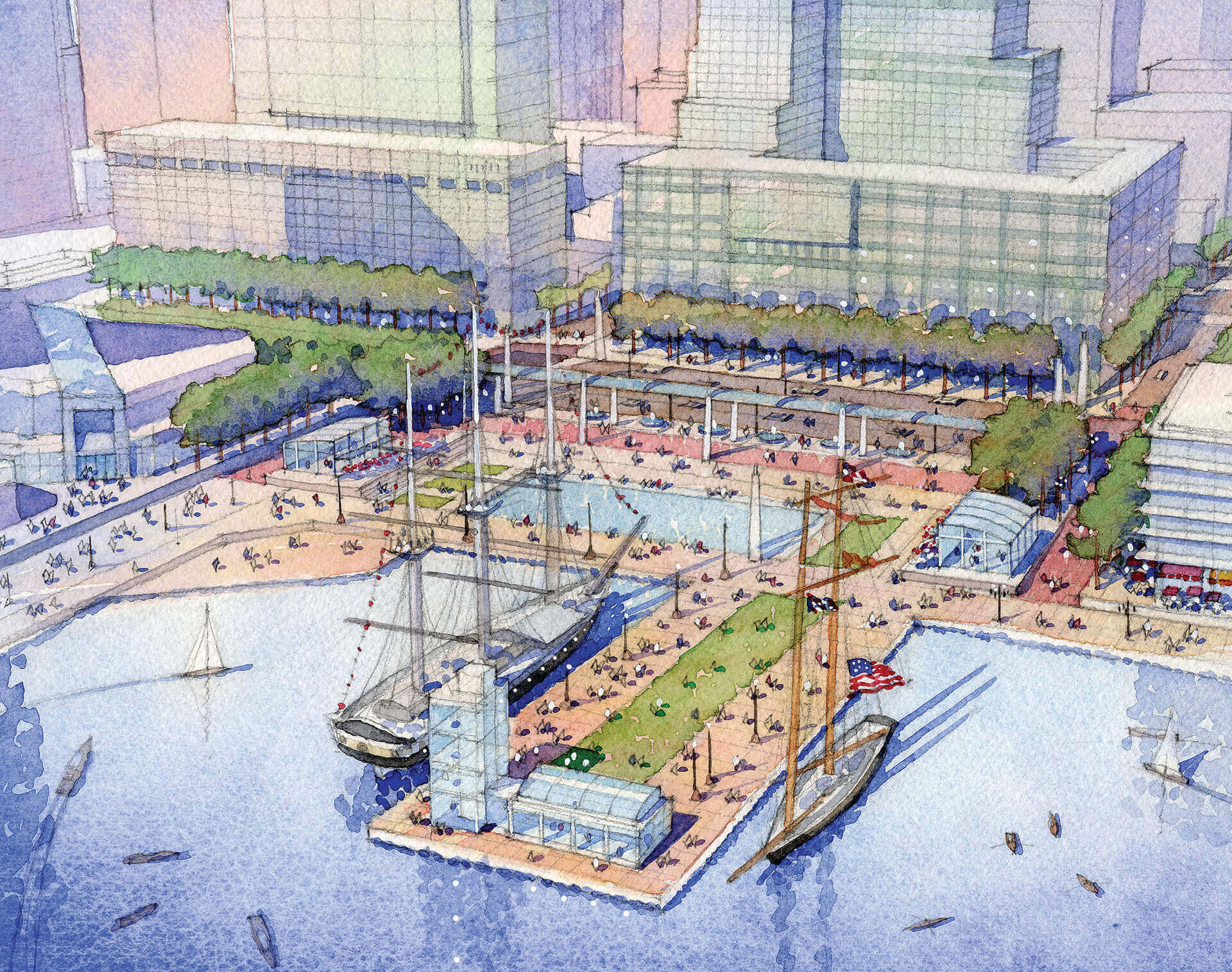

OPENING SPREAD: Watercolor rendering by Mahan Rykiel Associates and EE&K architects from the 2007 Pratt Street design competition. In the proposal, existing Harborplace pavilions have been torn down, Pratt Street has been turned into a two-way boulevard, and the Light Street spur removed to open accessibility to the Inner Harbor. ILLUSTRATION BY DARIUSH WATERCOLORS

NTHONY HAWKINS IS SITTING AT THE

amphitheater at Harborplace, between the landmark

pavilions he helped establish four decades ago. It’s a

beautiful, mid-morning day in late June. He takes

a deep breath. There’s hardly a cloud in the sky.

Also, hardly a soul in sight. “I’m a Baltimore boy. I’m

City College. Morgan. Hopkins,” Hawkins says with

emphasis. “My whole family on both sides is from

Baltimore. And this pisses me off,” the 76-year-old

continues with a frustrated nod toward the faded two-story green pavilions on either

side of him. “I don’t know how else to put it.” The last time Hawkins stepped inside

the twin pavilions at the intersection of Light and Pratt streets, the busiest in the

city, was two years ago. He refuses to again. “Everything is closed off. You have no

idea where you are going. I got so angry, it made me physically sick. I had to leave.”

NTHONY HAWKINS IS SITTING AT THE

amphitheater at Harborplace, between the landmark

pavilions he helped establish four decades ago. It’s a

beautiful, mid-morning day in late June. He takes

a deep breath. There’s hardly a cloud in the sky.

Also, hardly a soul in sight. “I’m a Baltimore boy. I’m

City College. Morgan. Hopkins,” Hawkins says with

emphasis. “My whole family on both sides is from

Baltimore. And this pisses me off,” the 76-year-old

continues with a frustrated nod toward the faded two-story green pavilions on either

side of him. “I don’t know how else to put it.” The last time Hawkins stepped inside

the twin pavilions at the intersection of Light and Pratt streets, the busiest in the

city, was two years ago. He refuses to again. “Everything is closed off. You have no

idea where you are going. I got so angry, it made me physically sick. I had to leave.”

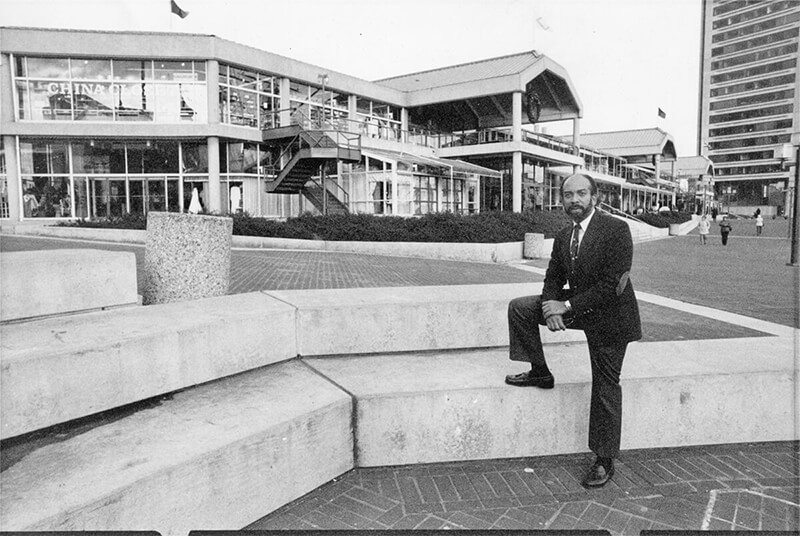

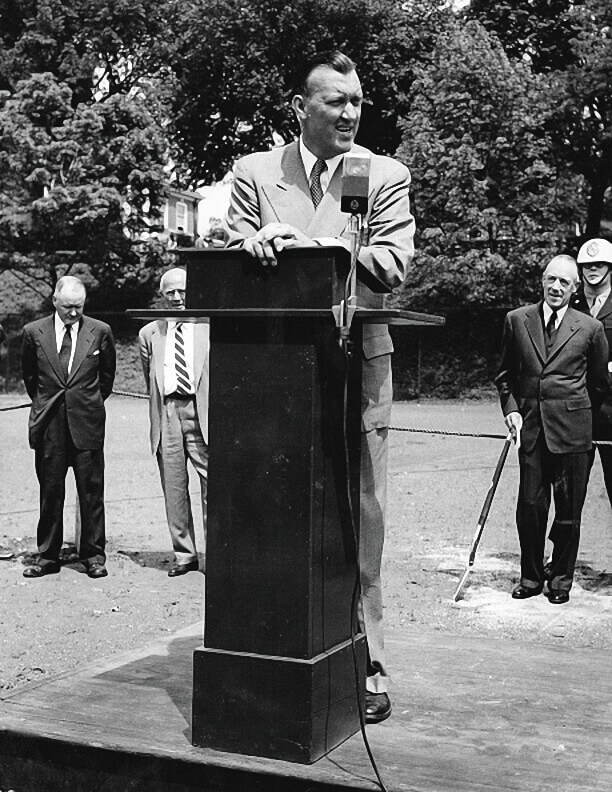

Press photo of Tony Hawkins at Harborplace (1983). Courtesy of Historic Images/Photography by Joe Giza

Harborplace is personal to Hawkins. He was the first general manager of the iconic retail and restaurant development, overseeing pavilion operations for 15 glorious years. He’d just built a home, in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, and was managing other Rouse Company properties in the region when Jim Rouse himself called to tell him that he needed him to return home. That was 1977. The tall ships had come to Baltimore for the country’s bicentennial the year before, drawing hundreds of thousands of visitors, including tens of thousands of Baltimoreans, to the waterfront. Rash Field was still hosting the city’s ethnic festivals and the very popular City Fair then. The “Sunny Sundays” concerts were pulling Baltimoreans to their harbor, too. But other than a promenade, and the Maryland Science Center and World Trade Center, which had both recently opened, little else in terms of built infrastructure existed at the time. Rouse, on the heels of his company’s successful Faneuil Hall Marketplace redevelopment in Boston, intended to change that. “He knew having someone who knew Baltimore to manage it was important,” Hawkins says. “Harborplace was supposed to be for the people who lived here, and it was,” Hawkins says. Ninety-percent of the businesses when it opened had local ties (including a busy comic-book store owned by Steve Geppi, this magazine’s owner). It was the belief of Rouse and former Mayor William Donald Schaefer, who famously cared little about the interests of non-Baltimoreans, that if locals came, tourists were more likely follow. But that was secondary. The point, Hawkins explains, is that Harborplace mattered to the people in charge. “At Rouse, we were hands-on, detailed-oriented. You have to be,” Hawkins says. “Tenants didn’t always like what we did. If you wanted to open a food business, you had to cook for 10 of us, including our food consultants.” The mayor, we know, operated the same way. “I’d get 5 a.m. calls from Schaefer about the trash outside Harborplace, and I didn’t even work for him. I’d tell him, ‘Our sanitation team arrives at 7. We’ll get it.’”

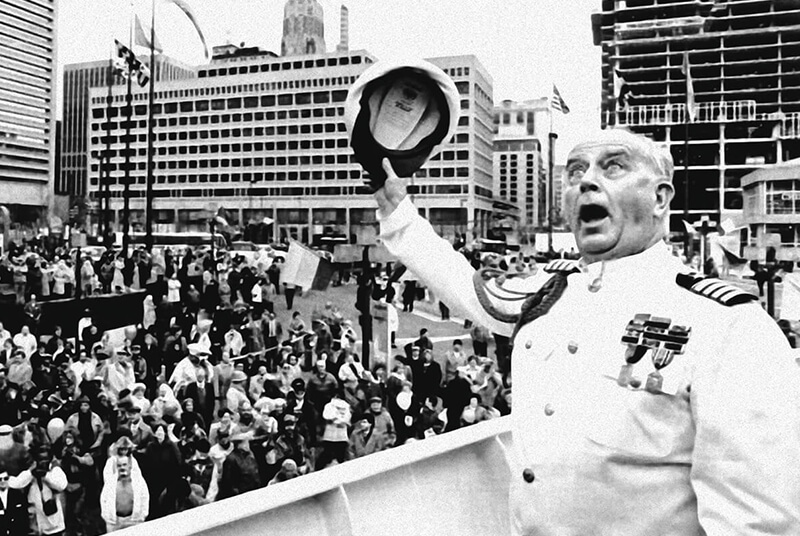

Former Mayor William Donald Schaefer: “Harborplace is of, by, and for the people of Baltimore.” COURTESY OF UPI

Not quite fully recovered from a long bout with COVID-19, Hawkins is at turns upset, discouraged, and nostalgic about Harborplace. It’s complicated, in other words. How many Baby Boomer and Gen-X Baltimoreans got their first job, went on their first date—or, like Hawkins, met their future spouse—at Harborplace? Tellingly, when his wife calls later and inquires about eating lunch out on this sunny day, Harborplace doesn’t even come up for consideration. Still, Hawkins is happy when former Raven Femi Ayanbadejo, a Harbor East condo neighbor, walks past with a companion and says hello. Seeing another acquaintance jogging toward him, Hawkins playfully jumps up and tugs on his friend’s oversized headphones. That’s the funny thing. There’s only a handful of people passing by over the course of an hour, but Hawkins seems to know many of them. Or they know him. It’s obvious city residents love and want to be outside near their waterfront. Whether the Harborplace pavilions are an attraction or an impediment is the question now. Someone else stops by and randomly mentions that the actress Jada Pinkett Smith and her friends used to come to Harborplace when she attended the School for the Arts. “Jada’s my neice,” Hawkins informs the man. “That’s how it used to be here. Smalltimore.”

Tony Hawkins today

at Harborplace. Photography by MIKE MORGAN

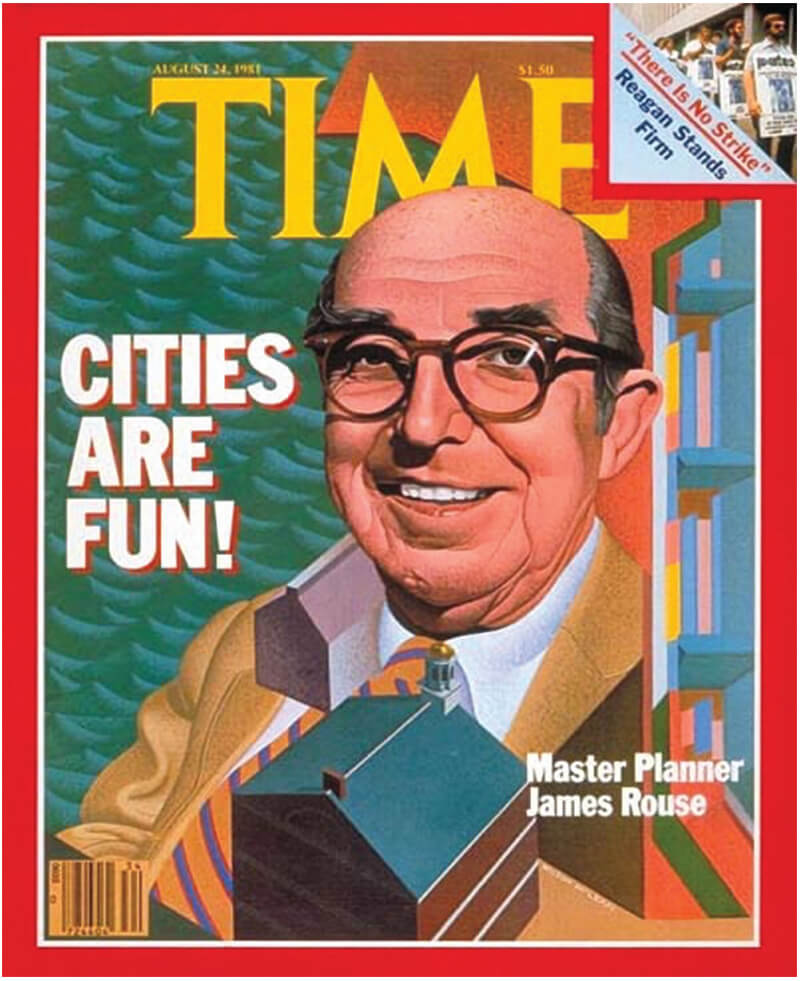

f you’re somewhat new to Baltimore and it’s not clear yet,

Harborplace and the Inner Harbor are often used interchangeably,

but they are not synonymous. Harborplace is

the 3-acre, privately owned, two-pavilion shopping and

eating area. The city only holds the ground lease. The Inner Harbor

stretches from the Rusty Scupper near the foot of Federal Hill, includes

the Harborplace pavilions, and sweeps around past the National

Aquarium to the Pier 6 outdoor convert venue. The Harborplace

pavilions opened in 1980, but not until after a contentious,

now forgotten, referendum battle. Many Baltimoreans didn’t want to

hand over their newly accessible waterfront to commercial development.

Others bought into the opportunity to change the city’s fortunes.

Ultimately, the “festival marketplace” mini-malls were celebrated

as the centerpiece of blue-collar Baltimore’s reinvention,

landing Rouse on the cover of Time—“Cities Are Fun!”—and putting a

sagging Baltimore back on the map. They helped draw 21 million

people to the Inner Harbor that first year and spark a waterfront renaissance

from Fort McHenry to Canton beyond the business community’s

wildest dreams, spinning off glittering Harbor East and,

more recently, Harbor Point, and a thousand projects, big and small,

everywhere in-between. Today, any native Baltimorean over 40

knows that Jim Rouse—with a building named after him at the nearby

American Visionary Art Museum—was the developer who built

Harborplace. But how many Baltimoreans know the name of the current

owners of Harborplace—Ashkenazy Acquisition Corp., a real-estate

investment firm based in New York? How many know the Harborplace

pavilions have been in receivership for more than two

years? Or that, with a vacancy rate that now tops 60 percent, the future

of Baltimore’s “centerpiece” is in the hands of court-appointed

receiver Ian Lagowitz, the owner of a small Montclair, New Jersey-based

financial group and associate men’s golf coach at Seton Hall

University? It’s Lagowitz’s job to figure out what is in the best financial

interests of his clients—Deutsche Bank and UBS-Barclays, holders

of Ashkenazy’s mortgage on Harborplace—not Baltimore City.

f you’re somewhat new to Baltimore and it’s not clear yet,

Harborplace and the Inner Harbor are often used interchangeably,

but they are not synonymous. Harborplace is

the 3-acre, privately owned, two-pavilion shopping and

eating area. The city only holds the ground lease. The Inner Harbor

stretches from the Rusty Scupper near the foot of Federal Hill, includes

the Harborplace pavilions, and sweeps around past the National

Aquarium to the Pier 6 outdoor convert venue. The Harborplace

pavilions opened in 1980, but not until after a contentious,

now forgotten, referendum battle. Many Baltimoreans didn’t want to

hand over their newly accessible waterfront to commercial development.

Others bought into the opportunity to change the city’s fortunes.

Ultimately, the “festival marketplace” mini-malls were celebrated

as the centerpiece of blue-collar Baltimore’s reinvention,

landing Rouse on the cover of Time—“Cities Are Fun!”—and putting a

sagging Baltimore back on the map. They helped draw 21 million

people to the Inner Harbor that first year and spark a waterfront renaissance

from Fort McHenry to Canton beyond the business community’s

wildest dreams, spinning off glittering Harbor East and,

more recently, Harbor Point, and a thousand projects, big and small,

everywhere in-between. Today, any native Baltimorean over 40

knows that Jim Rouse—with a building named after him at the nearby

American Visionary Art Museum—was the developer who built

Harborplace. But how many Baltimoreans know the name of the current

owners of Harborplace—Ashkenazy Acquisition Corp., a real-estate

investment firm based in New York? How many know the Harborplace

pavilions have been in receivership for more than two

years? Or that, with a vacancy rate that now tops 60 percent, the future

of Baltimore’s “centerpiece” is in the hands of court-appointed

receiver Ian Lagowitz, the owner of a small Montclair, New Jersey-based

financial group and associate men’s golf coach at Seton Hall

University? It’s Lagowitz’s job to figure out what is in the best financial

interests of his clients—Deutsche Bank and UBS-Barclays, holders

of Ashkenazy’s mortgage on Harborplace—not Baltimore City.

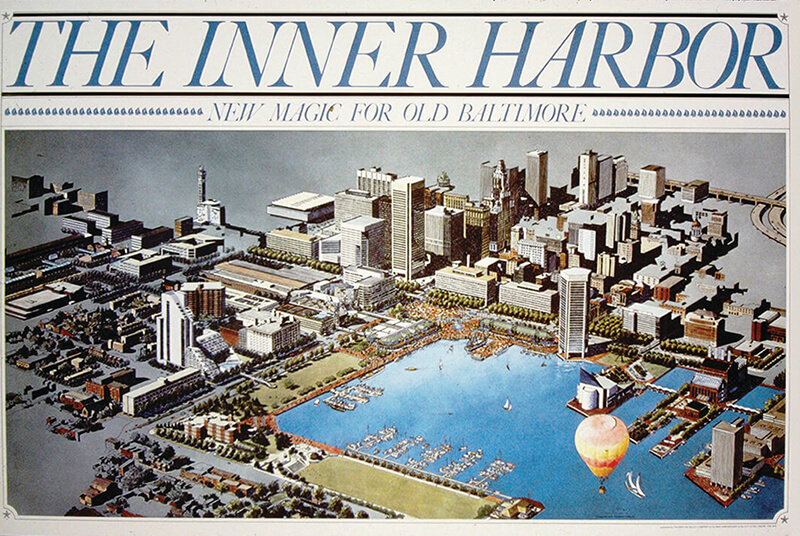

Early poster promoting the Inner Harbor and Harborplace.

Across the board, elected leaders and city officials, including Baltimore Development Corporation President Colin Tarbert—the city’s point man on the process—say they have virtually no input regarding the receivership. (Councilman Eric Costello, whose district includes the Inner Harbor, says he and former Mayor Jack Young were out of town on business when they first learned Harborplace was headed to receivership.) They all say their hands are tied regarding the likely sale of Harborplace given that Ashkenazy’s lease was extended to 2087 when they bought the pavilions in 2012. And you thought Chris Davis’ contract was an anchor around the neck of the Orioles.

The best hope, according to city officials, is a local development company steps up soon to purchase Harborplace. At that point, the new owners will most certainly make grand promises like General Growth Properties did when they bought it from the Rouse Company in 2004, and like Ashkenazy did when they bought it from General Growth in 2012. Along with city officials, they’ll talk up major renovations and a new theme. They’ll tout plans to recruit an exciting and diverse mix of Baltimore and Maryland retailers and restaurants, maybe a brew pub, promising, fingers crossed, it will be a game-changer.

A new group of tenants will never be the solution. “Shouldn’t truly great urban places strive for more permanence?”

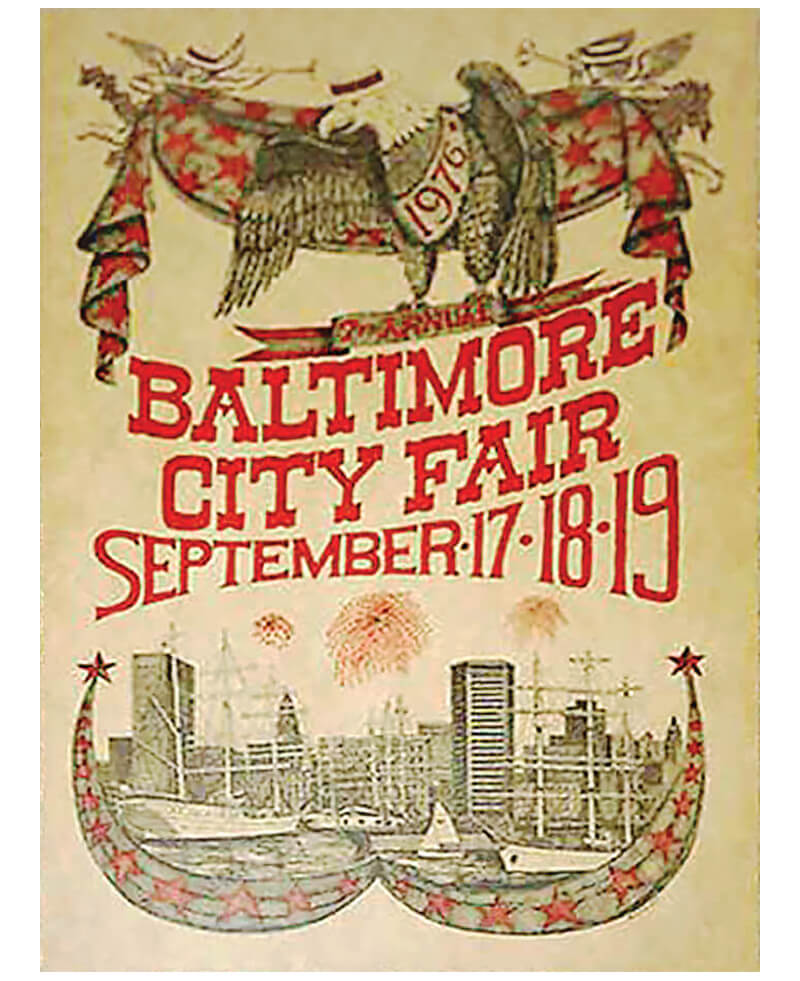

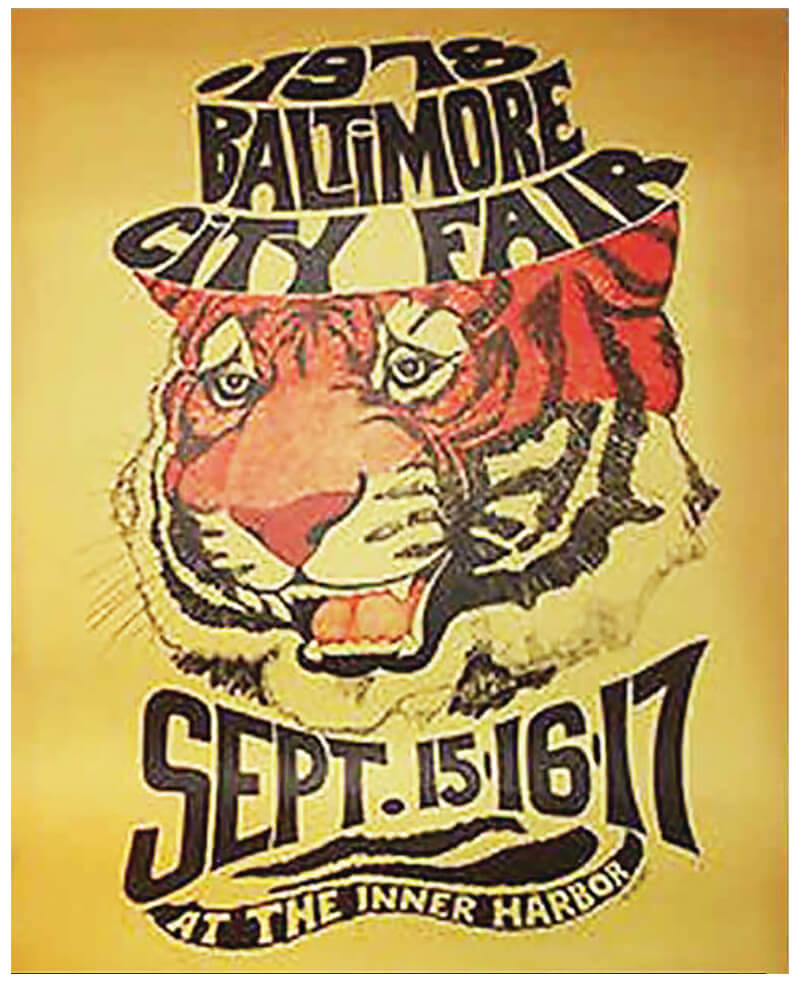

Baltimore City Fair

posters from the

1970s; Time magazine

cover featuring James

Rouse.

n reality, the ship has sailed for the twin pavilions.

It’s past time to demolish at least one,

ideally both, say leading urban planners in the

city. It’s actually one thing both former Mayor

Jack Young and new Mayor Brandon Scott have

previously agreed on, too—although Young later somewhat

backpedaled his remarks. The truth is, outside of

Baltimore and Boston, the “festival marketplace” boom,

the one-time silver bullet for decaying downtowns, failed across

the country. Eventually, inevitably, it began to fail here, too, the

result of changing retail habits, the death of indoor malls, and

the demand for more urban green space. A new group of tenants

will never be the solution, says Klaus Philipsen, the longtime

past co-chair of the Urban Design Committee of the Baltimore

chapter of the American Institute of Architects, who describes

Harborplace as “rotting.” Besides, as he asked almost a dozen

years ago: Should city plazas really have to rebrand themselves

constantly? “Shouldn’t truly great urban places,” Philipsen says,

“strive for more permanence?”

n reality, the ship has sailed for the twin pavilions.

It’s past time to demolish at least one,

ideally both, say leading urban planners in the

city. It’s actually one thing both former Mayor

Jack Young and new Mayor Brandon Scott have

previously agreed on, too—although Young later somewhat

backpedaled his remarks. The truth is, outside of

Baltimore and Boston, the “festival marketplace” boom,

the one-time silver bullet for decaying downtowns, failed across

the country. Eventually, inevitably, it began to fail here, too, the

result of changing retail habits, the death of indoor malls, and

the demand for more urban green space. A new group of tenants

will never be the solution, says Klaus Philipsen, the longtime

past co-chair of the Urban Design Committee of the Baltimore

chapter of the American Institute of Architects, who describes

Harborplace as “rotting.” Besides, as he asked almost a dozen

years ago: Should city plazas really have to rebrand themselves

constantly? “Shouldn’t truly great urban places,” Philipsen says,

“strive for more permanence?”

“Envision with me, too, a new Inner Harbor area, where the imagination of man can take advantage of a rare gift of Nature to produce an enthralling panorama of office buildings, parks, high-rise apartments and marinas. In this we have a very special opportunity, for few other cities in the world have been blessed, as has ours, with such a potentially beautiful harbor area within the very heart of downtown. Too visionary, this? Too dream-like.”

—Mayor Theodore McKeldin, at his War Memorial Building inaugural address after returning from the governor’s mansion in Annapolis to serve a second term on May 21, 1963.

Watercolor from the

Pratt Street Design

Competition.

illiam Donald Schaefer, rightly so, gets the most credit

for revitalizing the Inner Harbor. But the first mayor to

see its potential was Theodore McKeldin. Inspired by

McKeldin’s vision, optimism, and can-do spirit, Baltimore

voters approved a city bond for an Inner Harbor Master Plan

in 1964. Cobbling bond money with federal grants, the city began

acquiring vacant warehouses, clearing out old piers, and building

a new bulkhead along the waterline. The harbor had to be dredged

and the toxic industrial sediments hauled away. Hundreds of properties

were acquired and hundreds of businesses were relocated.

illiam Donald Schaefer, rightly so, gets the most credit

for revitalizing the Inner Harbor. But the first mayor to

see its potential was Theodore McKeldin. Inspired by

McKeldin’s vision, optimism, and can-do spirit, Baltimore

voters approved a city bond for an Inner Harbor Master Plan

in 1964. Cobbling bond money with federal grants, the city began

acquiring vacant warehouses, clearing out old piers, and building

a new bulkhead along the waterline. The harbor had to be dredged

and the toxic industrial sediments hauled away. Hundreds of properties

were acquired and hundreds of businesses were relocated.

Theodore McKeldin at a groundbreaking ceremony for Johns Hopkins in 1953.

Tom Todd, one of the architects hired by the city to create a master plan that mapped the attraction’s “problems and opportunities,” anticipated a lot of the major issues that impede progress today at the Inner Harbor, Harborplace, the equally bleak Gallery mall, vacant Pratt Street storefronts, and desolate McKeldin Plaza. Most notably: the high-volume, urban highway that is Pratt Street and problematic Light Street spur, which separates the now grassy knoll of McKeldin Plaza from the Inner Harbor with five lanes of traffic. When the 1964 master plan was created, the proposed east-west highway was still expected to meet up with I-83 over the Inner Harbor between Federal Hill and what is now Harbor East. The east-west highway famously got defeated after organized citizen opposition, led in part by the efforts of a Fells Point community activist named Barbara Mikulski. The downside is that the Inner Harbor got stuck with its highway remnants: Pratt and Light streets and Key Highway. For at least 25 years, the very uniqueness of the Inner Harbor and Harborplace—it pays to be first—simply outshone any broader urban design flaws. And malls and mini-malls, like the Harborplace pavilions, were the social gathering places of the era. It was electric. The downtown business crowd and City Hallers came for lunch, Baltimoreans came to shop, and tourists didn’t just follow, they flocked.

Kaliope Parthemos, who later became Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake’s chief of staff, worked at Harborplace from 1986-1994, all through high school and college. “In those days, and I know it sounds funny, but it was the ‘cool’ place to work,” Parthemos says, noting The Fudgery, the singing fudge shop that opened in 1985 in Harborplace, launched the Top 40 careers of Baltimore R&B group Dru Hill and lead singer Mark “Sisqó” Andrews in the ’90s. “Break dancers and aspiring rappers used to come down at night and perform out at the amphitheater. Tupac used to come down, too, and rap. People came from every neighborhood.” Both future Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake and Downtown Partnership President Shelonda Stokes got their first jobs at Harborplace. Stokes was on the clean-up crew. “I went to Poly,” she says, “and couldn’t wait to go down there after school.”

Shortly after Harborplace was sold from General Growth Properties to Ashkenazy, Parthemos became the city’s deputy mayor of economic and neighborhood development. Ashkenazy, she notes, did invest in renovations, but failed to attract and keep local businesses, instead counting on national brands such as Urban Outfitters, Banana Republic, Johnny Rockets, and Five Guys, all of which, along with a litany of others, decamped prior to the pandemic. Several chains survive: Bubba Gump Shrimp Co., Pizzeria Uno, The Cheesecake Factory, Hooters, H&M. “Baltimore is unique and has its own culture,” she says. “A gathering place needs to feel like Baltimore.”

"Break Dancers and aspiring rappers used to come down at night and perform out at the amphitheater. Tupac used to come down, too, and rap. People came from every neighborhood."

The

Light Street Pavilion

at Harborplace, 1985. COURTESY OF RHODE ISLAND COLLEGE, JAMES P. ADAMS LIBRARY DIGITAL COMMONS

t is easy to forget, given the blight and vacancy

rates at Harborplace, that more people live and

work downtown than ever before. But rather than

attract those urban dwellers, the desolate pavilions

stand as one of two massive concrete barriers between

those residents—and all Baltimoreans, for that matter—and

their waterfront. The high-volume, high-speed traffic that

gets funneled from I-95 alongside the pavilions—via the

Light Street spur and Pratt Street—is the other, of course.

“Nothing should ever be placed between citizens and the water,”

says Baltimore City state delegate Robbyn Lewis. “I

learned that going to school in Chicago as a girl. I remember looking out the window, wondering why there would be a road [the

Lake Shore Drive expressway] between Lake Michigan and the city

parks on the other side, like Grant Park, the one where Obama gave

his first acceptance speech.” As for the pavilions, Lewis says, “If

they sank into the harbor,” it’d be fine with her.

t is easy to forget, given the blight and vacancy

rates at Harborplace, that more people live and

work downtown than ever before. But rather than

attract those urban dwellers, the desolate pavilions

stand as one of two massive concrete barriers between

those residents—and all Baltimoreans, for that matter—and

their waterfront. The high-volume, high-speed traffic that

gets funneled from I-95 alongside the pavilions—via the

Light Street spur and Pratt Street—is the other, of course.

“Nothing should ever be placed between citizens and the water,”

says Baltimore City state delegate Robbyn Lewis. “I

learned that going to school in Chicago as a girl. I remember looking out the window, wondering why there would be a road [the

Lake Shore Drive expressway] between Lake Michigan and the city

parks on the other side, like Grant Park, the one where Obama gave

his first acceptance speech.” As for the pavilions, Lewis says, “If

they sank into the harbor,” it’d be fine with her.

A number of Baltimore architects and urban planners have recognized this for some time. In 2007, as part of the Pratt Street redesign competition hosted by the Downtown Partnership, the concept from Mahan Rykiel Associates and EE&K removed the Pratt Street pavilion and Light Street spur, turning Pratt Street into a two-way boulevard. In the place of the Light Street spur, their plan called for a new, tree-filled McKeldin Plaza extended into the Inner Harbor fold. (The subsequent demolition of the brutalist McKeldin Fountain by the city in 2017, in fact, makes this more possible.) Today, if you go stand at the far corner of Charles and Pratt streets and look back toward the Inner Harbor, it’s easy to envision how removing the spur and pavilions and returning the intersection to a basic grid opens up the potential in the area for a huge central park in the heart of downtown.

Harborplace opened July 2, 1980.

“Every planner was building one-way roads like Pratt Street to prevent gridlock in the 1960s,” says Scott Rykiel, co-founder of Mahan Rykiel Associates, who led his firm’s team in the 2007 Pratt Street design competition. “But the other problem is the Pratt Street pavilion blocks access and views of the waterfront. The retail in the Pratt Street pavilion could easily be replaced along the north side of Pratt Street. There is also a dearth of open space, however, in Baltimore,” Rykiel continues, “and there are few places to build new park squares.” As has been well documented, Baltimore desperately needs tree canopy. Rykiel, who has Polish roots in Fells Point and lived there as a graduate student in the late ’70s and early ’80s, adds that by making the nearly 3-acre McKeldin Plaza the outside edge of the Inner Harbor, it would create a large-parcel, two-sided entrance to the waterfront. “Parks are economic generators, which I don’t think we talk about enough,” Rykiel says. The reclamation of Patterson Park is one example. “The pandemic [with state park attendance breaking records] may change that.” Overwhelmingly, the number one reason Baltimoreans visit the Inner Harbor is simply to walk and view the water, according to surveys.

The removal of the Light Street spur was also a part of the city's 2014 Inner Harbor 2.0 master plan, managed by the Waterfront Partnership. Ultimately, the aim of a Light Street spur and Pratt Street redesign is to encourage pedestrian, bicycle, and scooter traffic between Pratt and the Inner Harbor, but also up Charles Street, which has never happened—not even in Harborplace’s heyday.

A major issue, as Philipsen highlights, is that the twin pavilions have always blocked the view of the water and presented their less than attractive backsides to the rest of downtown. This less than welcoming position seems even more critical given Harborplace’s decline. But any attempt to alleviate the issue runs into problems, like the need for dumpsters and delivery docks. Ideally, he says, both pavilions should go. “The urban design of Harborplace and ‘festival marketplace’ concept is obsolete,” Philipsen says. “At minimum, everything could fit into one of them.”

The city, of course, would have to buy the pavilions from Ashkenazy in order to do anything like that. With Harborplace in receivership and the opportunity COVID presents for a reset, Philipsen says now is the time to act. Potentially, federal recovery money can be put toward demolition and transformation of property. General Growth paid $138 million for Harborplace. Ashkenazy paid $98.5 million, meaning the city could conceivably buy it out of receivership and hand the land back to taxpayers for significantly less than half ($80 million) of the aforementioned Chris Davis deal. Several city officials, including Colin Tarbert, the president of the Baltimore Development Corporation, and Don Fry of the Greater Baltimore Committee, said acquiring pavilions through condemnation or eminent domain has been discussed, but neither avenue is under consideration. “Too costly, and it takes too much time— years,” says Tarbert. “We’re waiting to see what happens with receivership. We’re just not in control of the situation.”

"The Focus is on Baltimore families to gather here at the inner harbor, and health and wellness."

Rendering of Rash Field, which is

undergoing a nearly $17-million development,

with the first phases to be completed this fall. Gensler/Mahan Rykiel, Courtesy of Waterfront Partnership

one of this is to say there aren’t

remarkable things happening at

the Inner Harbor. The first phase

of a nearly $17-million redevelopment

of Rash Field, the first

large-scale public space redevelopment at

the Inner Harbor in decades, should be completed

this fall. The nearly 8-acre redesign

will continue to host volleyball on sand and

add two playgrounds and a year-round

skatepark. It will also boast a hands-on nature

walk and rain garden, and a modern

café. “The focus is on Baltimore families to gather here at the

Inner Harbor, and health and wellness,” says Laurie Schwartz,

president of the Waterfront Partnership, encouragingly. (One

more Smalltimore note: Schwartz’s husband, Al Copp, who

passed several years ago, was one of the city officials behind

the Inner Harbor development.)

one of this is to say there aren’t

remarkable things happening at

the Inner Harbor. The first phase

of a nearly $17-million redevelopment

of Rash Field, the first

large-scale public space redevelopment at

the Inner Harbor in decades, should be completed

this fall. The nearly 8-acre redesign

will continue to host volleyball on sand and

add two playgrounds and a year-round

skatepark. It will also boast a hands-on nature

walk and rain garden, and a modern

café. “The focus is on Baltimore families to gather here at the

Inner Harbor, and health and wellness,” says Laurie Schwartz,

president of the Waterfront Partnership, encouragingly. (One

more Smalltimore note: Schwartz’s husband, Al Copp, who

passed several years ago, was one of the city officials behind

the Inner Harbor development.)

Laurie Schwartz, president of the Waterfront Partnership, stands in front of Rash Field. Photography by Mike Morgan.

Standing next to Rash Field as jackhammers pile away, Schwartz gestures across to West Shore Park, a previous Inner Harbor addition and ongoing success story. Situated on the opposite side of the Maryland Science Center, the 3-acre-plus green space features a cooling fountain for kids to jump around in and continues to draw families. Similarly, the music-themed Pierce’s Park on the eastern edge of the Inner Harbor is another fairly recent and ongoing attraction.

Other good, and slightly incredible, news, is that neither the National Aquarium nor the Science Center have lost a step all these decades later. The aquarium draws 1.2-1.3 million visitors a year in a normal year, and its numbers are bouncing back after shutting down for 100 days in 2020. The Science Center draws roughly 500,000, and the family-oriented project at Rash Field should only make it more of a destination. Add in the Baltimore Museum of Industry, AVAM, Fort McHenry, and the Reginald F. Lewis Museum, to name a few, and there is no shortage of attractions.

The problem, however, remains too much concrete, too many vacant storefronts, and too much traffic to maintain an authentic sense of place at Harborplace. “None of the great city centers are dominated by traffic,” says Fred Kent of the Project for Public Spaces. “By demolishing the pavilions, you open things up and offer the potential for a more natural interaction with the water that’s not all concrete. Light, quick interactions with small mom-and-pop businesses are essential. People want to go somewhere they can meet the owner.

“The biggest thing,” continues Kent, who is very familiar with Baltimore, “is you don’t want the process to be top-down driven, which is what’s typical. Architects design an award-winning building or landscape, the city officials start planning activities around it, and then everyone hopes people show up. No. It should be inverted. Open things up, keep its potential uses as wide as possible, see the kind of things people start using the space for—and then design around that, if need be.” Sandlot, the pop-up beach over in Harbor Point that has become a destination for volleyball, drinks, and sunset selfies, is a perfect example.

The Harborplace area could once again be “an absolutely phenomenal parcel of land,” Kent says, “and the central gathering place for the city, which Baltimore lacks right now.”

The focus, Kent, Philipsen, and others say, should be on activities and programming. They suggest bringing back things like ice-cream making, a fishmonger, and maybe moving the farmers’ market under the Jones Falls Expressway to the greenspace created by removing a pavilion or the open-air McKeldin Plaza.

“The waterfront should be like the main square for all the city,” Philipsen says. “That should be its identity.”